Political Gerrymandering: Was Elbridge Gerry Right

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Shape of the Electoral College

No. 20-366 IN THE Supreme Court of the United States DONALD J. TRUMP, PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES, ET AL., Appellants, v. STATE OF NEW YORK, ET AL., Appellees. On Appeal From the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York BRIEF OF AMICUS CURIAE MICHAEL L. ROSIN IN SUPPORT OF APPELLEES PETER K. STRIS MICHAEL N. DONOFRIO Counsel of Record BRIDGET C. ASAY ELIZABETH R. BRANNEN STRIS & MAHER LLP 777 S. Figueroa St., Ste. 3850 Los Angeles, CA 90017 (213) 995-6800 [email protected] Counsel for Amicus Curiae TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS .................................................... i INTEREST OF AMICUS .................................................. 1 SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT .......................................... 2 ARGUMENT ....................................................................... 4 I. Congress Intended The Apportionment Basis To Include All Persons In Each State, Including Undocumented Persons. ..................... 4 A. The Historical Context: Congress Began to Grapple with Post-Abolition Apportionment. ............................................... 5 B. The Thirty-Ninth Congress Considered—And Rejected—Language That Would Have Limited The Basis of Apportionment To Voters or Citizens. ......... 9 1. Competing Approaches Emerged Early In The Thirty-Ninth Congress. .................................................. 9 2. The Joint Committee On Reconstruction Proposed A Penalty-Based Approach. ..................... 12 3. The House Approved The Joint Committee’s Penalty-Based -

Construction of the Massachusetts Constitution

Construction of the Massachusetts Constitution ROBERT J. TAYLOR J. HI s YEAR marks tbe 200tb anniversary of tbe Massacbu- setts Constitution, the oldest written organic law still in oper- ation anywhere in the world; and, despite its 113 amendments, its basic structure is largely intact. The constitution of the Commonwealth is, of course, more tban just long-lived. It in- fluenced the efforts at constitution-making of otber states, usu- ally on their second try, and it contributed to tbe shaping of tbe United States Constitution. Tbe Massachusetts experience was important in two major respects. It was decided tbat an organic law should have tbe approval of two-tbirds of tbe state's free male inbabitants twenty-one years old and older; and tbat it sbould be drafted by a convention specially called and chosen for tbat sole purpose. To use the words of a scholar as far back as 1914, Massachusetts gave us 'the fully developed convention.'^ Some of tbe provisions of the resulting constitu- tion were original, but tbe framers borrowed heavily as well. Altbough a number of historians have written at length about this constitution, notably Prof. Samuel Eliot Morison in sev- eral essays, none bas discussed its construction in detail.^ This paper in a slightly different form was read at the annual meeting of the American Antiquarian Society on October IS, 1980. ' Andrew C. McLaughlin, 'American History and American Democracy,' American Historical Review 20(January 1915):26*-65. 2 'The Struggle over the Adoption of the Constitution of Massachusetts, 1780," Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society 50 ( 1916-17 ) : 353-4 W; A History of the Constitution of Massachusetts (Boston, 1917); 'The Formation of the Massachusetts Constitution,' Massachusetts Law Quarterly 40(December 1955):1-17. -

John Adams, Political Moderation, and the 1820 Massachusetts Constitutional Convention: a Reappraisal.”

The Historical Journal of Massachusetts “John Adams, Political Moderation, and the 1820 Massachusetts Constitutional Convention: A Reappraisal.” Author: Arthur Scherr Source: Historical Journal of Massachusetts, Volume 46, No. 1, Winter 2018, pp. 114-159. Published by: Institute for Massachusetts Studies and Westfield State University You may use content in this archive for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the Historical Journal of Massachusetts regarding any further use of this work: [email protected] Funding for digitization of issues was provided through a generous grant from MassHumanities. Some digitized versions of the articles have been reformatted from their original, published appearance. When citing, please give the original print source (volume/number/date) but add "retrieved from HJM's online archive at http://www.westfield.ma.edu/historical-journal/. 114 Historical Journal of Massachusetts • Winter 2018 John Adams Portrait by Gilbert Stuart, c. 1815 115 John Adams, Political Moderation, and the 1820 Massachusetts Constitutional Convention: A Reappraisal ARTHUR SCHERR Editor's Introduction: The history of religious freedom in Massachusetts is long and contentious. In 1833, Massachusetts was the last state in the nation to “disestablish” taxation and state support for churches.1 What, if any, impact did John Adams have on this process of liberalization? What were Adams’ views on religious freedom and how did they change over time? In this intriguing article Dr. Arthur Scherr traces the evolution, or lack thereof, in Adams’ views on religious freedom from the writing of the original 1780 Massachusetts Constitution to its revision in 1820. He carefully examines contradictory primary and secondary sources and seeks to set the record straight, arguing that there are many unsupported myths and misconceptions about Adams’ role at the 1820 convention. -

The Federal Constitution and Massachusetts Ratification : A

, 11l""t,... \e ,--.· ', Ir \" ,:> � c.'�. ,., Go'.l[f"r•r•r-,,y 'i!i • h,. I. ,...,,"'P�r"'T'" ""J> \S'o ·� � C ..., ,' l v'I THE FEDERAL CONSTlTUTlON \\j\'\ .. '-1',. ANV /JASSACHUSETTS RATlFlCATlON \\r,-,\\5v -------------------------------------- . > .i . JUN 9 � 1988 V) \'\..J•, ''"'•• . ,-· �. J ,,.._..)i.�v\,\ ·::- (;J)''J -�·. '-,;I\ . � '" - V'-'� -- - V) A TEACHING KIT PREPAREV BY � -r THE COIJMOMVEALTH M,(SEUM ANV THE /JASSACHUSETTS ARCHIVES AT COLUM.BIA POINf ]') � ' I � Re6outee Matetial6 6ot Edueatot6 and {I · -f\ 066ieial& 6ot the Bieentennial 06 the v-1 U.S. Con&titution, with an empha6i& on Ma&&aehu&ett6 Rati6ieation, eontaining: -- *Ma66aehu6ett& Timeline *Atehival Voeument6 on Ma&&aehu&ett& Rati6ieation Convention 1. Govetnot Haneoek'6 Me&6age. �����4Y:t4���� 2. Genetal Coutt Re6olve& te C.U-- · .....1. *. Choo6ing Velegate& 6ot I\) Rati6ieation Convention. 0- 0) 3. Town6 &end Velegate Name&. 0) C 4. Li6t 06 Velegate& by County. CJ) 0 CJ> c.u-- l> S. Haneoek Eleeted Pte6ident. --..J s:: 6. Lettet 6tom Elbtidge Getty. � _:r 7. Chatge6 06 Velegate Btibety. --..J C/)::0 . ' & & • o- 8 Hane oe k Pt op o 6e d Amen dme nt CX) - -j � 9. Final Vote on Con&titution --- and Ptopo6ed Amenwnent6. Published by the --..J-=--- * *Clue6 to Loeal Hi&toty Officeof the Massachusetts Secretary of State *Teaehing Matetial6 Michaelj, Connolly, Secretary 9/17/87 < COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS !f1Rl!j OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY OF STATE CONSTITUTtON Michael J. Connolly, Secretary The Commonwealth Museum and the Massachusetts Columbia Point RATIFICATION OF THE U.S. CONSTITUTION MASSACHUSETTS TIME LINE 1778 Constitution establishing the "State of �assachusetts Bay" is overwhelmingly rejected by the voters, in part because it lacks a bill of rights. -

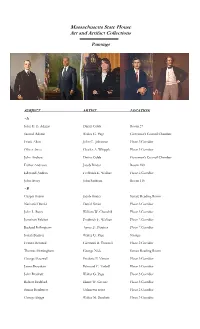

Open PDF File, 134.33 KB, for Paintings

Massachusetts State House Art and Artifact Collections Paintings SUBJECT ARTIST LOCATION ~A John G. B. Adams Darius Cobb Room 27 Samuel Adams Walter G. Page Governor’s Council Chamber Frank Allen John C. Johansen Floor 3 Corridor Oliver Ames Charles A. Whipple Floor 3 Corridor John Andrew Darius Cobb Governor’s Council Chamber Esther Andrews Jacob Binder Room 189 Edmund Andros Frederick E. Wallace Floor 2 Corridor John Avery John Sanborn Room 116 ~B Gaspar Bacon Jacob Binder Senate Reading Room Nathaniel Banks Daniel Strain Floor 3 Corridor John L. Bates William W. Churchill Floor 3 Corridor Jonathan Belcher Frederick E. Wallace Floor 2 Corridor Richard Bellingham Agnes E. Fletcher Floor 2 Corridor Josiah Benton Walter G. Page Storage Francis Bernard Giovanni B. Troccoli Floor 2 Corridor Thomas Birmingham George Nick Senate Reading Room George Boutwell Frederic P. Vinton Floor 3 Corridor James Bowdoin Edmund C. Tarbell Floor 3 Corridor John Brackett Walter G. Page Floor 3 Corridor Robert Bradford Elmer W. Greene Floor 3 Corridor Simon Bradstreet Unknown artist Floor 2 Corridor George Briggs Walter M. Brackett Floor 3 Corridor Massachusetts State House Art Collection: Inventory of Paintings by Subject John Brooks Jacob Wagner Floor 3 Corridor William M. Bulger Warren and Lucia Prosperi Senate Reading Room Alexander Bullock Horace R. Burdick Floor 3 Corridor Anson Burlingame Unknown artist Room 272 William Burnet John Watson Floor 2 Corridor Benjamin F. Butler Walter Gilman Page Floor 3 Corridor ~C Argeo Paul Cellucci Ronald Sherr Lt. Governor’s Office Henry Childs Moses Wight Room 373 William Claflin James Harvey Young Floor 3 Corridor John Clifford Benoni Irwin Floor 3 Corridor David Cobb Edgar Parker Room 222 Charles C. -

Accounts Committee, 70. 186 Adams. Abigail, 56 Adams, Frank, 196

Index Accounts Committee, 70. 186 Appropriations. Committee on (House) Adams. Abigail, 56 appointment to the, 321 Adams, Frank, 196 chairman also on Rules, 2 I I,2 13 Adams, Henry, 4 I, 174 chairman on Democratic steering Adams, John, 41,47, 248 committee, 277, 359 Chairmen Stevens, Garfield, and Adams, John Quincy, 90, 95, 106, 110- Randall, 170, 185, 190, 210 111 created, 144, 167. 168, 169, 172. 177, Advertisements, fS3, I95 184, 220 Agriculture. See also Sugar. duties on estimates government expenditures, 170 Jeffersonians identified with, 3 1, 86 exclusive assignment to the, 2 16, 32 1 prices, 229. 232, 261, 266, 303 importance of the, 358 tariffs favoring, 232, 261 within the Joint Budget Committee, 274 Agriculture Department, 303 loses some jurisdiction, 2 10 Aid to Families with Dependent Children members on Budget, 353 (AFDC). 344-345 members on Joint Study Committee on Aldrich, Nelson W., 228, 232. 241, 245, Budget Control, 352 247 privileged in reporting bills, 185 Allen, Leo. 3 I3 staff of the. 322-323 Allison, William B., 24 I Appropriations, Committee on (Senate), 274, 352 Altmeyer, Arthur J., 291-292 American Medical Association (AMA), Archer, William, 378, 381 Army, Ci.S. Spe also War Department 310, 343, 345 appropriation bills amended, 136-137, American Newspaper Publishers 137, 139-140 Association, 256 appropriation increases, 127, 253 American Party, 134 Civil War appropriations, 160, 167 American Political Science Association, Continental Army supplies, I7 273 individual appropriation bills for the. American System, 108 102 Ames, Fisher, 35. 45 mobilization of the Union Army, 174 Anderson, H. W., 303 Arthur, Chester A,, 175, 206, 208 Assay omces, 105, 166 Andrew, John, 235 Astor, John Jacob, 120 Andrews, Mary. -

TO SIGN OR NOT to SIGN Lesson Plan to SIGN OR NOT to SIGN

TO SIGN OR NOT TO SIGN Lesson Plan TO SIGN OR NOT TO SIGN ABOUT THIS LESSON AUTHOR On Constitution Day, students will examine the role of the people in shaping the United States Constitution. First, students National Constitution Center will respond to a provocative statement posted in the room. They will then watch a video that gives a brief explanation of the Constitutional Convention of 1787, or listen as the video transcript is read aloud. A Constitution poster is provided so students can examine Article VII and discuss it as a class. The elementary and middle school educator will then guide students through a read-aloud play depicting two Constitutional Convention delegates who disagreed about ratifying the Constitution. High school students will review support materials and have a class debate about why delegates should or should not have signed the Constitution in 1787. The class will then discuss the ratification process. The lesson closes with an opportunity for students to sign the Constitution, if they choose, and to discuss what it means to sign or not sign. TO SIGN OR NOT TO SIGN 2 BaCKGROUND GRADE LEVEL(S) September 17, 1787 was the final day of the Constitutional Convention, when 39 of the men present in Philadelphia Elementary, Middle, High School chose to sign the document. Signing put their reputations on the line. Their signatures gave weight to the document, ClaSSROOM TIME but it was the subsequent ratification contest that really 45 minutes mattered. Ratification embodied the powerful idea of popular sovereignty—government by the people—that has been at the heart of the Constitution from its inception until today. -

John-Adams-3-Contents.Pdf

Contents TREATY COMMISSIONER AND MINISTER TO THE NETHERLANDS AND TO GREAT BRITAIN, 1784–1788 To Joseph Reed, February 11, 1784 Washington’s Character ....................... 3 To Charles Spener, March 24, 1784 “Three grand Objects” ........................ 4 To the Marquis de Lafayette, March 28, 1784 Chivalric Orders ............................ 5 To Samuel Adams, May 4, 1784 “Justice may not be done me” ................... 6 To John Quincy Adams, June 1784 “The Art of writing Letters”................... 8 From the Diary: June 22–July 10, 1784 ............. 9 To Abigail Adams, July 26, 1784 “The happiest Man upon Earth”................ 10 To Abigail Adams 2nd, July 27, 1784 Keeping a Journal .......................... 12 To James Warren, August 27, 1784 Diplomatic Salaries ......................... 13 To Benjamin Waterhouse, April 23, 1785 John Quincy’s Education ..................... 15 To Elbridge Gerry, May 2, 1785 “Kinds of Vanity” .......................... 16 From the Diary: May 3, 1785 ..................... 23 To John Jay, June 2, 1785 Meeting George III ......................... 24 To Samuel Adams, August 15, 1785 “The contagion of luxury” .................... 28 xi 9781598534665_Adams_Writings_791165.indb 11 12/10/15 8:38 AM xii CONteNtS To John Jebb, August 21, 1785 Salaries for Public Officers .................... 29 To John Jebb, September 10, 1785 “The first Step of Corruption”.................. 33 To Thomas Jefferson, February 17, 1786 The Ambassador from Tripoli .................. 38 To William White, February 28, 1786 Religious Liberty ........................... 41 To Matthew Robinson-Morris, March 4–20, 1786 Liberty and Commerce....................... 42 To Granville Sharp, March 8, 1786 The Slave Trade............................ 45 To Matthew Robinson-Morris, March 23, 1786 American Debt ............................ 46 From the Diary: March 30, 1786 .................. 49 Notes on a Tour of England with Thomas Jefferson, April 1786 ............................... -

Massachusetts Art Commission

Massachusetts State House Art Collection Index of Artists, Foundries, and Carvers ARTIST TITLE OBJECT ~A ADAMS, Herbert Charles Bulfinch plaque – bronze, 1898 State House Preservation plaque – bronze, 1898 AMES, Sarah Fisher Clampitt Abraham Lincoln bust – marble, 1867 ANDERSON, Robert A. Edward King painting, 1990 William F. Weld painting, 2002 ANDREW, Richard Veterans of the Sixth Regiment Memorial mural series, 1932 Decoration of the Colors of the 104th Infantry mural, 1927 ANNIGONI, Pietro John A. Volpe painting, 1963 AUGUSTA, George Francis Sargent painting, 1975 ~B BACON, Henry William F. Bartlett statue base, 1905 Joseph Hooker statue base, 1903 Roger Wolcott/Spanish War Memorial statue base, 1906 BAKER, Samuel Burtis Curtis Guild, Jr. painting, c. 1919 BALL, Thomas John A. Andrew statue – marble, 1872 BARTLETT, George H. Arthur B. Fuller bust –plaster, c. 1863 BELCHETZ-Swenson, Sarah Jane M. Swift painting, 2005 BENSON, John John F. Kennedy plaque – slate, 1972 BENSON, Frank W. Levi Lincoln, Jr. painting, 1900 William B. Washburn painting, 1900 BERGMANN, Meredith Edward Cohen/Massachusetts Labor History plaque – bronze, 2009 BICKNELL, Albion H. Abraham Lincoln painting, 1905 BINDER, Jacob Esther Andrews painting, 1931 Gaspar Bacon painting, 1939 Charles F. Hurley painting, 1940 BLAKE, William S. Hancock House plaque – bronze, l. 19th c. BORGLUM, Gutzon Theodore Roosevelt bust - bronze, 1919 BRACKETT, Walter M. George N. Briggs painting, 1849 BRODNEY, Edward Columbia Knighting her War Disabled mural, 1936 The War Mothers mural, 1938 BROOKS, Richard E. William E. Russell bust – bronze, 1893 Gardiner Tufts bust – marble, 1892 Massachusetts State House Art Collection: Index of Artists, Foundries, and Carvers BRYANT, Wallace Rev. -

Or Attaining Other Committee Members Serving in Higher Offices Accomplishments

Committee Members Serving in Higher Offices or Attaining Other Accomplishments MEMBERS OF CONTINENTAL John W. Jones John Sherman CONGRESS Michael C. Kerr Abraham Baldwin Nicholas Longworth SECRETARIES OF THE TREASURY Elias Boudinot John W. McCormack George W. Campbell Lambert Cadwalader James K. Polk John G. Carlisle Thomas Fitzsimons Henry T. Rainey Howell Cobb Abiel Foster Samuel J. Randall Thomas Corwin Elbridge Gerry Thomas B. Reed Charles Foster Nicholas Gilman Theodore Sedgwick Albert Gallatin William Hindman Andrew Stevenson Samuel D. Ingham John Laurance John W. Taylor Louis McLane Samuel Livermore Robert C. Winthrop Ogden L. Mills James Madison John Sherman John Patten SUPREME COURT JUSTICES Phillip F. Thomas Theodore Sedgwick Philip P. Barboar Fred M. Vinson William Smith Joseph McKenna John Vining John McKinley ATTORNEYS GENERAL Jeremiah Wadsworth Fred M. Vinson, ChiefJustice James P. McGranery Joseph McKenna SIGNER OF THE DECLARATION OF PRESIDENTS A. Mitchell Palmer INDEPENDENCE George H.W. Bush Caesar A. Rodney Elbridge Gerry Millard Fillmore James A. Garfield POSTMASTERS GENERAL DELEGATES TO Andrew Jackson CONSTITUTIONAL CONVENTION Samuel D. Hubbard James Madison Cave Johnson Abraham Baldwin William McKinley Thomas Fitzsimons James K. Polk Horace Maynard William L. Wilson Elbridge Gerry John Tyler Nicholas Gilman SECRETARIES OF THE NAVY James Madison VICE PRESIDENTS Thomas W. Gilmer John C. Breckinridge SIGNERS OF THE CONSTITUTION Hilary A. Herbert George H.W. Bush OF THE UNITED STATES Victor H. Metcalf Charles Curtis Abraham Baldwin Claude A. Swanson Millard Fillmore Thomas Fitzsimons John Nance Garner Nicholas Gilman SECRETARIES OF THE INTERIOR Elbridge Gerry James Madison Richard M. Johnson Rogers C.B. Morton John Tyler Jacob Thompson SPEAKERS OF THE HOUSE Nathaniel P. -

College of the Holy Cross Archives and Special Collections P.O

College of the Holy Cross Archives and Special Collections P.O. Box 3A, Worcester, MA 01610-2395 College of the Holy Cross Archives and Special Collections Collection Inventory Accession Number: SC2000-75 Collection Name (Title): O’Connor, Patrick Collection Dates of Material: 1578- 20th Century Size of Collection: 1 Box, 39 Folders Arrangement: Restrictions: Related Material: Preferred Citation: Processed on: March 18, 2008 Biography/History: Patrick F. O’Connor was born in Cahirciveen, Ireland in 1909. He attended Boston College High School, and graduated from Holy Cross in 1932. He also attended University of Cambridge in Oxford, England. He was a veteran of World War II. O’Connor was the head of the English Department at Boston Technical High. He died November 5, 2001. Scope and Content Note: This collection was assembled by Patrick O’Connor. It consists of assorted documents, each with an autograph of a governor of Massachusetts. There are 36 governors autographs arranged chronologically with each autograph in its own folder. The collection begins with John Hancock who served from 1780-85 and ends with Ebenezer Draper who served, 1901-1911. There are two folders in the collection that contain miscellaneous paper and vellum documents that date to 1578 that were also collected by O’Connor. The final folder has information on the collection itself. http://holycross.edu/archives-and-special-collections 1 College of the Holy Cross Archives and Special Collections P.O. Box 3A, Worcester, MA 01610-2395 Box and Folder List: Box 1: Folder 1: Hancock, John, 1780-1785 Folder 2: Bowdoin, James – 1785-1787 Folder 3: Samuel Adams –1793 - 1797 Folder 4: Increase Sumner –1797 -1799 Folder 5: Moses Gill –1794-1799, 1799-1800 Folder 6: Caleb Strong –1800 -1807 Folder 7: James A. -

St. S House, Boston

«lIly.e OI.ommonfu.ea:Jtly of ~55UlyuUtt5 Massachusetts Art Commission State House Room 10 Boston, MA 02133 tel. (617) 727-2607, ext. 517 fax (617) 727-5400 Peter L Walsh ANNUAL REPORT Chairman Bonita A. Rood YEAR ENDING JUNE 30, 1996 Arlene E. Friedberg Paula M. Kozol Katherine B. Winter The Massachusetts Art Commission respectfully submits the Annual Report for the year ending June 30, 1996. The Art Commission is charged under General Laws chapter 6, sections 19 and 20 with "the care and custody oj all historical relics in the State House, and oj all works oj art." As the appointed curators, it is the responsibility of the Art Commission to insure that this growing museum quality collection is professionally handled, properly maintained and appropriately displayed. The Commission receives annual legislative appropriations for its programs, distributed through the Bureau of State Office Buildings. We are pleased to report on another busy and successful year of activities. ART CONSERVATION PROGRAMS I. Paintings and frames, August-December 1995. The Art Commission continued its program of conservation and preservation of the State House art collection with the cleaning and professional treatment of several portraits and their frames. Contracts were issued in August to Carmichael Conservation, Methuen, and Gianfranco Pocobene, Malden, for treatment of eleven easel paintings which exhibited a variety of conservation conditions including discolored varnish, grime, stains, and abrasion. Contracts were also awarded to Susan Jackson, Harvard, and Trefler & Sons, Needham, to address ten frames which had experienced chipping and other damage to plaster and gesso decoration, abrasion, loss of gold leaf, and discolored over-painting.