A Metaphorical Study on Chinese Neologisms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

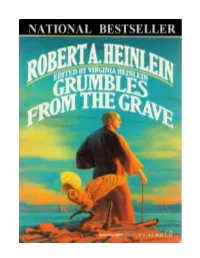

Grumbles from the Grave

GRUMBLES FROM THE GRAVE Robert A. Heinlein Edited by Virginia Heinlein A Del Rey Book BALLANTINE BOOKS • NEW YORK For Heinlein's Children A Del Rey Book Published by Ballantine Books Copyright © 1989 by the Robert A. and Virginia Heinlein Trust, UDT 20 June 1983 All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Ballantine Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Grateful acknowledgment is made to the following for permission to reprint the following material: Davis Publications, Inc. Excerpts from ten letters written by John W. Campbell as editor of Astounding Science Fiction. Copyright ® 1989 by Davis Publications, Inc. Putnam Publishing Group: Excerpt from the original manuscript of Podkayne of Mars by Robert A. Heinlein. Copyright ® 1963 by Robert A. Heinlein. Reprinted by permission of the Putnam Publishing Group. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 89-6859 ISBN 0-345-36941-6 Manufactured in the United States of America First Hardcover Edition: January 1990 First Mass Market Edition: December 1990 CONTENTS Foreword A Short Biography of Robert A. Heinlein by Virginia Heinlein CHAPTER I In the Beginning CHAPTER II Beginnings CHAPTER III The Slicks and the Scribner's Juveniles CHAPTER IV The Last of the Juveniles CHAPTER V The Best Laid Plans CHAPTER VI About Writing Methods and Cutting CHAPTER VII Building CHAPTER VIII Fan Mail and Other Time Wasters CHAPTER IX Miscellany CHAPTER X Sales and Rejections CHAPTER XI Adult Novels CHAPTER XII Travel CHAPTER XIII Potpourri CHAPTER XIV Stranger CHAPTER XV Echoes from Stranger AFTERWORD APPENDIX A Cuts in Red Planet APPENDIX B Postlude to Podkayne of Mars—Original Version APPENDIX C Heinlein Retrospective, October 6, 1988 Bibliography Index FOREWORD This book does not contain the polished prose one normally associates with the Heinlein stories and articles of later years. -

New Language – References

NEW LANGUAGE – REFERENCES I’m very grateful indeed to Dennis Davy for permission to reproduce here his 2006 bibliography and webliography of Lexical Innovation (the coining of new words and expressions). Dennis Davy is Head of the Language Department at MIP School of Management, Paris, and Lecturer at the Ecole Polytechnique. He can be contacted on [email protected] Lexical Innovation Bibliography Adams V (1973) An Introduction to Modern English Word Formation Longman : London Algeo J (ed) (1991) Fifty Years Among the New Words: A Dictionary of Neologisms (1941-1991) CUP: Cambridge Andreyev J (2005) Wondering about Words : D’où viennent les mots anglais ? Bréal : Rosny-sous-Bois Ayto J (1989) The Longman Register of New Words Longman: Harlow, Essex Ayto J (1990) The Longman Register of New Words (Volume Two 1990) Longman: Harlow, Essex Ayto J (2006) Movers and Shakers: A Chronology of Words that Shaped Our Age OUP: Oxford Ayto J (1999) 20 th Century Words: The Story of the New Words in English over the Last Hundred Years OUP: Oxford Ball RV (1990) “Lexical innovation in present-day French – le français branché” French Cultural Studies 1, pp 21-35 Barker-Main K (2006) Say What? New Words Around Town: The A-Z of Smart Talk Metro Publishing: London Barnhart CL, Steinmetz S & Barnhart RK (1973) A Dictionary of New English 1963-1972 Longman: London Barnhart CL, Steinmetz S & Barnhart RK (1980) The Second Barnhart Dictionary of New English Barnhart Books: New York Barnhart RK & Steinmetz S (1992) The Third Barnhart Dictionary of New -

Fake News Phenomenon a Corpus Linguistic Analysis of the Term Fake News

Johanna Tolonen The fake news phenomenon A Corpus Linguistic Analysis of the term fake news Faculty of Information and Communication Sciences Bachelor’s Thesis August 2019 Tolonen, Johanna: The fake news phenomenon: A Corpus Linguistic Analysis of the term fake news Kandidaatintutkielma, 22 sivua+liitteet Tampereen yliopisto Kielten kandidaattiohjelma, Englannin opintosuunta Elokuu 2019 Tämä tutkimus käsittelee fake news-termin nopeaa kansainvälistä leviämistä ja sitä, minkälaisten sanojen yhteydessä termi useimmiten esiintyy. Fake news on nopeasti saavuttanut maailmanlaajuisen ilmiön maineen viimeisen kuluneen kolmen vuoden aikana. Termin ilmiömäinen kansainvälinen leviäminen näkyy esimerkiksi siten, että fake news valittiin vuonna 2017 vuoden sanaksi. Tutkimuksen tavoitteena on selvittää News on the Web (NOW)- ja Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA)-korpuksia hyödyntäen, mitkä verbit ja adjektiivit esiintyvät useimmiten fake news-termin välittömässä läheisyydessä. Tutkimuksessa keskitytään tarkastelemaan termin esiintymistä lauseessa verbien ja adjektiivien jälkeen. Tutkimuksen tarkoituksena on vastata seuraaviin kysymyksiin: 1) Miten termin fake news käyttö on muuttunut elokuun 2016 ja joulukuun 2017 välisenä aikana? 2) Mitkä tekijät ovat vaikuttaneet mahdolliseen muutokseen? 3)Mitkä adjektiivit ja verbit esiintyvät useimmiten termin fake news kanssa? 4) Mitä korpuksiin pohjautuvat tutkimukset voivat paljastaa kielenkäytön muutoksista? Tutkimuksen aineistona toimi News on the Web (NOW) sekä Corpus of Contemporary American -

Neologisms of Popular Culture and Lifestyle in the Jakarta Post

NEOLOGISMS OF POPULAR CULTURE AND LIFESTYLE IN THE JAKARTA POST THESIS Submitted in the Board of Examiners In Partial Fulfillment of Requirement for Literature Degree at English Literature Department by TAKMILATUL FIKRIAH AI.150353 ADAB AND HUMANITIES FACULTY THE STATE ISLAMIC UNIVERSITY SULTHAN THAHA SAIFUDDIN JAMBI 2019 MOTTO The meaning “It is Allah who has created seven heavens and of the earth, the like of them. [His] command descends among them so you may know that Allah is over all things competent and that Allah has encompassed all things in knowledge.” (Q.S. At-Talaq:12)1 Artinya: “Allah-lah yang menciptakan tujuh langit dan seperti itu pula bumi. perintah Allah Berlaku padanya, agar kamu mengetahui bahwasanya Allah Maha Kuasa atas segala sesuatu, dan Sesungguhnya Allah ilmu-Nya benar-benar meliputi segala sesuatu”. 1The Noble Qur‟an. (2016). Qur‟an.com (Also known as The Noble Qur‟an. Al Quran. Holy Quran, Koran). Retrieved from https://www.quran.com Accessed on September, 27th 2019 at 3:25 am. DEDICATION . I thank to Allah SWT who has blessed and strength on me so I can accomplish this thesis. Shalawat and salam to Prophet Muhammad SAW who has brought human‟s life to a better life and to a beautiful world. Proudly, I dedicate this thesis to my beloved Mak (Padhliah) and Ayah (Bahrim) who always love and support me to keep live the life of my dream and my education. For to my beloved young brother Ridhal Qalbi and young sister Khairun Nisa always make me happy and missing, for my beloved Deh (Najad), alm. -

Neologisms in Online British-English Versus American-English Dictionaries

LEXICOGRAPHY IN GLOBAL CONTEXTS 545 Neologisms in Online British-English versus American-English Dictionaries Sharon Creese Coventry University E-mail: [email protected] Abstract A common source of publicity for modern-day dictionary publishers is the regular (usually quarterly) release of lists of neologisms that have recently been added to their online dictionaries.1 The publishing of updated versions of these sites every few months means it may no longer take years for new words to be included in a dictionary. However while different dictionaries may utilize neologisms in similar ways in order to improve brand awareness, the way in which these new words are presented and used in the dictionaries themselves can vary widely, including amongst those of differing varieties of English. This paper will describe differences in the approach and treatment of British-English neologisms in online editions of British-English dictionary OED (the Oxford English Dictionary) and American-English dictionary Merriam-Webster. In particular, the way in which each dictionary responds to potential new words will be discussed, as will the comprehensiveness of the resulting new entries and the differences found in the types of information each contains. Keywords: neologism, lexicography, dictionaries, dictionary components, British-English, American-Eng- lish, OED, Merriam-Webster 1 Introduction Thousands of new words enter online dictionaries every year; according to their own publicity material, some 3,200 entered the Oxford English Dictionary (OED, Third Edition) during the year to January 2018,2 while 1,100 entered Merriam-Webster3 in the 12 months to March 2018.4 Many of these novel words name or describe new items or concepts created through innovations in science and technology (Lehrer 2003: 371; Francl 2011: 417; Mitchell 2008: 33), and many others are coined by journalists or other professional writers, often in a bid to inject humor into a story, or simply as an expression of lan- guage play (Renouf 2007: 70). -

CLIPPING in ENGLISH SLANG NEOLOGISMS Dmytro Borys

© 2018 D. Borys Research article LEGE ARTIS Language yesterday, today, tomorrow Vol. III. No 1 2018 CLIPPING IN ENGLISH SLANG NEOLOGISMS Dmytro Borys Kyiv National Linguistic University, Kyiv, Ukraine Borys, D. (2018). Clipping in English slang neologisms. In Lege artis. Language yesterday, today, tomorrow. The journal of University of SS Cyril and Methodius in Trnava. Warsaw: De Gruyter Open, 2018, III (1), June 2018, p. 1-45. DOI: 10.2478/lart-2018-0001 ISSN 2453-8035 Abstract: The research is concerned with the phonotactic, morphotactic, graphic, logical, derivational, and syntactic features of clipped English slang neologisms coined in the early 21st century. The main preconceptions concerning clipping per se are revisited and critically rethought upon novel slang material. An innovative three-level taxonomy of clippings is outlined. The common and distinctive features of diverse types of clipping are identified and systemized. Key words: clipping, slang neologism, back-clipping, mid-clipping, fore-clipping, edge-clipping. 1. Introduction Redundancy ubiquitously permeates human life. According to Cherry, "redundancy is built into the structural forms of different languages in diverse ways" (1957: 18-19, 118). In linguistics, it accounts for adaptability as one of the driving factors of language longevity and sustainability. In lexicology, redundancy underlies the cognitive process of conceptualization (Eysenck & Keane 2000: 306-307); constitutes a prerequisite for secondary nomination and semantic shifting; contributes to assimilation of borrowings; nurtures the global trend in all-pervasive word structure simplification, affecting lexicon and beyond. In word formation, the type of redundancy involved is dimensional redundancy, which is defined as "the redundancy rate of information dimensions" (Hsia 1973: 8), as opposed to between-channel, distributional, sequential, process-memory, and semiotic redundancies (ibid., 8-9). -

Translation of Neologisms

European Journal of Research Development and Sustainability (EJRDS) Available Online at: https://www.scholarzest.com Vol. 2 No. 6, June 2021, ISSN: 2660-5570 TRANSLATION OF NEOLOGISMS Mamurova Mehrinoz Jamil Qizi, Master of Uzbekistan State University of World Languages [email protected] +998 94 322 82 44 Article history: Abstract: Received: April 28th 2021 This article discusses the study of the distortion of neologisms in the translation Accepted: May 17th 2021 process in all areas, including language. Published: June 12th 2021 Keywords: Neologisms, translate, words, types, Readership DEFINITION OF NEOLOGISM: Neologisms can be defined as newly coined lexical units or existing lexical units that acquire a new sense. In other words, Neologisms are new words, word-combinations or fixed phrases that appear in the language due to the development of social life, culture, science and engineering. New meanings of existing words are also accepted as neologisms. A problem of translation of new words ranks high on the list of challenges facing translators because such words are not readily found in ordinary dictionaries and even in the newest specialized dictionaries. Neologisms pass through three stages: . Creation . Trial . Establishment NEOLOGISMS AS A PROBLEM: Neologisms are a problem because of . New ideas and variations because of media . Excessive use of Slang . Each language acquires 3000 new words annually . Most people like neologisms, and so the media and commercial interests exploit this liking. DIFFERENT TYPES OF NEOLOGISM AND THEIR TRANSLATION: Old Words With New Sense: Sometimes existing words are used with new sense. Old words with new senses tend to be non-cultural and nontechnical. -

The Marketing Potential of Phono-Semantic Matching in China

One name, two parents: The marketing potential of Phono-Semantic Matching in China Sarah Fleming Chinese Institute University of Oxford Ghil‘ad Zuckermann Chair of Linguistics and Endangered Languages The University of Adelaide, Australia One name, two parents: The marketing potential of Phono-Semantic Matching in China Abstract: Phono-Semantic Matching (PSM) is a camouflaged borrowing in which a foreign lexical item is matched with a phonetically and semantically similar pre-existent native word. The neologism resulting from such source of lexical expansion preserves both the meaning and the approximate sound of the reproduced expression in the Source Language (SL) with the help of pre-existent Target Language (TL) elements. This paper analyses the marketing potential of PSM in contemporary China, arguing that PSM provides manipulation of the foreign term and thus controlled nativization of it. Keywords: lexical expansion, translation, Phono-Semantic Matching (PSM), Chinese. Introduction Phono-Semantic Matching (Zuckermann 1999: 331, 2003, 2005, 2009; henceforth PSM) is a camouflaged borrowing in which a foreign lexical item is matched with a phonetically and semantically similar pre-existent native word/root. The neologism resulting from such source of lexical expansion preserves both the meaning and the approximate sound of the reproduced expression in the Source Language (SL) with the help of pre- existent Target Language (TL) elements. (Neologism is used in its broader meaning, i.e. either an entirely new lexical item or a TL pre-existent word whose meaning has been altered, resulting in a new sense.) Such ‘lexical accommodations’ (Dimmendaal 2001: 363) are inter alia common in two key language groups: (1) languages using a phono-logographic script that does not allow mere phonetic adaptation, e.g. -

The Translatability of English Social Media Neologisms Into Arabic

An-Najah National University Faculty of Graduate Studies The Translatability of English Social Media Neologisms into Arabic By Rahma Abd Al-Rahman Naji Kmail Supervisor Dr. Ayman Nazzal This Thesis is Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Applied Linguistics and Translation, Faculty of Graduate Studies, An-Najah National University, Nablus, Palestine. 2016 II The Translatability of English Social Media Neologisms into Arabic By Rahma Abd Al-Rahman Naji Kmail This Thesis was defended successfully on 20/12/2016 and approved by: Defense Committee Members Signature Dr. Ayman Nazzal / Supervisor ………..……… Dr. Mahmoud Shreteh / External Examiner ………..……… Dr. Abdel Karim Daragmeh / Internal Examiner ………..……… III Dedication To the souls of Palestinian martyrs who sacrifice their lives for the sake of this land. To my father's soul, may his soul rest in peace. To everyone who encouraged me to go on and stead fast in the face of all the challenges and difficulties I encountered through this long, tiring journey. IV Acknowledgment I would like to thank my thesis supervisor Dr. Ayman Nazzal at An-Najah National University. His door was always open for me. He was there for my constant questions during the period of writing my thesis. His comments were valuable as they enabled me to go through the right way of doing things in my thesis. He was such a great supporter for me throughout my journey. I would also like to thank the internal examiner Dr. Abd Alkareem Daraghmeh at An-Najah National University. His suggestions, comments, and insights helped me improve this study in terms of form and content. -

NEOLOGISMS in SOCIAL NETWORKING AMONG YOUTHS Sakina Shahlee & Rosniah Mustaffa

TRYAKSH INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF MULTIDISCIPLINARY (TIJM) http://tryakshpublications.com/journals/single/Multidisciplinary NEOLOGISMS IN SOCIAL NETWORKING AMONG YOUTHS Sakina Shahlee & Rosniah Mustaffa Abstract Neologism refers to a newly formed word that accommodates the usage of a language at a particular time. Some of the newly formed words are not established. However, due to their significant use, they are widely accepted in social networking. Social networking has greatly impacted everyone especially the youths. The limitations set by certain social networking platforms escalate the formation of neologisms. This paper aims to examine the neologisms used by youth on social networking platforms in terms of morphological process and word class. Data were collected from a group of students majoring in English at one of the local university in Malaysia. 90 neologisms were identified and captured through several social networking platforms. Findings revealed that youth tends to create new words by using acronym process. Moreover, most of the neologisms formed are verbs. This study enlightens on the use of neologisms among youth on social networking platforms. Besides, it contributes to the chronological history of the English language. Keywords: Neologism, morphological process, social networking, English language 1. INTRODUCTION Neologisms are fabricated in many ways (Peterson & Ray, 2013). Neologisms have different word structures and various With the emerging social networks and technology, processes are implemented to form the word structurally. The communication between people regardless of the geographical processes are termed as morphological processes. Some distance becomes easier and smoother. Communication utilises neologisms are formulated based on entirely new lexical items vocabularies, and some of the new vocabularies, words or and some are altered according to the existing established terms used are not even officially established and recorded in words. -

Stop Talking About Fake News!

Stop Talking about Fake News! Joshua Habgood-Coote, University of Bristol Forthcoming in Inquiry Abstract Since 2016, there has been an explosion of academic work and journalism that fixes its subject matter using the terms ‘fake news’ and ‘post-truth’. In this paper, I argue that this terminology is not up to scratch, and that academics and journalists ought to completely stop using the terms ‘fake news’ and ‘post-truth’. I set out three arguments for abandonment. First, that ‘fake news’ and ‘post-truth’ do not have stable public meanings, entailing that they are either nonsense, context-sensitive, or contested. Secondly, that these terms are unnecessary, because we already have a rich vocabulary for thinking about epistemic dysfunction. Thirdly, I observe that ‘fake news’ and ‘post-truth’ have propagandistic uses, meaning that using them legitimates anti-democratic propaganda, and runs the risk of smuggling bad ideology into conversations. Introduction There are two kinds of approach that one can take when theorising with natural language. One approach is to be a gardener, who respects the complexity and organic unity of natural language. The gardener takes pains to understands subtle distinctions, and takes a conservative attitude that is wary of drastic change. The paradigm example of this methodology is ordinary language philosophy. J.L. Austin stressed that ordinary language embodies the wisdom of collective experience, and took great pains to peel apart everyday distinctions, such as the difference between saying that someone did something by accident, and saying that they did it by mistake (Austin 1956). Another approach is to be a forest manager, who tries to maintain a traversable linguistic landscape by trying to control and shape language. -

English Loanwords in the Chinese Lexicon

ENGLISH LOANWORDS IN THE CHINESE LEXICON Aantal woorden: 30.900 Ruth Vervaet Studentennummer: 01203789 Promotor: Prof. dr. Christoph Anderl Masterproef voorgelegd voor het behalen van de graad master in de richting Oosterse Talen en Culturen: China Academiejaar: 2016 - 2017 Foreword My personal interest in language and linguistic exchanges formed the starting point for this thesis. It has always fascinated me how vocabulary flows from one language to another and how this process takes place. That is why I chose to investigate the presence of English loanwords in the contemporary Chinese lexicon as subject for my master thesis in Oriental Languages and Cultures at Ghent University. I tried to investigate the historical and social background of English loanwords, but the main focus is on the several borrowing methods that are used for the translation of English terms into Chinese. This thesis was written under the guidance of Professor Doctor Christoph Anderl, an expert on Chinese (Medieval) language. I want to thank Professor Anderl from the bottom of my heart for all his help and support. He is a wonderful and kind person who always gives feedback in the most positive way imaginable. Sometimes I was really struggling with writing this thesis and with myself. I could not have finished it without the support of my friends who kept believing in me. Thank you Sara, Lore, Tanita, Nele, Laura, Stan, and all the others. And of course my family: thank you Mam, Dad & Mem for making our home a warm place, a comfortable and stable surrounding. All my love for my sweet Inaya, the sunshine in my life, the one person who motivates me on a daily basis to work hard and become a better person.