An Optimist's View of Dark Matter and How to Find It By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Adrien Christian René THOB

THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN THE MORPHOLOGY AND KINEMATICS OF GALAXIES AND ITS DEPENDENCE ON DARK MATTER HALO STRUCTURE IN SIMULATED GALAXIES Adrien Christian René THOB A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Liverpool John Moores University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. 26 April 2019 To my grand-parents, René Roumeaux, Christian Thob, Yvette Roumeaux (née Bajaud) and Anne-Marie Thob (née Léglise). ii Abstract Galaxies are among nature’s most majestic and diverse structures. They can play host to as few as several thousands of stars, or as many as hundreds of billions. They exhibit a broad range of shapes, sizes, colours, and they can inhabit vastly differing cosmic environments. The physics of galaxy formation is highly non-linear and in- volves a variety of physical mechanisms, precluding the development of entirely an- alytic descriptions, thus requiring that theoretical ideas concerning the origin of this diversity are tested via the confrontation of numerical models (or “simulations”) with observational measurements. The EAGLE project (which stands for Evolution and Assembly of GaLaxies and their Environments) is a state-of-the-art suite of such cos- mological hydrodynamical simulations of the Universe. EAGLE is unique in that the ill-understood efficiencies of feedback mechanisms implemented in the model were calibrated to ensure that the observed stellar masses and sizes of present-day galaxies were reproduced. We investigate the connection between the morphology and internal 9:5 kinematics of the stellar component of central galaxies with mass M? > 10 M in the EAGLE simulations. We compare several kinematic diagnostics commonly used to describe simulated galaxies, and find good consistency between them. -

Current Perspectives on Dark Matter

Cosmological Signatures of a Mirror Twin Higgs Zackaria Chacko University of Maryland, College Park Curtin, Geller & Tsai Introduction The Twin Higgs framework is a promising approach to the naturalness problem of the Standard Model (SM). In Mirror Twin Higgs models, the SM is extended to include a complete mirror (“twin”) copy of the SM, with its own particle content and gauge groups. The SM and its twin counterpart are related by a discrete Z2 “twin” symmetry. Z2 SMA SMB The mirror particles are completely neutral under the SM strong, weak and electromagnetic forces. Only feel gravity. In Mirror Twin Higgs models, the one loop quadratic divergences that contribute to the Higgs mass are cancelled by twin sector states that carry no charge under the SM gauge groups. Discovery of these states at LHC is therefore difficult. May explain null results. The SM and twin SM primarily interact through the Higgs portal. This interaction is needed for cancellation of quadratic divergences. After electroweak symmetry breaking, SM Higgs and twin Higgs mix. • Higgs couplings to SM states are suppressed by the mixing. • Higgs now has (mixing suppressed) couplings to twin states. A soft breaking of the Z2 symmetry ensures that 퐯B, the VEV of the twin Higgs, is greater than 퐯A, the VEV of the SM Higgs. The mixing angle ~ 퐯A/퐯B. Higgs measurements constrain 퐯A/퐯B ≤ ퟏ/ퟑ. Twin fermions are heavier than SM fermions by a factor of 퐯B/퐯A . Naturalness requires 퐯A/퐯B ≥ ퟏ/ퟓ. (Twin top should not be too heavy.) The Higgs portal interaction has implications for cosmology. -

Particle Dark Matter an Introduction Into Evidence, Models, and Direct Searches

Particle Dark Matter An Introduction into Evidence, Models, and Direct Searches Lecture for ESIPAP 2016 European School of Instrumentation in Particle & Astroparticle Physics Archamps Technopole XENON1T January 25th, 2016 Uwe Oberlack Institute of Physics & PRISMA Cluster of Excellence Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz http://xenon.physik.uni-mainz.de Outline ● Evidence for Dark Matter: ▸ The Problem of Missing Mass ▸ In galaxies ▸ In galaxy clusters ▸ In the universe as a whole ● DM Candidates: ▸ The DM particle zoo ▸ WIMPs ● DM Direct Searches: ▸ Detection principle, physics inputs ▸ Example experiments & results ▸ Outlook Uwe Oberlack ESIPAP 2016 2 Types of Evidences for Dark Matter ● Kinematic studies use luminous astrophysical objects to probe the gravitational potential of a massive environment, e.g.: ▸ Stars or gas clouds probing the gravitational potential of galaxies ▸ Galaxies or intergalactic gas probing the gravitational potential of galaxy clusters ● Gravitational lensing is an independent way to measure the total mass (profle) of a foreground object using the light of background sources (galaxies, active galactic nuclei). ● Comparison of mass profles with observed luminosity profles lead to a problem of missing mass, usually interpreted as evidence for Dark Matter. ● Measuring the geometry (curvature) of the universe, indicates a ”fat” universe with close to critical density. Comparison with luminous mass: → a major accounting problem! Including observations of the expansion history lead to the Standard Model of Cosmology: accounting defcit solved by ~68% Dark Energy, ~27% Dark Matter and <5% “regular” (baryonic) matter. ● Other lines of evidence probe properties of matter under the infuence of gravity: ▸ the equation of state of oscillating matter as observed through fuctuations of the Cosmic Microwave Background (acoustic peaks). -

![DARK MATTER and NEUTRINOS Arxiv:1711.10564V1 [Physics.Pop-Ph]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1574/dark-matter-and-neutrinos-arxiv-1711-10564v1-physics-pop-ph-391574.webp)

DARK MATTER and NEUTRINOS Arxiv:1711.10564V1 [Physics.Pop-Ph]

Physics Education 1 dateline DARK MATTER AND NEUTRINOS Gazal Sharma1, Anu2 and B. C. Chauhan3 Department of Physics & Astronomical Science School of Physical & Material Sciences Central University of Himachal Pradesh (CUHP) Dharamshala, Kangra (HP) INDIA-176215. [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] (Submitted 03-08-2015) Abstract The Keplerian distribution of velocities is not observed in the rotation of large scale structures, such as found in the rotation of spiral galaxies. The deviation from Keplerian distribution provides compelling evidence of the presence of non-luminous matter i.e. called dark matter. There are several astrophysical motivations for investigating the dark matter in and around the galaxy as halo. In this work we address various theoretical and experimental indications pointing towards the existence of this unknown form of matter. Amongst its constituents neutrino is one of the most prospective candidates. We know the neutrinos oscillate and have tiny masses, but there are also signatures for existence of heavy and light sterile neutrinos and possibility of their mixing. Altogether, the role of neutrinos is of great interests in cosmology and understanding dark matter. arXiv:1711.10564v1 [physics.pop-ph] 23 Nov 2017 1 Introduction revealed in 2013 that our Universe contains 68:3% of dark energy, 26:8% of dark matter, and only 4:9% of the Universe is known mat- As a human being the biggest surprise for us ter which includes all the stars, planetary sys- was, that the Universe in which we live in tems, galaxies, and interstellar gas etc.. This is mostly dark. -

Signs of Dark Matter May Point to Mirror Matter Candidate 27 April 2010, by Lisa Zyga

Signs of dark matter may point to mirror matter candidate 27 April 2010, by Lisa Zyga (PhysOrg.com) -- Dark matter, which contains the At first, mirror matter may sound a bit like antimatter "missing mass" that's needed to explain why (which is ordinary matter with an opposite charge). galaxies stay together, could take any number of In both theories, the number of known particles forms. The main possible candidates include would double. However, while antimatter interacts MACHOS and WIMPS, but there is no shortage of very strongly with ordinary matter, annihilating itself proposals. Rather, the biggest challenge is finding into photons, mirror matter would interact very some evidence that would support one or more of weakly with ordinary matter. For this reason, some these candidates. Currently, more than 30 physicists have speculated that mirror particles experiments are underway trying to detect a sign of could be candidates for dark matter. Even though dark matter. So far, only two experiments claim to mirror matter would produce light, we would not see have found signals, with the most recent it, and it would be very difficult to detect. observations coming just a month ago. Now, physicist Robert Foot from the University of However, mirror matter would not be impossible to Melbourne has shown that the results of these two detect, and Foot thinks that the DAMA experiment experiments can be simultaneously explained by and the CoGeNT experiment may have detected an intriguing dark matter candidate called mirror mirror matter. In DAMA, scientists observed a piece matter. of sodium iodide, which should generate a photon when struck by a dark matter particle. -

A Derivation of Modified Newtonian Dynamics

Journal of The Korean Astronomical Society http://dx.doi.org/10.5303/JKAS.2013.46.2.93 46: 93 ∼ 96, 2013 April ISSN:1225-4614 c 2013 The Korean Astronomical Society. All Rights Reserved. http://jkas.kas.org A DERIVATION OF MODIFIED NEWTONIAN DYNAMICS Sascha Trippe Department of Physics and Astronomy, Seoul National University, Seoul 151-742, Korea E-mail : [email protected] (Received February 14, 2013; Revised March 20, 2013; Accepted March 29, 2013) ABSTRACT Modified Newtonian Dynamics (MOND) is a possible solution for the missing mass problem in galac- tic dynamics; its predictions are in good agreement with observations in the limit of weak accelerations. However, MOND does not derive from a physical mechanism and does not make predictions on the transitional regime from Newtonian to modified dynamics; rather, empirical transition functions have to be constructed from the boundary conditions and comparisons with observations. I compare the formalism of classical MOND to the scaling law derived from a toy model of gravity based on virtual massive gravitons (the “graviton picture”) which I proposed recently. I conclude that MOND naturally derives from the “graviton picture” at least for the case of non-relativistic, highly symmetric dynamical systems. This suggests that – to first order – the “graviton picture” indeed provides a valid candidate for the physical mechanism behind MOND and gravity on galactic scales in general. Key words : Gravitation — Galaxies: kinematics and dynamics −10 −2 1. INTRODUCTION where x = ac/am, am ≈ 10 ms is Milgrom’s con- stant, and µ(x)isa transition function with the asymp- “ It is worth remembering that all of the discus- totic behavior µ(x) → 1 for x ≫ 1 and µ(x) → x for sion [on dark matter] so far has been based on x ≪ 1. -

Particle - Mirror Particle Oscillations: CP-Violation and Baryon Asymmetry

Particle - Mirror Particle Oscillations: CP-violation and Baryon Asymmetry Zurab Berezhiani Università di L’Aquila and LNGS, Italy 0 CPT at ICTP, Triest, 2-5 July 2008 n − n oscillations etc ... - p. 1/42 Alice & Mirror World Lewis Carroll, "Through the Looking-Glass" ‘Now, if you’ll only attend, Kitty, and not talk so much, I’ll tell you all my ideas about Looking-glass House. There’s the room you can see through the glass – that’s just the same ● Carrol’s Alice... ● Mirror World as our drawing-room, only the things go the other way... the books are something like our ● Mirror Particles ● Interactions books, only the words go the wrong way: I know that, because I’ve held up one of our books to ● B & L violation ● BBN demands the glass, and then they hold up one in the other room. I can see all of it – all but the bit just ● Present Cosmology ● Visible vs. Dark matter behind the fireplace. I do so wish I could see that bit! I want so to know whether they’ve a fire ● B vs. D – Fine Tuning demonstration ● Unification in the winter: you never can tell, you know, unless our fire smokes, and then smoke comes up ● Neutrino Mixing ● See-Saw in that room too – but that may be only pretence, just to make it look as if they had a fire... ● Leptogenesis: diagrams ● Leptogenesis: formulas ‘How would you like to leave in the Looking-glass House, Kitty? I wander if they’d give you milk ● Epochs ● Neutron mixing in there? But perhaps Looking-glass milk isn’t good to drink? Now we come to the passage: ● Neutron mixing ● Oscillation it’s very like our passage as far as you can see, only you know it may be quite on beyond. -

Glossary of Terms Absorption Line a Dark Line at a Particular Wavelength Superimposed Upon a Bright, Continuous Spectrum

Glossary of terms absorption line A dark line at a particular wavelength superimposed upon a bright, continuous spectrum. Such a spectral line can be formed when electromag- netic radiation, while travelling on its way to an observer, meets a substance; if that substance can absorb energy at that particular wavelength then the observer sees an absorption line. Compare with emission line. accretion disk A disk of gas or dust orbiting a massive object such as a star, a stellar-mass black hole or an active galactic nucleus. An accretion disk plays an important role in the formation of a planetary system around a young star. An accretion disk around a supermassive black hole is thought to be the key mecha- nism powering an active galactic nucleus. active galactic nucleus (agn) A compact region at the center of a galaxy that emits vast amounts of electromagnetic radiation and fast-moving jets of particles; an agn can outshine the rest of the galaxy despite being hardly larger in volume than the Solar System. Various classes of agn exist, including quasars and Seyfert galaxies, but in each case the energy is believed to be generated as matter accretes onto a supermassive black hole. adaptive optics A technique used by large ground-based optical telescopes to remove the blurring affects caused by Earth’s atmosphere. Light from a guide star is used as a calibration source; a complicated system of software and hardware then deforms a small mirror to correct for atmospheric distortions. The mirror shape changes more quickly than the atmosphere itself fluctuates. -

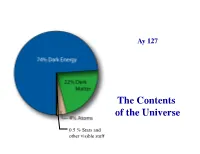

The Contents of the Universe

Ay 127! The Contents of the Universe 0.5 % Stars and other visible stuff Supernovae alone ⇒ Accelerating expansion ⇒ Λ > 0 CMB alone ⇒ Flat universe ⇒ Λ > 0 Any two of SN, CMB, LSS ⇒ Dark energy ~70% Also in agreement with the age estimates (globular clusters, nucleocosmochronology, white dwarfs) Today’s Best Guess Universe Age: Best fit CMB model - consistent with ages of oldest stars t0 =13.82 ± 0.05 Gyr Hubble constant: CMB + HST Key Project to -1 -1 measure Cepheid distances H0 = 69 km s Mpc € Density of ordinary matter: CMB + comparison of nucleosynthesis with Lyman-a Ωbaryon = 0.04 € forest deuterium measurement Density of all forms of matter: Cluster dark matter estimate CMB power spectrum 0.31 € Ωmatter = Cosmological constant: Supernova data, CMB evidence Ω = 0.69 for a flat universe plus a low € Λ matter density € The Component Densities at z ~ 0, in critical density units, assuming h ≈ 0.7 Total matter/energy density: Ω0,tot ≈ 1.00 From CMB, and consistent with SNe, LSS From local dynamics and LSS, and Matter density: Ω0,m ≈ 0.31 consistent with SNe, CMB From cosmic nucleosynthesis, Baryon density: Ω0,b ≈ 0.045 and independently from CMB Luminous baryon density: Ω0,lum ≈ 0.005 From the census of luminous matter (stars, gas) Since: Ω0,tot > Ω0,m > Ω0,b > Ω0,lum There is baryonic dark matter There is non-baryonic dark matter There is dark energy The Luminosity Density Integrate galaxy luminosity function (obtained from large redshift surveys) to obtain the mean luminosity density at z ~ 0 8 3 SDSS, r band: ρL = (1.8 ± 0.2) 10 h70 L/Mpc 8 3 2dFGRS, b band: ρL = (1.4 ± 0.2) 10 h70 L/Mpc Luminosity To Mass Typical (M/L) ratios in the B band along the Hubble sequence, within the luminous portions of galaxies, are ~ 4 - 5 M/L This includes some dark matter - for pure stellar populations, (M/L) ratios should be slightly lower. -

Modified Newtonian Dynamics, an Introductory Review

Modified Newtonian Dynamics, an Introductory Review Riccardo Scarpa European Southern Observatory, Chile E-mail [email protected] Abstract. By the time, in 1937, the Swiss astronomer Zwicky measured the velocity dispersion of the Coma cluster of galaxies, astronomers somehow got acquainted with the idea that the universe is filled by some kind of dark matter. After almost a century of investigations, we have learned two things about dark matter, (i) it has to be non-baryonic -- that is, made of something new that interact with normal matter only by gravitation-- and, (ii) that its effects are observed in -8 -2 stellar systems when and only when their internal acceleration of gravity falls below a fix value a0=1.2×10 cm s . Being completely decoupled dark and normal matter can mix in any ratio to form the objects we see in the universe, and indeed observations show the relative content of dark matter to vary dramatically from object to object. This is in open contrast with point (ii). In fact, there is no reason why normal and dark matter should conspire to mix in just the right way for the mass discrepancy to appear always below a fixed acceleration. This systematic, more than anything else, tells us we might be facing a failure of the law of gravity in the weak field limit rather then the effects of dark matter. Thus, in an attempt to avoid the need for dark matter many modifications of the law of gravity have been proposed in the past decades. The most successful – and the only one that survived observational tests -- is the Modified Newtonian Dynamics. -

Mirror Matter: Astrophysical Implications

Mirror Matter: Astrophysical implications Zurab Berezhiani Summary Mirror Matter: Astrophysical implications Introduction: Dark Matter from a Parallel World Chapter I: Neutrino - mirror neutrino mixings Zurab Berezhiani Chapter II: neutron { mirror University of L'Aquila and LNGS neutron mixing Chapter IV: n − n0 and Neutron Stars Quarks-2021 , 22-24 June 2021 Contents Mirror Matter: Astrophysical implications Zurab Berezhiani Summary Introduction: Dark Matter from 1 Introduction: Dark Matter from a Parallel World a Parallel World Chapter I: Neutrino - mirror neutrino mixings 2 Chapter I: Neutrino - mirror neutrino mixings Chapter II: neutron { mirror neutron mixing Chapter IV: n − n0 and 3 Chapter II: neutron { mirror neutron mixing Neutron Stars 4 Chapter IV: n n0 and Neutron Stars − Mirror Matter: Astrophysical implications Zurab Berezhiani Summary Introduction: Dark Matter from a Parallel World Introduction Chapter I: Neutrino - mirror neutrino mixings Chapter II: neutron { mirror neutron mixing Chapter IV: n − n0 and Everything can be explained by the Standard Model ! Neutron Stars ... but there should be more than one Standard Models Bright & Dark Sides of our Universe Mirror Matter: Ω 0 05 observable matter: electron, proton, neutron ! Astrophysical B : implications ' ΩD 0:25 dark matter: WIMP? axion? sterile ν? ... Zurab Berezhiani ' ΩΛ 0:70 dark energy: Λ-term? Quintessence? .... Summary ' 3 Introduction: ΩR < 10− relativistic fraction: relic photons and neutrinos Dark Matter from a Parallel World Matter { dark energy coincidence: Ω Ω 0 45, (Ω = Ω + Ω ) Chapter I: M = Λ : M D B Neutrino - mirror 3 ' ρΛ Const., ρM a− ; why ρM /ρΛ 1 { just Today? neutrino mixings ∼ ∼ ∼ Chapter II: Antrophic explanation: if not Today, then Yesterday or Tomorrow. -

Lecture 4: Dark Matter in Galaxies

LectureLecture 4:4: DarkDark MatterMatter inin GalaxiesGalaxies OutlineOutline WhatWhat isis darkdark matter?matter? HowHow muchmuch darkdark mattermatter isis therethere inin thethe Universe?Universe? EvidenceEvidence ofof darkdark mattermatter ViableViable darkdark mattermatter candidatescandidates TheThe coldcold darkdark mattermatter (CDM)(CDM) modelmodel ProblemsProblems withwith CDMCDM onon galacticgalactic scalesscales AlternativesAlternatives toto darkdark mattermatter WhatWhat isis DarkDark Matter?Matter? Dark Matter Luminous Matter FirstFirst detectiondetection ofof darkdark mattermatter FritzFritz ZwickyZwicky (1933):(1933): DarkDark mattermatter inin thethe ComaComa ClusterCluster HowHow MuchMuch DarkDark MatterMatter isis ThereThere inin TheThe Universe?Universe? ΩΩ == ρρ // ρρ Μ Μ c ~2% RecentRecent measurements:measurements: (Luminous) Ω ∼ 0.25, Ω ∼ 0.75 ΩΜ ∼ 0.25, Ω Λ ∼ 0.75 ΩΩ ∼∼ 0.0050.005 Lum ~98% (Dark) HowHow DoDo WeWe KnowKnow ThatThat itit Exists?Exists? CosmologicalCosmological ParametersParameters ++ InventoryInventory ofof LuminousLuminous materialmaterial DynamicsDynamics ofof galaxiesgalaxies DynamicsDynamics andand gasgas propertiesproperties ofof galaxygalaxy clustersclusters GravitationalGravitational LensingLensing DynamicsDynamics ofof GalaxiesGalaxies II Galaxy ≈ Stars + Gas + Dust + Supermassive Black Hole + Dark Matter DynamicsDynamics ofof GalaxiesGalaxies IIII Visible galaxy Observed Vrot Expected R R Dark matter halo Visible galaxy DynamicsDynamics ofof GalaxyGalaxy ClustersClusters Balance