Queer Genealogies Across the Color Line and Into Children's Literature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EPISODE 147: Loving Math with Read-Alouds

® EPISODE 147: Loving Math with Read-Alouds Kortney: 00:00 The scientist Margaret Wertheim says, "Mathematics, in a sense, is logic let loose in the field of the imagination." Sarah: 00:19 You're listening to the Read-Aloud Revival Podcast. This is the podcast that helps you make meaningful and lasting connections with your kids through books. Sarah: 00:37 Hello, hello, Sarah Mackenzie here. Happy to have you with us for episode 147 of the podcast. I am here today with the Read-Aloud Revival team, that includes our Community Director Kortney Garrison and our Podcast Manager, Kara Anderson. We're here today to talk about math. Sarah: 00:58 Now don't shut off the podcast. I know you want to. On the Read-Aloud Revival, we're going to talk about math? Yes, we are. We're going to do it in the best way we know how. We're going to talk about stories to share with our kids that are mathematically related, stories that deepen our kids' appreciation for math or maybe even deepen our own, and some of us could use some of that. Isn't that right? Sarah: 01:19 But also books that help them understand tricky mathematical concepts and teach math in a really delightful way. We have a whole brand new book list hot off the presses. If you are on the email list, you already got it. If you're not on the email list, you can go grab it. The book list is at readaloudrevival.com/147. -

Where Do Black Children Belong, the Politics of Race Matching in Adoption

University of Pennsylvania Law Review FOUNDED 1852 Formerly American Law Register VOL. 139 MAY 1991 No. 5 ARTICLES WHERE DO BLACK CHILDREN BELONG? THE POLITICS OF RACE MATCHING IN ADOPTION ELIZABETH BARTHOLETt TABLE OF CONTENTS I. EARLY FRAGMENTS FROM ONE TRANSRACIAL ADOPTION STORY ............................. 1164 t Professor of Law, Harvard Law School. I am grateful to the many family members, friends, and colleagues who gave generously of their time reading and commenting on previous drafts. Special thanks go to: Anita Allen, Laura Armand, Robert Bennett, David Chambers, Nancy Dowd, Derek DuBois, Gerald Frug, MaryJoe FrugJoan Hollinger, Michael Meltsner, Frank Michelman, Martha Minow, Robert Mnookin, Alan Stone, Deborah Stone, Gerald Torres, Harriet Trop, and Ciba Vaughan. I am also indebted to those professionals and scholars in the adoption field whose names are listed infra note 50, who helped illuminate for me the nature of current racial matching policies and their impact on children. An abbreviated version of this Article will appear in a chapter of a forthcoming book by the author on adoption, reproductive technology, and surrogacy, with the working title of ChildrenBy Choice, to be published by Houghton Mifflin. (1163) 1164 UNIVERSITY OFPENNSYLVANIA LAW REVIEW [Vol. 139:1163 II. THE HISTORY ............................... 1174 III. CURRENT RACIAL MATCHING POLICIES ............. 1183 A. A Picture of the Matching Process at Work .......... 1186 B. The Proverbial Tip of the Iceberg-Of Written Rules and Documented Cases ....................... 1189 1. Laws, Regulations, and Policy Guidelines Mandating Consideration of Race in the Placement Decision ..................... 1189 2. Cases Documenting the Removal of Black Children from White Foster Families to Prevent Transracial Adoption ............. -

Transracial Adoption and Gentrification: an Essay on Race, Power, Family, and Community Twila L

Boston College Third World Law Journal Volume 26 Issue 1 Black Children and Their Families in the 21st Article 4 Century: Surviving the American Nightmare or Living the American Dream? 1-1-2006 Transracial Adoption and Gentrification: An Essay on Race, Power, Family, and Community Twila L. Perry [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/twlj Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Family Law Commons, and the Land Use Planning Commons Recommended Citation Twila L. Perry, Transracial Adoption and Gentrification: An Essay on Race, Power, Family, and Community, 26 B.C. Third World L.J. 25 (2006), http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/twlj/vol26/ iss1/4 This Symposium Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Boston College Third World Law Journal by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TRANSRACIAL ADOPTION AND GENTRIFICATION: AN ESSAY ON RACE, POWER, FAMILY AND COMMUNITY Twila L. Perry* Abstract: In this article, Professor Perry ªnds common ground between the two seemingly disparate contexts of transracial adoption and gentriª- cation. Professor Perry argues that both transracial adoption and gen- triªcation represent contexts in which, in the future, there may be increasing competition for limited resources. In the former case, the limited resource is the healthy Black newborn. In the later, it is desirable, affordable housing in the centers of our cities. After explaining how a competition between Blacks and whites over Black newborns could arise, Professor Perry argues that in any such competition, Blacks will increas- ingly ªnd themselves at a disadvantage stemming from the consequences of institutionalized racism. -

Trans-Racial Foster Care and Adoption: Issues and Realities (Pdf)

2013 massachusetts family impact seminar Trans-Racial Foster Care and Adoption: Issues and Realities by fern Johnson, ph.D., with the assistance of stacie Mickelson and Mariana lopez Davila Trans-racial adoption (TRA), the adoption of children of one race by parents of another, has grown rapidly since the middle of the 20th century, but this adoption option remains controversial [1]. In the state system through which children move from foster care to adoption, there are more white parents who want to adopt than there are white children waiting for homes, and children of color are less likely than white children to be placed in a permanent home. Legislative efforts to amend these discrepancies by promoting TRA have not significantly improved placement statistics. This report describes the positions of advocates on both sides of the TRA debate and explores methods for increasing the number of permanent placements of children into loving stable homes. DeMograpHiC anD proCESS perspeCtiVes on FOSTER Care anD aDoption who are the children waiting for homes and families? massachusetts court data for 2008 indicate that 2,272 children were adopted in the state, with approximately one-third (712) of these adoptions occurring through the public agency system [2]. in fy 2011, the number of public agency adoptions in the state was 724 [3]. in 2011, more than 7,000 children under the age of 18 were in the adoption placement system in massachusetts; 5,700 were in foster care and the rest in other arrangements, including group homes [4]. adoption was a goal for 32% (2,368) of these children. -

The Multiethnic Placement Act Minorities in Foster Care and Adoption

U.S. COMMISSION ON CIVIL RIGHTS The Multiethnic Placement Act Minorities in Foster Care and Adoption BRIEFING REPORT U.S. COMMISSION ON CIVIL RIGHTS Washington, DC 20425 Visit us on the Web: www.usccr.gov J U LY 2 0 1 0 U . S . Commission on Civil Rights ME M BE rs OF thE Commission The U.S. Commission on Civil Rights is an independent, Gerald A. Reynolds, Chairman bipartisan agency established by Congress in 1957. It is Abigail Thernstrom, Vice Chair directed to: Todd Gaziano • Investigate complaints alleging that citizens are being Gail Heriot deprived of their right to vote by reason of their race, color, Peter N. Kirsanow religion, sex, age, disability, or national origin, or by reason Arlan D. Melendez of fraudulent practices. Ashley L. Taylor, Jr. • Study and collect information relating to discrimination or a denial of equal protection of the laws under the Constitution Michael Yaki because of race, color, religion, sex, age, disability, or national origin, or in the administration of justice. Martin Dannenfelser, Staff Director • Appraise federal laws and policies with respect to discrimination or denial of equal protection of the laws U.S. Commission on Civil Rights because of race, color, religion, sex, age, disability, or 624 Ninth Street, NW national origin, or in the administration of justice. Washington, DC 20425 • Serve as a national clearinghouse for information in respect to discrimination or denial of equal protection of the laws (202) 376-8128 voice because of race, color, religion, sex, age, disability, or (202) 376-8116 TTY national origin. www.usccr.gov • Submit reports, findings, and recommendations to the President and Congress. -

The Return of the 1950S Nuclear Family in Films of the 1980S

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2011 The Return of the 1950s Nuclear Family in Films of the 1980s Chris Steve Maltezos University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons, and the Film and Media Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Maltezos, Chris Steve, "The Return of the 1950s Nuclear Family in Films of the 1980s" (2011). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/3230 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Return of the 1950s Nuclear Family in Films of the 1980s by Chris Maltezos A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Liberal Arts Department of Humanities College Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Daniel Belgrad, Ph.D. Elizabeth Bell, Ph.D. Margit Grieb, Ph.D. Date of Approval: March 4, 2011 Keywords: Intergenerational Relationships, Father Figure, insular sphere, mother, single-parent household Copyright © 2011, Chris Maltezos Dedication Much thanks to all my family and friends who supported me through the creative process. I appreciate your good wishes and continued love. I couldn’t have done this without any of you! Acknowledgements I’d like to first and foremost would like to thank my thesis advisor Dr. -

Bedtime Story by Anita Amin

Name: _________________________________ Rosie’s Bedtime Story By Anita Amin Rosie loved bedtime. Her dad always told her stories. Sometimes, he told fairy tales. Sometimes, he told animal stories. And sometimes, he told sports stories. Rosie couldn’t wait to hear Dad’s next story. But that night, Mom tucked Rosie into bed instead. “Dad is sick,” Mom told Rosie. “But I can tell you a story if you want me to.” So Mom told Rosie a story. But to Rosie, it wasn’t the same. She felt sad. She didn’t want Dad to be sick, and she missed story time with Dad. She thought maybe Dad missed story time, too. This gave her an idea. Rosie hopped out of bed. She went to Dad’s room. She knocked on his door. “Come in,” Dad said. When Rosie opened the door, Dad smiled weakly. “I’m sorry. I’m going to miss story time tonight.” Rosie sat on Dad’s bed. “No you won’t. I’m going to tell you a story.” So Rosie told Dad a story about a castle, a dragon, and a princess. Dad loved the story and he fell asleep with a smile on his face. “Get well quickly, Dad,” Rosie whispered. Super Teacher Worksheets - www.superteacherworksheets.com Name: ___________________________________ Rosie’s Bedtime Story By Anita Amin 1. Complete the graphic organizer. 3 Types of Stories that Dad Tells Rosie 2. Why didn’t Rosie’s dad tuck her into bed? ________________________________________________________________ 3. What type of story did Rosie tell her dad? a. a true story b. -

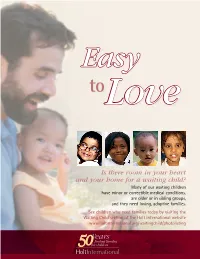

Is There Room in Your Heart and Your Home for a Waiting Child?

Easy toLove Is there room in your heart and your home for a waiting child? Many of our waiting children have minor or correctible medical conditions, are older or in sibling groups, and they need loving, adoptive families. See children who need families today by visiting the Waiting Child section of the Holt International website www.holtinternational.org/waitingchild/photolisting finding families for children Dear Readers Christina* greeted me a few years ago at the home of her foster family in Romania. She was 12 years old, with dark eyes, and dark hair pulled back into a SUMMER 2006 VOL. 48 NO. 3 HOLT INTERNATIONAL CHILDREN’S SERVICES ponytail that framed her pretty face. I was surprised by how normal and healthy P.O. Box 2880 (1195 City View) Eugene, OR 97402 she looked. Ph: 541/687.2202 Fax: 541/683.6175 OUR MISSION I expected her to look, well… sick. After all, Christina was HIV-positive. Instead I Holt International is dedicated to carrying out God’s plan for every child to have a permanent, loving family. found a girl on the cusp of adolescence who wore the unadorned, fresh beauty of In 1955 Harry and Bertha Holt responded to the conviction that youth. God had called them to help children left homeless by the Korean War. Though it took an act of the U.S. Congress, the Holts adopt- “So this is the face of AIDS,” I marveled. ed eight of those children. But they were moved by the desperate plight of other orphaned children in Korea and other countries In this issue of Holt International magazine, we feature a look at the range of as well, so they founded Holt International Children’s Services in order to unite homeless children with families who would love work Holt is doing around the world for children affected by HIV/AIDS. -

Bedtime) Story Ever Told

The Greatest (Bedtime) Story Ever Told By Brian T. Schultz The Greatest (Bedtime) Story Ever Told By Brian T. Schultz CAST of CHARACTERS (in order of appearance) Greta Jane Hank Esmerelda Katherine Jasmine Prunella Pocohontas Tortoise Megara Pirate Alice Evil Queen Sleeping Beauty 1st Little Pig Ariel ’Mother 2nd Little Pig Narco Handsome Prince Manic Driselda Smiley Papa Bear Fabio Goldilocks Crazy Old Dwarf Hare Drippy Fox Special Big Bad Wolf King Snow White Wicked Stepmother 3rd Little Pig Fairy Godmother Mama Bear Puss in Boots Jack Belle Cinderella Mulan Gingerbread Man Wendy Baby Bear TIME Now and Once Upon a Time PLACE Greta and ’bedroom The Forest The Castle The Bridge …and beyond “Greatest (Bedtime) Story Ever ”was originally produced by Aberdeen Community ’Young ’Theatre under the direction of Brian T. Schultz. It premiered on August 29, 2009 at the Capitol Theatre, Aberdeen, South Dakota. © 2009 Renaissance Artists Aberdeen, South Dakota, USA CAUTION: Professionals and amateurs are hereby warned that performance of this script (the "Play) is subject to payment of a royalty. It is fully protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America; all countries covered by the International Copyright Union (including the Dominion of Canada and the rest of the British Commonwealth); all countries covered by the Pan-American Copyright Convention, the Universal Copyright Convention and the Berne Convention; and of all countries with which the United States has reciprocal copyright relations. All rights, including without limitation professional/amateur stage rights, motion picture, recitation, lecturing, public reading, radio broadcasting, television, video or sound recording, all other forms of mechanical, electronic and digital reproduction, transmission and distribution, such as CD, DVD, Internet, private and file-sharing networks, information storage and retrieval systems, photocopying or any other form now known or yet to be invented and the rights of translation into foreign languages are strictly reserved. -

Discouraging Racial Preferences in Adoptions

Discouraging Racial Preferences in Adoptions Solangel Maldonado* More than 20,000 white Americans go abroad each year to adopt children from other countries, the majority of whom are not white. At the same time, there are more African American children available for adoption than there are African American families seeking to adopt them. While Americans claim there are few healthy infants available for adoption in the United States, hundreds of African American newborns each year are placed with white families in Canada and other countries. Tracing the history of transracial adoption in the United States, this Article argues that one reason why Americans go abroad to adopt is race. The racial hierarchy in the adoption market places white children at the top, African American children at the bottom, and children of other races in between, thereby rendering Asian or Latin American children more desirable to adoptive parents than African American children. Drawing on the rich literature on cognitive bias, this Article debunks the myths about domestic and international adoptions and shows that racial preferences, even if unconscious, play a role in many Americans’ decisions to adopt internationally. This Article proposes that the law discourage adoptions based on racial preferences by requiring that Americans seeking to adopt internationally, while there are available children in the United States who meet their non-race-based criteria, show non-race-based reasons for going abroad. * Associate Professor, Seton Hall University School of Law. J.D. 1996, Columbia Law School. I am grateful to Michelle Adams, Mark Alexander, Ruby Andrew, Carlos Bellido, Carl Coleman, Kevin Kelly, Jason Gardner, Timothy Glynn, Tristin Green, Rachel Godsil, Charlie Sullivan, the participants in the 12th International Society of Family Law Conference in Salt Lake City, the participants in the Second National POC in Washington, D.C., and the participants in the LatCrit X Conference in San Juan, Puerto Rico, for their helpful comments. -

It's Bedtime! Your Child’S Doctor

Resources OTHER RESOURCES It's Bedtime! Your child’s doctor. School Social Worker, counselor, psychologist or BOOKS FOR KIDS nurse. Tell Me Something Happy Before I Go to Counselors in the community. See both the yellow Sleep* by Debi Gliori and blue pages of the Lincoln Telephone book. Sea Otter Cove: A Relaxation Story by Lori Lite The Goodnight Caterpillar: A Children’s Relaxation Story by Lori Lite Be the Boss of Your Sleep by Timothy Culbert M.D. No Such Thing* by Jackie French Koller Sleep, Big Bear, Sleep* by Maureen Wright Dr. Seuss’s Sleep Book* by Dr. Seuss BOOKS FOR PARENTS Good Night, Sweet Dreams, I Love You by Patrick Friman Simplicity Parenting by Kim John Payne and Lisa Ross Solve your Child’s Sleep Problems* by Richard Ferber Healthy Sleep Habits, Happy Child* by Marc Weissbluth Starbright: Meditations for Children* by Maureen Garth The Sleep Lady’s Good Night, Sleep Tight: Gentle Proven Solutions to Help your Child Need help? Don’t know where to start? Bedtime. Sleep Well and Wake up Happy* by Kim West & Joanne Kenen Dial 2-1-1 or go to www.ne211.org. It's a word dreaded by many children. Inside are ideas to help bedtime be a pleasant time for families. Provided by LPS School Social Workers * Books available at Lincoln City Libraries BECAUSE FAMILIES MATTER Rev. 7/2015 routine to allow her time to finish what she is Share in your child’s bedtime routine. Your Bedtime doing. Sometimes setting a timer can be helpful. nurturing can help your child feel secure and be “Bedtime” is a word dreaded by many children. -

Why Fathers Matter to Their Children's Literacy

Why Fathers Matter to Their Children’s Literacy Christina Clark National Literacy Trust June 2009 Table of contents Introduction............................................................................................................... 3 Changing outlook on fatherhood ............................................................................. 3 Obstacles to family time.......................................................................................... 4 Father’s involvement in literacy............................................................................... 5 How are fathers involved with their children’s literacy activities? ...................... 7 Family life in Britain................................................................................................. 7 Father’s involvement in literacy............................................................................... 8 Defining literacy ...................................................................................................... 9 Mother vs. father involvement ............................................................................... 10 Involvement at different stages ............................................................................. 10 The benefits of father involvement ....................................................................... 11 The effects of father involvement on educational attainment and on literacy in particular ..............................................................................................................