Too Big to Fail — U.S. Banks' Regulatory Alchemy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Value, Caution and Accountability in an Era of Large Banks and Complex Finance*

2011-2012 BETTING BIG 765 BETTING BIG: VALUE, CAUTION AND ACCOUNTABILITY IN AN ERA OF LARGE BANKS AND COMPLEX FINANCE* LAWRENCE G. BAXTER** Abstract Big banks are controversial. Their supporters maintain that they offer products, services and infrastructure that smaller banks simply cannot match and enjoy unprecedented economies of scale and scope. Detractors worry about the risks generated by big banks, their threats to financial stability, and the way they externalize costs of operation to the public. This article explains why there is no conclusive argument one way or the other and why simple measures for restricting the danger of big banks are neither plausible nor effective. The complex ecology of modern finance and the management and regulatory challenges generated by ultra-large banking, however, cast serious doubt on the proposition that the benefits of big banking outweigh its risks. Consequently, two general principles are proposed for further consideration. First, big banks should bear a greater degree of public accountability by reforming certain principles of corporate governance to require greater representation of public interests at the board and executive levels of big banks. Second, given the unproven promises of performance by big banks, their unimpressive actual record of performance, and the many hazards they inevitably generate or encounter, financial regulators should consciously adopt a strict cautionary approach. Under this approach, big banks would bear a very heavy onus to demonstrate in concrete terms that their continued growth – and even the maintenance of their current scale – can be adequately managed and supervised. * © Lawrence G. Baxter. ** Professor of the Practice of Law, Duke Law School. -

Notes and Sources for Evil Geniuses: the Unmaking of America: a Recent History

Notes and Sources for Evil Geniuses: The Unmaking of America: A Recent History Introduction xiv “If infectious greed is the virus” Kurt Andersen, “City of Schemes,” The New York Times, Oct. 6, 2002. xvi “run of pedal-to-the-medal hypercapitalism” Kurt Andersen, “American Roulette,” New York, December 22, 2006. xx “People of the same trade” Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations, ed. Andrew Skinner, 1776 (London: Penguin, 1999) Book I, Chapter X. Chapter 1 4 “The discovery of America offered” Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy In America, trans. Arthur Goldhammer (New York: Library of America, 2012), Book One, Introductory Chapter. 4 “A new science of politics” Tocqueville, Democracy In America, Book One, Introductory Chapter. 4 “The inhabitants of the United States” Tocqueville, Democracy In America, Book One, Chapter XVIII. 5 “there was virtually no economic growth” Robert J Gordon. “Is US economic growth over? Faltering innovation confronts the six headwinds.” Policy Insight No. 63. Centre for Economic Policy Research, September, 2012. --Thomas Piketty, “World Growth from the Antiquity (growth rate per period),” Quandl. 6 each citizen’s share of the economy Richard H. Steckel, “A History of the Standard of Living in the United States,” in EH.net (Economic History Association, 2020). --Andrew McAfee and Erik Brynjolfsson, The Second Machine Age: Work, Progress, and Prosperity in a Time of Brilliant Technologies (New York: W.W. Norton, 2016), p. 98. 6 “Constant revolutionizing of production” Friedrich Engels and Karl Marx, Manifesto of the Communist Party (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1969), Chapter I. 7 from the early 1840s to 1860 Tomas Nonnenmacher, “History of the U.S. -

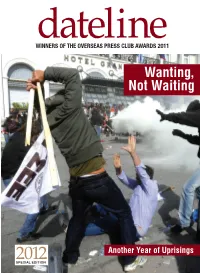

Wanting, Not Waiting

WINNERSdateline OF THE OVERSEAS PRESS CLUB AWARDS 2011 Wanting, Not Waiting 2012 Another Year of Uprisings SPECIAL EDITION dateline 2012 1 letter from the president ne year ago, at our last OPC Awards gala, paying tribute to two of our most courageous fallen heroes, I hardly imagined that I would be standing in the same position again with the identical burden. While last year, we faced the sad task of recognizing the lives and careers of two Oincomparable photographers, Tim Hetherington and Chris Hondros, this year our attention turns to two writers — The New York Times’ Anthony Shadid and Marie Colvin of The Sunday Times of London. While our focus then was on the horrors of Gadhafi’s Libya, it is now the Syria of Bashar al- Assad. All four of these giants of our profession gave their lives in the service of an ideal and a mission that we consider so vital to our way of life — a full, complete and objective understanding of a world that is so all too often contemptuous or ignorant of these values. Theirs are the same talents and accomplishments to which we pay tribute in each of our awards tonight — and that the Overseas Press Club represents every day throughout the year. For our mission, like theirs, does not stop as we file from this room. The OPC has moved resolutely into the digital age but our winners and their skills remain grounded in the most fundamental tenets expressed through words and pictures — unwavering objectivity, unceasing curiosity, vivid story- telling, thought-provoking commentary. -

Chapman Law Review

Chapman Law Review Volume 21 Board of Editors 2017–2018 Executive Board Editor-in-Chief LAUREN K. FITZPATRICK Managing Editor RYAN W. COOPER Senior Articles Editors Production Editor SUNEETA H. ISRANI MARISSA N. HAMILTON TAYLOR A. KENDZIERSKI CLARE M. WERNET Senior Notes & Comments Editor TAYLOR B. BROWN Senior Symposium Editor CINDY PARK Senior Submissions & Online Editor ALBERTO WILCHES –––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– Articles Editors ASHLEY C. ANDERSON KRISTEN N. KOVACICH ARLENE GALARZA STEVEN L. RIMMER NATALIE M. GAONA AMANDA M. SHAUGHNESSY-FORD ANAM A. JAVED DAMION M. YOUNG __________________________________________________________________ Staff Editors RAYMOND AUBELE AMY N. HUDACK JAMIE L. RICE CARLOS BACIO MEGAN A. LEE JAMIE L. TRAXLER HOPE C. BLAIN DANTE P. LOGIE BRANDON R. SALVATIERRA GEORGE E. BRIETIGAM DRAKE A. MIRSCH HANNAH B. STETSON KATHERINE A. BURGESS MARLENA MLYNARSKA SYDNEY L. WEST KYLEY S. CHELWICK NICHOLE N. MOVASSAGHI Faculty Advisor CELESTINE MCCONVILLE, Professor of Law CHAPMAN UNIVERSITY HAZEM H. CHEHABI ADMINISTRATION JEROME W. CWIERTNIA DALE E. FOWLER ’58 DANIELE C. STRUPPA BARRY GOLDFARB President STAN HARRELSON GAVIN S. HERBERT,JR. GLENN M. PFEIFFER WILLIAM K. HOOD Provost and Executive Vice ANDY HOROWITZ President for Academic Affairs MARK CHAPIN JOHNSON ’05 JENNIFER L. KELLER HAROLD W. HEWITT,JR. THOMAS E. MALLOY Executive Vice President and Chief SEBASTIAN PAUL MUSCO Operating Officer RICHARD MUTH (MBA ’05) JAMES J. PETERSON SHERYL A. BOURGEOIS HARRY S. RINKER Executive Vice President for JAMES B. ROSZAK University Advancement THE HONORABLE LORETTA SANCHEZ ’82 HELEN NORRIS MOHINDAR S. SANDHU Vice President and Chief RONALD M. SIMON Information Officer RONALD E. SODERLING KAREN R. WILKINSON ’69 THOMAS C. PIECHOTA DAVID W. -

ASD-Covert-Foreign-Money.Pdf

overt C Foreign Covert Money Financial loopholes exploited by AUGUST 2020 authoritarians to fund political interference in democracies AUTHORS: Josh Rudolph and Thomas Morley © 2020 The Alliance for Securing Democracy Please direct inquiries to The Alliance for Securing Democracy at The German Marshall Fund of the United States 1700 18th Street, NW Washington, DC 20009 T 1 202 683 2650 E [email protected] This publication can be downloaded for free at https://securingdemocracy.gmfus.org/covert-foreign-money/. The views expressed in GMF publications and commentary are the views of the authors alone. Cover and map design: Kenny Nguyen Formatting design: Rachael Worthington Alliance for Securing Democracy The Alliance for Securing Democracy (ASD), a bipartisan initiative housed at the German Marshall Fund of the United States, develops comprehensive strategies to deter, defend against, and raise the costs on authoritarian efforts to undermine and interfere in democratic institutions. ASD brings together experts on disinformation, malign finance, emerging technologies, elections integrity, economic coercion, and cybersecurity, as well as regional experts, to collaborate across traditional stovepipes and develop cross-cutting frame- works. Authors Josh Rudolph Fellow for Malign Finance Thomas Morley Research Assistant Contents Executive Summary �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 1 Introduction and Methodology �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� -

The Donald Trump-Rupert Murdoch Relationship in the United States

The Donald Trump-Rupert Murdoch relationship in the United States When Donald Trump ran as a candidate for the Republican presidential nomination, Rupert Murdoch was reported to be initially opposed to him, so the Wall Street Journal and the New York Post were too.1 However, Roger Ailes and Murdoch fell out because Ailes wanted to give more positive coverage to Trump on Fox News.2 Soon afterwards, however, Fox News turned more negative towards Trump.3 As Trump emerged as the inevitable winner of the race for the nomination, Murdoch’s attitude towards Trump appeared to shift, as did his US news outlets.4 Once Trump became the nominee, he and Rupert Murdoch effectively concluded an alliance of mutual benefit: Murdoch’s news outlets would help get Trump elected, and then Trump would use his powers as president in ways that supported Rupert Murdoch’s interests. An early signal of this coming together was Trump’s public attacks on the AT&T-Time Warner merger, 21st Century Fox having tried but failed to acquire Time Warner previously in 2014. Over the last year and a half, Fox News has been the major TV news supporter of Donald Trump. Its coverage has displayed extreme bias in his favour, offering fawning coverage of his actions and downplaying or rubbishing news stories damaging to him, while also leading attacks against Donald Trump’s opponent in the 2016 presidential election, Hillary Clinton. Ofcom itself ruled that several Sean Hannity programmes in August 2016 were so biased in favour of Donald Trump and against Hillary Clinton that they breached UK impartiality rules.5 During this period, Rupert Murdoch has been CEO of Fox News, in which position he is also 1 See e.g. -

True Conservative Or Enemy of the Base?

Paul Ryan: True Conservative or Enemy of the Base? An analysis of the Relationship between the Tea Party and the GOP Elmar Frederik van Holten (s0951269) Master Thesis: North American Studies Supervisor: Dr. E.F. van de Bilt Word Count: 53.529 September January 31, 2017. 1 You created this PDF from an application that is not licensed to print to novaPDF printer (http://www.novapdf.com) Page intentionally left blank 2 You created this PDF from an application that is not licensed to print to novaPDF printer (http://www.novapdf.com) Table of Content Table of Content ………………………………………………………………………... p. 3 List of Abbreviations……………………………………………………………………. p. 5 Chapter 1: Introduction…………………………………………………………..... p. 6 Chapter 2: The Rise of the Conservative Movement……………………….. p. 16 Introduction……………………………………………………………………… p. 16 Ayn Rand, William F. Buckley and Barry Goldwater: The Reinvention of Conservatism…………………………………………….... p. 17 Nixon and the Silent Majority………………………………………………….. p. 21 Reagan’s Conservative Coalition………………………………………………. p. 22 Post-Reagan Reaganism: The Presidency of George H.W. Bush……………. p. 25 Clinton and the Gingrich Revolutionaries…………………………………….. p. 28 Chapter 3: The Early Years of a Rising Star..................................................... p. 34 Introduction……………………………………………………………………… p. 34 A Moderate District Electing a True Conservative…………………………… p. 35 Ryan’s First Year in Congress…………………………………………………. p. 38 The Rise of Compassionate Conservatism…………………………………….. p. 41 Domestic Politics under a Foreign Policy Administration……………………. p. 45 The Conservative Dream of a Tax Code Overhaul…………………………… p. 46 Privatizing Entitlements: The Fight over Welfare Reform…………………... p. 52 Leaving Office…………………………………………………………………… p. 57 Chapter 4: Understanding the Tea Party……………………………………… p. 58 Introduction……………………………………………………………………… p. 58 A three legged movement: Grassroots Tea Party organizations……………... p. 59 The Movement’s Deep Story…………………………………………………… p. -

After the Meltdown

Tulsa Law Review Volume 45 Issue 3 Regulation and Recession: Causes, Effects, and Solutions for Financial Crises Spring 2010 After the Meltdown Daniel J. Morrissey Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.utulsa.edu/tlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Daniel J. Morrissey, After the Meltdown, 45 Tulsa L. Rev. 393 (2013). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.utulsa.edu/tlr/vol45/iss3/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by TU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Tulsa Law Review by an authorized editor of TU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Morrissey: After the Meltdown AFTER THE MELTDOWN Daniel J. Morrissey* We will not go back to the days of reckless behavior and unchecked excess that was at the heart of this crisis, where too many were motivated only by the appetite for quick kills and bloated bonuses. -President Barack Obamal The window of opportunityfor reform will not be open for long .... -Princeton Economist Hyun Song Shin 2 I. INTRODUCTION: THE MELTDOWN A. How it Happened One year after the financial markets collapsed, President Obama served notice on Wall Street that society would no longer tolerate the corrupt business practices that had almost destroyed the world's economy. 3 In "an era of rapacious capitalists and heedless self-indulgence," 4 an "ingenious elite" 5 set up a credit regime based on improvident * A.B., J.D., Georgetown University; Professor and Former Dean, Gonzaga University School of Law. This article is dedicated to Professor Tom Holland, a committed legal educator and a great friend to the author. -

The Russian Laundromat Exposed

The Russian Laundromat Exposed Credit: Ion Preașcă/RISE Moldova by OCCRP 20 March 2017 (http://twitter.com/intent/tweet?status=The Russian Laundromat Exposed+https://www.occrp.org/en/laundromat/the-russian-laundromat-exposed (http://www.facebook.com/share.php?u=https://www.occrp.org/en/laundromat/the-russian-laundromat-exposed/&title=The Russian Laundromat E Donate (https://www.occrp.org/en/donate) Three years after the “Laundromat” was exposed as a criminal financial vehicle to move vast sums of money out of Russia, journalists now know how the complex scheme worked – including who ended up with the $20.8 billion and how, despite warnings, banks failed for years to shut it down. The Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) broke the story of the Laundromat in 2014, but recently the reporters from OCCRP and Novaya Gazeta in Moscow obtained a wealth of bank records which they then opened to investigative reporters in 32 countries. Their combined research for the first time paints a fuller picture of how billions moved from Russia, into and through the 112 bank accounts that comprised the system in eastern Europe, then into banks around the world. Reporters can now say that much of the money ultimately found its way to Russian businessmen who own groups of companies involved in construction, engineering, information technology, and banking. All held hundreds of millions of US dollars in state contracts either with the government directly, or with state-owned entities. They are named in this project and their spending sprees on fancy autos, prep school fees, furs, and electronics are revealed. -

Money Laundering Cases Involving Russian Individuals and Their Effect on the Eu”

29-01-2019 1 SPECIAL COMMITTEE ON FINANCIAL CRIMES, TAX EVASION AND TAX AVOIDANCE (TAX3) TUESDAY 29 JANUARY 2019 * * * PUBLIC HEARING “MONEY LAUNDERING CASES INVOLVING RUSSIAN INDIVIDUALS AND THEIR EFFECT ON THE EU” * * * Panel I: Effects in the EU of the money laundering cases involving Russian linkages Anders Åslund, Senior Fellow, Atlantic Council; Adjunct Professor, Georgetown University Joshua Kirschenbaum, Senior fellow at German Marshall Fund’s Alliance for Securing Democracy Richard Brooks, Financial investigative journalist for The Guardian and Private Eye magazine Panel II: The Magnitsky case Bill Browder, CEO and co-founder of Hermitage Capital Management Günter Schirmer, Head of the Secretariat of the Committee on Legal Affairs and Human Rights of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe 2 29-01-2019 1-002-0000 IN THE CHAIR: PETR JEŽEK Chair of the Special Committee on Financial Crimes, Tax Evasion and Tax Avoidance (The meeting opened at 14.38) Panel I: Effects in the EU of money laundering cases involving Russian linkages 1-004-0000 Chair. – Good afternoon dear colleagues, dear guests, Ladies and Gentlemen. Let us start the public hearing of the Special Committee on Financial Crimes, Tax Evasion and Tax Avoidance (TAX3) on money-laundering cases involving Russian individuals and their effects on the EU. We will deal with the issue in two panels. On the first panel we are going to discuss the effects on the EU of money-laundering cases involving Russian linkages. Let me now introduce the speakers for the first panel. We welcome Mr Anders Åslund, who is a Senior Fellow at the Atlantic Council and Adjunct Professor, Georgetown University. -

Americans for Tax Fairness Selected Opinion Pieces on Corporate Inversions

AMERICANS FOR TAX FAIRNESS SELECTED OPINION PIECES ON CORPORATE INVERSIONS As of October 1, 2014 NATIONAL Fortune – Positively un-American Tax Dodgers, Allan Sloan, July 7, 2014 “Undermining the finances of the federal government by inverting helps undermine our economy. And that’s a bad thing, in the long run, for companies that do business in America.” Fortune – Foreign Tax Ploys Raise a Question: What is an American Company?, Allan Sloan, June 2, 2014 “But in the past few years, as the world has become more global and other countries have cut their corporate rates, a new exodus wave has started. ‘For the past 20 years, there’s been an arms race between the companies on the one hand and the IRS and Congress on the other, and the companies always seem to come up with better weapons,’ says tax expert Bob Willens.” The New York Times – Cracking Down on Corporate Tax Games, The Editorial Board, September 23, 2014 “New rules from the Treasury Department[2] are likely to slow the offensive practice that allows American companies to avoid taxes by merging with foreign rivals. Known as corporate inversions, these are complex, modern variations on the practices of yesteryear, when companies dodged their taxes by moving their addresses to post office boxes in the Caribbean.” The New York Times – At Walgreen, Renouncing Corporate Citizenship, Andrew Ross Sorkin, June 30, 2014 “In Walgreen’s case, an inversion would be an affront to United States taxpayers. The company, which also owns the Duane Reade chain in New York, reaps almost a quarter of -

The Role of Derivatives in the Financial Crisis Testimony Of

The Role of Derivatives in the Financial Crisis Testimony of Michael Greenberger Law School Professor University of Maryland School of Law Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission Hearing Dirksen Senate Office Building, Room 538 Washington DC Wednesday, June 30, 2010, 9am EDT TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Table of Contents ........................................................................................................................ i Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 1 The History of Derivatives and Derivatives Market Regulation .......................................... 1 The Early Derivatives Market .......................................................................................... 1 The Origins and Purposes of the Commodity Exchange Act ........................................... 1 The Nature of Futures Contracts ..................................................................................... 2 The Contours of the Exchange Trading Requirement...................................................... 2 The Development and Characteristics of Swaps ............................................................. 3 Swaps and the CEA‟s Exchange Trading Requirement ................................................... 4 The Standardization of Swaps Through the ISDA Master Agreement ............................. 5 The CFTC‟s May 1998 Concept Release ......................................................................... 5 Pre-1998