Introduction to the Ratification of the Constitution in New York

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Minting America: Coinage and the Contestation of American Identity, 1775-1800

ABSTRACT MINTING AMERICA: COINAGE AND THE CONTESTATION OF AMERICAN IDENTITY, 1775-1800 by James Patrick Ambuske “Minting America” investigates the ideological and culture links between American identity and national coinage in the wake of the American Revolution. In the Confederation period and in the Early Republic, Americans contested the creation of a national mint to produce coins. The catastrophic failure of the paper money issued by the Continental Congress during the War for Independence inspired an ideological debate in which Americans considered the broader implications of a national coinage. More than a means to conduct commerce, many citizens of the new nation saw coins as tangible representations of sovereignty and as a mechanism to convey the principles of the Revolution to future generations. They contested the physical symbolism as well as the rhetorical iconology of these early national coins. Debating the stories that coinage told helped Americans in this period shape the contours of a national identity. MINTING AMERICA: COINAGE AND THE CONTESTATION OF AMERICAN IDENTITY, 1775-1800 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of History by James Patrick Ambuske Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2006 Advisor______________________ Andrew Cayton Reader_______________________ Carla Pestana Reader_______________________ Daniel Cobb Table of Contents Introduction: Coining Stories………………………………………....1 Chapter 1: “Ever to turn brown paper -

The Revolutionary Movement in New York, 1773–1777

University of Kentucky UKnowledge United States History History 1966 The Road to Independence: The Revolutionary Movement in New York, 1773–1777 Bernard Mason State University of New York at Binghamton Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Mason, Bernard, "The Road to Independence: The Revolutionary Movement in New York, 1773–1777" (1966). United States History. 66. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_united_states_history/66 The 'l(qpd to Independence This page intentionally left blank THE ROAD TO INDEPENDENCE The 'R!_,volutionary ~ovement in :J{£w rork, 1773-1777~ By BERNARD MASON University of Kentucky Press-Lexington 1966 Copyright © 1967 UNIVERSITY OF KENTUCKY PRESS) LEXINGTON FoR PERMISSION to quote material from the books noted below, the author is grateful to these publishers: Charles Scribner's Sons, for Father Knickerbocker Rebels by Thomas J. Wertenbaker. Copyright 1948 by Charles Scribner's Sons. The Bobbs-Merrill Company, Inc., for John Jay by Frank Monaghan. Copyright 1935 by the Bobbs-Merrill Com pany, Inc., renewed 1962 by Frank Monaghan. The Regents of the University of Wisconsin, for The History of Political Parties in the Province of New York J 17 60- 1776) by Carl L. Becker, published by the University of Wisconsin Press. Copyright 1909 by the Regents of the University of Wisconsin. -

De Witt Clinton and the Origin of the Spoils System in New York

73] Cornell University Library JK 731.M2 ... De Witt Clinton and the origin of th 3 1924 002 312 662 SlrUDEES IN HISTORY, ECONOMIOS AND PUBLIC LAW EDITED BY THE FACULTY OF POLITICAL SCIENCE OF COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY Volume XXVIII] [Number 1 De WITT CLINTON AUD THE ORIGIN OF THE SPOILS SYSTEM IN NEW YORK HOWARD LEE McBAIN, Ph.D., /Sometime Honorary Fellow in Constitutional Lam, Colwmhia Univeriity THE COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS THE MACMILLAN COMPANY, AGENTS London : P. S. King & Son 1907 THE LIBRARY OF THE NEW YORK STATE SCHOOL OF INDUSTRIAL AND LABOR RELATIONS AT CORNELL UNIVERSITY 1 DeWITT CLINTON AND THE ORIOIN OF THE SPOILS SYSTEM IN NEW YORK Cornell University Library The original of tiiis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924002312662 STUDIES IN HISTORY, ECONOMICS AND PUBLIC LAW EDITED BY THE FACULTY OF POLITICAL SCIENCE OF COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY Volume XXVIII] [Number 1 De WITT CLINTON AND THE ORIGIN OF THE SPOILS SYSTEM IN NEW YORK HOWARD LEE McBAIN, Ph.D., Sometime Honorary Fellow in Constitutional Law, Colvmhia University THE COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS THE MACMILLAN COMPANY, AGENTS London : P. S. King & Son 1907 Copyright, 1907, BY HOWARD LEE McBAIN 1 JK 1S) CONTENTS CHAPTER I EARLY PATRONAGE UNDER THE CONSTITUTION PAGE Introduction 11-15 Misrepresentations of DeWitt Clinton's policies 11-12 Sources for study of 12 Plan of present study of New York patronage 13-15 Relation of systems previous to 1801 13 Relation of national systems I3~i5 Washington's policy of patronage 15-25 His problems differ from those of his successors 16-17 His attitude toward anti-adoptionists 17-20 In general 17-18 In Rhode Island 18-20 His consideration of Revolutionary services 20-21 His general principles in making appointments 21-23 Later consideration of politics in cabinet appointments 23-24 His New York appointments—Theory of Hamiltonian influencejrefuted. -

Washington and Saratoga Counties in the War of 1812 on Its Northern

D. Reid Ross 5-8-15 WASHINGTON AND SARATOGA COUNTIES IN THE WAR OF 1812 ON ITS NORTHERN FRONTIER AND THE EIGHT REIDS AND ROSSES WHO FOUGHT IT 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Illustrations Maj. Gen. Jacob Brown 3 Map upstate New York locations 4 Map of Champlain Valley locations 4 Chapters 1. Initial Support 5 2. The Niagara Campaign 6 3. Action on Lake Champlain at Whitehall and Training Camps for the Green Troops 10 4. The Battle of Plattsburg 12 5. Significance of the Battle 15 6. The Fort Erie Sortie and a Summary of the Records of the Four Rosses and Four Reids 15 7. Bibliography 15 2 Maj. Gen. Jacob Brown as depicted3 in an engraving published in 1862 4 1 INITIAL SUPPORT Daniel T. Tompkins, New York’s governor since 1807, and Peter B. Porter, the U.S. Congressman, first elected in 1808 to represent western New York, were leading advocates of a war of conquest against the British over Canada. Tompkins was particularly interested in recruiting and training a state militia and opening and equipping state arsenals in preparation for such a war. Normally, militiamen were obligated only for three months of duty during the War of 1812, although if the President requested, the period could be extended to a maximum of six months. When the militia was called into service by the governor or his officers, it was paid by the state. When called by the President or an officer of the U.S. Army, it was paid by the U.S. Treasury. In 1808, the United States Congress took the first steps toward federalizing state militias by appropriating $200,000 – a hopelessly inadequate sum – to arm and train citizen soldiers needed to supplement the nation’s tiny standing army. -

George Washington Papers, Series 3, Subseries 3A, Varick Transcripts, Letterbook 6

George Washington Papers, Series 3, Subseries 3A, Varick Transcripts, Letterbook 6 To THE PRESIDENT OF CONGRESS Head Quarters, New Windsor, March 1, 1781. Sir: The inclosed memorial of Colo. Hazen was this day put into my hands. Many of the matters mentioned in it are better known to Congress than to myself. The whole are so fully stated, as to speak for themselves, and require only the determination of Congress. The case of the Canadian Officers and Soldiers I know to be peculiarly distressing and truly entitled to redress, if the means are to be obtained. The Regiment, not being appropriated to any State, must soon dwindle into nothing, unless some effectual mode can be devised for recruiting it. Colo. Hazens pretensions to promotion seems to me to have weight, but how far they ought to be admitted, the general principles which Congress mean to adopt for the regulation of this important point will best decide. In justice to Colo. Hazen, I must testify, that he has always appeared to me a sensible, 83 spirited and attentive Officer. I have the honor etc. To THE PRESIDENT OF CONGRESS Head Quarters, New Windsor, March 1, 1781. Sir: On opening the inclosed, I found it intended for 83. In the writing of Tench Tilghman. The letter was read in Congress on March 23 and referred to Artemas Ward, John Sullivan, and Isaac Motte. your Excellency, though addressed to me. I intend setting out in the morning for Newport to confer with the French General and Admiral upon the operations of the ensuing Campaign. -

A Short History of Poughkeepsie's Upper

A Short History of Poughkeepsie’s Upper Landing Written by Michael Diaz Chapter 1: Native Americans, the Dutch, and the English When Henry Hudson and his crew first sailed past what is now the City of Poughkeepsie in 1609, they sailed into a region that had been inhabited for centuries by a mixture of Algonquin-speaking peoples from the Mahican, Lenape, and Munsee cultures. The people living closest to the waterfall called “Pooghkepesingh” were Wappinger, part of the Lenape nation. The Wappinger likely had ample reason to settle near the Pooghkepesingh falls – the river and the small stream that ran to it from the falls provided good places to fish, and the surrounding hills offered both protection and ample opportunities to hunt. As the Dutch colony of New Netherland took shape along the banks of the Hudson River, the Dutch largely bypassed the river’s east bank. The Dutch preferred settling on the river’s mouth (now New York City), its northern navigable terminus (today’s Albany), and landings on the western bank of the Hudson (such as the modern city of Kingston). As such, Europeans did not show up in force near the Pooghkepesingh falls until the late 17th century. By that time, the Dutch had lost control of their colony to the English. It was a mix of these two groups that started building what is now the city of Poughkeepsie. On May 5, 1683, a Wappinger named Massany signed a deed giving control of the land around the Pooghkepesingh falls to two Dutch settlers, Pieter Lansingh and Jan Smeedes, who planned to build a mill on the small creek running from the falls. -

A General History of the Burr Family, 1902

historyAoftheBurrfamily general Todd BurrCharles A GENERAL HISTORY OF THE BURR FAMILY WITH A GENEALOGICAL RECORD FROM 1193 TO 1902 BY CHARLES BURR TODD AUTHOB OF "LIFE AND LETTERS OF JOBL BARLOW," " STORY OF THB CITY OF NEW YORK," "STORY OF WASHINGTON,'' ETC. "tyc mis deserves to be remembered by posterity, vebo treasures up and preserves tbe bistort of bis ancestors."— Edmund Burkb. FOURTH EDITION PRINTED FOR THE AUTHOR BY <f(jt Jtnuhtrboclur $«88 NEW YORK 1902 COPYRIGHT, 1878 BY CHARLES BURR TODD COPYRIGHT, 190a »Y CHARLES BURR TODD JUN 19 1941 89. / - CONTENTS Preface . ...... Preface to the Fourth Edition The Name . ...... Introduction ...... The Burres of England ..... The Author's Researches in England . PART I HISTORICAL AND BIOGRAPHICAL Jehue Burr ....... Jehue Burr, Jr. ...... Major John Burr ...... Judge Peter Burr ...... Col. John Burr ...... Col. Andrew Burr ...... Rev. Aaron Burr ...... Thaddeus Burr ...... Col. Aaron Burr ...... Theodosia Burr Alston ..... PART II GENEALOGY Fairfield Branch . ..... The Gould Family ...... Hartford Branch ...... Dorchester Branch ..... New Jersey Branch ..... Appendices ....... Index ........ iii PART I. HISTORICAL AND BIOGRAPHICAL PREFACE. HERE are people in our time who treat the inquiries of the genealogist with indifference, and even with contempt. His researches seem to them a waste of time and energy. Interest in ancestors, love of family and kindred, those subtle questions of race, origin, even of life itself, which they involve, are quite beyond their com prehension. They live only in the present, care nothing for the past and little for the future; for " he who cares not whence he cometh, cares not whither he goeth." When such persons are approached with questions of ancestry, they retire to their stronghold of apathy; and the querist learns, without diffi culty, that whether their ancestors were vile or illustrious, virtuous or vicious, or whether, indeed, they ever had any, is to them a matter of supreme indifference. -

History of Southold, L.I. : Its First Century

SOUTHOLD. 1 640- 1 740. B^^B HISTORY OF SOUTHOLD, L. I. ITS FIRST CENTURY. BY THE REV. EPHER WHITAKER, D. D., Pastor of the First Church of Southold, Councilor of the Long Island Historical Society, Corresponding Member of the New York Genealogical and Biographical Society, etc, SOUTHOLD: Printed for the Author. 1881. ^ t^^" COPYRIGHT BY EPHER WHITAKER. 1881, PRESS OF THE ORANGE CHRONICLE,, ORANGE, N. J, O 30 TO MR. THOMAS R. TROWBRIDGE AND MR. WILLIAM H. H. MOORE, WHO MAY SEVERALLY REPRESENT THE PLACES OF THEIR BIRTH, THE CENTRAL CITY AND THE REMOTEST TOWN OF ^ THE NEW HAVEN COLONY, AND WHOSE APPRECIATION AND GENEROSITY HAVE CHEERED THE PREPARATION OF THIS VOLUME, IT IS MOST • RESPECTFULLY AND GRATEFULLY DEDICATED BY THE AUTHOR. PREFACE. The acquisition of the greater part of the knowledge contained in this vohime has re- sulted Trom the duties and necessities of the Christian ministry in the pastoral care of the First' Church of Southold for the last thirty years. The preparation of the book for the press has been the rest and recreation of many a weary hour during most of this ministry. Various hindrances have resisted the accom- plishment of the undertaking, and caused a less orderly arrangement of the materials of the work, as well as a less vigorous and at- tra6tive style, than could be desired; but the belief is cherished, that the imperfections of the book, however clearly seen by the reader, and deeply felt by the writer, should not for- bid its publication. For it is highly desirable, that the early life and worth—the purpose. -

War, Murder, and a “Monster of a Man” in Revolutionary New England

THE ANXIOUS ATLANTIC: WAR, MURDER, AND A “MONSTER OF A MAN” IN REVOLUTIONARY NEW ENGLAND A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY by David W. Thomas December 2018 Examining Committee Members: Travis Glasson, Advisory Chair, Department of History Mónica Ricketts, Department of History Jessica Roney, Department of History David Waldstreicher, External Member, The Graduate Center, CUNY Richard Bell, External Member, University of Maryland ii © Copyright 2018 by David W. Thomas All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT On December 11, 1782 in Wethersfield, Connecticut, a fifty-two year old English immigrant named William Beadle murdered his wife and four children and took his own life. Beadle’s erstwhile friends were aghast. William was no drunk. He was not abusive, foul-tempered, or manifestly unstable. Since arriving in 1772, Beadle had been a respected merchant in Wethersfield good society. Newspapers, pamphlets, and sermons carried the story up and down the coast. Writers quoted from a packet of letters Beadle left at the scene. Those letters disclosed Beadle’s secret allegiance to deism and the fact that the War for Independence had ruined Beadle financially, in his mind because he had acted like a patriot not a profiteer. Authors were especially unnerved with Beadle’s mysterious past. In a widely published pamphlet, Stephen Mix Mitchell, Wethersfield luminary and Beadle’s one-time closest friend, sought answers in Beadle’s youth only to admit that in ten years he had learned almost nothing about the man print dubbed a “monster.” This macabre story of family murder, and the fretful writing that carried the tale up and down the coast, is the heart of my dissertation. -

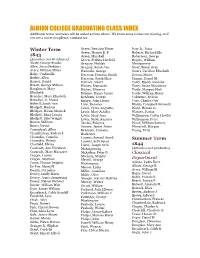

ALBION COLLEGE GRADUATING CLASS INDEX Additional Terms and Years Will Be Added As Time Allows

ALBION COLLEGE GRADUATING CLASS INDEX Additional terms and years will be added as time allows. We know some names are missing, so if you see a correction please, contact us. Winter Term Green, Denslow Elmer Pray Jr., Isaac Green, Harriet E. F. Roberts, Richard Ely 1843 Green, Marshall Robertson, George [Attendees not Graduates] Green, Perkins Hatfield Rogers, William Alcott, George Brooks Gregory, Huldah Montgomery Allen, Amos Stebbins Gregory, Sarah Ann Stout, Byron Gray Avery, William Miller Hannahs, George Stuart, Caroline Elizabeth Baley, Cinderella Harroun, Denison Smith Sutton, Moses Barker, Ellen Harroun, Sarah Eliza Timms, Daniel M. Barney, Daniel Herrick, Albert Torry, Ripley Alcander Basset, George Stillson Hickey, Manasseh Torry, Susan Woodbury Baughman, Mary Hickey, Minerva Tuttle, Marquis Hull Elizabeth Holmes, Henry James Tuttle, William Henry Benedict, Mary Elizabeth Ketchum, George Volentine, Nelson Benedict, Jr, Moses Knapp, John Henry Vose, Charles Otis Bidwell, Sarah Ann Lake, Dessoles Waldo, Campbell Griswold Blodgett, Hudson Lewis, Cyrus Augustus Ward, Heman G. Blodgett, Hiram Merrick Lewis, Mary Athalia Warner, Darius Blodgett, Mary Louisa Lewis, Mary Jane Williamson, Calvin Hawley Blodgett, Silas Wright Lewis, Sarah Augusta Williamson, Peter Brown, William Jacobs, Rebecca Wood, William Somers Burns, David Joomis, James Joline Woodruff, Morgan Carmichael, Allen Ketchum, Cornelia Young, Urial Chamberlain, Roderick Rochester Champlin, Cornelia Loomis, Samuel Sured Summer Term Champlin, Nelson Loomis, Seth Sured Chatfield, Elvina Lucas, Joseph Orin 1844 Coonradt, Ann Elizabeth Mahaigeosing [Attendees not graduates] Coonradt, Mary Margaret McArthur, Peter D. Classical Cragan, Louisa Mechem, Stanley Cragan, Matthew Merrill, George Department Crane, Horace Delphin Washington Adkins, Lydia Flora De Puy, Maria H. Messer, Lydia Allcott, George B. -

Verley Archer Papers

Verley Archer Collection 1960’s - 1980’s Collection Number: MSS 254 Size: 8.76 linear feet Special Collections and University Archives Jean and Alexander Heard Library Vanderbilt University Nashville, Tennessee © Vanderbilt University Special Collections and University Archives Verley Archer Collection Scope and Content Note The Verley Archer Collection consists of materials relating to the Vanderbilt Family Reunion held in conjunction with the Centennial Celebration of Vanderbilt University, March 16-17, 1973. Ms. Archer conducted extensive research into the genealogy of the Vanderbilt family and located descendants of Commodore Cornelius Vanderbilt living in 1973. Included in the Verley Archer Collection are research notes and materials, completed questionnaires from family members, correspondence, publicity materials, and published books, all relating to the Family Reunion and Centennial Celebration. The 21 boxes in this collection cover approximately 8.76 linear feet. The collection is arranged in 3 series: Subject Files (Series 1); Vanderbilt Centennial (series 2); and Verley Archer’s Research Materials (Series 3). The Subject Files, Series 1, are the most extensive part of this collection. They consist of letters, completed questionnaires, and biographical information on most of the over 500 members of the Vanderbilt family living in 1973, as well as some earlier family members. These are arranged alphabetically by last name. Married women descendants are cross-referenced by their maiden names. Series 2 consists of the form letter mailings sent to his Vanderbilt relatives by William H. Vanderbilt, III and their responses. Also included are publicity articles about the Vanderbilt Family Reunion and Vanderbilt University Centennial. There are lists of descendants attending the Reunion and of gifts to Vanderbilt University from the descendants. -

The Constitutional History of New York

The Constitutional History of New York Charles Z. Lincoln's five-volume The Constitutional History of New York from the Beginning of the Colonial Period to the Year 1905, Showing the Origin, Development, and Judicial Construction of the Constitution remains the authoritative history of the evolution of the State Constitution through the 19th century and the forces that shaped the principles it has embraced. The Historical Society of the Courts of the State of New York has excerpted a number of passages from this compilation which are of particular relevance to the history of the State Courts: • A profile of the author • The Colonial Judiciary • The New York Judiciary, 1777-1845 • The Judiciary Article Under the Third Constitution (1846) • The First Constitution, 1777 • Amendments to the First Constitution - The Convention of 1801 • Woman Suffrage • Woman Suffrage Addendum CHARLES Z. LINCOLN Charles Z. Lincoln was born August 5, 1848, at Grafton, Vermont. An orphan at eight years of age, he resided during his childhood years with various relatives. He was educated in public schools and at Chamberlain Institute, in Randolph, New York. Mr. Lincoln taught school in Cattaraugus and Chautauqua Counties until 1871, when he began the study of law with Joseph R. Jewell, at Little Valley, New York, and with Charles S. Cary, at Olean, New York. He was admitted to the bar in 1874 and thereafter engaged in private practice. He has been President and Attorney of [photograph and biographical Little Valley, a member of the Board of information courtesy of the Education, a State Senator and a Convention Manual of the Sixth New Delegate to the New York Constitutional York State Constitutional Convention Convention of 1894.