Mobility and the Representation of African Dystopian Spaces in Film and Literature a Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of Th

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

0 0 0 0 Acasa Program Final For

PROGRAM ABSTRACTS FOR THE 15TH TRIENNIAL SYMPOSIUM ON AFRICAN ART Africa and Its Diasporas in the Market Place: Cultural Resources and the Global Economy The core theme of the 2011 ACASA symposium, proposed by Pamela Allara, examines the current status of Africa’s cultural resources and the influence—for good or ill—of market forces both inside and outside the continent. As nation states decline in influence and power, and corporations, private patrons and foundations increasingly determine the kinds of cultural production that will be supported, how is African art being reinterpreted and by whom? Are artists and scholars able to successfully articulate their own intellectual and cultural values in this climate? Is there anything we can do to address the situation? WEDNESDAY, MARCH 23, 2O11, MUSEUM PROGRAM All Museum Program panels are in the Lenart Auditorium, Fowler Museum at UCLA Welcoming Remarks (8:30). Jean Borgatti, Steven Nelson, and Marla C. Berns PANEL I (8:45–10:45) Contemporary Art Sans Frontières. Chairs: Barbara Thompson, Stanford University, and Gemma Rodrigues, Fowler Museum at UCLA Contemporary African art is a phenomenon that transcends and complicates traditional curatorial categories and disciplinary boundaries. These overlaps have at times excluded contemporary African art from exhibitions and collections and, at other times, transformed its research and display into a contested terrain. At a moment when many museums with so‐called ethnographic collections are expanding their chronological reach by teasing out connections between traditional and contemporary artistic production, many museums of Euro‐American contemporary art are extending their geographic reach by globalizing their curatorial vision. -

36TH CAIRO INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL PROGRAMME November (9-18)

36TH CAIRO INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL PROGRAMME November (9-18) • No children are allowed. • Unified prices for all tickets: 20 EGP. • 50% discount for students of universities, technical institutes, and members of artistic syndicates, film associations and writers union. • Booking will open on Saturday, November 8, 2014 from 9am- 10pm. • Doors open 15 minutes prior to screenings • Doors close by the start of the screenings • No mobiles or cameras are allowed inside the screening halls. 1 VENUES OF THE FESTIVAL Main Hall – Cairo Opera House 1000 seats - International Competition - Special Presentations - Festival of Festivals (Badges – Tickets) Small Hall – Cairo Opera House 340 seats - Prospects of Arab Cinema (Badges – Tickets) - Films on Films (Badges) El Hanager Theatre - El Hanager Arts Center 230 seats - Special Presentations - Festival of Festivals (Badges – Tickets) El El Hanager Cinema - El Hanager Arts Center 120 seats - International Cinema of Tomorrow - Short films Competition - Student Films Competition - Short Film classics - Special Presentations - Festival of festivals (Badges) Creativity Cinema - Artistic Creativity Center 200 seats - International Critic’s Week - Feature Film Classics (Badges) El Hadara 1 75 seats - The Greek Cinema guest of honor (Badges) 2 El Hadara 2 75 seats - Reruns of the Main Hall Screenings El Hanager Foyer- El Hanager Arts Center - Gallery of Cinematic Prints Exhibition Hall- El Hanager Arts Center - Exhibition of the 100th birth anniversary of Barakat El- Bab Gallery- Museum of Modern Art - -

Redirected from Films Considered the Greatest Ever) Page Semi-Protected This List Needs Additional Citations for Verification

List of films considered the best From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia (Redirected from Films considered the greatest ever) Page semi-protected This list needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be chall enged and removed. (November 2008) While there is no general agreement upon the greatest film, many publications an d organizations have tried to determine the films considered the best. Each film listed here has been mentioned in a notable survey, whether a popular poll, or a poll among film reviewers. Many of these sources focus on American films or we re polls of English-speaking film-goers, but those considered the greatest withi n their respective countries are also included here. Many films are widely consi dered among the best ever made, whether they appear at number one on each list o r not. For example, many believe that Orson Welles' Citizen Kane is the best mov ie ever made, and it appears as #1 on AFI's Best Movies list, whereas The Shawsh ank Redemption is #1 on the IMDB Top 250, whilst Star Wars Episode V: The Empire Strikes Back is #1 on the Empire magazine's Top 301 List. None of the surveys that produced these citations should be viewed as a scientif ic measure of the film-watching world. Each may suffer the effects of vote stack ing or skewed demographics. Internet-based surveys have a self-selected audience of unknown participants. The methodology of some surveys may be questionable. S ometimes (as in the case of the American Film Institute) voters were asked to se lect films from a limited list of entries. -

List of Films Considered the Best

Create account Log in Article Talk Read View source View history Search List of films considered the best From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Main page This list needs additional citations for verification. Please Contents help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Featured content Current events Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (November Random article 2008) Donate to Wikipedia Wikimedia Shop While there is no general agreement upon the greatest film, many publications and organizations have tried to determine the films considered the best. Each film listed here has been mentioned Interaction in a notable survey, whether a popular poll, or a poll among film reviewers. Many of these sources Help About Wikipedia focus on American films or were polls of English-speaking film-goers, but those considered the Community portal greatest within their respective countries are also included here. Many films are widely considered Recent changes among the best ever made, whether they appear at number one on each list or not. For example, Contact page many believe that Orson Welles' Citizen Kane is the best movie ever made, and it appears as #1 Tools on AFI's Best Movies list, whereas The Shawshank Redemption is #1 on the IMDB Top 250, whilst What links here Star Wars Episode V: The Empire Strikes Back is #1 on the Empire magazine's Top 301 List. Related changes None of the surveys that produced these citations should be viewed as a scientific measure of the Upload file Special pages film-watching world. Each may suffer the effects of vote stacking or skewed demographics. -

Heroine: Female Agency in Joseph Ga㯠Ramaka's Karmen Geã¯

The "Monumental" Heroine: Female Agency in Joseph Gaï Ramaka's Karmen Geï Anjali Prabhu Cinema Journal, Volume 51, Number 4, Summer 2012, pp. 66-86 (Article) Published by University of Texas Press DOI: 10.1353/cj.2012.0088 For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/cj/summary/v051/51.4.prabhu.html Access Provided by Wellesley College Library at 11/10/12 7:18PM GMT The “Monumental” Heroine: Female Agency in Joseph Gaï Ramaka’s Karmen Geï by ANJALI PRABHU Abstract: Karmen Geï presents itself as a feminist African fi lm with a scandalously revolu- tionary central character. These aspects of the fi lm are reconsidered by focusing attention on the totality of its form, and by studying the politics of monumentalizing the heroine. he Senegalese fi lmmaker Joseph Gaï Ramaka’s chosen mode for representing his heroine in the fi lm Karmen Geï (2001) is that of the “monumental.” This has several consequences for the heroine’s possibilities within the diegesis. For example, the entire mise-en-scène makes the monumental heroine imperme- able to interpretation and resistant to critical discourses. This invites further evalua- Ttion of the fi lm’s political meanings, which have been much touted by critics. Critics and the fi lmmaker himself tend to agree on the fi lm’s political valence, primarily because of its unconventional, revolutionary heroine, and particularly because the fi lm is identifi ed as specifi cally African. My argument is twofold. First, I argue that Karmen Geï proposes what I am calling a monumental (and therefore an impossible) version of female identity and therefore also eschews many moments of plausible feminine agency. -

Cine-Ethiopia: the History and Politics of Film in the Horn of Africa Published by Michigan University Press DOI: 10.14321/J.Ctv1fxmf1

This is the version of the chapter accepted for publication in Cine-Ethiopia: The History and Politics of Film in the Horn of Africa published by Michigan University Press DOI: 10.14321/j.ctv1fxmf1 Accepted version downloaded from SOAS Research Online: http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/32029 CINE-ETHIOPIA THE HISTORY AND POLITICS OF FILM IN THE HORN OF AFRICA Edited by Michael W. Thomas, Alessandro Jedlowski & Aboneh Ashagrie Table of contents INTRODUCTION Introducing the Context and Specificities of Film History in the Horn of Africa, Alessandro Jedlowski, Michael W. Thomas & Aboneh Ashagrie CHAPTER 1 From የሰይጣን ቤት (Yeseytan Bet – “Devil’s House”) to 7D: Mapping Cinema’s Multidimensional Manifestations in Ethiopia from its Inception to Contemporary Developments, Michael W. Thomas CHAPTER 2 Fascist Imperial Cinema: An Account of Imaginary Places, Giuseppe Fidotta CHAPTER 3 The Revolution has been Televised: Fact, Fiction and Spectacle in the 1970s and 80s, Kate Cowcher CHAPTER 4 “The dead speaking to the living”: Religio-cultural Symbolisms in the Amharic Films of Haile Gerima, Tekletsadik Belachew CHAPTER 5 Whether to Laugh or to Cry? Explorations of Genre in Amharic Fiction Feature Films, Michael W. Thomas 2 CHAPTER 6 Women’s Participation in Ethiopian Cinema, Eyerusalem Kassahun CHAPTER 7 The New Frontiers of Ethiopian Television Industry: TV Serials and Sitcoms, Bitania Taddesse CHAPTER 8 Migration in Ethiopian Films, at Home and Abroad, Alessandro Jedlowski CHAPTER 9 A Wide People with a Small Screen: Oromo Cinema at Home and in Diaspora, Teferi Nigussie Tafa and Steven W. Thomas CHAPTER 10 Eritrean Films between Forced Migration and Desire of Elsewhere, Osvaldo Costantini and Aurora Massa CHAPTER 11 Somali Cinema: A Brief History between Italian Colonization, Diaspora and the New Idea of Nation, Daniele Comberiati INTERVIEWS Debebe Eshetu (actor and director), interviewed by Aboneh Ashagrie Behailu Wassie (scriptwriter and director), interviewed by Michael W. -

'Man on Wire', 'Searching for Sugar Man

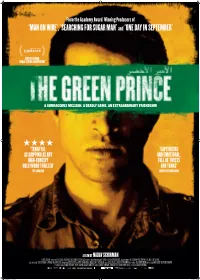

From the Academy Award® Winning Producers of ‘MAN ON WIRE’, ‘SEARCHING FOR SUGAR MAN’ and ‘ONE DAY IN SEPTEMBER’ AUDIENCE AWARD: WORLD CINEMA DOCUMENTARY A COURAGEOUS MISSION. A DEADLY GAME. AN EXTRAORDINARY FRIENDSHIP. ★★★★ ‘TERRIFFIC. ‘CAPTIVATING AS GRIPPING AS ANY AND EMOTIONAL. HIGH-CONCEPT FULL OF TWISTS HOLLYWOOD THRILLER’ AND TURNS’ THE GUARDIAN SCREEN INTERNATIONAL A FILM BY NADAV SCHIRMAN GLOBAL SCREEN PRESENTS AN A-LIST FILMS PASSION PICTURES AND RED BOX FILMS PRODUCTION IN CO-PRODUCTION WITH TELEPOOL AND URZAD PRODUCTIONS IN ASSOCIATION WITH THE DOCUMENTARY COMPANY YES DOCU SKY ATLANTIC BASED ON THE BOOK ‘SON OF HAMAS’ BY MOSAB HASSAN YOUSEF ORIGINAL MUSIC MAX RICHTER DOP HANS FROMM (BVK) GIORA BEJACH RAZ DAGAN EDITORS JOELLE ALEXIS SANJEEV HATHIRAMANI LINE PRODUCER RALF ZIMMERMANN CO-PRODUCERS OMRI UZRAD BRITTA MEYERMANN EXECUTIVE PRODUCERS THOMAS WEYMAR SHERYL CROWN MAGGIE MONTEITH PRODUCERS NADAV SCHIRMAN JOHN BATTSEK SIMON CHINN WRITTEN & DIRECTED BY NADAV SCHIRMAN greenprince_poster_a1_artwork.indd 1 27/01/2014 16:21 A feature documentary from the makers of SEARCHING FOR SUGARMAN, MAN ON WIRE, ONE DAY IN SEPTEMBER and THE CHAMPAGNE SPY A-List Films, Passion Pictures and Red Box Films present THE GREEN PRINCE Written & Directed by Nadav Schirman Produced by Nadav Schirman, John Battsek, Simon Chinn Running Time: 95 mins Press Contact North American Sales World Sales Acme PR Submarine Entertainment Global Screen GmbH Nancy Willen Josh Braun [email protected] 310 963 3433 917 687 3111 +49 89 24412950 [email protected] [email protected] www.globalscreen.de AWARDS & PRESS CLIPPINGS WINNER Audience Award Best World Documentary Sundance International Film Festival 2014 "Terrific.. -

2018 Community Cinema Conference & Film Society of the Year Awards Yourself on Screen

2018 Community Cinema Conference & Film Society of the Year Awards 7 — 9 September 2018 The Void (Sheffield Hallam University) and Showroom Workstation, Sheffield Yourself on Screen with the support of the BFI, awarding funds from The National Lottery What’s on Friday evening: Join film lecturer Dr. Emmie McFadden in The Void (part of Sheffield Hallam University) at 6.00pm for a fresh look at the classic Jimmy Stewart film Harvey – accompanied by a masterclass discussing depictions of mental health in film. Join us at Fusion Organic Café afterwards for excellent drinks, canapés and catching up. Our Friday night event is generously supported by our friends at WRS Insurance. Saturday daytime: The weekend begins in earnest with welcomes and introductions from the Cinema For All team. For our keynote session this year we are absolutely delighted to welcome Dr. Anandi Ramamurthy, Reader in Post- Colonial Cultures and Senior Lecturer in Media at Sheffield Hallam University, who will be joining us to talk about Palestinian Cinema. We are also incredibly excited to premiere Vote 100: Born a Rebel, a short film Cinema For All has made in collaboration with the Yorkshire Film Archive, the North West Film Archive and the North East Film Archive, and supported by the Women’s Vote Centenary Grant Scheme. The film is a celebration of women in civic life since the start of women’s suffrage in the UK, told through archive footage of women across the North of England. Following the morning session, delegates can choose between panels and workshops (including a very exciting Danny Leigh Film Discovery Masterclass) in the Creative Lounge, and a selection of fantastic films in Cinema 3. -

Exploring Trauma Through Fantasy

IN-BETWEEN WORLDS: EXPLORING TRAUMA THROUGH FANTASY Amber Leigh Francine Shields A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2018 Full metadata for this thesis is available in St Andrews Research Repository at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this thesis: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/16004 This item is protected by original copyright This item is licensed under a Creative Commons Licence https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ 4 Abstract While fantasy as a genre is often dismissed as frivolous and inappropriate, it is highly relevant in representing and working through trauma. The fantasy genre presents spectators with images of the unsettled and unresolved, taking them on a journey through a world in which the familiar is rendered unfamiliar. It positions itself as an in-between, while the consequential disturbance of recognized world orders lends this genre to relating stories of trauma themselves characterized by hauntings, disputed memories, and irresolution. Through an examination of films from around the world and their depictions of individual and collective traumas through the fantastic, this thesis outlines how fantasy succeeds in representing and challenging histories of violence, silence, and irresolution. Further, it also examines how the genre itself is transformed in relating stories that are not yet resolved. While analysing the modes in which the fantasy genre mediates and intercedes trauma narratives, this research contributes to a wider recognition of an understudied and underestimated genre, as well as to discourses on how trauma is narrated and negotiated. -

Paradise Now and Route 181. by Richard Porton

Roads to Somewhere: Paradise Now and Route 181. By Richa...http://www.cinema-scope.com/cs24/fea_porton_paradise.htm Search Roads to Somewhere: Articles in this Section Roads to Somewhere: Paradise Now and Route 181 Paradise Now and Route 181 by Richard Porton By Richard Porton and in the magazine... In the midst of some melancholy ruminations in Edward Said: The Last Waving Good-bye to Toronto: Don Owen’s Notes for Interview (2004), the late literary critic and political commentator remarks that a Film About Donna & Gail by Steve Gravestock the “useless” strategy of suicide bombing, embraced by some despairing Deadpan in Nulltown: On the Trail of Follow Me Palestinians since the advent of the second intifada, mirrors the useless and Quietly by B. Kite and Bill Krohn ineffectual policies of the Israeli state. Said’s explication is much more lucid and straightforward than many of the speculations concerning suicide missions that have recently appeared in the popular press. Far too many commentators appeal to vulgar assumptions concerning Islamic conceptions of Jihad, or what the French political scientist Olivier Roy rightly terms “the clichéd references to the seventy-two houris, or perpetual virgins, who are expecting the martyr.” Roy points out, in the midst of potted explanations of suicide attacks, many mainstream pundits invoke hoary notions of “Koranic Martyrdom” instead of nationalist and ethnic motivations. Yet Roy’s own attempt to explain these missions by appealing to a “Western tradition of individual and pessimistic revolt” seems equally myopic in its failure to address concrete political realities. His new clichés summing up “globalized Islam” have proved, perhaps unsurprisingly, appealing to conservative commentators eager to blame Western radicalism, instead of Islam, for the rash of suicide attacks—e.g. -

Understanding the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict

Understanding the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict Global Classroom Workshops made possible by: THE Photo Courtesy of Bill Taylor NORCLIFFE FOUNDATION A Resource Packet for Educators Compiled by Kristin Jensen, Jillian Foote, and Tese Wintz Neighbor And World May 12, 2009 Affairs Council Members HOW TO USE THIS RESOURCE GUIDE Please note: many descriptions were excerpted directly from the websites. Packet published: 5/11/2009; Websites checked: 5/11/2009 Recommended Resources Links that include… Lesson Plans & Charts & Graphs Teacher Resources Audio Video Photos & Slideshows Maps TABLE OF CONTENTS MAPS 1 FACT SHEET 3 TIMELINES OF THE CONFLICT 4 GENERAL RESOURCES ON THE ISRAELI-PALESTINIAN CONFLICT 5 TOPICS OF INTEREST 7 CURRENT ARTICLES/EDITORIALS ON THE ISRAELI-PALESTINIAN CONFLICT 8 (Focus on International Policy and Peace-Making) THE CRISIS IN GAZA 9 RIPPED FROM THE HEADLINES: WEEK OF MAY 4TH 10 RELATED REGIONAL ISSUES 11 PROPOSED SOLUTIONS 13 ONE-STATE SOLUTION 14 TWO-STATE SOLUTION 14 THE OVERLAPPING CONUNDRUM – THE SETTLEMENTS 15 CONFLICT RESOLUTION TEACHER RESOURCES 15 MEDIA LITERACY 17 NEWS SOURCES FROM THE MIDEAST 18 NGOS INVOLVED IN ISRAELI-PALESTINIAN RELATIONS 20 LOCAL ORGANIZATIONS & RESOURCES 22 DOCUMENTARIES & FILMS 24 BOOKS 29 MAPS http://johomaps.com/as/mideast.html & www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/is.html Other excellent sources for maps: From the Jewish Virtual Library - http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/History/maptoc.html Foundation for Middle East Peace - http://www.fmep.org/maps/ -

Toolkit: the Story of African Film Author: Lindiwe Dovey Toolkit: the Story of African Film 2 by Lindiwe Dovey

Toolkit: The Story of African Film Author: Lindiwe Dovey Toolkit: The Story of African Film 2 By Lindiwe Dovey Still from Pumzi (dir. Wanuri Kahiu, 2009), courtesy of director Toolkit: The Story of African Film 3 By Lindiwe Dovey Toolkit 1: The Story of African Film This Toolkit is a shortened version of an African film course syllabus by Lindiwe Dovey which she is sharing in the hopes that it can support others in teaching African film and/or better integrating African film into more general film and screen studies courses. The Story of African Film: Narrative Screen Media in sub-Saharan Africa A course developed by Professor Lindiwe Dovey Background to the Course I developed this course when I first arrived as a Lecturer in African Film at SOAS University of London in September 2007, and it has been taught every year at SOAS since then (by guest lecturers when I have been on sabbatical). Because of my passion for African filmmaking, it has been my favourite course to teach, and I have learned so much from the many people who have taken and contributed to it. I have been shocked over the years to hear from people taking the course (especially coming in to the UK from the US) that they could not find anything like it elsewhere; there are hundreds of film courses taught around the world, but so few give African film the deep attention it deserves. In a global context of neoliberal capitalism and the corporatisation of higher education I am concerned about what is going to happen to already-marginalised academic subjects like African film.