Alain Platel Times Bold, 18Pt

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BIO Stéphane Galland

Stéphane Galland was born into a musical family and received his first drum set at the age of three. He decided to take lessons in classical percussion when he reached the age of nine, at the conservatory at Huy (Belgium) and started playing jazz with his fellow pianist Eric Legnini two years later. At the age of 13, having had the opportunity to play with the best jazz musicians in Belgium, he developed a growing interest in this musical field. Always in search of new musical experiences, he met Pierre Vandormael, Fabrizio Cassol and Michel Hatzigeorgiou, and later with the last two, formed the band called AKA MOON. The band, which recorded over 20 CDs and performed worldwide (Europe, Africa, Asia, the United States, Canada, South America, the Caribbean Islands, India…), has been a unique and invaluable field of development and experimentation with different musical traditions. This led Stéphane Galland to record and perform with the Malian star Oumou Sangare, Senegalese master Doudou N'diaye Rose (Miles Davis, Rolling Stones, Peter Gabriel...), the Great and undisputed South Indian master of Mridangam Umayalpuram K. Sivaraman, the Turkish master of percussion Misirli Ahmet, and many different artists from Africa, India, Asia, Europe and America. Other than that, Stéphane Galland has been playing and recording with numerous famous artists from different horizons including Joe Zawinul, Joe Lovano, Toots Thielemans, Philip Catherine, Mark Turner, Robin Eubanks and singers Ozark Henry, David Linx, Axelle Red, Zap Mama, Novastar as well as many different groups using new developments in rhythm and harmony such as Dhafer Youssef, Nguyên Lê, Nelson Veras, Thôt, Kartet. -

Repor 1 Resumes

REPOR 1RESUMES ED 018 277 PS 000 871 TEACHING GENERAL MUSIC, A RESOURCE HANDBOOK FOR GRADES 7 AND 8. BY- SAETVEIT, JOSEPH G. AND OTHERS NEW YORK STATE EDUCATION DEPT., ALBANY PUB DATE 66 EDRS PRICEMF$0.75 HC -$7.52 186P. DESCRIPTORS *MUSIC EDUCATION, *PROGRAM CONTENT, *COURSE ORGANIZATION, UNIT PLAN, *GRADE 7, *GRADE 8, INSTRUCTIONAL MATERIALS; BIBLIOGRAPHIES, MUSIC TECHNIQUES, NEW YORK, THIS HANDBOOK PRESENTS SPECIFIC SUGGESTIONS CONCERNING CONTENT, METHODS, AND MATERIALS APPROPRIATE FOR USE IN THE IMPLEMENTATION OF AN INSTRUCTIONAL PROGRAM IN GENERAL MUSIC FOR GRADES 7 AND 8. TWENTY -FIVE TEACHING UNITS ARE PROVIDED AND ARE RECOMMENDED FOR ADAPTATION TO MEET SITUATIONAL CONDITIONS. THE TEACHING UNITS ARE GROUPED UNDER THE GENERAL TOPIC HEADINGS OF(1) ELEMENTS OF MUSIC,(2) THE SCIENCE OF SOUND,(3) MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS,(4) AMERICAN FOLK MUSIC, (5) MUSIC IN NEW YORK STATE,(6) MUSIC OF THE THEATER,(7) MUSIC FOR INSTRUMENTAL GROUPS,(8) OPERA,(9) MUSIC OF OTHER CULTURES, AND (10) HISTORICAL PERIODS IN MUSIC. THE PRESENTATION OF EACH UNIT CONSISTS OF SUGGESTIONS FOR (1) SETTING THE STAGE' (2) INTRODUCTORY DISCUSSION,(3) INITIAL MUSICAL EXPERIENCES,(4) DISCUSSION AND DEMONSTRATION, (5) APPLICATION OF SKILLS AND UNDERSTANDINGS,(6) RELATED PUPIL ACTIVITIES, AND(7) CULMINATING CLASS ACTIVITY (WHERE APPROPRIATE). SUITABLE PERFORMANCE LITERATURE, RECORDINGS, AND FILMS ARE CITED FOR USE WITH EACH OF THE UNITS. SEVEN EXTENSIVE BE.LIOGRAPHIES ARE INCLUDED' AND SOURCES OF BIBLIOGRAPHICAL ENTRIES, RECORDINGS, AND FILMS ARE LISTED. (JS) ,; \\',,N.k-*:V:.`.$',,N,':;:''-,",.;,1,4 / , .; s" r . ....,,'IA, '','''N,-'0%')',", ' '4' ,,?.',At.: \.,:,, - ',,,' :.'v.'',A''''',:'- :*,''''.:':1;,- s - 0,- - 41tl,-''''s"-,-N 'Ai -OeC...1%.3k.±..... -,'rik,,I.k4,-.&,- ,',V,,kW...4- ,ILt'," s','.:- ,..' 0,4'',A;:`,..,""k --'' .',''.- '' ''-. -

I Silenti the Next Creation of Fabrizio Cassol and Tcha Limberger Directed by Lisaboa Houbrechts

I SILENTI THE NEXT CREATION OF FABRIZIO CASSOL AND TCHA LIMBERGER DIRECTED BY LISABOA HOUBRECHTS Notre Dame de la détérioration © The Estate of Erwin Blumenfeld, photo Erwin Blumenfeld vers 1930 THE GOAL For several years Fabrizio Cassol has been concentrating on this form, said to be innovative, between concert, opera, dance and theatre. It brings together several artistic necessities and commitments, with the starting point of previously composed music that follows its own narrative. His recent projects, such as Coup Fatal and Requiem pour L. with Alain Platel and Macbeth with Brett Bailey, are examples of this. “I Silenti proposes to be the poetical expression of those who are reduced to silence, the voiceless, those who grow old or have disappeared with time, the blank pages of non-written letters, blindness, emptiness and ruins that could be catalysers to other ends: those of comfort, recovery, regeneration and beauty.” THE MUSIC Monteverdi’s Madrigals, the first vocal music of our written tradition to express human emotions with its dramas, passions and joys. These Madrigals, composed between 1587 and 1638, are mainly grouped around three themes: love, separation and war. The music is rooted, for the first time, in the words and their meaning, using poems by Pétraque, Le Tasse or Marino. It is during the evolution of this form and the actual heart of these polyphonies that Monteverdi participated in the creation of the Opera as a new genre. Little by little the voices become individualized giving birth to “arias and recitatives”, like suspended songs prolonging the narrative of languorous grievances. -

Starten Met Jazz

Themalijst Starten met Jazz Inleiding De Openbare Bibliotheek Kortrijk heeft een zeer uitgebreide jazzcollectie een paar duizend cd’s en een paar duizend vinylelpees) waardoor het voor een leek moeilijk is het bos door de bomen te zien. Ik zie voor de leek die iets meer wil weten ver jazzmuziek drie opties: 1. Je komt naar de Bib en grasduint wat in onze fantastische collectie. Grote kans dat je de ‘verkeerde’ cd’s meeneemt en voorgoed de jazz afzweert. Wat jammer zou zijn.. 2. Je neemt enkel verzamel-cd’s mee, bijvoorbeeld de Klara cd’s 3. Ok, dan heb je een staalkaart van het beste wat er ooit verschenen is en wil je misschien nog iets dieper gaan, meer exploreren, meer voelen wat échte jazz is.. Dan lees je 4. De beknopte lijst hieronder die chronologisch in enkele tientallen cd’s je wegwijs maakt in de verschillende subgenres van de jazz. Verwacht geen uitgebreide biografieën of discografieën maar een kort situeren van de belangrijkste stromingen met haar prominentste vertegenwoordigers. Dit is alleen maar een kennismaking, een aanzet. Maar dit document probeert een chronologisch overzicht te geven met de belangrijkste namen per sub genre. Als je van al deze artiesten één cd beluisterd hebt, kan je al wat meepraten voor jazz. Het is belangrijk op te merken dat al die sub genres soms zeer lang blijven en zelfs heropleven. Uiteraard overlappen ze elkaar in de tijd. En weinig muzikanten beperken zich echt tot één stijl. Jazzrecensent Mark Van den Hoof stelt dat na de jaren ‘60 niets nieuws meer gebeurde in de jazz en dat men zich beperkt tot het spelen in de stijlen van de vorige eeuw. -

Cool Trombone Lover

NOVEMBER 2013 - ISSUE 139 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM ROSWELL RUDD COOL TROMBONE LOVER MICHEL • DAVE • GEORGE • RELATIVE • EVENT CAMILO KING FREEMAN PITCH CALENDAR “BEST JAZZ CLUBS OF THE YEAR 2012” SMOKE JAZZ & SUPPER CLUB • HARLEM, NEW YORK CITY FEATURED ARTISTS / 7:00, 9:00 & 10:30pm ONE NIGHT ONLY / 7:00, 9:00 & 10:30pm RESIDENCIES / 7:00, 9:00 & 10:30pm Fri & Sat, Nov 1 & 2 Wed, Nov 6 Sundays, Nov 3 & 17 GARY BARTZ QUARTET PLUS MICHAEL RODRIGUEZ QUINTET Michael Rodriguez (tp) ● Chris Cheek (ts) SaRon Crenshaw Band SPECIAL GUEST VINCENT HERRING Jeb Patton (p) ● Kiyoshi Kitagawa (b) Sundays, Nov 10 & 24 Gary Bartz (as) ● Vincent Herring (as) Obed Calvaire (d) Vivian Sessoms Sullivan Fortner (p) ● James King (b) ● Greg Bandy (d) Wed, Nov 13 Mondays, Nov 4 & 18 Fri & Sat, Nov 8 & 9 JACK WALRATH QUINTET Jason Marshall Big Band BILL STEWART QUARTET Jack Walrath (tp) ● Alex Foster (ts) Mondays, Nov 11 & 25 Chris Cheek (ts) ● Kevin Hays (p) George Burton (p) ● tba (b) ● Donald Edwards (d) Captain Black Big Band Doug Weiss (b) ● Bill Stewart (d) Wed, Nov 20 Tuesdays, Nov 5, 12, 19, & 26 Fri & Sat, Nov 15 & 16 BOB SANDS QUARTET Mike LeDonne’s Groover Quartet “OUT AND ABOUT” CD RELEASE LOUIS HAYES Bob Sands (ts) ● Joel Weiskopf (p) Thursdays, Nov 7, 14, 21 & 28 & THE JAZZ COMMUNICATORS Gregg August (b) ● Donald Edwards (d) Gregory Generet Abraham Burton (ts) ● Steve Nelson (vibes) Kris Bowers (p) ● Dezron Douglas (b) ● Louis Hayes (d) Wed, Nov 27 RAY MARCHICA QUARTET LATE NIGHT RESIDENCIES / 11:30 - Fri & Sat, Nov 22 & 23 FEATURING RODNEY JONES Mon The Smoke Jam Session Chase Baird (ts) ● Rodney Jones (guitar) CYRUS CHESTNUT TRIO Tue Cyrus Chestnut (p) ● Curtis Lundy (b) ● Victor Lewis (d) Mike LeDonne (organ) ● Ray Marchica (d) Milton Suggs Quartet Wed Brianna Thomas Quartet Fri & Sat, Nov 29 & 30 STEVE DAVIS SEXTET JAZZ BRUNCH / 11:30am, 1:00 & 2:30pm Thu Nickel and Dime OPS “THE MUSIC OF J.J. -

Marie Collier: a Life

Marie Collier: a life Kim Kemmis A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History The University of Sydney 2018 Figure 1. Publicity photo: the housewife diva, 3 July 1965 (Alamy) i Abstract The Australian soprano Marie Collier (1927-1971) is generally remembered for two things: for her performance of the title role in Puccini’s Tosca, especially when she replaced the controversial singer Maria Callas at late notice in 1965; and her tragic death in a fall from a window at the age of forty-four. The focus on Tosca, and the mythology that has grown around the manner of her death, have obscured Collier’s considerable achievements. She sang traditional repertoire with great success in the major opera houses of Europe, North and South America and Australia, and became celebrated for her pioneering performances of twentieth-century works now regularly performed alongside the traditional canon. Collier’s experiences reveal much about post-World War II Australian identity and cultural values, about the ways in which the making of opera changed throughout the world in the 1950s and 1960s, and how women negotiated their changing status and prospects through that period. She exercised her profession in an era when the opera industry became globalised, creating and controlling an image of herself as the ‘housewife-diva’, maintaining her identity as an Australian artist on the international scene, and developing a successful career at the highest level of her artform while creating a fulfilling home life. This study considers the circumstances and mythology of Marie Collier’s death, but more importantly shows her as a woman of the mid-twentieth century navigating the professional and personal spheres to achieve her vision of a life that included art, work and family. -

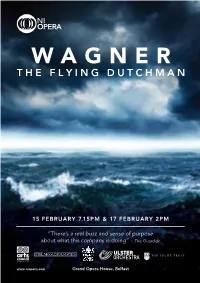

There's a Real Buzz and Sense of Purpose About What This Company Is Doing

15 FEBRUARY 7.15PM & 17 FEBRUARY 2PM “There’s a real buzz and sense of purpose about what this company is doing” ~ The Guardian www.niopera.com Grand Opera House, Belfast Welcome to The Grand Opera House for this new production of The Flying Dutchman. This is, by some way, NI Opera’s biggest production to date. Our very first opera (Menotti’s The Medium, coincidentally staged two years ago this month) utilised just five singers and a chamber band, and to go from this to a grand opera demanding 50 singers and a full symphony orchestra in such a short space of time indicates impressive progress. Similarly, our performances of Noye’s Fludde at the Beijing Music Festival in October, and our recent Irish Times Theatre Award nominations for The Turn of the Screw, demonstrate that our focus on bringing high quality, innovative opera to the widest possible audience continues to bear fruit. It feels appropriate for us to be staging our first Wagner opera in the bicentenary of the composer’s birth, but this production marks more than just a historical anniversary. Unsurprisingly, given the cost and complexities involved in performing Wagner, this will be the first fully staged Dutchman to be seen in Northern Ireland for generations. More unexpectedly, perhaps, this is the first ever new production of a Wagner opera by a Northern Irish company. Northern Ireland features heavily in this production. The opera begins and ends with ships and the sea, and it does not take too much imagination to link this back to Belfast’s industrial heritage and the recent Titanic commemorations. -

June 1911) James Francis Cooke

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 John R. Dover Memorial Library 6-1-1911 Volume 29, Number 06 (June 1911) James Francis Cooke Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude Part of the Composition Commons, Ethnomusicology Commons, Fine Arts Commons, History Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, Music Education Commons, Musicology Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, Music Performance Commons, Music Practice Commons, and the Music Theory Commons Recommended Citation Cooke, James Francis. "Volume 29, Number 06 (June 1911)." , (1911). https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude/570 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the John R. Dover Memorial Library at Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 361 THE ETUDE -4 m UP-TO-DATE PREMIUMS _OF STANDARD QUALITY__ K MONTHLY JOURNAL FOR THE MUSICIAN, THE MUSIC STUDENT, AND ALL MUSIC LOVERS. Edited by JAMES FRANCIS COOKE », Alaska, Cuba, Porto Kieo, 50 WEBSTER’S NEW STANDARD 4 DICTIONARY Illustrated. NEW U. S. CENSUS In Combination with THE ETUDE money orders, bank check letter. United States postage ips^are always received for cash. Money sent gerous, and iponsible for its safe T&ke Your THE LAST WORD IN DICTIONARIES Contains DISCONTINUANCE isli the journal Choice o! the THE NEW WORDS Explicit directions Books: as well as ime of expiration, RENEWAL.—No is sent for renewals. The $2.50 Simplified Spelling, „„ ...c next issue sent you will lie printed tile date on wliicli your Webster’s Synonyms and Antonyms, subscription is paid up, which serves as a New Standard receipt for your subscription. -

Labelnight Programmafolder Def.Indd

FEEST VAN DE BELGISCHE JAZZ ZATERDAG 8 OKTOBER 2016 In februari 2012 sloegen het Concertgebouw en De Werf de handen in elkaar voor een eerste W.E.R.F.- Labelnight. Deze eerste editie huldigde niet alleen 100 releases op het Brugse label, maar vierde even- eens het tienjarige jubileum van het Concertgebouw. De formule bleek een schot in de roos en een ver- volg kon dan ook niet uitblijven! Vandaag draait het W.E.R.F.-label nog steeds op volle toeren en stevent het af op 150 titels. Wat oorspronkelijk startte in 1993 als een eenmalige ondersteuning aan de Brugse pianist Kris Defoort, groeide uit tot wellicht het belangrijkste jazzlabel in Vlaanderen. De oneindige lijst aan jazzmuzikanten die reeds voor het label opnamen, leest als een encyclopedie van de Belgische 18:00 KRIS DEFOORT’S DIVING POET SOCIETY CONCERTZAAL jazzgeschiedenis van de afgelopen 25 jaar. Doorheen de jaren groeiden dan ook heel wat artiesten met JAZZCONCERTEN IN DE WERF NAJAAR 2016 ROBIN VERHEYEN QUARTET het label uit tot gevestigde waarden in het circuit. Voor deze tweede Labelnight selecteerden we zowel jonge leeuwen als vertrouwde gezichten. Op het programma staat onder meer Kris Defoorts nieuwe cre- 19:00 SCHNTZL KAMERMUZIEKZAAL atie Diving Poet Society met special guest Veronika Harcsa, het jonge duo SCHNTZL, Chris Joris Home VR. 21 OKT. ANTOINE PIERRE URBEX The Bach Riddles - Wereldpremière Project, Sander De Winne – Bram De Looze Duo , Bart Defoort Quintet, Jean-Paul Estiévenart – Steven Woensdag 18.01.2017 Delannoye Quartet, enzovoort. Een mix van generaties en stijlen. ZO. 30 OKT. OMER AVITAL QUINTET (* locatie Vrijstaat O in Oostende) BART DEFOORT QUINTET STUDIO 1 20:00 Kamermuziekzaal VR. -

Munt 6, 1000 Brussel. Niet Op De Openbare Weg Gooien

© Hugo Lefèvre & Francis Vanhee • Verantwoordelijke uitgever: Roel Leemans - Munt 6, 1000 Brussel. Niet op de openbare weg gooien. JORIS PRECKLER Klara Pierre Van Dormael Octurn / North Country Suite (2007) Octurn, ondertussen een hecht ensemble, opereert als expe- rimenteel platform, met pianist Jozef Dumoulin en saxofo- Muntpunt vroeg een aantal jazzkenners, Eric Legnini Trio nist Bo Van der Werf als drijvende krachten. De voortreffe- Natural Balance (1991) lijke bandleden gaan op het podium tot het uiterste, maar binnens- en buitenshuis, naar hun Een trioplaat van pianist Eric Legnini met de toen nog jonge drummer Stéphane altijd in functie van het collectieve resultaat. Hun reactie- Galland. Dit juweeltje haalt makkelijk het niveau van kleppers als Brad Mehldau vermogen is vlijmscherp, en de muziek is van een constant, favoriete Belgische jazzplaten van de of zelfs Bill Evans. torenhoog niveau. Inzet en enthousiasme brengt hen samen en laat hen ook individueel schitteren. De lievelingsplaat laatste jaren. Wij spoorden al die albums EN - A trio record by pianist Eric Legnini with the then still young drummer Stéphane blijft ‘North country suite’: complexe muziek met een hoek Galland. This musical gem easily reaches the level of the biggest names in jazz, such as Brad af, onvoorspelbaar ook, ijzersterke jazz die verschillende stij- op en maakten ze beschikbaar om te Mehldau or even Bill Evans. len en invloeden samenbrengt. Pierre Van Dormael slaagt erin FR - Un disque en trio du pianiste Eric Legnini avec le batteur Stéphane Galland, qui était om de grenzen tussen jazz, elektronica, niet-westerse klassiek lenen. Klaar om jezelf in de opwindende encore tout jeune. -

Belgianjazzdirectory2011.Pdf

Preface Introduction Jazz in Belgium 2011, Courage in the delta The Artists Unity is strength! Hamster Axis of the one-click Panther Manuel Hermia Trio After three editions of the Flemish Jazz Meeting we are very pleased De Beren Gieren to present you with a new initiative that aims to unite the jazz scenes Collapse of both parts of the country in one common objective: to firmly put Pascal Mohy Trio Belgian jazz on the map of Flanders, Wallonia, Brussels and Europe, Rêve d’éléphant Orchestra thus promoting mutual knowledge. Tuur Florizoone - Mixtuur Nicolas Kummert Voices The Belgian Jazz Meeting is a mini showcase festival that gives national Rackham and international promoters and the press the chance to see 12 bands Christian Mendoza Group at work. Joachim Badenhorst At the same time, the meeting is an ideal forum for colleagues to meet Giovanni Barcella – Jeroen Van Herzeele Duo each other, stay connected, expand networks and exchange ideas. Belgian Jazz Directory For the selection, we asked a jury of about 60 members from all corners Organisations of the country to select 12 artists with international potential who could Jazz Festivals benefit from our support. The result is not a hit parade but rather a very Venues diverse palette of hungry young things as well as more established Jazz Clubs/Small Music Venues names that never tire of reinventing themselves. This CD introduces Media each one of them with a recent composition. Information Platforms Management/Booking Agencies The second part of this booklet contains an overview of the most Labels & Distribution important organisations, concert venues, festivals, etc… for jazz in Belgium. -

June 1924) James Francis Cooke

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 John R. Dover Memorial Library 6-1-1924 Volume 42, Number 06 (June 1924) James Francis Cooke Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude Part of the Composition Commons, Ethnomusicology Commons, Fine Arts Commons, History Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, Music Education Commons, Musicology Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, Music Performance Commons, Music Practice Commons, and the Music Theory Commons Recommended Citation Cooke, James Francis. "Volume 42, Number 06 (June 1924)." , (1924). https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude/713 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the John R. Dover Memorial Library at Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MVSIC “ETVDE MAGA ZINE Price 25 cents JUNE, 1924 $2.00 a Year JUNE 1924 Page 363 THE ETUDE New Publications that will serve Many Schools and Colleges Noteworthy Announcements in this Issue on Pages 363, 384, 366, 367, 368 _ Branches of the Music Profession \AMERICAN INSTITUTE ^njumitr g>rluml of JHuBiral Ir-Buralton Professional The Presser Policy is to Issue Only Those Book Publications that have Merit and are of Real Value \0F APPLIED MUSIC Music taught thru the awakening of the inner consciousness Directory to the Profession. With Compilations and Teaching Works the Aim is to Make Each Work One of \ Metropolitan College of Music High Standing in its Particular Classification.