ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: SHEATHING the SWORD

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mapping the Jihadist Threat: the War on Terror Since 9/11

Campbell • Darsie Mapping the Jihadist Threat A Report of the Aspen Strategy Group 06-016 imeless ideas and values,imeless ideas contemporary dialogue on and open-minded issues. t per understanding in a nonpartisanper understanding and non-ideological setting. f e o e he mission ofhe mission enlightened leadership, foster is to Institute Aspen the d n T io ciat e r p Through seminars, policy programs, initiatives, development and leadership conferences the Institute and its international partners seek to promote the pursuit of the pursuit partners and its international promote seek to the Institute and ground common the ap Mapping the Jihadist Threat: The War on Terror Since 9/11 A Report of the Aspen Strategy Group Kurt M. Campbell, Editor Willow Darsie, Editor u Co-Chairmen Joseph S. Nye, Jr. Brent Scowcroft To obtain additional copies of this report, please contact: The Aspen Institute Fulfillment Office P.O. Box 222 109 Houghton Lab Lane Queenstown, Maryland 21658 Phone: (410) 820-5338 Fax: (410) 827-9174 E-mail: [email protected] For all other inquiries, please contact: The Aspen Institute Aspen Strategy Group Suite 700 One Dupont Circle, NW Washington, DC 20036 Phone: (202) 736-5800 Fax: (202) 467-0790 Copyright © 2006 The Aspen Institute Published in the United States of America 2006 by The Aspen Institute All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 0-89843-456-4 Inv No.: 06-016 CONTENTS DISCUSSANTS AND GUEST EXPERTS . 1 AGENDA . 5 WORKSHOP SCENE SETTER AND DISCUSSION GUIDE Kurt M. Campbell Aspen Strategy Group Workshop August 5-10, 2005 . -

Considering the Creation of a Domestic Intelligence Agency in the United States

HOMELAND SECURITY PROGRAM and the INTELLIGENCE POLICY CENTER THE ARTS This PDF document was made available CHILD POLICY from www.rand.org as a public service of CIVIL JUSTICE the RAND Corporation. EDUCATION ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT Jump down to document6 HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit NATIONAL SECURITY research organization providing POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY objective analysis and effective SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY solutions that address the challenges SUBSTANCE ABUSE facing the public and private sectors TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY around the world. TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE Support RAND WORKFORCE AND WORKPLACE Purchase this document Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore the RAND Homeland Security Program RAND Intelligence Policy Center View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND PDFs to a non-RAND Web site is prohibited. RAND PDFs are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This product is part of the RAND Corporation monograph series. RAND monographs present major research findings that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND mono- graphs undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for research quality and objectivity. -

Extraordinary Rendition in U.S. Counterterrorism Policy: the Impact on Transatlantic Relations

EXTRAORDINARY RENDITION IN U.S. COUNTERTERRORISM POLICY: THE IMPACT ON TRANSATLANTIC RELATIONS JOINT HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS, HUMAN RIGHTS, AND OVERSIGHT AND THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON EUROPE OF THE COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION APRIL 17, 2007 Serial No. 110–28 Printed for the use of the Committee on Foreign Affairs ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.foreignaffairs.house.gov/ U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 34–712PDF WASHINGTON : 2007 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS TOM LANTOS, California, Chairman HOWARD L. BERMAN, California ILEANA ROS-LEHTINEN, Florida GARY L. ACKERMAN, New York CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH, New Jersey ENI F.H. FALEOMAVAEGA, American DAN BURTON, Indiana Samoa ELTON GALLEGLY, California DONALD M. PAYNE, New Jersey DANA ROHRABACHER, California BRAD SHERMAN, California DONALD A. MANZULLO, Illinois ROBERT WEXLER, Florida EDWARD R. ROYCE, California ELIOT L. ENGEL, New York STEVE CHABOT, Ohio BILL DELAHUNT, Massachusetts THOMAS G. TANCREDO, Colorado GREGORY W. MEEKS, New York RON PAUL, Texas DIANE E. WATSON, California JEFF FLAKE, Arizona ADAM SMITH, Washington JO ANN DAVIS, Virginia RUSS CARNAHAN, Missouri MIKE PENCE, Indiana JOHN S. TANNER, Tennessee THADDEUS G. MCCOTTER, Michigan LYNN C. WOOLSEY, California JOE WILSON, South Carolina SHEILA JACKSON LEE, Texas JOHN BOOZMAN, Arkansas RUBE´ N HINOJOSA, Texas J. GRESHAM BARRETT, South Carolina DAVID WU, Oregon CONNIE MACK, Florida BRAD MILLER, North Carolina JEFF FORTENBERRY, Nebraska LINDA T. -

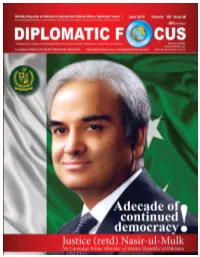

June 2018 Volume 09 Issue 06 “Publishing from Pakistan, United Kingdom/EU & Will Be Soon from UAE ”

June 2018 Volume 09 Issue 06 “Publishing from Pakistan, United Kingdom/EU & will be soon from UAE ” 09 10 19 31 09 Close and fraternal relations between Turkey is playing a very positive role towards the resolution Pakistan & Turkey are the guarantee of of different international issues. Turkey has dealt with the stability and prosperity in the region: Middle East crisis and especially the issue of refugees in a very positive manner, President Mamnoon Hussain 10 7th Caretaker PM of Pakistan Former Former CJP Nasirul Mulk was born on August 17, 1950 in CJP Nasirul Mulk Mingora, Swat. He completed his degree of Bar-at-Law from Inner Temple London and was called to the Bar in 1977. 19 President Emomali Rahmon expressed The sides discussed the issues of strengthening bilateral satisfaction over the friendly relations and cooperation in combating terrorism, extremism, drug multifaceted cooperation between production and transnational crime. Tajikistan & Pakistan 31 Colorful Cultural Exchanges between China and Pakistan are not only friendly neighbors, but also China and Pakistan two major ancient civilizations that have maintained close ties in cultural exchanges and mutual learning. The Royal wedding 2018 Since announcing their engagement in 13 November 2017, the world has been preparing for Prince Harry and Meghan Markle’s royal wedding. The Duke and Duchess of Sussex begin their first day as a married couple following an emotional ceremony that captivated the nation and a night spent partying with close family and friends. 06 Diplomatic Focus June 2018 RBI Mediaminds Contents Group of Publications Electronic & Print Media Production House 09 Pakistan & Turkey Close and fraternal relations …: President Mamnoon Hussain 10 7th Caretaker PM of Pakistan Former CJP Nasirul Mulk 12 The Royal wedding2018 Group Chairman/CEO: Mian Fazal Elahi 14 Pakistan & Saudi Arabia are linked through deep historic, religious and cultural Chief Editor: Mian Akhtar Hussain relations Patron in Chief: Mr. -

The Crisis of Press Freedom and Journalist Safety in Pakistan

A state of denial The crisis of press freedom and journalist safety in Pakistan IFJ-PFUJ International Mission for Press Freedom and Journalist Safety in Pakistan February 22-25, 2007 A state of denial: the crisis of press freedom and journalist safety in Pakistan A state of denial: the crisis of press freedom and journalist safety in Pakistan Delegation report of IFJ-PFUJ International Mission for Press Freedom and Journalist Safety in Pakistan February 22-25, 2007 Published by: International Federation of Journalists Authors: Chris Morley, Maheen A. Rashdi, Iqbal Khattak Editors: Maheen A. Rashdi and Emma Walters Thanks to: Mazhar Abbas, Tahir Rathor and all PFUJ, IFJ-PFUJ Mission Members (Bharat Bhushan, Sunanda Deshapriya, Iqbal Khattak, Chris Morley, Christopher Warren), Matiullah Jan from Intermedia, Katie Nguyen, Laxmi Murthy. Design by: Louise Summerton, Gadfly Media Photographs by: Sunanda Deshapriya, Iqbal Khattak, Geo TV, Inp., REUTERS, The News International & AFP Photo Cover Photo: The Islamabad police storming the Geo News TV offices on March 16, 2007. Published in Australia by IFJ Asia-Pacific No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form without the written permission of the publisher. The contents of this book are copyrighted and the rights to the use of contributions rest with the authors themselves. 2 A state of denial: the crisis of press freedom and journalist safety in Pakistan INTRODUCTION The Pakistan media is facing twin crises of press freedom and of journalist safety. Nineteen journalists are believed to have been murdered since 2000, with four killed in just the past year. Numerous others have been attacked, assaulted and arrested during this time. -

August 2018 Volume 09 Issue 08 Promoting Bilateral Relations | Current Affairs | Trade & Economic Affairs | Education | Technology | Culture & Tourism ABC Certified

Monthly Magazine on National & International Political Affairs, Diplomatic Issues August 2018 Volume 09 Issue 08 Promoting Bilateral Relations | Current Affairs | Trade & Economic Affairs | Education | Technology | Culture & Tourism ABC Certified “Publishing from Pakistan, United Kingdom/EU & will be soon from UAE , Central Africa, Central Asia & Asia Pacific” Member APNS Central Media List A Largest, Widely Circulated Diplomatic Magazine | www.diplomaticfocus.org | www.diplomaticfocus-uk.com | Member Diplomatic Council /diplomaticfocusofficial /DFocusOfficial Congratulations! PAKISTAN 14th AugustDAY INDEPENDENCE Hot Seat Waiting with number of nerve-wracking challenges! FromIMRAN cricket star to front-runner KHAN in General Elections 2018 00 Diplomatic Focus April 2018 August 2018 Volume 09 Issue 08 “Publishing from Pakistan, United Kingdom/EU & will be soon from UAE ” 08 14 22 54 08 From cricket star to frontrunner in Election Khan made history in General Election 2018 when he Pakistan 2018: IMRAN KHAN simultaneously elected as Member of Parliament from five constituencies spread over different parts of country. And his party PTI, after preliminary results showed decisively ahead in election 2018. It is a sign that Mr. Khan may be soon become Prime Minister of Islamic Republic of Pakistan. 14 Elections were satisfactory: EU observers The EU EOM to Pakistan expressed satisfaction over overall conduct of the general elections, saying efforts of the Election Commission of Pakistan (ECP) were impressive and appreciable. But the mission further said “there were several legal provisions aimed at ensuring a level playing field, there was a lack of equality of opportunity” provided to the contesting parties. 22 Recep Tayyip Erdogan sworn in Turkey has officially switched to an executive presidency after New government system begins in Turkey President Recep Tayyip Erdogan took the oath of office on July 9. -

Download Article

tHe ABU oMAr CAse And “eXtrAordinAry rendition” Caterina Mazza Abstract: In 2003 Hassan Mustafa Osama Nasr (known as Abu Omar), an Egyptian national with a recognised refugee status in Italy, was been illegally arrested by CIA agents operating on Italian territory. After the abduction he was been transferred to Egypt where he was in- terrogated and tortured for more than one year. The story of the Milan Imam is one of the several cases of “extraordinary renditions” imple- mented by the CIA in cooperation with both European and Middle- Eastern states in order to overwhelm the al-Qaeda organisation. This article analyses the particular vicissitude of Abu Omar, considered as a case study, and to face different issues linked to the more general phe- nomenon of extra-legal renditions thought as a fundamental element of US counter-terrorism strategies. Keywords: extra-legal detention, covert action, torture, counter- terrorism, CIA Introduction The story of Abu Omar is one of many cases which the Com- mission of Inquiry – headed by Dick Marty (a senator within the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe) – has investi- gated in relation to the “extraordinary rendition” programme im- plemented by the CIA as a counter-measure against the al-Qaeda organisation. The programme consists of secret and illegal arrests made by the police or by intelligence agents of both European and Middle-Eastern countries that cooperate with the US handing over individuals suspected of being involved in terrorist activities to the CIA. After their “arrest,” suspects are sent to states in which the use of torture is common such as Egypt, Morocco, Syria, Jor- dan, Uzbekistan, Somalia, Ethiopia.1 The practice of rendition, in- tensified over the course of just a few years, is one of the decisive and determining elements of the counter-terrorism strategy planned 134 and approved by the Bush Administration in the aftermath of the 11 September 2001 attacks. -

OPEN SOURCE INFORMATION the Missing Dimension of Intelligence CSIS Repo

T R OPEN SOURCE INFORMATION The Missing Dimension of Intelligence CSIS REPO A Report of the CSIS Transnational Threats Project Authors Arnaud de Borchgrave Thomas Sanderson John MacGaffin ISBN-13: 978-0-89206-483-0 ISBN-10: 0-89206-483-8 THE CENTER FOR STRATEGIC & INTERNATIONAL STUDIES 1800 K Street, NW • Washington, DC 20006 Telephone: (202) 887-0200 • Fax: (202) 775-3199 E-mail: books©csis.org • Web site: http://www.csis.org/ Ë|xHSKITCy064830zv*:+:!:+:! March 2006 OPEN SOURCE INFORMATION The Missing Dimension of Intelligence A Report of the CSIS Transnational Threats Project Authors Arnaud de Borchgrave Thomas Sanderson John MacGaffin March 2006 About CSIS The Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) seeks to advance global security and prosperity in an era of economic and political transformation by providing strategic insights and practical policy solutions to decisionmakers. CSIS serves as a strategic planning partner for the government by conducting research and analysis and developing policy initiatives that look into the future and anticipate change. Our more than 25 programs are organized around three themes: Defense and Security Policy—With one of the most comprehensive programs on U.S. defense policy and international security, CSIS proposes reforms to U.S. defense organization, defense policy, and the defense industrial and technology base. Other CSIS programs offer solutions to the challenges of proliferation, transnational terrorism, homeland security, and post-conflict reconstruction. Global Challenges—With programs on demographics and population, energy security, global health, technology, and the international financial and economic system, CSIS addresses the new drivers of risk and opportunity on the world stage. -

April 2018 Volume 09 Issue 04 “Publishing from Pakistan, United Kingdom/EU & Will Be Soon from UAE ”

April 2018 Volume 09 Issue 04 “Publishing from Pakistan, United Kingdom/EU & will be soon from UAE ” 10 22 30 34 10 President of Sri Lanka to play his role for His Excellency Maithripala Sirisena, President of the early convening of the SAARC Summit in Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka visited Pakistan Islamabad on the occasion of Pakistan Day. He was the guest of honour at the Pakistan Day parade on 23rd March 2018. 22 Economic Cooperation between Russia & On May 1, 2018 Russia and Pakistan are celebrating the 70th Pakistan Achievements and Challenges anniversary of establishing bilateral diplomatic relations. Our countries are bound by strong ties of friendship based on mutual respect and partnership, desire for multi-faceted and equal cooperation. 30 Peace with India is possible only after Pakistan has eliminated sanctuaries of all terrorists groups Resolving Kashmir issue: DG ISPR including the Haqqani Network from its soil through a wellthought- out military campaign, said a top military official. 34 Pakistanis a land of Progress & While Pakistan is exploring and expediting various avenues of Opportunities… development growth, it has been receiving consistent support from United Nations. 42 78th Pakistan Resolution Day Celebrated 42 The National Day of Pakistan is celebrated every year on the 23rd March to commemorate the outstanding achievement of the Muslims of Sub-Continent who passed the historic “Pakistan Resolution” on this day at Lahore in 1940 which culminated in creation of Pakistan after 7 years. 06 Diplomatic Focus April 2018 RBI Mediaminds Contents Group of Publications Electronic & Print Media Production House 09 New Envoys Presented Credentials to President Mamnoon Hussain Group Chairman/CEO: Mian Fazal Elahi 10 President of Sri Lanka to play his role for early convening of the SAARC Chief Editor: Mian Akhtar Hussain Summit in Islamabad Patron in Chief: Mr. -

The Jihadist Threat in France CLARA BEYLER

The Jihadist Threat in France CLARA BEYLER INCE THE MADRID AND LONDON BOMBINGS, Europeans elsewhere— fearful that they may become the next targets of Islamist terrorism— are finally beginning to face the consequences of the long, unchecked Sgrowth of radical Islam on their continent. The July bombings in London, while having the distinction of being the first suicide attacks in Western Eu- rope, were not the first time terrorists targeted a major European subway system. Ten years ago, a group linked to the Algerian Armed Islamic Group (Groupe Islamique Armé—GIA) unleashed a series of bombings on the Paris metro system. Since 1996, however, France has successfully avoided any ma- jor attack on its soil by an extremist Muslim group. This is due not to any lack of terrorist attempts—(only last September, France arrested nine members of a radical Islamist cell planning to attack the metro system)—but rather to the efficiency of the French counterterrorist services.1 France is now home to between five to six million Muslims—the sec- ond largest religious group in France, and the largest Muslim population in any Western European country.2 The majority of this very diverse population practices and believes in an apolitical, nonviolent Islam.3 A minority of them, however, are extremists. Islamist groups are actively operating in France to- day, spreading radical ideology and recruiting for future terrorist attacks on French soil and abroad. The purpose of this paper is to provide an overview of France’s Islamist groups, the evolving threats they have posed and continue to pose to French society, and the response of the French authorities to these threats. -

TERRORISM FOCUS Volume VI G Issue 6 G February 25, 2009 in THIS ISSUE

The Jamestown Foundation TerrorismFocus Volume VI u Issue 6 u February 25, 2009 TERRORISM FOCUS Volume VI g Issue 6 g February 25, 2009 IN THIS ISSUE: * BRIEFS.....................................................................................................................................1 * Jihadis Speculate on Secret Cooperation between Iran and al-Qaeda...................3 * Rising Arab-Kurdish Tensions over Kirkuk Will Complicate U.S. Withdrawal from Iraq .............................................................................................................................4 * Polish-Born Muslim Convert Sentenced for Leading Role in Tunisian Synagogue Bombing ....................................................................................................................6 * Government Forces Overrun Tuareg Rebel Camps in Northern Mali......................8 AL-QAEDA AND OIL FACILITIES IN THE SHADOW OF THE GLOBAL ECONOMIC For comments or questions about our CRISIS publications, please send an email to [email protected], or contact us at: 1111 16th St., NW, Suite #320 Washington, DC 20036 By Murad Batal al-Shishani T: (202) 483-8888 F: (202) 483-8337 http://www.jamestown.org In its latest issue, Bahraini weekly business magazine The Gulf reported that Middle East oil companies are spending billions of dollars on security every year and the cost is rising fast, with Saudi Arabia alone expected The Terrorism Focus is a fortnightly complement to Jamestown’s Terrorism to spend $14 billion over the next six years (The Gulf, February 21-27). Monitor, providing detailed and timely analysis of developments for policymakers and analysts, informing In the shadow of the global economic crisis—a time when oil prices them of the latest trends in the War on have seen a great decrease over the last couple of months—it seems Terror. that the threat of targeting oil interests by al-Qaeda and affiliated Salafi- Jihadi groups is currently on the rise. -

Spy Lingo — a Secret Eye

A Secret Eye SpyLingo A Compendium Of Terms Used In The Intelligence Trade — July 2019 — A Secret Eye . blog PUBLISHER'S NOTICE: Although the authors and publisher have made every eort to ensure that the information in this book was correct at press time, the authors and publisher do not assume and hereby disclaim any liability to any party for any loss, damage, or disruption caused by errors or omissions, whether such errors or omissions result from negligence, TEXTUAL CONTENT: Textual Content can be reproduced for all non-commercial accident, or any other cause. purposes as long as you provide attribution to the author / and original source where available. CONSUMER NOTICE: You should assume that the author of this document has an aliate relationship and/or another material connection to the providers of goods and services mentioned in this report THIRD PARTY COPYRIGHT: and may be compensated when you purchase from a To the extent that copyright subsists in a third party it provider. remains with the original owner. Content compiled and adapted by: Vincent Hardy & J-F Bouchard © Copyright 9218-0082 Qc Inc July 2019 — Spy Lingo — A Secret Eye Table Of Contents INTRODUCTION 4 ALPHA 5 Ab - Ai 5 Al - As 6 Au - Av 7 Bravo 8 Ba - Bl 8 Bl - Bre 9 Bri - Bu 10 CHARLIE 11 C3 - Can 11 Car - Chi 12 Cho - Cl 13 Cn - Com 14 Comp - Cou 15 Cov 16 Cu 17 DELTA 18 Da - De 18 De - Di 19 Di - Dru 20 Dry - Dz 21 Echo 22 Ea - Ex 22 Ey 23 FOXTROT 24 Fa - Fi 24 Fl - For 25 Fou - Fu 26 GOLF 27 Ga - Go 27 Gr - Gu 28 HOTEL 29 Ha - Hoo 29 Hou - Hv 30 INDIA 31 Ia