Paradise Now and Route 181. by Richard Porton

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

36TH CAIRO INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL PROGRAMME November (9-18)

36TH CAIRO INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL PROGRAMME November (9-18) • No children are allowed. • Unified prices for all tickets: 20 EGP. • 50% discount for students of universities, technical institutes, and members of artistic syndicates, film associations and writers union. • Booking will open on Saturday, November 8, 2014 from 9am- 10pm. • Doors open 15 minutes prior to screenings • Doors close by the start of the screenings • No mobiles or cameras are allowed inside the screening halls. 1 VENUES OF THE FESTIVAL Main Hall – Cairo Opera House 1000 seats - International Competition - Special Presentations - Festival of Festivals (Badges – Tickets) Small Hall – Cairo Opera House 340 seats - Prospects of Arab Cinema (Badges – Tickets) - Films on Films (Badges) El Hanager Theatre - El Hanager Arts Center 230 seats - Special Presentations - Festival of Festivals (Badges – Tickets) El El Hanager Cinema - El Hanager Arts Center 120 seats - International Cinema of Tomorrow - Short films Competition - Student Films Competition - Short Film classics - Special Presentations - Festival of festivals (Badges) Creativity Cinema - Artistic Creativity Center 200 seats - International Critic’s Week - Feature Film Classics (Badges) El Hadara 1 75 seats - The Greek Cinema guest of honor (Badges) 2 El Hadara 2 75 seats - Reruns of the Main Hall Screenings El Hanager Foyer- El Hanager Arts Center - Gallery of Cinematic Prints Exhibition Hall- El Hanager Arts Center - Exhibition of the 100th birth anniversary of Barakat El- Bab Gallery- Museum of Modern Art - -

Redirected from Films Considered the Greatest Ever) Page Semi-Protected This List Needs Additional Citations for Verification

List of films considered the best From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia (Redirected from Films considered the greatest ever) Page semi-protected This list needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be chall enged and removed. (November 2008) While there is no general agreement upon the greatest film, many publications an d organizations have tried to determine the films considered the best. Each film listed here has been mentioned in a notable survey, whether a popular poll, or a poll among film reviewers. Many of these sources focus on American films or we re polls of English-speaking film-goers, but those considered the greatest withi n their respective countries are also included here. Many films are widely consi dered among the best ever made, whether they appear at number one on each list o r not. For example, many believe that Orson Welles' Citizen Kane is the best mov ie ever made, and it appears as #1 on AFI's Best Movies list, whereas The Shawsh ank Redemption is #1 on the IMDB Top 250, whilst Star Wars Episode V: The Empire Strikes Back is #1 on the Empire magazine's Top 301 List. None of the surveys that produced these citations should be viewed as a scientif ic measure of the film-watching world. Each may suffer the effects of vote stack ing or skewed demographics. Internet-based surveys have a self-selected audience of unknown participants. The methodology of some surveys may be questionable. S ometimes (as in the case of the American Film Institute) voters were asked to se lect films from a limited list of entries. -

List of Films Considered the Best

Create account Log in Article Talk Read View source View history Search List of films considered the best From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Main page This list needs additional citations for verification. Please Contents help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Featured content Current events Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (November Random article 2008) Donate to Wikipedia Wikimedia Shop While there is no general agreement upon the greatest film, many publications and organizations have tried to determine the films considered the best. Each film listed here has been mentioned Interaction in a notable survey, whether a popular poll, or a poll among film reviewers. Many of these sources Help About Wikipedia focus on American films or were polls of English-speaking film-goers, but those considered the Community portal greatest within their respective countries are also included here. Many films are widely considered Recent changes among the best ever made, whether they appear at number one on each list or not. For example, Contact page many believe that Orson Welles' Citizen Kane is the best movie ever made, and it appears as #1 Tools on AFI's Best Movies list, whereas The Shawshank Redemption is #1 on the IMDB Top 250, whilst What links here Star Wars Episode V: The Empire Strikes Back is #1 on the Empire magazine's Top 301 List. Related changes None of the surveys that produced these citations should be viewed as a scientific measure of the Upload file Special pages film-watching world. Each may suffer the effects of vote stacking or skewed demographics. -

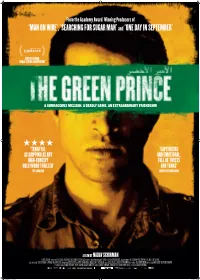

'Man on Wire', 'Searching for Sugar Man

From the Academy Award® Winning Producers of ‘MAN ON WIRE’, ‘SEARCHING FOR SUGAR MAN’ and ‘ONE DAY IN SEPTEMBER’ AUDIENCE AWARD: WORLD CINEMA DOCUMENTARY A COURAGEOUS MISSION. A DEADLY GAME. AN EXTRAORDINARY FRIENDSHIP. ★★★★ ‘TERRIFFIC. ‘CAPTIVATING AS GRIPPING AS ANY AND EMOTIONAL. HIGH-CONCEPT FULL OF TWISTS HOLLYWOOD THRILLER’ AND TURNS’ THE GUARDIAN SCREEN INTERNATIONAL A FILM BY NADAV SCHIRMAN GLOBAL SCREEN PRESENTS AN A-LIST FILMS PASSION PICTURES AND RED BOX FILMS PRODUCTION IN CO-PRODUCTION WITH TELEPOOL AND URZAD PRODUCTIONS IN ASSOCIATION WITH THE DOCUMENTARY COMPANY YES DOCU SKY ATLANTIC BASED ON THE BOOK ‘SON OF HAMAS’ BY MOSAB HASSAN YOUSEF ORIGINAL MUSIC MAX RICHTER DOP HANS FROMM (BVK) GIORA BEJACH RAZ DAGAN EDITORS JOELLE ALEXIS SANJEEV HATHIRAMANI LINE PRODUCER RALF ZIMMERMANN CO-PRODUCERS OMRI UZRAD BRITTA MEYERMANN EXECUTIVE PRODUCERS THOMAS WEYMAR SHERYL CROWN MAGGIE MONTEITH PRODUCERS NADAV SCHIRMAN JOHN BATTSEK SIMON CHINN WRITTEN & DIRECTED BY NADAV SCHIRMAN greenprince_poster_a1_artwork.indd 1 27/01/2014 16:21 A feature documentary from the makers of SEARCHING FOR SUGARMAN, MAN ON WIRE, ONE DAY IN SEPTEMBER and THE CHAMPAGNE SPY A-List Films, Passion Pictures and Red Box Films present THE GREEN PRINCE Written & Directed by Nadav Schirman Produced by Nadav Schirman, John Battsek, Simon Chinn Running Time: 95 mins Press Contact North American Sales World Sales Acme PR Submarine Entertainment Global Screen GmbH Nancy Willen Josh Braun [email protected] 310 963 3433 917 687 3111 +49 89 24412950 [email protected] [email protected] www.globalscreen.de AWARDS & PRESS CLIPPINGS WINNER Audience Award Best World Documentary Sundance International Film Festival 2014 "Terrific.. -

2018 Community Cinema Conference & Film Society of the Year Awards Yourself on Screen

2018 Community Cinema Conference & Film Society of the Year Awards 7 — 9 September 2018 The Void (Sheffield Hallam University) and Showroom Workstation, Sheffield Yourself on Screen with the support of the BFI, awarding funds from The National Lottery What’s on Friday evening: Join film lecturer Dr. Emmie McFadden in The Void (part of Sheffield Hallam University) at 6.00pm for a fresh look at the classic Jimmy Stewart film Harvey – accompanied by a masterclass discussing depictions of mental health in film. Join us at Fusion Organic Café afterwards for excellent drinks, canapés and catching up. Our Friday night event is generously supported by our friends at WRS Insurance. Saturday daytime: The weekend begins in earnest with welcomes and introductions from the Cinema For All team. For our keynote session this year we are absolutely delighted to welcome Dr. Anandi Ramamurthy, Reader in Post- Colonial Cultures and Senior Lecturer in Media at Sheffield Hallam University, who will be joining us to talk about Palestinian Cinema. We are also incredibly excited to premiere Vote 100: Born a Rebel, a short film Cinema For All has made in collaboration with the Yorkshire Film Archive, the North West Film Archive and the North East Film Archive, and supported by the Women’s Vote Centenary Grant Scheme. The film is a celebration of women in civic life since the start of women’s suffrage in the UK, told through archive footage of women across the North of England. Following the morning session, delegates can choose between panels and workshops (including a very exciting Danny Leigh Film Discovery Masterclass) in the Creative Lounge, and a selection of fantastic films in Cinema 3. -

Exploring Trauma Through Fantasy

IN-BETWEEN WORLDS: EXPLORING TRAUMA THROUGH FANTASY Amber Leigh Francine Shields A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2018 Full metadata for this thesis is available in St Andrews Research Repository at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this thesis: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/16004 This item is protected by original copyright This item is licensed under a Creative Commons Licence https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ 4 Abstract While fantasy as a genre is often dismissed as frivolous and inappropriate, it is highly relevant in representing and working through trauma. The fantasy genre presents spectators with images of the unsettled and unresolved, taking them on a journey through a world in which the familiar is rendered unfamiliar. It positions itself as an in-between, while the consequential disturbance of recognized world orders lends this genre to relating stories of trauma themselves characterized by hauntings, disputed memories, and irresolution. Through an examination of films from around the world and their depictions of individual and collective traumas through the fantastic, this thesis outlines how fantasy succeeds in representing and challenging histories of violence, silence, and irresolution. Further, it also examines how the genre itself is transformed in relating stories that are not yet resolved. While analysing the modes in which the fantasy genre mediates and intercedes trauma narratives, this research contributes to a wider recognition of an understudied and underestimated genre, as well as to discourses on how trauma is narrated and negotiated. -

Understanding the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict

Understanding the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict Global Classroom Workshops made possible by: THE Photo Courtesy of Bill Taylor NORCLIFFE FOUNDATION A Resource Packet for Educators Compiled by Kristin Jensen, Jillian Foote, and Tese Wintz Neighbor And World May 12, 2009 Affairs Council Members HOW TO USE THIS RESOURCE GUIDE Please note: many descriptions were excerpted directly from the websites. Packet published: 5/11/2009; Websites checked: 5/11/2009 Recommended Resources Links that include… Lesson Plans & Charts & Graphs Teacher Resources Audio Video Photos & Slideshows Maps TABLE OF CONTENTS MAPS 1 FACT SHEET 3 TIMELINES OF THE CONFLICT 4 GENERAL RESOURCES ON THE ISRAELI-PALESTINIAN CONFLICT 5 TOPICS OF INTEREST 7 CURRENT ARTICLES/EDITORIALS ON THE ISRAELI-PALESTINIAN CONFLICT 8 (Focus on International Policy and Peace-Making) THE CRISIS IN GAZA 9 RIPPED FROM THE HEADLINES: WEEK OF MAY 4TH 10 RELATED REGIONAL ISSUES 11 PROPOSED SOLUTIONS 13 ONE-STATE SOLUTION 14 TWO-STATE SOLUTION 14 THE OVERLAPPING CONUNDRUM – THE SETTLEMENTS 15 CONFLICT RESOLUTION TEACHER RESOURCES 15 MEDIA LITERACY 17 NEWS SOURCES FROM THE MIDEAST 18 NGOS INVOLVED IN ISRAELI-PALESTINIAN RELATIONS 20 LOCAL ORGANIZATIONS & RESOURCES 22 DOCUMENTARIES & FILMS 24 BOOKS 29 MAPS http://johomaps.com/as/mideast.html & www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/is.html Other excellent sources for maps: From the Jewish Virtual Library - http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/History/maptoc.html Foundation for Middle East Peace - http://www.fmep.org/maps/ -

Modern Palestinian Filmmaking in a Global World Sarah Frances Hudson University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 5-2017 Modern Palestinian Filmmaking in a Global World Sarah Frances Hudson University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the Near and Middle Eastern Studies Commons, and the Visual Studies Commons Recommended Citation Hudson, Sarah Frances, "Modern Palestinian Filmmaking in a Global World" (2017). Theses and Dissertations. 1872. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/1872 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Modern Palestinian Filmmaking in a Global World A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature and Cultural Studies by Sarah Hudson Hendrix College Bachelor of Arts in English Literature, 2007 University of Arkansas Master of Arts in Comparative Literature and Cultural Studies, 2011 May 2017 University of Arkansas This thesis/dissertation is approved for recommendation to the Graduate Council: ____________________________________________ Dr. Mohja Kahf Dissertation Director ____________________________________________ Dr. Ted Swedenburg Committee Member ____________________________________________ Dr. Keith Booker Committee Member Abstract This dissertation employs a comprehensive approach to analyze the cinematic accent of feature length, fictional Palestinian cinema and offers concrete criteria to define the genre of Palestinian fictional film that go beyond traditional, nation-centered approaches to defining films. Employing Arjun Appardurai’s concepts of financescapes, technoscapes, mediascapes, ethnoscapes, and ideoscapes, I analyze the filmic accent of six Palestinian filmmakers: Michel Khleifi, Rashid Masharawi, Ali Nassar, Elia Suleiman, Hany Abu Assad, and Annemarie Jacir. -

Negotiating Dissidence the Pioneering Women of Arab Documentary

NEGOTIATING DISSIDENCE THE PIONEERING WOMEN OF ARAB DOCUMENTARY STEFANIE VAN DE PEER Negotiating Dissidence Negotiating Dissidence The Pioneering Women of Arab Documentary Stefanie Van de Peer For Richie McCaffery Edinburgh University Press is one of the leading university presses in the UK. We publish academic books and journals in our selected subject areas across the humanities and social sciences, combining cutting-edge scholarship with high editorial and production values to produce academic works of lasting importance. For more information visit our website: edinburghuniversitypress.com © Stefanie Van de Peer, 2017 Edinburgh University Press Ltd The Tun – Holyrood Road 12 (2f) Jackson’s Entry Edinburgh EH8 8PJ Typeset in Monotype Ehrhardt by Servis Filmsetting Ltd, Stockport, Cheshire, and printed and bound in Great Britain by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 0 7486 9606 2 (hardback) ISBN 978 0 7486 9607 9 (webready PDF) ISBN 978 1 4744 2338 0 (epub) The right of Stefanie Van de Peer to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 and the Copyright and Related Rights Regulations 2003 (SI No. 2498). Contents List of Figures vi Acknowledgements vii Introduction 1 1 Ateyyat El Abnoudy: Poetic Realism in Egyptian Documentaries 28 2 Jocelyne Saab: Artistic-Journalistic Documentaries in Lebanese Times of War 55 3 Selma Baccar: Non-fiction in Tunisia, the Land of Fictions 83 4 Assia Djebar: -

Palestinian Film Directory 2019 the Palestine Film Institute (PFI) Is the National Body in Charge of Funding, Preserving and Promoting the Cinema of Palestine

Palestinian Film Directory 2019 The Palestine Film Institute (PFI) is the national body in charge of funding, preserving and promoting the cinema of Palestine. It seeks to support film productions from and for Palestine, through providing develop- ment and consultancy, increasing accessibility to funding, and connecting film talents and experts. The PFI is rooted in the tradition of committed cinema and the history of using independent film practice as a tool for social change. Palestine Film Directory has been produced for the occasion of the Marche du Film, Festival du Cannes 2019 With the support of the Palestinian Ministry of Culture, Bertha Foundation and the French Consulate in Je- rusalem. Senior Project Manager: Rashid Abdelhamid Public Program Curator: Mohanad Yaqubi Catalog Editor: Rana Anani Research Assistant: Dima Sharif Copy Editor: Casey Asprooth Jackson Designer: Hamza Abu Ayyash [email protected] www.palestinefilminstitute.org 2 Forward The Palestine Film Institute is proud to present the 2nd edition of the Palestine Film Directory, which contains updated contact information for more than 80 companies, platforms and initiatives active in the Palestinian film scene. These contacts have been vetted and confirmed by the PFI and are available for collaboration. Gathering in detail the active components of Palestine’s cinema is not an easy task. An active directory has to recon with unique challenges, including the Diaspora character of the scene, the role of Arab and Interna- tional producers and initiatives that work on Palestine related content, and the political question of where the Palestinian production boundaries lie. In light of these challenges, this directory should not be considered exhaustive, but rather should serve as a first point of connection for interested producers and organizations to interact with Palestine’s story through the feature film format. -

Mobility and the Representation of African Dystopian Spaces in Film and Literature a Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of Th

Mobility and the Representation of African Dystopian Spaces in Film and Literature A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Fine Arts of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Abobo Kumbalonah August 2015 © 2015 Abobo Kumbalonah. All Rights Reserved. 2 This dissertation titled Mobility and the Representation of African Dystopian Spaces in Film and Literature by ABOBO KUMBALONAH has been approved for Interdisciplinary Arts and the College of Fine Arts by Charles Buchanan Associate Professor of Interdisciplinary Arts Margaret Kennedy-Dygas Dean, College of Fine Arts 3 ABSTRACT KUMBALONAH, ABOBO, Ph.D., August 2015, Interdisciplinary Arts Mobility and the Representation of African Dystopian Spaces in Film and Literature Director of Dissertation: Charles Buchanan This study investigates the use of mobility as a creative style used by writers and filmmakers to represent the deterioration in the socio-economic and political circumstances of post-independence Africa. It makes a scholarly contribution to the field of postcolonial studies by introducing mobility as a new method for understanding film and literature. Increasingly, scholars in the social sciences are finding it important to examine mobility and its relationship with power and powerlessness among groups of people. This dissertation expands on the current study by applying it to the arts. It demonstrates how filmmakers and writers use mobility as a creative style to address issues such as economic globalization, international migration, and underdevelopment. Another significant contribution of this dissertation is that it introduces a new perspective to the debate on African migration. The current trend is for migrants to be seen in the light of vulnerability and powerlessness. -

Cinema at the End of Empire: a Politics of Transition

cinema at the end of empire CINEMA AT duke university press * Durham and London * 2006 priya jaikumar THE END OF EMPIRE A Politics of Transition in Britain and India © 2006 Duke University Press * All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper Designed by Amy Ruth Buchanan Typeset in Quadraat by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data and permissions information appear on the last printed page of this book. For my parents malati and jaikumar * * As we look back at the cultural archive, we begin to reread it not univocally but contrapuntally, with a simultaneous awareness both of the metropolitan history that is narrated and of those other histories against which (and together with which) the dominating discourse acts. —Edward Said, Culture and Imperialism CONTENTS List of Illustrations xi Acknowledgments xiii Introduction 1 1. Film Policy and Film Aesthetics as Cultural Archives 13 part one * imperial governmentality 2. Acts of Transition: The British Cinematograph Films Acts of 1927 and 1938 41 3. Empire and Embarrassment: Colonial Forms of Knowledge about Cinema 65 part two * imperial redemption 4. Realism and Empire 107 5. Romance and Empire 135 6. Modernism and Empire 165 part three * colonial autonomy 7. Historical Romances and Modernist Myths in Indian Cinema 195 Notes 239 Bibliography 289 Index of Films 309 General Index 313 ILLUSTRATIONS 1. Reproduction of ‘‘Following the E.M.B.’s Lead,’’ The Bioscope Service Supplement (11 August 1927) 24 2. ‘‘Of cource [sic] it is unjust, but what can we do before the authority.’’ Intertitles from Ghulami nu Patan (Agarwal, 1931) 32 3.