Wealth, Lobbying and Distributive Justice in the Wake of the Economic Crisis C.M.A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Value, Caution and Accountability in an Era of Large Banks and Complex Finance*

2011-2012 BETTING BIG 765 BETTING BIG: VALUE, CAUTION AND ACCOUNTABILITY IN AN ERA OF LARGE BANKS AND COMPLEX FINANCE* LAWRENCE G. BAXTER** Abstract Big banks are controversial. Their supporters maintain that they offer products, services and infrastructure that smaller banks simply cannot match and enjoy unprecedented economies of scale and scope. Detractors worry about the risks generated by big banks, their threats to financial stability, and the way they externalize costs of operation to the public. This article explains why there is no conclusive argument one way or the other and why simple measures for restricting the danger of big banks are neither plausible nor effective. The complex ecology of modern finance and the management and regulatory challenges generated by ultra-large banking, however, cast serious doubt on the proposition that the benefits of big banking outweigh its risks. Consequently, two general principles are proposed for further consideration. First, big banks should bear a greater degree of public accountability by reforming certain principles of corporate governance to require greater representation of public interests at the board and executive levels of big banks. Second, given the unproven promises of performance by big banks, their unimpressive actual record of performance, and the many hazards they inevitably generate or encounter, financial regulators should consciously adopt a strict cautionary approach. Under this approach, big banks would bear a very heavy onus to demonstrate in concrete terms that their continued growth – and even the maintenance of their current scale – can be adequately managed and supervised. * © Lawrence G. Baxter. ** Professor of the Practice of Law, Duke Law School. -

Notes and Sources for Evil Geniuses: the Unmaking of America: a Recent History

Notes and Sources for Evil Geniuses: The Unmaking of America: A Recent History Introduction xiv “If infectious greed is the virus” Kurt Andersen, “City of Schemes,” The New York Times, Oct. 6, 2002. xvi “run of pedal-to-the-medal hypercapitalism” Kurt Andersen, “American Roulette,” New York, December 22, 2006. xx “People of the same trade” Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations, ed. Andrew Skinner, 1776 (London: Penguin, 1999) Book I, Chapter X. Chapter 1 4 “The discovery of America offered” Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy In America, trans. Arthur Goldhammer (New York: Library of America, 2012), Book One, Introductory Chapter. 4 “A new science of politics” Tocqueville, Democracy In America, Book One, Introductory Chapter. 4 “The inhabitants of the United States” Tocqueville, Democracy In America, Book One, Chapter XVIII. 5 “there was virtually no economic growth” Robert J Gordon. “Is US economic growth over? Faltering innovation confronts the six headwinds.” Policy Insight No. 63. Centre for Economic Policy Research, September, 2012. --Thomas Piketty, “World Growth from the Antiquity (growth rate per period),” Quandl. 6 each citizen’s share of the economy Richard H. Steckel, “A History of the Standard of Living in the United States,” in EH.net (Economic History Association, 2020). --Andrew McAfee and Erik Brynjolfsson, The Second Machine Age: Work, Progress, and Prosperity in a Time of Brilliant Technologies (New York: W.W. Norton, 2016), p. 98. 6 “Constant revolutionizing of production” Friedrich Engels and Karl Marx, Manifesto of the Communist Party (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1969), Chapter I. 7 from the early 1840s to 1860 Tomas Nonnenmacher, “History of the U.S. -

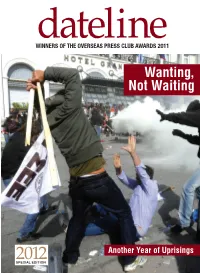

Wanting, Not Waiting

WINNERSdateline OF THE OVERSEAS PRESS CLUB AWARDS 2011 Wanting, Not Waiting 2012 Another Year of Uprisings SPECIAL EDITION dateline 2012 1 letter from the president ne year ago, at our last OPC Awards gala, paying tribute to two of our most courageous fallen heroes, I hardly imagined that I would be standing in the same position again with the identical burden. While last year, we faced the sad task of recognizing the lives and careers of two Oincomparable photographers, Tim Hetherington and Chris Hondros, this year our attention turns to two writers — The New York Times’ Anthony Shadid and Marie Colvin of The Sunday Times of London. While our focus then was on the horrors of Gadhafi’s Libya, it is now the Syria of Bashar al- Assad. All four of these giants of our profession gave their lives in the service of an ideal and a mission that we consider so vital to our way of life — a full, complete and objective understanding of a world that is so all too often contemptuous or ignorant of these values. Theirs are the same talents and accomplishments to which we pay tribute in each of our awards tonight — and that the Overseas Press Club represents every day throughout the year. For our mission, like theirs, does not stop as we file from this room. The OPC has moved resolutely into the digital age but our winners and their skills remain grounded in the most fundamental tenets expressed through words and pictures — unwavering objectivity, unceasing curiosity, vivid story- telling, thought-provoking commentary. -

The Donald Trump-Rupert Murdoch Relationship in the United States

The Donald Trump-Rupert Murdoch relationship in the United States When Donald Trump ran as a candidate for the Republican presidential nomination, Rupert Murdoch was reported to be initially opposed to him, so the Wall Street Journal and the New York Post were too.1 However, Roger Ailes and Murdoch fell out because Ailes wanted to give more positive coverage to Trump on Fox News.2 Soon afterwards, however, Fox News turned more negative towards Trump.3 As Trump emerged as the inevitable winner of the race for the nomination, Murdoch’s attitude towards Trump appeared to shift, as did his US news outlets.4 Once Trump became the nominee, he and Rupert Murdoch effectively concluded an alliance of mutual benefit: Murdoch’s news outlets would help get Trump elected, and then Trump would use his powers as president in ways that supported Rupert Murdoch’s interests. An early signal of this coming together was Trump’s public attacks on the AT&T-Time Warner merger, 21st Century Fox having tried but failed to acquire Time Warner previously in 2014. Over the last year and a half, Fox News has been the major TV news supporter of Donald Trump. Its coverage has displayed extreme bias in his favour, offering fawning coverage of his actions and downplaying or rubbishing news stories damaging to him, while also leading attacks against Donald Trump’s opponent in the 2016 presidential election, Hillary Clinton. Ofcom itself ruled that several Sean Hannity programmes in August 2016 were so biased in favour of Donald Trump and against Hillary Clinton that they breached UK impartiality rules.5 During this period, Rupert Murdoch has been CEO of Fox News, in which position he is also 1 See e.g. -

How America Lost Its Mind the Nation’S Current Post-Truth Moment Is the Ultimate Expression of Mind-Sets That Have Made America Exceptional Throughout Its History

1 How America Lost Its Mind The nation’s current post-truth moment is the ultimate expression of mind-sets that have made America exceptional throughout its history. KURT ANDERSEN SEPTEMBER 2017 ISSUE THE ATLANTIC “You are entitled to your own opinion, but you are not entitled to your own facts.” — Daniel Patrick Moynihan “We risk being the first people in history to have been able to make their illusions so vivid, so persuasive, so ‘realistic’ that they can live in them.” — Daniel J. Boorstin, The Image: A Guide to Pseudo-Events in America (1961) 1) WHEN DID AMERICA become untethered from reality? I first noticed our national lurch toward fantasy in 2004, after President George W. Bush’s political mastermind, Karl Rove, came up with the remarkable phrase reality-based community. People in “the reality-based community,” he told a reporter, “believe that solutions emerge from your judicious study of discernible reality … That’s not the way the world really works anymore.” A year later, The Colbert Report went on the air. In the first few minutes of the first episode, Stephen Colbert, playing his right-wing-populist commentator character, performed a feature called “The Word.” His first selection: truthiness. “Now, I’m sure some of the ‘word police,’ the ‘wordinistas’ over at Webster’s, are gonna say, ‘Hey, that’s not a word!’ Well, anybody who knows me knows that I’m no fan of dictionaries or reference books. They’re elitist. Constantly telling us what is or isn’t true. Or what did or didn’t happen. -

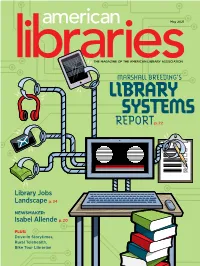

Download on the AASL Website an Anonymous Funder Donated $170,000 Tee, and the Rainbow Round Table at Bit.Ly/AASL-Statements

May 2021 THE MAGAZINE OF THE AMERICAN LIBRARY ASSOCIATION MARSHALL BREEDING’S LIBRARY SYSTEMS REPORTp. 22 Library Jobs Landscape p. 34 NEWSMAKER: Isabel Allende p. 20 PLUS: Drive-In Storytimes, Rural Telehealth, Bike Tour Librarian This Summer! Join us online at the event created and curated for the library community. Event Highlights • Educational programming • COVID-19 information for libraries • News You Can Use sessions highlighting • Interactive Discussion Groups new research and advances in libraries • Presidents' Programs • Memorable and inspiring featured authors • Livestreamed and on-demand sessions and celebrity speakers • Networking opportunities to share and The Library Marketplace with more than • connect with peers 250 exhibitors, Presentation Stages, Swag-A-Palooza, and more • Event content access for a full year ALA Members who have been recently furloughed, REGISTER TODAY laid o, or are experiencing a reduction of paid alaannual.org work hours are invited to register at no cost. #alaac21 Thank you to our Sponsors May 2021 American Libraries | Volume 52 #5 | ISSN 0002-9769 COVER STORY 2021 LIBRARY SYSTEMS REPORT Advancing library technologies in challenging times | p. 22 BY Marshall Breeding FEATURES 38 JOBS REPORT 34 The Library Employment Landscape Job seekers navigate uncertain terrain BY Anne Ford 38 The Virtual Job Hunt Here’s how to stand out, both as an applicant and an employer BY Claire Zulkey 42 Serving the Community at All Times Cultural inclusivity programming during a pandemic BY Nicanor Diaz, Virginia Vassar -

Print Hardcover Best Sellers

Copyright © 2017 October 1, 2017 by The New York Times THE NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW Print Hardcover Best Sellers THIS LAST WEEKS THIS LAST WEEKS WEEK WEEK Fiction ON LIST WEEK WEEK Nonfiction ON LIST A COLUMN OF FIRE, by Ken Follett. (Viking) The lovers Ned 1 WHAT HAPPENED, by Hillary Rodham Clinton. (Simon & 1 1 1 Willard and Margery Fitzgerald find themselves on opposite sides Schuster) The first woman nominated for president by a major of a conflict between English Catholics and Protestants while political party details her campaign, mistakes she made, outside Queen Elizabeth fights to maintain her throne. forces that affected the outcome and how she recovered in its aftermath. THE GIRL WHO TAKES AN EYE FOR AN EYE, by David 1 2 Lagercrantz. (Knopf) Lisbeth Salander teams up with an UNBELIEVABLE, by Katy Tur. (Dey St.) The NBC News 1 2 investigative journalist to uncover the secrets of her childhood. A correspondent describes her work covering the 2016 campaign continuation of Stieg Larsson’s Millennium series. of the Republican nominee for president and his behavior toward her. 3 ENEMY OF THE STATE, by Kyle Mills. (Atria/Emily Bestler) Vince 2 3 Flynn’s character Mitch Rapp leaves the C.I.A. to go on a manhunt 1 ASTROPHYSICS FOR PEOPLE IN A HURRY, by Neil deGrasse 20 3 when the nephew of a Saudi King finances a terrorist group. Tyson. (Norton) A straightforward, easy-to-understand introduction to the universe. THE ROMANOV RANSOM, by Clive Cussler and Robin Burcell. 1 4 (Putnam) Sam and Remi Fargo search for two missing filmmakers 2 HILLBILLY ELEGY, by J. -

How America Went Haywire

Have Smartphones Why Women Bully Destroyed a Each Other at Work Generation? p. 58 BY OLGA KHAZAN Conspiracy Theories. Fake News. Magical Thinking. How America Went Haywire By Kurt Andersen The Rise of the Violent Left Jane Austen Is Everything The Whitest Music Ever John le Carré Goes SEPTEMBER 2017 Back Into the Cold THEATLANTIC.COM 0917_Cover [Print].indd 1 7/19/2017 1:57:09 PM TerTeTere msm appppply.ly Viistsits ameierier cancaanexpexpresre scs.cs.s com/om busbubusinesspsplatl inuummt to learnmn moreorer . Hogarth &Ogilvy Hogarth 212.237.7000 CODE: FILE: DESCRIPTION: 29A-008875-25C-PBC-17-238F.indd PBC-17-238F TAKE A BREAK BEFORE TAKING ONTHEWORLD ABREAKBEFORETAKING TAKE PUB/POST: The Atlantic -9/17issue(Due TheAtlantic SAP #: #: WORKORDER PRODUCTION: AP.AP PBC.17020.K.011 AP.AP al_stacked_l_18in_wide_cmyk.psd Art: D.Hanson AP17006A_003C_EarlyCheckIn_SWOP3.tif 008875 BLEED: TRIM: LIVE: (CMYK; 3881 ppi; Up toDate) (CMYK; 3881ppi;Up 15.25” x10” 15.75”x10.5” 16”x10.75” (CMYK; 908 ppi; Up toDate), (CMYK; 908ppi;Up 008875-13A-TAKE_A_BREAK_CMYK-TintRev.eps 008875-13A-TAKE_A_BREAK_CMYK-TintRev.eps (Up toDate), (Up AP- American Express-RegMark-4C.ai AP- AmericanExpress-RegMark-4C.ai (Up toDate), (Up sbs_fr_chg_plat_met- at americanexpress.com/exploreplatinum at PlatinumMembership Business of theworld Explore FineHotelsandResorts. hand-picked 975 atover head your andclear early Arrive TerTeTere msm appppply.ly Viistsits ameierier cancaanexpexpresre scs.cs.s com/om busbubusinesspsplatl inuummt to learnmn moreorer . Hogarth &Ogilvy Hogarth 212.237.7000 -

After the Meltdown

Tulsa Law Review Volume 45 Issue 3 Regulation and Recession: Causes, Effects, and Solutions for Financial Crises Spring 2010 After the Meltdown Daniel J. Morrissey Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.utulsa.edu/tlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Daniel J. Morrissey, After the Meltdown, 45 Tulsa L. Rev. 393 (2013). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.utulsa.edu/tlr/vol45/iss3/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by TU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Tulsa Law Review by an authorized editor of TU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Morrissey: After the Meltdown AFTER THE MELTDOWN Daniel J. Morrissey* We will not go back to the days of reckless behavior and unchecked excess that was at the heart of this crisis, where too many were motivated only by the appetite for quick kills and bloated bonuses. -President Barack Obamal The window of opportunityfor reform will not be open for long .... -Princeton Economist Hyun Song Shin 2 I. INTRODUCTION: THE MELTDOWN A. How it Happened One year after the financial markets collapsed, President Obama served notice on Wall Street that society would no longer tolerate the corrupt business practices that had almost destroyed the world's economy. 3 In "an era of rapacious capitalists and heedless self-indulgence," 4 an "ingenious elite" 5 set up a credit regime based on improvident * A.B., J.D., Georgetown University; Professor and Former Dean, Gonzaga University School of Law. This article is dedicated to Professor Tom Holland, a committed legal educator and a great friend to the author. -

Too Big to Fail — U.S. Banks' Regulatory Alchemy

Journal of Business & Technology Law Volume 14 | Issue 2 Article 2 Too Big to Fail — U.S. Banks’ Regulatory Alchemy: Converting an Obscure Agency Footnote into an “At Will” Nullification of Dodd-Frank’s Regulation of the Multi-Trillion Dollar Financial Swaps Market Michael Greenberger Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.umaryland.edu/jbtl Recommended Citation Michael Greenberger, Too Big to Fail — U.S. Banks’ Regulatory Alchemy: Converting an Obscure Agency Footnote into an “At Will” Nullification of Dodd-Frank’s Regulation of the Multi-Trillion Dollar Financial Swaps Market, 14 J. Bus. & Tech. L. 197 () Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.umaryland.edu/jbtl/vol14/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Academic Journals at DigitalCommons@UM Carey Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Business & Technology Law by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@UM Carey Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Too Big to Fail—U.S. Banks’ Regulatory Alchemy: Converting an Obscure Agency Footnote into an “At Will” Nullification of Dodd-Frank’s Regulation of the Multi-Trillion Dollar Financial Swaps Market MICHAEL GREENBERGER*©1 ΎLaw School Professor, University of Maryland Carey School of Law, and Founder and Director, University of Maryland Center for Health and Homeland Security (“CHHS”); former Director, Division of Trading and Markets, U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission. The Institute for New Economic Thinking (“INET”) funded and published this article as a working paper on the Social Sciences Research Network on June 19, 2018 at https://www.ineteconomics.org/uploads/papers/WP_74.pdf. -

Americans for Tax Fairness Selected Opinion Pieces on Corporate Inversions

AMERICANS FOR TAX FAIRNESS SELECTED OPINION PIECES ON CORPORATE INVERSIONS As of October 1, 2014 NATIONAL Fortune – Positively un-American Tax Dodgers, Allan Sloan, July 7, 2014 “Undermining the finances of the federal government by inverting helps undermine our economy. And that’s a bad thing, in the long run, for companies that do business in America.” Fortune – Foreign Tax Ploys Raise a Question: What is an American Company?, Allan Sloan, June 2, 2014 “But in the past few years, as the world has become more global and other countries have cut their corporate rates, a new exodus wave has started. ‘For the past 20 years, there’s been an arms race between the companies on the one hand and the IRS and Congress on the other, and the companies always seem to come up with better weapons,’ says tax expert Bob Willens.” The New York Times – Cracking Down on Corporate Tax Games, The Editorial Board, September 23, 2014 “New rules from the Treasury Department[2] are likely to slow the offensive practice that allows American companies to avoid taxes by merging with foreign rivals. Known as corporate inversions, these are complex, modern variations on the practices of yesteryear, when companies dodged their taxes by moving their addresses to post office boxes in the Caribbean.” The New York Times – At Walgreen, Renouncing Corporate Citizenship, Andrew Ross Sorkin, June 30, 2014 “In Walgreen’s case, an inversion would be an affront to United States taxpayers. The company, which also owns the Duane Reade chain in New York, reaps almost a quarter of -

Some Major Advertisers Step up the Pressure on Magazines to Alter Their Content, Will Editors Bend?

THE by Russ Baker SOME MAJOR ADVERTISERS STEP UP THE PRESSURE ON MAGAZINES TO ALTER THEIR CONTENT, WILL EDITORS BEND? In an effort to avoid potential conflicts, s there any doubt that advertisers reason to hope that other advertisers it is required that Chrysler Corporation mumble and sometimes roar about won’t ask for the same privilege. be alerted in advance of any and all edi- reporting that can hurt them? You will have thirty or forty adver- torial content that encompasses sexual, I That the auto giants don’t like tisers checking through the pages. political, social issues or any editorial pieces that, say point to auto safety They will send notes to publishers. that might be construed as provocative problems? Or that Big Tobacco hates I don’t see how any good citizen or offensive. Each and every issue that to see its glamorous, cheerful ads doesn’t rise to this occasion and say carries Chrysler advertising requires a juxtaposed with articles mentioning this development is un-American Written summary outlining major their best customers’ grim way of and a threat to freedom.” theme/articles appearing in upcoming death? When advertisers disapprove Hyperbole? Maybe not. Just about issues. These summaries are to be for- of an editorial climate, they can- any editor will tell you: the ad/edit Warded to PentaCorn prior to closing in and sometimes do take a hike. chemistry is changing for the worse. order to give Ch ysler ample time to re- But for Chrysler to push beyond Corporations and their ad agencies view and reschedule if desired.