Refinement and Architecture in Early Ypsilanti Lynda Mccarron

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE GILDED GARDEN Historic Ornament in the Landscape at Montgomery Place

DED GA GIL RD E E H N T Historic Ornament in the Landscape at Montgomery Place May 25 – October 31, 2019 1 THE GILDED GARDEN Historic Ornament in the Landscape at Montgomery Place In 1841, the renowned American architect Alexander Jackson Davis (1803–92) was hired to redesign the Mansion House at Montgomery Place, as well as consult on the surrounding grounds. Between 1841 and 1844, Davis introduced the property owners Louise Livingston, her daughter Cora, and son-in-law Thomas Barton to Exhibition produced in partnership with and curated by landscape designer, editor, and writer Andrew Jackson Downing (1815–52), the Barbara Israel and her staff from Barbara Israel Garden Antiques seminal figure now regarded by historians as the father of American landscape architecture. Downing had learned practical planting know-how at his family’s nursery, but he was more than an expert on botanical species. He was also a Funding provided by the A. C. Israel Foundation and tastemaker of the highest order who did more to influence the way Americans Plymouth Hill Foundation designed their properties than anyone else before or since. Raised in Newburgh, Downing was intensely devoted to the Hudson Valley region and was dedicated to his family’s nursery business there. In the 1830s, Downing began to make a name for himself as a writer, and contributed multiple articles on horticulture to various periodicals. Downing’s enormously influential work,A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, Adapted to North America was published in 1841. It contained descriptions of the proper use of ornament, the importance of coherent design, use of native trees and plants, and his most important principle—that, when it came to designing a landscape, nature should be elevated and interpreted, not slavishly copied. -

Of Irvington, New York, 1849,1860 by Rohit T

The Hudson River Railroad and the Development of Irvington, New York, 1849,1860 By Rohit T. Aggarwala Introduction Close by Sunnyside is one of those marvelous villages with which America abounds: it has sprung up like a mushroom, and bears the name Irvington, in compliment to the late master of Sunnyside. A dozen years ago, not a solitary house was there .... Piermont, directly oppos ite, was then the sole terminus of the great New York and Erie Railway, and here seemed to be an eligible place for a village, as the Hudson River Railway was then almost completed. Mr. Dearman had one surveyed upon his lands; streets were marked out, village lots were measured and defined; sales at enormous prices, which enriched the owner, were made, and now upon that farm, in pleas ant cottages, surrounded by neat gard ens, several hundred inhabi tants are dwelling .... Morning and evening, when the trains depart for and arrive from New York, many handsome vehicles can be seen there. This all seems like the work of magic. O ver this beautiful slope, where so few years ago the voyager upon the Hudson saw only woodlands and cultivated fields, is now a populous town. The own ers are chiefl y business in [sic] of N ew York, whose counting rooms and parlours are within less than an hour of each other. - Benson J. Lossing, The Hudson, 18661 Tht Hudson River Rail road and the Development of Irvington, New York, 1849- 1860 51 Irvington, New York, was created by the coming of the Hudson River Railroad. -

Andrew Jackson Downing, 1815–1852

The AAG Review OF BOOKS Apostle of Taste: Andrew Jackson Downing, 1815–1852 David Schuyler. Amherst, MA: socializing benefit that shaped U.S. University of Massachusetts landscape taste in ways we still value. Press, 2015. xxii and 290 pp., illustrations, appendices, notes, Downing wanted to influence a demo- bibliography, index. $24.95 paper cratic civil society through an intel- (ISBN 978-1-62534-168-6). lectual and moral middle-class aes- thetic, and design a landscape that Reviewed by Joseph S. Wood, would bring antebellum Americans Departments of History and across social classes together. Still to- Public Affairs, University of day, U.S. small towns and villages, and even an occasional farmscape, exhibit Baltimore, Baltimore, MD. nineteenth-century Downing-inspired English or Italianate-styled houses, and sometimes a classical vernacular Why would geographers wish to read form festooned with a gothic gable or an assessment of the work of ante- board-and-batten siding and brack- bellum U.S. landscape gardener and eted overhangs. Early elite watering architect Andrew Jackson Downing? holes, such as Newport, Rhode Island, Today we take “landscaping” for exhibit relict mansions and gardens, granted, and in much of the United likewise inspired by Downing’s vision States we hire “landscapers,” often immigrants and day of taste and refinement, albeit in his simplified, Ameri- laborers, to maintain for us what in the 1840s was a can adaptation. So, too, do urban parks and suburbs that new and exciting vision. That vision has led to a wide- eschew the grid. Quite simply, if one wishes to read and spread vernacular form of lawns and gardens, albeit make sense of today’s U.S. -

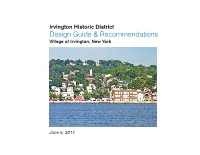

Design Guide & Recommendations

Irvington Historic District Design Guide & Recommendations Village of Irvington, New York June 5, 2017 INTENDED USE OF THE IRVINGTON HISTORIC DISTRICT DESIGN GUIDE AND RECOMMENDATIONS VILLAGE OF IRVINGTON, NY On June 19, 2017, the Board of Trustees of the Village of Irvington adopted the Historic District Design Guide and Recommendations. In doing so, the Board of Trustees passed a Resolution 2017-094 memorializing its intent on how the guide should be applied. Below is a copy of that resolution. RESOLUTION 2017-094 ADOPTION OF HISTORIC DISTRICT DESIGN GUIDE AND RECOMMENDATIONS WHEREAS, the 2003 Comprehensive Plan recommended WHEREAS, in January 2014, the Irvington Historic the designation of the Main Street area as a historic district and the District was officially listed on the National Register of Historic adoption of a historic district ordinance; and Places; and WHEREAS, in February 2010, the Board of Trustees, in WHEREAS, the designation on the National Register recognition of the distinctive and important historical and applies to the Main Street area as a whole, rather than to any architectural identity of the Main Street Area, amended the Board individual house in the Irvington Historic District; and of Architectural Review chapter of the Village Code to list as one of its purposes, “Protect the historic character of the Village, WHEREAS, the Historic District Committee, in including, in particular, the Main Street Historic Area,” but did not consultation with Stephen Tilley Associates, developed the provide specific guidance -

View / Download

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 (Oct. 1990) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations of eligibility for individual properties or districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories listed in the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property historic name Anderson Park other names/site number Montclair Park 2. Location street & number SE corner of Bellevue and North Mountain Avenues not for publication city or town Montclair Township vicinity state New Jersey code NJ county Essex code 013 zip code 07043 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I certify that this nomination request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property meets does not meet the National Register criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant nationally statewide locally. -

Commemorative Works Catalog

DRAFT Commemorative Works by Proposed Theme for Public Comment February 18, 2010 Note: This database is part of a joint study, Washington as Commemoration, by the National Capital Planning Commission and the National Park Service. Contact Lucy Kempf (NCPC) for more information: 202-482-7257 or [email protected]. CURRENT DATABASE This DRAFT working database includes major and many minor statues, monuments, memorials, plaques, landscapes, and gardens located on federal land in Washington, DC. Most are located on National Park Service lands and were established by separate acts of Congress. The authorization law is available upon request. The database can be mapped in GIS for spatial analysis. Many other works contribute to the capital's commemorative landscape. A Supplementary Database, found at the end of this list, includes selected works: -- Within interior courtyards of federal buildings; -- On federal land in the National Capital Region; -- Within cemeteries; -- On District of Columbia lands, private land, and land outside of embassies; -- On land belonging to universities and religious institutions -- That were authorized but never built Explanation of Database Fields: A. Lists the subject of commemoration (person, event, group, concept, etc.) and the title of the work. Alphabetized by Major Themes ("Achievement…", "America…," etc.). B. Provides address or other location information, such as building or park name. C. Descriptions of subject may include details surrounding the commemorated event or the contributions of the group or individual being commemorated. The purpose may include information about why the commemoration was established, such as a symbolic gesture or event. D. Identifies the type of land where the commemoration is located such as public, private, religious, academic; federal/local; and management agency. -

Alexander Jackson Downing Years: October 31, 1815

Elijah Bender Hudson River Valley Institute Name: Alexander Jackson Downing Years: October 31, 1815 – July 28, 1852 Residence: Newburgh, NY Biography: Andrew Jackson Downing was born in Newburgh in 1815 and is regarded as one of the pioneers in American landscape architecture and design. An avid horticulturist, Downing’s father was an expert nurseryman and this propelled Image via Montgomery Place http://american- Downing toward the study of botany. arcadia.hudsonvalley.org/content/friend-muse1 Downing is credited for his designing and landscaping of the White House, United States Capitol, and the Smithsonian Institute. Downing was a staunch advocate of public parks and for an appreciation of the natural environment in a period of rapid, industrialized change. Downing was also greatly influenced by English horticulturalist and author, J.C. Loudon. Downing would go on to write A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, Adapted to North America, his first book, written in 1841. Downing would later meet the young student, Calvert Vaux, subsequently partnering and designing landscapes for estates in the Hudson River Valley and environs. Later, Downing, Vaux, and Frederick Law Olmstead would begin discussions on a design for Central Park in Manhattan to feature a zoo, gardens, art galleries, science museum, and other features. Downing died in 1852 as a result of a paddle boat accident en route to Newburgh with his family. Olmstead and Vaux would continue designs for Central Park which came to fruition in 1857. Accomplishments: Downing is well regarded as a pioneer in American landscape architecture and for his advocacy of large urban parks, laying the groundwork for plans for Central Park in New York with the aid of Calvert Vaux and Frederick Law Olmstead. -

Waterfronts for Work and Play: Mythscapes of Heritage and Identity in Contemporary Rhode Island

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: WATERFRONTS FOR WORK AND PLAY: MYTHSCAPES OF HERITAGE AND IDENTITY IN CONTEMPORARY RHODE ISLAND Kristen A. Williams, Doctor of Philosophy, 2010 Dissertation directed by: Dr. Nancy L. Struna Department of American Studies My dissertation examines the relationship between heritage sites, urban culture, and civic life in present-day Rhode Island, evaluating how residents‟ identities and patterns of civic engagement are informed by site-specific tourist narratives of eighteenth, nineteenth and early twentieth-century labor histories. Considering the adaptive reuse of former places of maritime trade and industry as contemporary sites of leisure, I analyze the role that historic tourism plays in local and regional economic urban redevelopment. I argue that the mythscapes of exceptionalism mobilized at Rhode Island‟s heritage sites create usable pasts in the present for current residents and visitors alike, alternatively foregrounding and obscuring intersectional categories of difference according to contemporaneous political climates at the local, national and transnational levels. This study is divided into two parts, organized chronologically and geographically. While Part I examines the dominant tourist narratives associated with Newport County, located in the southeast of the state and including Aquidneck Island (also known as Rhode Island), Part II takes the historic tourism associated with mainland Providence Plantations as its case study and focuses exclusively on Providence County, covering the middle -

Viewed Within the Context of the Development of the Romantic

The Hoyt House (The Point) – Historic Background Summary by William Krattinger (Historic Preservation Specialist, New York State Historic Preservation Office) Viewed within the context of the development of the Romantic-inspired villa in American domestic architecture, a period roughly initiated by Town & Davis's design for Glen Ellen, Baltimore, 1833, and culminating in the completion of Olana in 1872, the Hoyt House retains a significant position. The body of work that Vaux contributed to this evolution is considerable. As a protégé of Andrew Jackson Downing, the young Vaux and his fellow Englishman F.C. Withers were charged with carrying on their mentor's work following his untimely death in 1852. During the 1850s, Vaux produced some of the more noteworthy domestic compositions in the Picturesque vein in the United States, among them the Warren and Hoyt houses, and in so doing successfully continued Downing's legacy while evolving his own personal interpretation of Romantic architectural design. This is in addition to the significant work Vaux performed in collaboration with Frederick Law Olmsted in designing Manhattan’s Central Park and Brooklyn’s Prospect Park, among others. Vaux, along with Jacob Wrey Mouls, also designed the original Museum of Natural History and Metropolitan Museum of Art structures, among his other creations located throughout New York State. Although currently suffering from long deferred maintenance and vandalism, the Hoyt House maintains a considerable presence and many of the salient characteristics that mark it as the work of Calvert Vaux. Its handsomely tooled bluestone walls, having now acquired the luminous but mellow tint and varied texture Vaux desired, remain an impressive monument to the men who dressed and laid them up, and a testament to Vaux's thoughtful planning and considerable comprehension of site specificity. -

C.Arden (Bookseller) – Website Our Website Is Now 2 Years Old and Regularly Updated with New Stock

C. Arden, Bookseller ‘Radnor House’, Church Street, Hay-on-Wye, (via) Hereford, HR3 5DQ, U.K. Tel: +44 (0) 1497-820471 Fax: +44 (0) 1497-820498 Email: [email protected] Web: www.ardenbooks.co.uk Catalogue No.90 Botany 1 – 162 Darwin 163 - 188 Entomology 189 – 221 Fine, Illustrated & Antiquarian 222 – 236 Gardening 237 – 364 Natural History 365 – 460 New Naturalists – Main series 461 – 572 New Naturalists – Monographs 573 – 593 Ornithology 594 – 908 Zoology 909 – 983 New Naturalists The most recent title No.115 ‘Climate and Weather’ was published at the end of August and has been a popular title. We have several copies left (see item 572 in this catalogue). We expect to take delivery of NN.116 ‘Plant Pests’ by David Alford in early January 2011. We will charge catalogue customers £45.00 plus post (RRP £50.00) and if you would like a copy, do let us know. There are a number of special offers in our listing of New Naturalists. Ornithology We have listed a very large number of titles in our ornithology section. This comprises a recently purchased ornithological collection which includes quite a number of specialist titles on Hummingbirds. C.Arden (bookseller) – website Our website is now 2 years old and regularly updated with new stock. We have also added several thousand book images which we hope makes purchasing easier. Bee & Bee-keeping book catalogue Our stock of new, second-hand and antiquarian bee & bee-keeping books continues to grow. We now have around 300 titles. We now publish dedicated bee & beekeeping book catalogues and list stock on our website. -

WIS LJ 341 01 Makker.Indd

Mary G. Hopkins and the Origins of Village Improvement in Antebellum Stockbridge, Massachusetts Kirin J. Makker ABSTRACT The Laurel Hill Association of Stockbridge, INTRODUCTION Massachusetts, generally considered the first village The Laurel Hill Association of Stockbridge, Massa- improvement society in the country, was founded in chusetts, generally considered the fi rst village improve- 1853 at the urging of a local citizen and native of the town, ment society in America, was founded by a group of Mary G. Hopkins. This paper examines the discussions local citizens on August 26, 1853 (Figure 1). The fi rst among members of her generation and class that set the two years of the Association’s work were remarkably stage for Hopkins’ promotional campaign and, eventu- successful. In mid- May, 1854, the Executive Commit- ally, the wide acceptance of her ideas as village improve- tee discussed the “merits of hedges and particularly ment spread through New England and then across the concerning the pretentions of Norway spruce” as the United States. Specifically, this study delves into a his- best way to handle the boundary of a town cemetery tory of social activism, moral reform, and theories about under improvement. In discussing the options, the taste occurring in Stockbridge, the Berkshires, and New group considered the recently published 1853 collection England between 1800–1853. Life histories of several of Andrew Jackson Downing’s Rural Essays, perhaps members of Hopkins’ family, friends, and associates brought to the meeting by Mary Hopkins. The Execu- are described, helping to shape a picture of the values, tive Committee minutes note, “Mr. -

Villas on the Hudson: an Architectural and Biographical Examination

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research Lehman College 1993 Villas on the Hudson: An Architectural and Biographical Examination Janet Butler Munch Lehman College, CUNY How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/le_pubs/229 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] AM E RICAN P U BLISHER S ' CIR CU LAR ======~~~~~====~==== nono L 1860. IN PRESS BY BOSTON TRADE SALE WI LL Cmnl[XCC WEDNESDAY MORNING, D. APPLETON &: COMPANY, ACGCST 1, 1800. r. I' r U l ~. m . W rn A T ,' .. n.ead k Co. ~:~ r-);. 'r ~':7:·: . ~~ ro ~ :~~,L ~~ ~ ~' ~" '\· ~ I . , •. \\" •• & (' 0 C ~ I 5 "" " 0. D.," rr "- Co. TI:I,.N "'1.I.,lr .. lr~ J,. I," \\' ,,~ ~ J ... "., ~L u""~, .... ":0. Coillo. '" IIr o: ~", 1,IIII ·, oI. II L•. ,r . TnE EBOXY IDO L. A :NOl' ti, wriUen by .. Lady of Sew r esiDed. C I• • k. -, "011". ~ Ior n •• d '" ""0 (; 1\ 1 ' ''I 'r ~1I C~ • • lr. :! ,' , . , f lO 4: <.: " II "" .. 1I "r 1:1' " 4: ~ 1 '''U '' '' O '''''C J H l ' l'i" h,oll oi Co LIFE OF 'IHLLI.U! T. PORTER, Ili te EJ itor of .. POtl er', Spirit of the ,., W OuJ" 11 1• .,, 10 . "1 ,\.1 .... Ap Jll r ~ . , .. .. ('D. J\ ~ "' . u. 4: Ti... eo . ~ J C.. G oI. l'. Mr , n . m. or II I' .. ,~, ,, n .. lI.alb" • •• J uhn t::Kch rJ' lry ( bll,i ...