Cass Sunstein and the Modern Regulatory State Ass Sunstein ’75, J.D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notes and Sources for Evil Geniuses: the Unmaking of America: a Recent History

Notes and Sources for Evil Geniuses: The Unmaking of America: A Recent History Introduction xiv “If infectious greed is the virus” Kurt Andersen, “City of Schemes,” The New York Times, Oct. 6, 2002. xvi “run of pedal-to-the-medal hypercapitalism” Kurt Andersen, “American Roulette,” New York, December 22, 2006. xx “People of the same trade” Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations, ed. Andrew Skinner, 1776 (London: Penguin, 1999) Book I, Chapter X. Chapter 1 4 “The discovery of America offered” Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy In America, trans. Arthur Goldhammer (New York: Library of America, 2012), Book One, Introductory Chapter. 4 “A new science of politics” Tocqueville, Democracy In America, Book One, Introductory Chapter. 4 “The inhabitants of the United States” Tocqueville, Democracy In America, Book One, Chapter XVIII. 5 “there was virtually no economic growth” Robert J Gordon. “Is US economic growth over? Faltering innovation confronts the six headwinds.” Policy Insight No. 63. Centre for Economic Policy Research, September, 2012. --Thomas Piketty, “World Growth from the Antiquity (growth rate per period),” Quandl. 6 each citizen’s share of the economy Richard H. Steckel, “A History of the Standard of Living in the United States,” in EH.net (Economic History Association, 2020). --Andrew McAfee and Erik Brynjolfsson, The Second Machine Age: Work, Progress, and Prosperity in a Time of Brilliant Technologies (New York: W.W. Norton, 2016), p. 98. 6 “Constant revolutionizing of production” Friedrich Engels and Karl Marx, Manifesto of the Communist Party (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1969), Chapter I. 7 from the early 1840s to 1860 Tomas Nonnenmacher, “History of the U.S. -

How America Lost Its Mind the Nation’S Current Post-Truth Moment Is the Ultimate Expression of Mind-Sets That Have Made America Exceptional Throughout Its History

1 How America Lost Its Mind The nation’s current post-truth moment is the ultimate expression of mind-sets that have made America exceptional throughout its history. KURT ANDERSEN SEPTEMBER 2017 ISSUE THE ATLANTIC “You are entitled to your own opinion, but you are not entitled to your own facts.” — Daniel Patrick Moynihan “We risk being the first people in history to have been able to make their illusions so vivid, so persuasive, so ‘realistic’ that they can live in them.” — Daniel J. Boorstin, The Image: A Guide to Pseudo-Events in America (1961) 1) WHEN DID AMERICA become untethered from reality? I first noticed our national lurch toward fantasy in 2004, after President George W. Bush’s political mastermind, Karl Rove, came up with the remarkable phrase reality-based community. People in “the reality-based community,” he told a reporter, “believe that solutions emerge from your judicious study of discernible reality … That’s not the way the world really works anymore.” A year later, The Colbert Report went on the air. In the first few minutes of the first episode, Stephen Colbert, playing his right-wing-populist commentator character, performed a feature called “The Word.” His first selection: truthiness. “Now, I’m sure some of the ‘word police,’ the ‘wordinistas’ over at Webster’s, are gonna say, ‘Hey, that’s not a word!’ Well, anybody who knows me knows that I’m no fan of dictionaries or reference books. They’re elitist. Constantly telling us what is or isn’t true. Or what did or didn’t happen. -

Download on the AASL Website an Anonymous Funder Donated $170,000 Tee, and the Rainbow Round Table at Bit.Ly/AASL-Statements

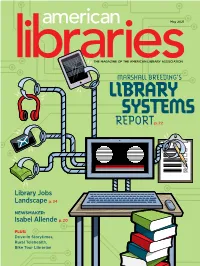

May 2021 THE MAGAZINE OF THE AMERICAN LIBRARY ASSOCIATION MARSHALL BREEDING’S LIBRARY SYSTEMS REPORTp. 22 Library Jobs Landscape p. 34 NEWSMAKER: Isabel Allende p. 20 PLUS: Drive-In Storytimes, Rural Telehealth, Bike Tour Librarian This Summer! Join us online at the event created and curated for the library community. Event Highlights • Educational programming • COVID-19 information for libraries • News You Can Use sessions highlighting • Interactive Discussion Groups new research and advances in libraries • Presidents' Programs • Memorable and inspiring featured authors • Livestreamed and on-demand sessions and celebrity speakers • Networking opportunities to share and The Library Marketplace with more than • connect with peers 250 exhibitors, Presentation Stages, Swag-A-Palooza, and more • Event content access for a full year ALA Members who have been recently furloughed, REGISTER TODAY laid o, or are experiencing a reduction of paid alaannual.org work hours are invited to register at no cost. #alaac21 Thank you to our Sponsors May 2021 American Libraries | Volume 52 #5 | ISSN 0002-9769 COVER STORY 2021 LIBRARY SYSTEMS REPORT Advancing library technologies in challenging times | p. 22 BY Marshall Breeding FEATURES 38 JOBS REPORT 34 The Library Employment Landscape Job seekers navigate uncertain terrain BY Anne Ford 38 The Virtual Job Hunt Here’s how to stand out, both as an applicant and an employer BY Claire Zulkey 42 Serving the Community at All Times Cultural inclusivity programming during a pandemic BY Nicanor Diaz, Virginia Vassar -

Print Hardcover Best Sellers

Copyright © 2017 October 1, 2017 by The New York Times THE NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW Print Hardcover Best Sellers THIS LAST WEEKS THIS LAST WEEKS WEEK WEEK Fiction ON LIST WEEK WEEK Nonfiction ON LIST A COLUMN OF FIRE, by Ken Follett. (Viking) The lovers Ned 1 WHAT HAPPENED, by Hillary Rodham Clinton. (Simon & 1 1 1 Willard and Margery Fitzgerald find themselves on opposite sides Schuster) The first woman nominated for president by a major of a conflict between English Catholics and Protestants while political party details her campaign, mistakes she made, outside Queen Elizabeth fights to maintain her throne. forces that affected the outcome and how she recovered in its aftermath. THE GIRL WHO TAKES AN EYE FOR AN EYE, by David 1 2 Lagercrantz. (Knopf) Lisbeth Salander teams up with an UNBELIEVABLE, by Katy Tur. (Dey St.) The NBC News 1 2 investigative journalist to uncover the secrets of her childhood. A correspondent describes her work covering the 2016 campaign continuation of Stieg Larsson’s Millennium series. of the Republican nominee for president and his behavior toward her. 3 ENEMY OF THE STATE, by Kyle Mills. (Atria/Emily Bestler) Vince 2 3 Flynn’s character Mitch Rapp leaves the C.I.A. to go on a manhunt 1 ASTROPHYSICS FOR PEOPLE IN A HURRY, by Neil deGrasse 20 3 when the nephew of a Saudi King finances a terrorist group. Tyson. (Norton) A straightforward, easy-to-understand introduction to the universe. THE ROMANOV RANSOM, by Clive Cussler and Robin Burcell. 1 4 (Putnam) Sam and Remi Fargo search for two missing filmmakers 2 HILLBILLY ELEGY, by J. -

How America Went Haywire

Have Smartphones Why Women Bully Destroyed a Each Other at Work Generation? p. 58 BY OLGA KHAZAN Conspiracy Theories. Fake News. Magical Thinking. How America Went Haywire By Kurt Andersen The Rise of the Violent Left Jane Austen Is Everything The Whitest Music Ever John le Carré Goes SEPTEMBER 2017 Back Into the Cold THEATLANTIC.COM 0917_Cover [Print].indd 1 7/19/2017 1:57:09 PM TerTeTere msm appppply.ly Viistsits ameierier cancaanexpexpresre scs.cs.s com/om busbubusinesspsplatl inuummt to learnmn moreorer . Hogarth &Ogilvy Hogarth 212.237.7000 CODE: FILE: DESCRIPTION: 29A-008875-25C-PBC-17-238F.indd PBC-17-238F TAKE A BREAK BEFORE TAKING ONTHEWORLD ABREAKBEFORETAKING TAKE PUB/POST: The Atlantic -9/17issue(Due TheAtlantic SAP #: #: WORKORDER PRODUCTION: AP.AP PBC.17020.K.011 AP.AP al_stacked_l_18in_wide_cmyk.psd Art: D.Hanson AP17006A_003C_EarlyCheckIn_SWOP3.tif 008875 BLEED: TRIM: LIVE: (CMYK; 3881 ppi; Up toDate) (CMYK; 3881ppi;Up 15.25” x10” 15.75”x10.5” 16”x10.75” (CMYK; 908 ppi; Up toDate), (CMYK; 908ppi;Up 008875-13A-TAKE_A_BREAK_CMYK-TintRev.eps 008875-13A-TAKE_A_BREAK_CMYK-TintRev.eps (Up toDate), (Up AP- American Express-RegMark-4C.ai AP- AmericanExpress-RegMark-4C.ai (Up toDate), (Up sbs_fr_chg_plat_met- at americanexpress.com/exploreplatinum at PlatinumMembership Business of theworld Explore FineHotelsandResorts. hand-picked 975 atover head your andclear early Arrive TerTeTere msm appppply.ly Viistsits ameierier cancaanexpexpresre scs.cs.s com/om busbubusinesspsplatl inuummt to learnmn moreorer . Hogarth &Ogilvy Hogarth 212.237.7000 -

Some Major Advertisers Step up the Pressure on Magazines to Alter Their Content, Will Editors Bend?

THE by Russ Baker SOME MAJOR ADVERTISERS STEP UP THE PRESSURE ON MAGAZINES TO ALTER THEIR CONTENT, WILL EDITORS BEND? In an effort to avoid potential conflicts, s there any doubt that advertisers reason to hope that other advertisers it is required that Chrysler Corporation mumble and sometimes roar about won’t ask for the same privilege. be alerted in advance of any and all edi- reporting that can hurt them? You will have thirty or forty adver- torial content that encompasses sexual, I That the auto giants don’t like tisers checking through the pages. political, social issues or any editorial pieces that, say point to auto safety They will send notes to publishers. that might be construed as provocative problems? Or that Big Tobacco hates I don’t see how any good citizen or offensive. Each and every issue that to see its glamorous, cheerful ads doesn’t rise to this occasion and say carries Chrysler advertising requires a juxtaposed with articles mentioning this development is un-American Written summary outlining major their best customers’ grim way of and a threat to freedom.” theme/articles appearing in upcoming death? When advertisers disapprove Hyperbole? Maybe not. Just about issues. These summaries are to be for- of an editorial climate, they can- any editor will tell you: the ad/edit Warded to PentaCorn prior to closing in and sometimes do take a hike. chemistry is changing for the worse. order to give Ch ysler ample time to re- But for Chrysler to push beyond Corporations and their ad agencies view and reschedule if desired. -

Intelligence Squared U.S. Trump Is Bad for Comedy

Intelligence Squared U.S. 1 November 1, 2018 November 1, 2018 Ray Padgett | [email protected] Mark Satlof | [email protected] T: 718.522.7171 Intelligence Squared U.S. Trump Is Bad for Comedy For the Motion: P. J. O’Rourke, Sara Schaefer Against the Motion: Kurt Andersen, Billy Kimball Moderator: John Donvan AUDIENCE RESULTS Before the debate: After the debate: 35% FOR 37% FOR 42% AGAINST 54% AGAINST 23% UNDECIDED 9% UNDECIDED 00:00:00 [music playing] [applause] John Donvan: There has always been political humor. It has always been part of the political discourse while serving several functions at one time, from truth telling to catharsis and also, ideally, it's supposed to be funny, which brings us to the present moment. With the sharp spike that we are all seeing in comedy that is focused on politics, and especially on the man who currently occupies the Oval Office, we have all of those late night monologues, the satirical cable shows, the columns and the podcasts, and, of course, everybody and his brother is doing a Trump impersonation. But this spike in comedy, how sharp, comically speaking, is it really? Now, when we are so very Prepared by National Capitol Contracting 8255 Greensboro Drive, Suite C100 (703) 243-9696 McLean, VA 22102 Intelligence Squared U.S. 2 November 1, 2018 polarized, how good and how successful is comedy at this moment, not just in getting us to think, but also in getting us to laugh? Well, we think this has the makings of a debate, so let's have it. -

TBT Sep-Oct 2018 for Online

Talking Book Topics September–October 2018 Volume 84, Number 5 Need help? Your local cooperating library is always the place to start. For general information and to order books, call 1-888-NLS-READ (1-888-657-7323) to be connected to your local cooperating library. To find your library, visit www.loc.gov/nls and select “Find Your Library.” To change your Talking Book Topics subscription, contact your local cooperating library. Get books fast from BARD Most books and magazines listed in Talking Book Topics are available to eligible readers for download on the NLS Braille and Audio Reading Download (BARD) site. To use BARD, contact your local cooperating library or visit nlsbard.loc.gov for more information. The free BARD Mobile app is available from the App Store, Google Play, and Amazon’s Appstore. About Talking Book Topics Talking Book Topics, published in audio, large print, and online, is distributed free to people unable to read regular print and is available in an abridged form in braille. Talking Book Topics lists titles recently added to the NLS collection. The entire collection, with hundreds of thousands of titles, is available at www.loc.gov/nls. Select “Catalog Search” to view the collection. Talking Book Topics is also online at www.loc.gov/nls/tbt and in downloadable audio files from BARD. Overseas Service American citizens living abroad may enroll and request delivery to foreign addresses by contacting the NLS Overseas Librarian by phone at (202) 707-9261 or by email at [email protected]. Page 1 of 87 Music scores and instructional materials NLS music patrons can receive braille and large-print music scores and instructional recordings through the NLS Music Section. -

(7Be5e32) PDF Evil Geniuses: the Unmaking of America: a Recent

PDF Evil Geniuses: The Unmaking Of America: A Recent History Kurt Andersen - pdf free book Evil Geniuses: The Unmaking Of America: A Recent History PDF, Evil Geniuses: The Unmaking Of America: A Recent History by Kurt Andersen Download, Read Evil Geniuses: The Unmaking Of America: A Recent History Full Collection Kurt Andersen, Evil Geniuses: The Unmaking Of America: A Recent History Full Collection, Read Best Book Online Evil Geniuses: The Unmaking Of America: A Recent History, PDF Evil Geniuses: The Unmaking Of America: A Recent History Free Download, Read Online Evil Geniuses: The Unmaking Of America: A Recent History Ebook Popular, PDF Evil Geniuses: The Unmaking Of America: A Recent History Full Collection, online free Evil Geniuses: The Unmaking Of America: A Recent History, pdf download Evil Geniuses: The Unmaking Of America: A Recent History, read online free Evil Geniuses: The Unmaking Of America: A Recent History, Evil Geniuses: The Unmaking Of America: A Recent History Kurt Andersen pdf, Kurt Andersen ebook Evil Geniuses: The Unmaking Of America: A Recent History, Download Evil Geniuses: The Unmaking Of America: A Recent History E-Books, Download pdf Evil Geniuses: The Unmaking Of America: A Recent History, Download Evil Geniuses: The Unmaking Of America: A Recent History Online Free, Read Online Evil Geniuses: The Unmaking Of America: A Recent History Book, Evil Geniuses: The Unmaking Of America: A Recent History Popular Download, Evil Geniuses: The Unmaking Of America: A Recent History Read Download, Free Download Evil Geniuses: The Unmaking Of America: A Recent History Books [E-BOOK] Evil Geniuses: The Unmaking Of America: A Recent History Full eBook, CLICK TO DOWNLOAD But i am always looking for something new to read. -

Brooklyn Public Library Announces In-Person & Virtual Fall 2020 Arts

Brooklyn Public Library Announces In-Person & Virtual Fall 2020 Arts and Cultural Programming Highlights include: • The release of the 28th Amendment Project’s crowd-sourced proposed amendment to the U.S. Constitution from members of the Brooklyn community, along with accompanying in-person and digital programming • American Civil Liberties Union President Susan Herman presenting the 2020 Kahn Humanities Lecture on COVID-19 in a time of constitutional crisis • Choreographer, director, and author Bill T. Jones delivers the fifth BPL-commissioned Message from the Library the week of the Presidential election • The launch of Whispering Libraries – curated outdoor playlists across Brooklyn to inspire and uplift the community • Peabody Award winner Kurt Andersen, best-selling author and historian Jill Lepore, Politico journalist Dan C. Goldberg, and more discuss their latest literary works • The return of Library favorites – University Open Air outdoors in Prospect Park, a digital iteration of LitFilm: A BPL Film Festival About Writers, musical offerings, and more Brooklyn, NY— August 26, 2020— Brooklyn Public Library (BPL) today unveiled its 2020 BPL Presents fall season, a series of free cultural programming that provides myriad opportunities for engagement from the community. Season highlights include the return of University Open Air’s outdoor classes, in partnership with Prospect Park Alliance and the launch of Whispering Libraries, which offers snippets of literary classics, oral histories and inspiring tales which can be heard outside Library branches and small speakers attached to bicycles pedaled by a group of riders. Additional highlights include a presentation by choreographer, director, and author Bill T. Jones, who will digitally deliver the BPL- commissioned Message from the Library five days after the Presidential election; and Susan Herman, President of the American Civil Liberties Union, who will present the 2020 Kahn Humanities Lecture on COVID-19 and the Constitution. -

Fall-2017-Catalog1.Pdf

Fall 2017 Autumn/Karl Ove Knausgaard Little Fires Everywhere/Celeste Ng World Without Mind/Franklin Foer Americana/Bhu Srinivasan Devotions/Mary Oliver Grant/Ron Chernow Stalin/Stephen Kotkin Soonish/Zach Weinersmith and Kelly Weinersmith Meetings with Remarkable Manuscripts/Christopher de Hamel You Can’t Spell America Without Me/Alec Baldwin and Kurt Andersen Playing with Fire/Lawrence O’Donnell Friends Divided/Gordon S. Wood The Dawn Watch/Maya Jasanoff The Infinite Future/Tim Wirkus Cover image: © Qusai Akoud AUTUMN KARL OVE KNAUSGAARD isbn: 9780399563300 price: $27.00 on sale: 8/22/2017 AUTUMN KARL OVE KNAUSGAARD From the author of the monumental My Struggle series, Karl Ove Knausgaard, one of the masters of contemporary literature and a genius of observation and introspection, comes the first in a new autobiographical quartet based on the four seasons. 28 August. Now, as I write this, you know nothing about with the precision and mesmerizing intensity anything, about what awaits you, the kind of world you will be that have become his trademark. He describes born into. And I know nothing about you... with acute sensitivity daily life with his wife and I want to show you our world as it is now: the door, the children in rural Sweden, drawing upon memories floor, the water tap and the sink, the garden chair close to the of his own childhood to give an inimitably tender wall beneath the kitchen window, the sun, the water, the trees. perspective on the precious and unique bond You will come to see it in your own way, you will experience between parent and child. -

Wealth, Lobbying and Distributive Justice in the Wake of the Economic Crisis C.M.A

DIDN'T YOUR MOTHER TEACH YOU TO SHARE?*: WEALTH, LOBBYING AND DISTRIBUTIVE JUSTICE IN THE WAKE OF THE ECONOMIC CRISIS C.M.A. Mc Cauliff* *SELFISH OR SHARING? . .... .. 383 **ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .............................. ...... 383 * Yaron Brook, president of the Ayn Rand Institute, finds problems with what he calls "governmental influence, where 'somebody's need is a claim against our wealth."' As he sees it, "[t]he last 50 years have been an orgy of placing need above wealth creation, above personal pursuit of happiness." Andrew Martin, Give BB&T Liberty, But Not a Bailout, N.Y. TIMES, Aug. 2, 2009, at BU1 (explaining the views of followers of Ayn Rand, a refugee from communist Russia who proclaimed herself a radical for capitalism). Explaining this viewpoint, a speaker at a recent Ayn Rand convention told the story of a boy in the sandbox, who fights with another child who had taken the boy's toy truck. The boy's mother naturally stops him from fighting by telling him to share the use of the toy. The speaker says "that the mother has taught a horrible lesson" by implying that it is "bad to be selfish." Id. He concludes that "[t]o say man is bad because he is selfish is to say it's bad because he's alive." Id. (Presumably, the mother would still be able to stop the child from touching the metal pot on the stove or picking up a shiny knife.) The speaker, John A. Allison IV, is a banker whose bank BB&T, the eleventh largest bank, had problems during the financial crisis, but Allison insists that the government forced BB&T "to accept TARP money to obscure that [the government was] simply trying to save several large banks like Citigroup." Id.