Legally Recognised Undead’: Essence, Difference, and Assimilation in Daniel Waters’S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thematic Connections Between Western and Zombie Fiction

Hang 'Em High and Bury 'Em Deep: Thematic Connections between Western and Zombie Fiction MICHAEL NGUYEN Produced in Melissa Ringfield’s Spring 2012 ENC1102 Zombies first shambled onto the scene with the release of Night of the Living Dead, a low- budget Romero film about a group of people attempting to survive mysterious flesh-eating husks; from this archetypical work, Night ushered in an era of the zombie, which continues to expand into more mediums and works to this day. Romero's own Living Dead franchise saw a revival as recently as 2004, more than doubling its filmography by the release of 2009's Survival of the Dead. As a testament to the pervasiveness of the genre, Max Brooks' zombie preparedness satire The Zombie Survival Guide alone has spawned the graphic novel The Zombie Survival Guide: Recorded Attacks and the spinoff novel World War Z, the latter of which has led to a film adaptation. There have been numerous articles that capitalize on the popularity of zombies in order to use them as a nuanced metaphor; for example, the graduate thesis Zombies at Work: The Undead Face of Organizational Subjectivity used the post-colonial Haitian zombie mythos as the backdrop of its sociological analysis of the workplace. However, few, if any, have attempted to define the zombie-fiction genre in terms of its own conceptual prototype: the Western. While most would prefer to interpret zombie fiction from its horror/supernatural fiction roots, I believe that by viewing zombie fiction through the analytical lens of the Western, zombie works can be more holistically described, such that a series like The Walking Dead might not only be described as a “show about zombies,” but also as a show that is distinctly American dealing with distinctly American cultural artifacts. -

Media and Identity in Post-War American and Global Fictions of the Undead

"Born in Death": Media and Identity in Post-War American and Global Fictions of the Undead Jonathan Mark Wilkinson MA by Research University of York English January 2015 2 Abstract Existing scholarship has largely overlooked that the undead are, famously, ‘us’. They are beings born from our deaths. Accordingly, their existence complicates the limits and value of our own. In this dissertation, I therefore argue that fictions of the undead reflect on questions of identity, meditating on the ways in which identities are created, distorted or otherwise reformed by the media to which their most important texts draw insistent attention. Analysing landmark texts from Post-War American contexts, this dissertation expands its hypothesis through three case studies, reading the texts in each as their own exercise in ontological thought. In each case study, I show that fictions of the undead reflect on the interactions between media and identity. However, there is no repeating model through which the themes of media, identity and undeath are repeatedly engaged. Each text’s formulation of these interacting themes is distinct to the other’s, suggesting that the significance of the undead and their respective tradition is not in the resounding ontological ‘answers’ that they and their texts inspire, but the questions that their problematic existential state asks. 3 List of Contents Abstract ..................................................................................................................2 Author’s Declaration .................................................................................................4 -

Heroism of Robert Neville in I Am Legend Movie William

HEROISM OF ROBERT NEVILLE IN I AM LEGEND MOVIE WILLIAM NICO SAPTONO ABSTRACT I am Legend is a film that tells about a military scientist who struggles to save human extinction from zombie virus. The purpose of this paper is to show the nature of heroism which exist in the protagonist’s characters. The writer uses library research in collecting the data. This analysis is supported by intrinsic elements as cinematography. In analyzing the extrinsic elements, the author uses the theory of heroism. The result of this paper is that Neville shows heroism act such as being decisive, creative in finding solution, being a religious man, helping and fighting the enemy. Those are aspects which represent characteristics of heroism in Neville. Keyword: I am Legend, heroism, zombie 1. Introduction Film is an expression of art which delivers many kinds of messages and topics, such as heroism. Heroism is a passion with higher purposes and great skill to think what he/she will do, not just emotional moment. Heroism has been used since the era of Ralph Waldo Emerson in 1841. It is a social value that has been applied since cave paintings, spread in oral tradition and molded legends, folktales, and myths into poems, epics (Carlyle, 1891; Hook, 1943; Klapp, 1948). Literature also emphasizes the word heroism as to help without any compensation. One of the films which talks about heroism is the Francis Lawrence movie’s I am Legend. It describes about the condition in the world that was infected by virus. People who infected the virus will become a zombie. -

Facing the Sublime: the Zombie Figure, Climate Change, and the Crisis of Categorization

Facing the Sublime Facing the Sublime: The Zombie Figure, Climate Change, and the Crisis of Categorization Elaine Chong Abstract In the article, zombies are presented as the 21st century’s way to encounter the sublime, and as a way to rethink the rigid binaries in Western culture and our effects on climate change. By applying Edmund Burke’s treatise, A Philosophical Inquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful, the terror equated with witnessing something neither alive nor dead is capable of creating feelings of the sublime. The horror instilled by the zombie is because this figure defies categorization in the most basic way –it exists between life and death. The author uses Marjorie Garber’s work Vested Interests that explores a “third” category that questions typical gender binary. This crisis of categorization works similarly with the zombie figure because it too lies in the middle of a stable, unchallengeable binary –that of life and death. This binary becomes permeable in zombie fiction, throwing the reader into a psychological state capable of experiencing the sublime. Zombies have evolved in each retelling. However in each the brain is the vital organ necessary for a zombie’s survival, including Warm Bodies, World War Z, and I Am Legend. Through a close reading of I Am Legend, the author argues that the existence of the zombie narrative parallels how the Western world has treated the planet and contributed to climate change. Zombies are a destructive vision of humanity, and through the “third” space that zombie literature provides, society is able to encounter the environmental damage it is inflicting on the planet. -

{Dоwnlоаd/Rеаd PDF Bооk} I Am Legend Ebook Free Download

I AM LEGEND PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Richard Matheson | 320 pages | 15 Jan 2008 | Doherty (Tom) Associates,U.S. | 9780765357151 | English | New York, United States I am Legend PDF Book Error rating book. This goes directly against the book's idea of Neville having unknowingly become a villain. Still, it helps along the way as sharing your status and other updates at certain junctures throughout the game grants you additional gold, treasure, experience points, and new monsters. The novel's vampires are also cannibalistic, preying on their own kind when they cannot find a human to consume. As time progresses, Neville turns scientific and discovers some of the microbiological aspects of the plague, as well as how it spreads from host to host. There are some excellent reviews out there. The only safe haven from the Darkseekers is daylight, since they experience severe reactions to UV light. Other reviewers noticed also that the monsters are closer in behaviour to zombies than to classic vampires. I read it years ago and while I find the writing in places rates my recognition of it's quality In October , Warner Bros. A FL native, Michael is passionate about pop culture, and earned an AS degree in film production in You've heard the one about the two good ol' boys from Arkansas who used a. You can deviate from the path as you become more comfortable. Chicago Review Press. I Am Legend. So, wrong, in the long run, but it made reading this for the first time a very different experience than it would be for someone who was going into it cold. -

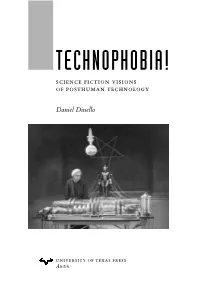

TECHNOPHOBIA! Science Fiction Visions of Posthuman Technology

TECHNOPHOBIA! science fiction visions of posthuman technology Daniel Dinello university of texas press Austin Frontispiece: Human under the domination of corporate science and autonomous technology (Metropolis, 1926. Courtesy Photofest). Copyright © 2005 by the University of Texas Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America First edition, 2005 Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to Permissions, University of Texas Press, P.O. Box 7819, Austin, TX 78713-7819. www.utexas.edu/utpress/about/bpermission.html The paper used in this book meets the minimum requirements of ansi/niso z39.48-1992 (r1997) (Permanence of Paper). library of congress cataloging-in-publication data Dinello, Daniel Technophobia! : science fiction visions of posthuman technology / by Daniel Dinello. — 1st ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 0-292-70954-4 (cl. : alk. paper) — isbn 0-292-70986-2 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Science fiction—History and criticism. 2. Technology in literature. I. Title. pn3433.6.d56 2005 809.3'876209356—dc22 2005019190 NINE Technology Is a Virus machine plague virus horror: technophobia and the return of repressed flesh Technophiliacs want to escape from the body—that mor- tal hunk of animated meat. But even while devising the mode of their disembodiment, a tiny terror gnaws inside them—virus fear. The smallest form of life, viruses are parasites that live and reproduce by penetrating and commandeering the cell machinery of their hosts, often killing them and moving on to others. ‘‘As the means become available for the technology- creating species to manipulate the genetic code that gave rise to it,’’ says techno-prophet Ray Kurzweil, ‘‘...newvirusescanemergethroughacci- dent and/or hostile intention with potentially mortal consequences.’’1 The techno-religious vision of immortality represses horrific images of mutilated bodies and corrupted flesh that haunt our collective nightmares in the science fiction subgenre of virus horror. -

Horror Rhetoric in Fiction and Film

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Theses Digitization Project John M. Pfau Library 2004 Causes of unease: Horror rhetoric in fiction and film Benjamin Kane Ethridge Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project Part of the Rhetoric Commons Recommended Citation Ethridge, Benjamin Kane, "Causes of unease: Horror rhetoric in fiction and film" (2004). Theses Digitization Project. 2766. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project/2766 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the John M. Pfau Library at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses Digitization Project by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CAUSES OF UNEASE: HORROR RHETORIC IN FICTION AND FILM A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in English Composition: English Literature by Benjamin Kane Ethridge December 2004 CAUSES OF UNEASE: HORROR RHETORIC IN FICTION AND FILM A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino by Benjamin Kane Ethridge December 2004 Approved by: Bruce Golden, Chair, English Dcfte © 2004 Benjamin Kane Ethridge ABSTRACT How do 'artists scare us? Horror Filmmakers and novelists alike can accomplish fear, revulsion, and disturbance in their respective audience. The rhetorical and stylistic strategies employed to evoke these feelings are unique to the gen're. Divulging these strategies will be the major focus of this thesis, yet there will also be discussion on the social and cultural background of the Horror genre. -

Revenant Landscapes in the Walking Dead

Revenant Landscapes in The Walking Dead Abstract This paper considers The Walking Dead comic (Kirkman, Moore and Adlard, Image 2003-present) and television series (AMC, 2010-present), arguing that although the two series rely on similar imagery they are distinct in their use of space. This contradicts established industry, audience and creator discourses surrounding this text and offers a counter-argument to the popular perspective that comics can be used as simple storyboards for their television adaptations. Firstly, geographies of the urban gothic and themes such as inversion and decay are used to interrogate paratextual claims of fidelity between the two texts. The paper compares key scenes and settings and goes beyond aesthetics to show that in both versions the functions of urban spaces are inverted (the highway, prison, farm, etc). It argues that the zombies’ decaying flesh echoes the disrepair of the landscape and the protagonists’ own bodily fragmentation through injury and violence is mirrored in the destruction of the places they encounter. These claims are then reconsidered using the space of the comics page, applying the work of Thierry Groensteen and critical theories of gothic narrative structure. This demonstrates that comics’ mono-sensory narratives allow depictions to be thematically linked with an emotive use of space to engage readers, and that this contributes to a gothic architecture of the page. The paper concludes that the critical discourse of fidelity that surrounds The Walking Dead is superficial and that each version’s spaces are medium-specific and distinct in their affect on the reader/viewer. Presenter biography: Dr Julia Round is a principal lecturer in the Faculty of Media and Communication at Bournemouth University, UK, and co-edits the academic journal Studies in Comics (Intellect). -

Female Characters in Psychological Horror

SLEZSKÁ UNIVERZITA V OPAVĚ Filozoficko-přírodověděcká fakulta v Opavě Veronika Hušková obor: Angličtina Female Characters in Psychological Horror Diplomová práce Vedoucí diplomové práce: Opava 2020 PhDr. Diana Adamová, Ph.D. Abstract This thesis deals with female characters in selected horror novels and their film adaptations from 1970 to 2019. Each chapter recounts the development of the horror genre in each decade and then highlights the selected novels in the decade’s context. The analytical part introduces the selected texts’ authors briefly and proceeds to analyze the female characters and their roles in the text, and how the filmmakers managed to translate the essence of these characters onto the big screen. The aim of this thesis is to provide a concise overview of the genre, categorize each female character and determine if and how did the portrayal of female characters change with time. Key words: horror, modern cinematography, American literature, British literature, Stephen King, Thomas Harris, Clive Barker, Jeff VanderMeer, female characters, Carrie, The Shining, Hellraiser, Misery, Silence of the Lambs, The Mist, It, Annihilation Abstrakt Tato práce se zabývá ženskými postavami ve vybraných hororových knihách a jejich filmových adaptacích od roku 1970 do roku 2019. Každá z kapitol nejdříve pojednává o vývoji hororového žánru v jednotlivých desetiletích a poté zasazuje vybraná díla do jejich kontextu. Analytická část nejprve krátce představuje autora knihy, dále se zaměřuje na analýzu ženských postav a jejich rolí v daném textu a jak se filmovým tvůrcům podařilo převést podstatu těchto postav na velké plátno. Cílem práce je poskytnutí stručného přehledu žánru, kategorizace jednotlivých ženských postav a určení toho, zda a jak se vyobrazení ženských postav vyvíjelo. -

Fragile Bodies in Stephenie Meyer's Twilight Series

Cultivating Perspectives: Fragile Bodies in Stephenie Meyer’s Twilight Series by Heather Simeney MacLeod A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Department of English and Film Studies University of Alberta © Heather Simeney MacLeod, 2014 ABSTRACT This dissertation project exposes the troubling engagement with classifications of materiality within text and bodies in Stephenie Meyer’s contemporary American vampire narrative, the Twilight Series (2005-2008). It does so by disclosing the troubling readings inherent in genre; revealing problematic representations in the gendered body of the protagonist, Bella Swan; exposing current cultural constructions of the adolescent female; demonstrating the nuclear structure of the family as inextricably connected to an iconic image of the trinity— man, woman, and child; and uncovering a chronicle of the body of the racialized “other.” That is to say, this project analyzes five persistent perspectives of the body—gendered, adolescent, transforming, reproducing, and embodying a “contact zone”—while relying on the methodologies of new feminist materialisms, posthumanism, postfeminism and vampire literary criticism. These conditions are characteristic of the “genre shift” in contemporary American vampire narrative in general, meaning that current vampire fiction tends to shift outside of the boundaries of its own classification, as in the case of Meyer’s material, which is read by a diverse readership outside of its Young Adult categorization. As such, this project closely examines the vampire exposed in Meyer’s remarkably popular text, as well as key texts published in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, such as Joss Whedon’s television series Buffy the Vampire Slayer (1997-2003), Alan Ball’s HBO series True Blood (2009-2014), Kathryn Bigelow’s Near Dark (1987) and Joel Schumacher’s The Lost Boys (1987). -

An Examination of Human Monstrosity in Fiction and Film of the United States

UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones 5-1-2012 Monsters in our Midst: An Examination of Human Monstrosity in Fiction and Film of the United States Michelle Kay Hansen University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations Part of the American Literature Commons, and the Film and Media Studies Commons Repository Citation Hansen, Michelle Kay, "Monsters in our Midst: An Examination of Human Monstrosity in Fiction and Film of the United States" (2012). UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones. 1572. http://dx.doi.org/10.34917/4332553 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MONSTERS IN OUR MIDST: AN EXAMINATION OF HUMAN MONSTROSITY IN FICTION AND FILM OF THE UNITED STATES By Michelle Kay Hansen Bachelor of Arts in Humanities Brigham Young -

Richard Matheson's I Am Legend

Adaptation Vol. 8, No. 1, pp. 130–144 doi:10.1093/adaptation/apv001 Richard Matheson’s I Am Legend: Colonization and Adaptation Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/adaptation/article/8/1/130/2447454 by Universidad Central user on 14 August 2020 NIcOLa BowrInG* Abstract This article examines questions of colonization and alterity alongside those of adapta- tion in Richard Matheson’s novel and three film adaptations of this. Matheson’s text, as a narrative about colonization, and as a hybrid text itself in terms of literary history, being both part adaptation and adaptatee, provides idea material for considering questions of adaptation and appropriation. This is explored through: narrative form and mis-en-scène; seeing and interpreting the other; hybridity; legend and fiction; and narrative history. Here adaptation is read in terms of adapting to a new environment and the process of alienation, and the adaption of texts or mythologies, which are read alongside one another to provide a reading of community, selfhood, adaptation, and history in the text. Keywords Matheson, vampires, alterity, adaptation, legend, myth, monstrosity. In a fictional Los Angeles in 1979, Robert Neville, the last human, looks out of his cell at the ‘new people of the earth’—a community of vampires—and feels keenly his own non-belonging, his new position as threatening outsider, monster: ‘anathema and black terror to be destroyed’ (160). Matheson’s 1954 novel, I Am Legend, has traced thus far Neville’s solitary existence in a post-plague world to the point of encounter with these vampire hybrids who have built up their new society, and his subsequent surrender to them.