Transcript of Interview with Oskar Eustis on Studio 360 with Kurt

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The 200 Plays That Every Theatre Major Should Read

The 200 Plays That Every Theatre Major Should Read Aeschylus The Persians (472 BC) McCullers A Member of the Wedding The Orestia (458 BC) (1946) Prometheus Bound (456 BC) Miller Death of a Salesman (1949) Sophocles Antigone (442 BC) The Crucible (1953) Oedipus Rex (426 BC) A View From the Bridge (1955) Oedipus at Colonus (406 BC) The Price (1968) Euripdes Medea (431 BC) Ionesco The Bald Soprano (1950) Electra (417 BC) Rhinoceros (1960) The Trojan Women (415 BC) Inge Picnic (1953) The Bacchae (408 BC) Bus Stop (1955) Aristophanes The Birds (414 BC) Beckett Waiting for Godot (1953) Lysistrata (412 BC) Endgame (1957) The Frogs (405 BC) Osborne Look Back in Anger (1956) Plautus The Twin Menaechmi (195 BC) Frings Look Homeward Angel (1957) Terence The Brothers (160 BC) Pinter The Birthday Party (1958) Anonymous The Wakefield Creation The Homecoming (1965) (1350-1450) Hansberry A Raisin in the Sun (1959) Anonymous The Second Shepherd’s Play Weiss Marat/Sade (1959) (1350- 1450) Albee Zoo Story (1960 ) Anonymous Everyman (1500) Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf Machiavelli The Mandrake (1520) (1962) Udall Ralph Roister Doister Three Tall Women (1994) (1550-1553) Bolt A Man for All Seasons (1960) Stevenson Gammer Gurton’s Needle Orton What the Butler Saw (1969) (1552-1563) Marcus The Killing of Sister George Kyd The Spanish Tragedy (1586) (1965) Shakespeare Entire Collection of Plays Simon The Odd Couple (1965) Marlowe Dr. Faustus (1588) Brighton Beach Memoirs (1984 Jonson Volpone (1606) Biloxi Blues (1985) The Alchemist (1610) Broadway Bound (1986) -

Notes and Sources for Evil Geniuses: the Unmaking of America: a Recent History

Notes and Sources for Evil Geniuses: The Unmaking of America: A Recent History Introduction xiv “If infectious greed is the virus” Kurt Andersen, “City of Schemes,” The New York Times, Oct. 6, 2002. xvi “run of pedal-to-the-medal hypercapitalism” Kurt Andersen, “American Roulette,” New York, December 22, 2006. xx “People of the same trade” Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations, ed. Andrew Skinner, 1776 (London: Penguin, 1999) Book I, Chapter X. Chapter 1 4 “The discovery of America offered” Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy In America, trans. Arthur Goldhammer (New York: Library of America, 2012), Book One, Introductory Chapter. 4 “A new science of politics” Tocqueville, Democracy In America, Book One, Introductory Chapter. 4 “The inhabitants of the United States” Tocqueville, Democracy In America, Book One, Chapter XVIII. 5 “there was virtually no economic growth” Robert J Gordon. “Is US economic growth over? Faltering innovation confronts the six headwinds.” Policy Insight No. 63. Centre for Economic Policy Research, September, 2012. --Thomas Piketty, “World Growth from the Antiquity (growth rate per period),” Quandl. 6 each citizen’s share of the economy Richard H. Steckel, “A History of the Standard of Living in the United States,” in EH.net (Economic History Association, 2020). --Andrew McAfee and Erik Brynjolfsson, The Second Machine Age: Work, Progress, and Prosperity in a Time of Brilliant Technologies (New York: W.W. Norton, 2016), p. 98. 6 “Constant revolutionizing of production” Friedrich Engels and Karl Marx, Manifesto of the Communist Party (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1969), Chapter I. 7 from the early 1840s to 1860 Tomas Nonnenmacher, “History of the U.S. -

How America Lost Its Mind the Nation’S Current Post-Truth Moment Is the Ultimate Expression of Mind-Sets That Have Made America Exceptional Throughout Its History

1 How America Lost Its Mind The nation’s current post-truth moment is the ultimate expression of mind-sets that have made America exceptional throughout its history. KURT ANDERSEN SEPTEMBER 2017 ISSUE THE ATLANTIC “You are entitled to your own opinion, but you are not entitled to your own facts.” — Daniel Patrick Moynihan “We risk being the first people in history to have been able to make their illusions so vivid, so persuasive, so ‘realistic’ that they can live in them.” — Daniel J. Boorstin, The Image: A Guide to Pseudo-Events in America (1961) 1) WHEN DID AMERICA become untethered from reality? I first noticed our national lurch toward fantasy in 2004, after President George W. Bush’s political mastermind, Karl Rove, came up with the remarkable phrase reality-based community. People in “the reality-based community,” he told a reporter, “believe that solutions emerge from your judicious study of discernible reality … That’s not the way the world really works anymore.” A year later, The Colbert Report went on the air. In the first few minutes of the first episode, Stephen Colbert, playing his right-wing-populist commentator character, performed a feature called “The Word.” His first selection: truthiness. “Now, I’m sure some of the ‘word police,’ the ‘wordinistas’ over at Webster’s, are gonna say, ‘Hey, that’s not a word!’ Well, anybody who knows me knows that I’m no fan of dictionaries or reference books. They’re elitist. Constantly telling us what is or isn’t true. Or what did or didn’t happen. -

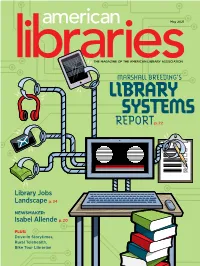

Download on the AASL Website an Anonymous Funder Donated $170,000 Tee, and the Rainbow Round Table at Bit.Ly/AASL-Statements

May 2021 THE MAGAZINE OF THE AMERICAN LIBRARY ASSOCIATION MARSHALL BREEDING’S LIBRARY SYSTEMS REPORTp. 22 Library Jobs Landscape p. 34 NEWSMAKER: Isabel Allende p. 20 PLUS: Drive-In Storytimes, Rural Telehealth, Bike Tour Librarian This Summer! Join us online at the event created and curated for the library community. Event Highlights • Educational programming • COVID-19 information for libraries • News You Can Use sessions highlighting • Interactive Discussion Groups new research and advances in libraries • Presidents' Programs • Memorable and inspiring featured authors • Livestreamed and on-demand sessions and celebrity speakers • Networking opportunities to share and The Library Marketplace with more than • connect with peers 250 exhibitors, Presentation Stages, Swag-A-Palooza, and more • Event content access for a full year ALA Members who have been recently furloughed, REGISTER TODAY laid o, or are experiencing a reduction of paid alaannual.org work hours are invited to register at no cost. #alaac21 Thank you to our Sponsors May 2021 American Libraries | Volume 52 #5 | ISSN 0002-9769 COVER STORY 2021 LIBRARY SYSTEMS REPORT Advancing library technologies in challenging times | p. 22 BY Marshall Breeding FEATURES 38 JOBS REPORT 34 The Library Employment Landscape Job seekers navigate uncertain terrain BY Anne Ford 38 The Virtual Job Hunt Here’s how to stand out, both as an applicant and an employer BY Claire Zulkey 42 Serving the Community at All Times Cultural inclusivity programming during a pandemic BY Nicanor Diaz, Virginia Vassar -

Print Hardcover Best Sellers

Copyright © 2017 October 1, 2017 by The New York Times THE NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW Print Hardcover Best Sellers THIS LAST WEEKS THIS LAST WEEKS WEEK WEEK Fiction ON LIST WEEK WEEK Nonfiction ON LIST A COLUMN OF FIRE, by Ken Follett. (Viking) The lovers Ned 1 WHAT HAPPENED, by Hillary Rodham Clinton. (Simon & 1 1 1 Willard and Margery Fitzgerald find themselves on opposite sides Schuster) The first woman nominated for president by a major of a conflict between English Catholics and Protestants while political party details her campaign, mistakes she made, outside Queen Elizabeth fights to maintain her throne. forces that affected the outcome and how she recovered in its aftermath. THE GIRL WHO TAKES AN EYE FOR AN EYE, by David 1 2 Lagercrantz. (Knopf) Lisbeth Salander teams up with an UNBELIEVABLE, by Katy Tur. (Dey St.) The NBC News 1 2 investigative journalist to uncover the secrets of her childhood. A correspondent describes her work covering the 2016 campaign continuation of Stieg Larsson’s Millennium series. of the Republican nominee for president and his behavior toward her. 3 ENEMY OF THE STATE, by Kyle Mills. (Atria/Emily Bestler) Vince 2 3 Flynn’s character Mitch Rapp leaves the C.I.A. to go on a manhunt 1 ASTROPHYSICS FOR PEOPLE IN A HURRY, by Neil deGrasse 20 3 when the nephew of a Saudi King finances a terrorist group. Tyson. (Norton) A straightforward, easy-to-understand introduction to the universe. THE ROMANOV RANSOM, by Clive Cussler and Robin Burcell. 1 4 (Putnam) Sam and Remi Fargo search for two missing filmmakers 2 HILLBILLY ELEGY, by J. -

How America Went Haywire

Have Smartphones Why Women Bully Destroyed a Each Other at Work Generation? p. 58 BY OLGA KHAZAN Conspiracy Theories. Fake News. Magical Thinking. How America Went Haywire By Kurt Andersen The Rise of the Violent Left Jane Austen Is Everything The Whitest Music Ever John le Carré Goes SEPTEMBER 2017 Back Into the Cold THEATLANTIC.COM 0917_Cover [Print].indd 1 7/19/2017 1:57:09 PM TerTeTere msm appppply.ly Viistsits ameierier cancaanexpexpresre scs.cs.s com/om busbubusinesspsplatl inuummt to learnmn moreorer . Hogarth &Ogilvy Hogarth 212.237.7000 CODE: FILE: DESCRIPTION: 29A-008875-25C-PBC-17-238F.indd PBC-17-238F TAKE A BREAK BEFORE TAKING ONTHEWORLD ABREAKBEFORETAKING TAKE PUB/POST: The Atlantic -9/17issue(Due TheAtlantic SAP #: #: WORKORDER PRODUCTION: AP.AP PBC.17020.K.011 AP.AP al_stacked_l_18in_wide_cmyk.psd Art: D.Hanson AP17006A_003C_EarlyCheckIn_SWOP3.tif 008875 BLEED: TRIM: LIVE: (CMYK; 3881 ppi; Up toDate) (CMYK; 3881ppi;Up 15.25” x10” 15.75”x10.5” 16”x10.75” (CMYK; 908 ppi; Up toDate), (CMYK; 908ppi;Up 008875-13A-TAKE_A_BREAK_CMYK-TintRev.eps 008875-13A-TAKE_A_BREAK_CMYK-TintRev.eps (Up toDate), (Up AP- American Express-RegMark-4C.ai AP- AmericanExpress-RegMark-4C.ai (Up toDate), (Up sbs_fr_chg_plat_met- at americanexpress.com/exploreplatinum at PlatinumMembership Business of theworld Explore FineHotelsandResorts. hand-picked 975 atover head your andclear early Arrive TerTeTere msm appppply.ly Viistsits ameierier cancaanexpexpresre scs.cs.s com/om busbubusinesspsplatl inuummt to learnmn moreorer . Hogarth &Ogilvy Hogarth 212.237.7000 -

Beautiful Family! Broadway/ First National Tour: Beautiful; Betty/ Ensemble

SARAH BOCKEL (Carole King) is thrilled to be back on the road with her Beautiful family! Broadway/ First National Tour: Beautiful; Betty/ Ensemble. Regional: Million Dollar Quartet (Chicago); u/s Dyanne. Rocky Mountain Repertory Theatre- Les Mis; Madame Thenardier. Shrek; Dragon. Select Chicago credits: Bohemian Theatre Ensemble; Parade, Lucille (Non-eq Jeff nomination) The Hypocrites; Into the Woods, Cinderella/ Rapunzel. Haven Theatre; The Wedding Singer, Holly. Paramount Theatre; Fiddler on the Roof, ensemble. Illinois Wesleyan University SoTA Alum. Proudly represented by Stewart Talent Chicago. Many thanks to the Beautiful creative team and her superhero agents Jim and Sam. As always, for Mom and Dad. ANDREW BREWER (Gerry Goffin) Broadway/Tour: Beautiful (Swing/Ensemble u/s Gerry/Don) Off-Broadway: Sex Tips for Straight Women from a Gay Man, Cougar the Musical, Nymph Errant. Love to my amazing family, The Mine, the entire Beautiful team! SARAH GOEKE (Cynthia Weil) is elated to be joining the touring cast of Beautiful - The Carole King Musical. Originally from Cape Girardeau, Missouri, she has a BM in vocal performance from the UMKC Conservatory and an MFA in Acting from Michigan State University. Favorite roles include, Sally in Cabaret, Judy/Ginger in Ruthless! the Musical, and Svetlana in Chess. Special thanks to her vital and inspiring family, friends, and soon-to-be husband who make her life Beautiful. www.sarahgoeke.com JACOB HEIMER (Barry Mann) Theater: Soul Doctor (Off Broadway), Milk and Honey (York/MUFTI), Twelfth Night (Elm Shakespeare), Seminar (W.H.A.T.), Paloma (Kitchen Theatre), Next to Normal (Music Theatre CT), and a reading of THE VISITOR (Daniel Sullivan/The Public). -

Some Major Advertisers Step up the Pressure on Magazines to Alter Their Content, Will Editors Bend?

THE by Russ Baker SOME MAJOR ADVERTISERS STEP UP THE PRESSURE ON MAGAZINES TO ALTER THEIR CONTENT, WILL EDITORS BEND? In an effort to avoid potential conflicts, s there any doubt that advertisers reason to hope that other advertisers it is required that Chrysler Corporation mumble and sometimes roar about won’t ask for the same privilege. be alerted in advance of any and all edi- reporting that can hurt them? You will have thirty or forty adver- torial content that encompasses sexual, I That the auto giants don’t like tisers checking through the pages. political, social issues or any editorial pieces that, say point to auto safety They will send notes to publishers. that might be construed as provocative problems? Or that Big Tobacco hates I don’t see how any good citizen or offensive. Each and every issue that to see its glamorous, cheerful ads doesn’t rise to this occasion and say carries Chrysler advertising requires a juxtaposed with articles mentioning this development is un-American Written summary outlining major their best customers’ grim way of and a threat to freedom.” theme/articles appearing in upcoming death? When advertisers disapprove Hyperbole? Maybe not. Just about issues. These summaries are to be for- of an editorial climate, they can- any editor will tell you: the ad/edit Warded to PentaCorn prior to closing in and sometimes do take a hike. chemistry is changing for the worse. order to give Ch ysler ample time to re- But for Chrysler to push beyond Corporations and their ad agencies view and reschedule if desired. -

Member/Audience Play Suggestions 2012-13

CURTAIN PLAYERS 2012-2013 plays suggested by patrons/members Title Author A Poetry Reading (Love Poetry for Valentines Day) Agnes of God All My Sons (by 3 people) Arthur Miller All The Way Home Tad Mosel Angel Street Anything by Pat Cook Pat Cook Apartment 3A Jeff Daniels Arcadia Tom Stoppard As Bees in Honey Drown Assassins Baby With The Bathwater (by 2 people) Christopher Durang Beyond Therapy Christopher Durang Bleacher Bums Blythe Spirit (by 2 people) Noel Coward Butterscotch Cash on Delivery Close Ties Crimes of the Heart Beth Henley Da Hugh Leonard Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (by 2 people) Jeffrey Hatcher Driving Miss Daisy Equus Peter Shaffer Farragut North Beau Willimon Frankie and Johnny in the Claire De Lune Terrence McNally God's Country Happy Birthday, Wanda June Kurt Vonnegut I Never Saw Another Butterfly Impressionism Michael Jacobs Laramie Project Leaving Iowa Tim Clue/Spike Manton Lettice and Lovage (by 2 people) Lombardi Eric Simonson LuAnn Hampton Laverty Oberlander Mr and Mrs Fitch Douglas Carter Beane 1 Night Mother No Exit Sartre Picnic William Inge Prelude to A Kiss (by 2 people) Craig Lucas Proof Red John Logan Ridiculous Fraud Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead (by 2 people) Tom Stoppard Sabrina Fair Samuel Taylor Second Samuel Pamela Parker She Loves Me Sheer Madness Side Man Warren Leight Sin Sister Mary Ignatius/Actor's Nightmare Christopher Durang Smoke on the Mountain (by 3 people) That Championship Season Jason Miller The 1940's Radio Hour Walton Jones The Caine Mutiny Court Martial The Cinderella Waltz The Country Girl Clifford Odets The Heidi Chronicles The Increased Difficulty of Concentration Vaclav Havel The Little Foxes Lillian Hellman The Man Who Came To Dinner Kaufman and Hart The Miser Moliere The Normal Heart Larry Kramer The Odd Couple Neil Simon The Passion of Dracula The Royal Family Kaufman and Ferber The Shape of Things LaBute The Substance of Fire Jon Robin Baitz The Tempest Shakespeare The Woolgatherer Three Days of Rain Richard Greenberg Tobacco Road While The Lights Were Out Wit 2 3 . -

List of Plays for Lobby Vertical

49 Seasons of Performing Arts of Woodstock, Inc. The Lesson (Launched PAW. Directed by Edith LeFever at the Cafe Espresso 1963 prior to PAW's incorporation. Holly Beye wrote a great review.) The Audience (new play by Danny Klein, directed by Edith LeFever) May 1964 Aria Da Capo The American Dream Dec 1964 The Happy Journey to Camden and Trenton Spoon River Anthology June 1966 Antigone (by Anouilh, directed by Edith LeFever) June 1966 The White Angel (new play by Holly Beye) Nov 1966 Postcards; The Bench (new plays by James Prideaux) May 1967 Banana Thief (new play by Holly Beye) Mar 1968 The Beholder (new play by Christopher Jones) July 1968 Charles, the Child Beautiful (new play by Danny Klein) As I Lay Dying (dramatization by Ron Radice) Jan 1969 Riders to the Sea Oct 1969 Adam + One Dec 1969 The Gem of the Ocean; Pickpocket (new plays by Ron Radice) Mar 1970 Miss Julie July 1970 Brecht on Brecht Nov 1970 From Rags to Riches Dec 1970 Late for Oblivion: Eurydice; The Maiden from the Eleventh Heaven ; Spring 1971 How Thunder and Lightening Began (new plays by Holly Beye) Three Men on a Horse (directed by Jo Chalmers) Aug 1971 Meanwhile in Beautiful Downtown Woodstock (new revue-Canadian material) Dec 1971 The End of Albert Englander (new play by John LeFever) Jan 1972 Major Barbara Feb 1972 Five Light Pieces from the World of Jean Tardieu June 1972 Once Again and Yet Again: Night; Eve (new plays by Marcia Haufrecht) Oct 1972 Rosa Rio and the Man Who Had Everything (new play by Marshall Yaeger) I Am a Camera Mar 1973 Under Milkwood May -

Exorcismprogram Lr.Pdf

PROUD SPONSOR OF SOUTH CAMDEN THEATRE COMPANY! Since 1923 Pub & Grill Serving appetizers, dinner, salads, sandwiches, desserts and a wide range of beer, wine and cocktails 401 N. Broadway Gloucester City, NJ 08030 856.456.3838 Monday-Saturday: 10am - 2am Sunday: 12pm - 11pm Visit us after the show. We’re easy to find. Simply turn right on Broadway toward the Walt Whitman Bridge. We’re 1.4 miles on the right. Producing Artistic Director Joseph M. Paprzycki and CAMDEN’S “OFF-BROADWAY” THEATRE P RESENTS DIRECTED BY JOSEPH M. PAPRZYCKI JANUARY 18, 19, 20 SOUTH CAMDEN THEATRE COMPANY W ATERFRONT SOUTH Theatre 400 Jasper Street, Camden, N.J. 08104 www.southcamdentheatre.org Live within walking distance to the Waterfront South Theatre! (A growing arts neighborhood.) Buy a fully renovated Heart of Camden home with a monthly mortgage as low as $550. Beautifully renovated, must-see homes 3 Bedrooms • 1 1/2 Baths • Appliance Package Call today: 856-966-1212 Find more information online at: www.heartofcamden.org and on Facebook TENN XTEN A CELEBRATION OF TENNESSEE WILLIAMS T ennessee’s Final Curtain, 2012 TENN XTEN A CELEBRATION OF TENNESSEE WILLIAMS The Night of the Iguana, 2012 TENN XTEN A CELEBRATION OF TENNESSEE WILLIAMS Suddenly Last Summer, 2011 TENN XTEN A CELEBRATION OF TENNESSEE WILLIAMS The Case of the Crushed Petunias, 2012 SOUTH CAMDEN THEATRE COMPANY Anchoring a neighborhood rebirth S PECIAL THANKS BOARD OF DIRECTORS Pepe Piperno and the Domenica Foundation J OSEPH M. PaPRZYCKI Producing Artistic Director Father Michael Doyle and the Sacred Heart Church Parish ROBERT BINGAMAN Helene Pierson and Heart of Camden Trustee, President Brother Mickey McGrath for his artwork LISA DEL DUKE Robert Allan & Associates, Inc. -

Cass Sunstein and the Modern Regulatory State Ass Sunstein ’75, J.D

The Legal Olympian Cass Sunstein and the modern regulatory state ass sunstein ’75, J.D. ’78, has been regarded as one of the country’s Cmost influential and adven- turous legal scholars for a generation. His scholarly ar- ticles have been cited more often than those of any of his peers ever since he was a young professor. At 60, now Walmsley University Profes- sor at Harvard Law School, he publishes significant books as often as many pro- ductive academics publish scholarly articles—three of them last year. In each, by Lincoln Caplan Sunstein comes across as a brainy and cheerful tech- nocrat, practiced at thinking about the consequenc- es of rules, regulations, and policies, with attention to the linkages between particular means and ends. Drawing on insights from cognitive psychology as well as behavioral economics, he is especially focused on mastering how people make significant choices that promote or undercut their own well-being and that of society, so government and other institutions can reinforce the good and correct for the bad in shaping policy. The first book,Valuing Life: Humanizing the Regulatory State, answers a question about him posed by Eric Posner, a professor of law, a friend of Sunstein’s, and a former colleague at the University of Chicago: “What happens when the world’s leading academic expert on regu- lation is plunked into the real world of government?” In “the cockpit of the regulatory state,” as Sunstein describes the White House Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs, which he led from 2009 to 2012, he oversaw the process of approving regulations for everything from food and financial services to healthcare and national security.