True World Income Distribution, 1988 and 1993: First Calculation Based on Household Surveys Alone*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download (743Kb)

American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 2018, 10(2): 234–256 https://doi.org/10.1257/app.20150365 Education and Mortality: Evidence from a Social Experiment† By Costas Meghir, Mårten Palme, and Emilia Simeonova* We examine the effects on mortality and health due to a major Swedish educational reform that increased the years of compulsory schooling. Using the gradual phase-in of the reform between 1949 and 1962 across municipalities, we estimate insignificant effects of the reform on mortality in the affected cohort. From the confi- dence intervals, we can rule out effects larger than 1–1.4 months of increased life expectancy. We find no significant impacts on mortality for individuals of low socioeconomic status backgrounds, on deaths that are more likely to be affected by behavior, on hospitalizations, and consumption of prescribed drugs. JEL H52, I12, I21, I28 ( ) he strong correlation between socioeconomic status SES and health is one ( ) Tof the most recognized and studied in the social sciences. Economists have pointed at differences in resources, preferences, and knowledge associated with dif- ferent SES groups as possible explanations see, e.g., Grossman 2006 for an over- ( view . However, a causal link between any of these factors and later life health is ) hard to demonstrate, and the relative importance of different contributing factors is far from clear. A series of studies e.g., Lleras-Muney 2005, Oreopoulos 2006, Clark ( and Royer 2013, Lager and Torssander 2012, and summaries in Mazumder 2008 and 2012 , use regional differences in compulsory schooling laws or changes in national ) legislations on compulsory schooling as a source of exogenous variation in edu- cational attainment in order to identify a causal effect of education on health. -

Is the Greek Crisis One of Supply Or Demand?

YANNIS M. IOANNIDES Tufts University CHRISTOPHER A. PISSARIDES London School of Economics Is the Greek Crisis One of Supply or Demand? ABSTRACT Greece’s “supply” problems have been present since its acces- sion to the European Union in 1981; the “demand” problems caused by austerity and wage cuts have compounded the structural problems. This paper discusses the severity of the demand contraction, examines product market reforms, many of which have not been implemented, and their potential impact on com- petitiveness and the economy, and labor market reforms, many of which have been implemented but due to their timing have contributed to the collapse of demand. The paper argues in favor of eurozone-wide policies that would help Greece recover and of linking reforms with debt relief. reece joined the European Union (EU) in 1981 largely on politi- Gcal grounds to protect democracy after the malfunctioning political regimes that followed the civil war in 1949 and the disastrous military dictatorship of the years 1967–74. Not much attention was paid to the economy and its ability to withstand competition from economically more advanced European nations. A similar blind eye was turned to the economy when the country applied for membership in the euro area in 1999, becom- ing a full member in 2001. It is now blatantly obvious that the country was not in a position to compete and prosper in the European Union’s single market or in the euro area. A myriad of restrictions on free trade had been introduced piecemeal after 1949, with the pretext of protecting those who fought for democracy. -

Parent Engagement Ca...Oddlers' Skills Development

2/19/2020 Not just for play: parent engagement can boost toddlers’ skills development | YaleNews YaleNews Not just for play: parent engagement can boost toddlers’ skills development By Lisa Qian 14, 2020 A study involving low-income families in central Colombia found that toddlers whose parents engaged them in play with books and toys made of discarded household materials showed significant improvements in their cognitive and socio- emotional skills Encouraging low-income families to stimulate their toddlers with play and involve them in household activities can improve the children's cognitive and socio-emotional skills development, Yale researchers found in a new study of an early-childhood intervention designed for families in central Colombia. The study, published last month in the American Economic Review (https://www.aeaweb.org/articles? id=10.1257/aer.20150183&within%5Btitle%5D=on&within%5Babstract%5D=on&within%5Bauthor%5D=on&journal=1&q=parental+&from=j) , is one of the first to develop a model for understanding how early childhood interventions among the poor change parental behavior and thus affect the cognitive development of their children. “What the results emphasize is that shifting parental behavior towards more engagement with the child is very important for children in low-income environments,” said Yale economist Costas Meghir https://news.yale.edu/2020/02/14/not-just-play-parent-engagement-can-boost-toddlers-skills-development 1/3 2/19/2020 Not just for play: parent engagement can boost toddlers’ skills development | YaleNews (https://economics.yale.edu/people/faculty/costas-meghir) , a co-author of the paper. He noted that the fundamental aim of the research is to identify ways to prevent poverty from being passed down from one generation to the next by ensuring children develop to their full potential. -

Econ792 Reading 2020.Pdf

Economics 792: Labour Economics Provisional Outline, Spring 2020 This course will cover a number of topics in labour economics. Guidance on readings will be given in the lectures. There will be a number of problem sets throughout the course (where group work is encouraged), presentations, referee reports, and a research paper/proposal. These, together with class participation, will determine your final grade. The research paper will be optional. Students not submit- ting a paper will receive a lower grade. Small group work may be permitted on the research paper with the instructors approval, although all students must make substantive contributions to any paper. Labour Supply Facts Richard Blundell, Antoine Bozio, and Guy Laroque. Labor supply and the extensive margin. American Economic Review, 101(3):482–86, May 2011. Richard Blundell, Antoine Bozio, and Guy Laroque. Extensive and Intensive Margins of Labour Supply: Work and Working Hours in the US, the UK and France. Fiscal Studies, 34(1):1–29, 2013. Static Labour Supply Sören Blomquist and Whitney Newey. Nonparametric estimation with nonlinear budget sets. Econometrica, 70(6):2455–2480, 2002. Richard Blundell and Thomas Macurdy. Labor supply: A Review of Alternative Approaches. In Orley C. Ashenfelter and David Card, editors, Handbook of Labor Economics, volume 3, Part 1 of Handbook of Labor Economics, pages 1559–1695. Elsevier, 1999. Pierre A. Cahuc and André A. Zylberberg. Labor Economics. Mit Press, 2004. John F. Cogan. Fixed Costs and Labor Supply. Econometrica, 49(4):pp. 945–963, 1981. Jerry A. Hausman. The Econometrics of Nonlinear Budget Sets. Econometrica, 53(6):pp. 1255– 1282, 1985. -

The Use of Structural Models in Econometrics

Journal of Economic Perspectives—Volume 31, Number 2—Spring 2017—Pages 33–58 The Use of Structural Models in Econometrics Hamish Low and Costas Meghir he aim of this paper is to discuss the role of structural economic models in empirical analysis and policy design. This approach offers some valuable T payoffs, but also imposes some costs. Structural economic models focus on distinguishing clearly between the objec- tive function of the economic agents and their opportunity sets as defined by the economic environment. The key features of such an approach at its best are a tight connection with a theoretical framework alongside a clear link with the data that will allow one to understand how the model is identified. The set of assumptions under which the model inferences are valid should be clear: indeed, the clarity of the assumptions is what gives value to structural models. The central payoff of a structural econometric model is that it allows an empir- ical researcher to go beyond the conclusions of a more conventional empirical study that provides reduced-form causal relationships. Structural models define how outcomes relate to preferences and to relevant factors in the economic envi- ronment, identifying mechanisms that determine outcomes. Beyond this, they ■ Hamish Low is Professor of Economics, Cambridge University, Cambridge, United Kingdom, and Cambridge INET and Research Fellow, Institute for Fiscal Studies, London, United Kingdom. Costas Meghir is the Douglas A. Warner III Professor of Economics, Yale Univer- sity, New Haven, Connecticut; International Research Associate, Institute for Fiscal Studies, London, United Kingdom; Research Fellow, Institute of Labor Economics (IZA), Bonn, Germany; and Research Associate, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, Massachusetts. -

Syllabus for Lectures by Orazio Attanasio Part I the Production Function of Human Capital in Early Years

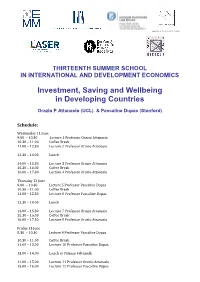

UNIVERSITA’ DEGLI STUDI DI TORINO THIRTEENTH SUMMER SCHOOL IN INTERNATIONAL AND DEVELOPMENT ECONOMICS Investment, Saving and Wellbeing in Developing Countries Orazio P Attanasio (UCL) & Pascaline Dupas (Stanford) Schedule: Wednesday 11 June 9.00 – 10.30 Lecture 1 Professor Orazio Attanasio 10.30 – 11.00 Coffee Break 11.00 – 12.30 Lecture 2 Professor Orazio Attanasio 12.30 – 14.00 Lunch 14.00 – 15.30 Lecture 3 Professor Orazio Attanasio 15.30 – 16.00 Coffee Break 16.00 – 17.30 Lecture 4 Professor Orazio Attanasio Thursday 12 June 9.00 – 10.30 Lecture 5 Professor Pascaline Dupas 10.30 – 11.00 Coffee Break 11.00 – 12.30 Lecture 6 Professor Pascaline Dupas 12.30 – 14.00 Lunch 14.00 – 15.30 Lecture 7 Professor Orazio Attanasio 15.30 – 16.00 Coffee Break 16.00 – 17.30 Lecture 8 Professor Orazio Attanasio Friday 13 June 8.30 – 10.30 Lecture 9 Professor Pascaline Dupas 10.30 – 11.00 Coffee Break 11.00 – 13.00 Lecture 10 Professor Pascaline Dupas 13.00 – 14.00 Lunch at Palazzo Feltrinelli 14.00 – 15.00 Lecture 11 Professor Orazio Attanasio 15.00 – 16.00 Lecture 12 Professor Pascaline Dupas Draft Syllabus for lectures by Orazio Attanasio Part I The production function of human capital in early years. Lecture 1, June 11 9:00-10:30 (90 minutes) 1.1 Evidence on human capital accumulation 1.1.1 The Socio Economic Gap in HK in early years in developing countries. 1.1.2 Interventions: community nurseries 1.1.3 Interventions: stimulations 1.1.3.1 The Jamaica Study 1.1.3.2 The Colombia Study Lecture 2, June 11:00-12:30 (90 minutes) 1.2 Models of accumulation of human capital: 1.2.1 The production function of human capital 1.2.2 Investment in human capital 1.2.3 Constraints to the accumulation of human capital. -

Three Essays in the Economics of Education Oswald Koussihouede

Three Essays in the Economics of Education Oswald Koussihouede To cite this version: Oswald Koussihouede. Three Essays in the Economics of Education. Economics and Finance. Uni- versité Gaston Berger, 2015. English. tel-01150504v2 HAL Id: tel-01150504 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-01150504v2 Submitted on 13 May 2015 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Copyright Université Gaston Berger Ecole Doctorale des Sciences de l’Homme et de la Société Unité de Formation et de Recherche en Sciences Economiques et de Gestion Three Essays in the Economics of Education Thèse présentée et soutenue publiquement le 13 Mars 2015 Pour l’obtention du grade de Docteur en sciences économiques Par: Oswald Koussihouèdé Jury: Mouhamadou Fall, Président, Université Gaston Berger, Sénégal Tanguy Bernard, Rapporteur, Université de Bordeaux, France Christian Monseur, Rapporteur, Université de Liège, Belgique Costas Meghir, Encadreur, Université Yale, Etats-Unis Adama Diaw, co-Encadreur, Université Gaston Berger, Sénégal L’Université Gaston Berger n’entend donner aucune approbation ni impro- bation aux opinions émises dans cette thèse. Ces opinions doivent être con- sidérées comme propres à leur(s) auteur(s). ii To Rachel-Sylviane, Emmanuelle and Théana, iii Acknowledgments I would like to acknowledge everyone who made this project possible. -

Decentralizing Education Resources: School Grants in Senegal

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES DECENTRALIZING EDUCATION RESOURCES: SCHOOL GRANTS IN SENEGAL Pedro Carneiro Oswald Koussihouèdé Nathalie Lahire Costas Meghir Corina Mommaerts Working Paper 21063 http://www.nber.org/papers/w21063 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 April 2015 Financial support was provided by the Education Program Development Fund (EPDF) of the World Bank. Pedro Carneiro thanks the financial support from the Economic and Social Research Council for the ESRC Centre for Microdata Methods and Practice (grant reference RES-589-28-0001), the support of the European Research Council through ERC-2009-StG-240910 and ERC-2009-AdG-249612. Costas Meghir thanks the ISPS and the Cowles foundation at Yale for financial assistance. Corina Mommaerts thanks the NSF Graduate Research Fellowship for support. All errors and views are ours alone and do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of the World Bank, the funding bodies or those commenting on the paper. This RCT was registered in the American Economic Association Registry for randomized control trials under Trial number 671. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer- reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2015 by Pedro Carneiro, Oswald Koussihouèdé, Nathalie Lahire, Costas Meghir, and Corina Mommaerts. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. -

Download Paper

Toward an Ethical Experiment∗ Yusuke Naritay June 11, 2018 Abstract Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs) enroll hundreds of millions of subjects and in- volve many human lives. To improve subjects' welfare, I propose an alternative design of RCTs. This design (1) produces a Pareto efficient allocation of treatment assignment probabilities, (2) is asymptotically incentive compatible for preference elicitation, and (3) unbiasedly estimates any causal effect estimable with standard RCTs. I quantify these properties by applying my proposal to a water cleaning experiment in Kenya (Kremer et al., 2011). Compared to standard RCTs, my design substantially improves subjects' predicted well-being while reaching similar treatment effect estimates with similar precision. Keywords: Research Ethics, Clinical Trial, Social Experiment, A/B Test, Market De- sign, Causal Inference, Development Economics, Spring Protection, Discrete Choice ∗I am grateful to Dean Karlan for a conversation that inspired this project; Joseph Moon for industrial and institutional input; Jason Abaluck, Josh Angrist, Tim Armstrong, Sylvain Chassang, Naoki Egami, Pe- ter Hull, Costas Meghir, Bobby Pakzad-Hurson, Amanda Kowalski, Michael Kremer, Kritika Narula, Rohini Pande, Parag Pathak, Mark Rosenzweig, Jesse Shapiro, Joseph Shapiro, Suk Joon Son, Seiki Tanaka, Kosuke Uetake, and Glen Weyl for criticisms and encouragement; seminar participants at Chicago, Columbia, Wis- consin, Tokyo, Oxford, Microsoft, AEA, RIKEN Center for Advanced Intelligence Project, Brown, NBER, Illinois, Yale, Hitotsubashi, European Summer Symposium in Economic Theory on \An Economic Per- spective on the Design and Analysis of Experiments," CyberAgent, Kyoto, International Conference on Experimental Methods in Economics. I received helpful research assistance from Soumitra Shukla, Jaehee Song, Mizuhiro Suzuki, Devansh Tandon, Lydia Wickard, and especially Qiwei He, Esther Issever, Zaiwei Liu, Vincent Tanutama, and Kohei Yata. -

Do Taxpayers Bunch at Kink Points?† 180 I

American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 2 (August 2010): 180–212 http://www.aeaweb.org/articles.php?doi 10.1257/pol.2.3.180 = Contents Do Taxpayers Bunch at Kink Points?† 180 I. Model, Data, and Methodology 183 A. Standard Model and Small Kink Analysis 183 † B. Empirical Estimation of the Elasticity using Bunching 185 Do Taxpayers Bunch at Kink Points? C. Data and Graphical Methodology 189 II. EITC Empirical Results 189 A. Graphical Evidence 190 By Emmanuel Saez* B. Elasticity Estimation 193 C. Interpretation: A Model of Tax Reporting 196 III. Federal Income Tax Empirical Results 200 This paper uses tax return data to analyze bunching at the kink points A. Background on Federal Income Tax Computation 200 B. Bunching Evidence around the First Kink Point from 1960–1972 202 of the US income tax schedule. We estimate the compensated elas- ticity of reported income with respect to one minus the marginal C. Bunching Evidence from 1988–2004 206 ( ) D. Elasticity Estimates 210 tax rate using bunching evidence. We find clear evidence of bunch- IV. Conclusion 210 References 211 ing around the first kink point of the Earned Income Tax Credit but concentrated solely among the self-employed. A simple tax evasion model can account for those results. We find evidence of bunching at the threshold of the first income tax bracket where tax liability starts but no evidence of bunching at any other kink point. JEL H23, H24, H26 ( ) large body of empirical work in labor and public economics analyzes the A behavioral response of earnings to taxes and transfers using the standard static model where agents choose to supply hours of work until the marginal disutility of work equals marginal utility of disposable net-of-tax income.1 This model, which ( ) from now on we call the standard model, predicts that, if individual preferences are convex and smoothly distributed in the population, we should observe bunching of individuals at convex kink points of the budget set. -

The Case of School and Neighborhood Effects

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES GROUP-AVERAGE OBSERVABLES AS CONTROLS FOR SORTING ON UNOBSERVABLES WHEN ESTIMATING GROUP TREATMENT EFFECTS: THE CASE OF SCHOOL AND NEIGHBORHOOD EFFECTS Joseph G. Altonji Richard K. Mansfield Working Paper 20781 http://www.nber.org/papers/w20781 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 December 2014 We thank Steven Berry, Greg Duncan, Phil Haile, Hidehiko Ichimura, Amanda Kowalski, Costas Meghir, Richard Murnane, Douglas Staiger, Jonathan Skinner, Shintaro Yamiguchi and as well as seminar participants at Cornell University, Dartmouth College, Duke University, the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, McMaster University, the NBER Economics of Education Conference, Yale University, Paris School of Economics, University of Colorado-Denver, and the University of Western Ontario for helpful comments and discussions. This research uses data from the National Center for Education Statistics as well as from North Carolina Education Research Data Center at Duke University. We acknowledge both the U.S. Department of Education and the North Carolina Department of Public Instruction for collecting and providing this information. We would also thank the Russell Sage Foundation and the Yale Economics Growth Center for financial support. A portion of this research was conducted while Altonji was a visitor at the LEAP Center and the Department of Economics, Harvard University The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer- reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. -

Economics 250A Course Outline and Reading List

Economics 250a Course Outline and Reading List This is the first course in the graduate labor economics sequence, and will focus on labor supply, labor demand, and simple search models. The emphasis of the course is on linking basic theoretical insights with empirical patterns in the labor market, using a combination of methodologies. Students are expected to have completed first year micro, marco, and econometrics courses. There will be a number of problem sets throughout the term, which all students must hand in (though working in groups is strongly encouraged). Students are expected to have familiarity with programs like Stata and Matlab. I will be adjusting the content of the course and adding some additional readings. I will also hand out my lecture notes. I recommend reading the starred paper(s) in each section before the lecture, and as many of the other papers as possible. Lecture 1: Review of basic consumer theory; functional form, aggregation, discrete choice Mas-Colell, Whintoe and Green, chapters 3 and 4. Angus Deaton and John Muellbauer, Economics and Consumer Behavior, Cambridge Press, 1980 Geoffrey Jehle and Philip Reny, Advanced Microeconomic Theory (2nd ed), Addision Wes- ley, 2001 John Chipman, "Aggregation and Estimation in the Theory of Demand" History of Po- litical Economy 38 (annual supplement), pp. 106-125. Kenneth Train. Discrete Choice Methods with Simulation, Cambridge Press 2003. Kenneth A. Small and Harvey A. Rosen "Applied Welfare Economics with Discrete Choice Models." Econometrica, 49 (January 1981), pp. 105-130. Lectures 2-4: Static Labor Supply **You should review the Handbook of Labor Economics chapters by Pencavel (volume 1) and Blundell and MaCurdy (volume 3a).