LÓPEZ-CALVO, IGNACIO. Written in Exile. Chilean Fiction from 1973-Present

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

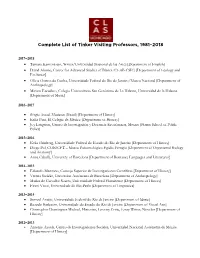

Complete List of Tinker Visiting Professors, 1981–2018

Complete List of Tinker Visiting Professors, 1981–2018 2017–2018 • Tamara Kamenszain, Writer/Universidad Nacional de las Artes [Department of English] • David Alonso, Center for Advanced Studies of Blanes (CEAB-CSIC) [Department of Ecology and Evolution] • Olívia Gomes da Cunha, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro/Museu Nacional [Department of Anthropology] • Miriam Escudero, Colegio Universitario San Gerónimo de La Habana, Universidad de la Habana [Department of Music] 2016–2017 • Sérgio Assad, Musician (Brazil) [Department of History] • Erika Pani, El Colegio de México [Department of History] • Joy Langston, Centro de Investigación y Docencia Económicas, Mexico [Harris School of Public Policy] 2015–2016 • Keila Grinberg, Universidade Federal do Estado do Rio de Janeiro [Department of History] • Diego Pol, CONICET – Museo Paleontológico Egidio Feruglio [Department of Organismal Biology and Anatomy] • Anna Caballé, University of Barcelona [Department of Romance Languages and Literatures] 2014–2015 • Eduardo Manzano, Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas [Department of History] • Verena Stolcke, Universitat Autónoma de Barcelona [Department of Anthropology] • Mariza de Carvalho Soares, Universidade Federal Fluminense [Department of History] • Evani Viotti, Universidade de São Paulo [Department of Linguistics] 2013–2014 • Samuel Araújo, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro [Department of Music] • Ricardo Basbaum, Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro [Department of Visual Arts] • Christopher Domínguez Michael, Historian, -

Figures of the Eternal Return and the Apocalypse in Chilean Post-Dictatorial Fiction

Studies in 20th Century Literature Volume 23 Issue 2 Article 2 6-1-1999 An Anatomy of Marginality: Figures of the Eternal Return and the Apocalypse in Chilean Post-Dictatorial Fiction Idelber Avelar Tulane University Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/sttcl Part of the Latin American Literature Commons, and the Modern Literature Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Avelar, Idelber (1999) "An Anatomy of Marginality: Figures of the Eternal Return and the Apocalypse in Chilean Post-Dictatorial Fiction," Studies in 20th Century Literature: Vol. 23: Iss. 2, Article 2. https://doi.org/10.4148/2334-4415.1464 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in 20th Century Literature by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact [email protected]. An Anatomy of Marginality: Figures of the Eternal Return and the Apocalypse in Chilean Post-Dictatorial Fiction Abstract The article analyzes two novels by Chilean writer Diamela Eltit from the standpoint of the post-dictatorial imperative to mourn the dead and reactivate collective memory. After framing Eltit's fiction in the context of the avant-garde resurgence of plastic and performance arts in the second half of Pinochet's regime, I move on to discuss Lumpérica (1983) and Los vigilantes (1994) as two different manifestations of the temporality of mourning. The article addresses how Lumpérica's portrayal of an oneiric, orgiastic communion in marginality (shared by the protagonist and a mass of beggars at a Santiago square) composed an allegory in the strict Benjaminian sense; it further notes how such allegory, as an anti- dictatorial, oppositional gesture, could only find a home in a temporality modeled after the eternal return. -

The Post-Dictatorial Thriller Form

THE POST-DICTATORIAL THRILLER FORM A Dissertation by AUDREY BRYANT POWELL Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2012 Major Subject: Hispanic Studies The Post-Dictatorial Thriller Form Copyright 2012 Audrey Bryant Powell THE POST-DICTATORIAL THRILLER FORM A Dissertation by AUDREY BRYANT POWELL Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved by: Chair of Committee, Alberto Moreiras Committee Members, Juan Carlos Galdo Teresa Vilarós Andrew Kirkendall Head of Department, Alberto Moreiras May 2012 Major Subject: Hispanic Studies iii ABSTRACT The Post-Dictatorial Thriller Form. (May 2012) Audrey Bryant Powell, B.A., Baylor University; M.A., Baylor University Chair of Advisory Committee: Dr. Alberto Moreiras This dissertation proposes a theoretical examination of the Latin American thriller through the framework of post-dictatorial Chile, with a concluding look at the post civil war Central American context. I define the thriller as a loose narrative structure reminiscent of the basic detective story, but that fuses the conventional investigation formula with more sensational elements such as political violence, institutional corruption and State terrorism. Unlike the classic form, in which crime traditionally occurs in the past, the thriller form engages violence as an event ongoing in the present or always lurking on the narrative horizon. The Chilean post-dictatorial and Central American postwar histories contain these precise thriller elements. Throughout the Chilean military dictatorship (1973-1990), the Central American civil wars (1960s-1990s) and the triumph of global capitalism, political violence emerges in diversified and oftentimes subtle ways, demanding new interpretational paradigms for explaining its manifestation in contemporary society. -

10/2020 Curriculum Vitae MARIA ROSA OLIVERA-WILLIAMS

1 10/2020 Curriculum Vitae MARIA ROSA OLIVERA-WILLIAMS UNIVERSITY OF NOTRE DAME DEPARTMENT OF ROMANCE LANGUAGES AND LITERATURES NOTRE DAME, IN 46556 (574) 631-7268 E-MAIL: [email protected] 2013 PROFESSOR OF LATIN AMERICAN LITERATURE, Department of Romance Languages and Literatures, University of Notre Dame. 1988-present FACULTY FELLOW, Helen Kellogg Institute for International Studies. 2004-present FELLOW, Nanovic Institute for European Studies. EDUCATION Ph.D. Latin American and Peninsular Literatures (Presidential Award) The Ohio State University M.A. Latin American and Peninsular Literatures The Ohio State University, March B.A.S. Spanish (Magna Cum Laude) University of Toledo, Toledo, Ohio PUBLICATIONS Books Humanidades al límite: posiciones desde/contra la universidad global. Introduction and compilation. Co-edition with Cristián Opazo. Santiago, Chile: Cuarto Propio (2021 forthcoming). This volume studies from different perspectives and geographies the roles of Catholic universities to face the crisis of the Humanities in the midst of the challenges and opportunities offered by globalization. The volume reunites the work of distinguished historians, philosophers, literary and cultural studies colleagues at different stages in their careers. El arte de crear lo femenino: ficción, género e historia del Cono Sur. Santiago, Chile: Cuarto Propio, 2012. 257pp. https://www.cuartopropio.com/libro/el-arte-de-crear-lo-femenino/ The book is a theoretical and applied study of women’s social movements and fiction narratives during the second half of the twentieth century in the Southern Cone countries of Latin America, focusing on the post- suffragist period and the military dictatorship and post-dictatorship period. Reviewed by: Magdalena López. -

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Ono Tupuna, the richness of the ancestors. Multiples Landscapes Relationalities in Contemporary Indigenous Rapa Nui Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4kk483h5 Author Rivas, Antonia Publication Date 2017 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Ono Tupuna, the richness of the ancestors. Multiples Landscapes Relationalities in Contemporary Indigenous Rapa Nui By Antonia Rivas A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of degree requirements for Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Charles L Briggs, Co-Chair Professor Nancy Scheper-Hughes, Co-Chair Professor Laura Nader Professor Leti P Volpp Summer 2017 Abstract Ono Tupuna, the richness of the ancestors. Multiples Landscapes Relationalities in Contemporary Indigenous Rapa Nu By Antonia Rivas Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology University of California, Berkeley Professor Charles Briggs, Co-Chair Professor Nancy Scheper-Hughes, Co-Chair Contemporary Rapa Nui is formed by a multiple and complex set of interactions, encounters, and circumstances that comprise the core of their indigenous identity, like many other indigenous people's realities. In this dissertation, I argue that there is not a simple or straightforward way of thinking about indigenous identities without falling into the trap of essentialism and stereotyping. Indigenous people are not what remained of ancestral civilizations, nor are they either invented nor folklorized commodities produced by ―neo-shamanism‖ discourses. Recent theoretical contributions to the understanding of the relationship of native peoples with their territories have been fundamental to rethinking the meanings of indigeneity, but I argue that they continue to essentialize indigenous people relations with their past and the ways in which they are understood in the present. -

New Constructions of House and Home in Contemporary Argentine and Chilean Cinema (2005-2015)

New Constructions of House and Home in Contemporary Argentine and Chilean Cinema (2005-2015) Paul Rumney Merchant St John’s College August 2017 This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. New Constructions of House and Home in Contemporary Argentine and Chilean Cinema (2005 – 2015) Paul Rumney Merchant This thesis explores the potential of domestic space to act as the ground for new forms of community and sociability in Argentine and Chilean films from the early twenty-first century. It thus tracks a shift in the political treatment of the home in Southern Cone cinema, away from allegorical affirmations of the family, and towards a reflection on film’s ability to both delineate and disrupt lived spaces. In the works examined, the displacement of attention from human subjects to the material environment defamiliarises the domestic sphere and complicates its relation to the nation. The house thus does not act as ‘a body of images that give mankind proofs or illusions of stability’ (Bachelard), but rather as a medium through which identities are challenged and reformed. This anxiety about domestic space demands, I argue, a renewal of the deconstructive frameworks often deployed in studies of Latin American culture (Moreiras, Williams). The thesis turns to new materialist theories, among others, as a supplement to deconstructive thinking, and argues that theorisations of cinema’s political agency must be informed by social, economic and urban histories. The prominence of suburban settings moreover encourages a nuancing of the ontological links often invoked between cinema, the house, and the city. The first section of the thesis rethinks two concepts closely linked to the home: memory and modernity. -

Diálogo De La Lengua. Blanca Berasategui Y Jorge Edwards Sobre

w Wl^' Blanca Berasategui nació en Vitoria y Jorge Edwards nació en Santiago de Chile estudió la carrera de Periodismo en y está considerado uno de los grandes Madrid. Ha ejercido gran parte de su escritores en lengua española. Fue Premio vida profesional en la sección de cultura Nacional de Literatura en 1994 y Premio del diario español ABC donde, a partir Miguel de Cervantes en 1999. Estudio de 1980, fue responsable de sus páginas derecho y filosofía y fiíe miembro del literarias. En 1991 creó ABC Cultural, Servicio Exterior chileno desde 1958 hasta publicación que recibió bajo su direc el golpe de Estado de 11973. Es autor de ción numerosos galardones. Blanca cuentos, novelas, ensayos, memorias y ha Berasategui ha trabajado también en sido profesor visitante en diversas universi espacios culturales de radio y televisión, dades europeas y norteamericanas. Su ha dirigido durante dos años la revista de principales novelas son El peso de la noche. pensamiento Cuenta y Razón y es autora Los convidados de piedra. El museo de cera, del libro Gente de palabra. Ha obtenido El anfitrión. La mujer imaginaria. El origen el premio de periodismo Luca de Tena y, del mundo. El Sueño de la Historia, la polé en 2004, el Javier Bueno al mejor perio mica Persona non grata, sobre Cuba, Adiós dismo especializado, que concede la poeta., una evocación de Neruda, que Asociación de la Prensa de Madrid. mereció el premio Comillas, y El inútil de Desde 1999 dirige la revista El Cultural. la familia, de reciente aparición. Durante que aparece todos los jueves en el perió la dictadura de Pinochet fue presidente del dico español El Mundo. -

Cátedra UNESCO Miguel De Cervantes

Cátedra UNESCO “Miguel de Cervantes” Discursos pronunciados en la ceremonia de celebración del Día de la Lengua Española UNESCO 28 de abril de 1992 Compuesto c impreso en los tallcres de la UNESCO O UNESCO 1992 Prinled in Frnnce Portada: Retrato de Miguel de Cervantes. Colección de la Real Academia Española, Madrid. (Foto cortesía de la Sociedad Cervantina y de la Delegación de España ante la UNESCO) Índice Discurso del Excmo. Sr. Federico Mayor, Director General de la Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Educación, la Ciencia y la Cultura (UNESCO) 13 Discurso del Excmo. Sr. Salvador Romero Pittari, Embajador de Bolivia ante la UNESCO y Presidente del Comité del Idioma Español 25 Disertación sobre “Orden y aventura de la lengua” por el Excmo. Sr. Jorge Edwards, Miembro de la Academia Chilena de la Lengua 33 De izquierda a derecha: el Excmo. Sr. Henri Lopes, Subdirector General de Cultura de la UNESCO; la Excma.Sra. Rurh Lerner de Almea, Embajadora de Venezuela en la UNESCO; el Excmo. Sr. Eduardo Portella, Direcror General Adjunto de la UNESCO; el Excmo. Sr. Jorge Edwards, Miembro de la Academia Chilena de la Lengua; el Excmo. Sr. Federico Mayor, Director General de la UNESCO; el Excmo. Sr. Salvador Romero Pittari, Embajador de Bolivia anXe la UNESCO y Prcsidcnte del Comité del Idioma Español; el Excmo. Sr. Félix Fernández-Shaw,Embajador de España en la UNESCO; el Excmo. Sr. Gonzalo Figucroa,Embajador de Chile en la UNESCO. [Foto: UNESCO/lnezForbes) Discurso del Excmo. Sr. Federico Mayor Director General de la UNESCO pronunciado en la Cátedra UNESCO “Miguel de Cervantes” Excmo. -

Bibliografía De Jorge Edwards

BIBLIOGRAFÍA DE JORGE EDWARDS LIBROS Adiós poeta. Barcelona: Tusquets, 2004 Anfitrión, El. Esplugues de Llobregat, Barcelona: Plaza & Janés, 1985 Casa de Dostoievsky, La. Barcelona: Planeta, 2008 Círculos morados, Los. Barcelona: Lumen, 2013 Círculos morados, Los. Barcelona: Lumen, 2012 Convidados de piedra, Los. Barcelona: Círculo de Lectores, [1993] Convidados de piedra, Los. Barcelona: Seix Barral, 1978 Convidados de piedra, Los. Esplugues de Llobregat, Barcelona: Plaza & Janés, 1985 Convidados de piedra, Los. Madrid: Cátedra, [2001] Cuentos completos. Esplugues de Llobregat, Barcelona: Plaza & Janés, 1990 Descubrimiento de la pintura, El. [Barcelona]: Lumen, 2013 Desde la cola del dragón. Barcelona: Dopesa, 1977 Diálogos en un tejado. Barcelona: Tusquets, 2003 Fantasmas de carne y hueso. Barcelona: Tusquets, 1993 Gente de la ciudad. [Santiago de Chile] Editorial Universitaria [1961] Inútil de la familia, El. [Madrid]: Alfaguara, [2005] Inútil de la familia, El. Madrid: Punto de Lectura, [2006] Máscaras, Las. Barcelona: Bruguera, 1981 Máscaras, Las. Madrid: Fondo de Cultura Económica de España Alcalá de Henares: Ediciones de la Universidad de Alcalá de Henares, 2000 Mujer imaginaria, La. Esplugues de Llobregat, Barcelona: Plaza & Janés, 1985 Muerte de Montaigne, La. Barcelona: Tusquets, 2011 Museo de cera, El. [Barcelona]: Bibliotex, [2001] Museo de cera, El. [Santiago de Chile]: Seix Barral, 1985 Instituto Cervantes. Departamento de Bibliotecas y Documentación. Página 1 Museo de cera, El. Barcelona: Bruguera, 1981 Museo de cera, El. Barcelona: Planeta, 2000 Museo de cera, El. Barcelona: Tusquets, 2000 Origen del mundo, El. [Barcelona]: Orbis, [1997] Origen del mundo, El. Barcelona: Tusquets, 1996 Patio, El. Santiago de Chile: Ganymedes, 1980 Persona non grata. Barcelona: Debolsillo, 2013 Persona non grata. -

TRENDS in the CHILEAN SHORT STORY T

Trends in the Chilean short story Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Gregg, Karl Curtiss, 1932- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 09/10/2021 07:04:19 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/319078 TRENDS IN THE CHILEAN SHORT STORY by Karl C. Gregg A Thesis submitted to the faculty of the Department of Spanish in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the Graduate College, University of Arizona 1954 Approved t Director of Thesl/s Ate This thesis- has: heen submit ted,in partial.. fulfillment of requirements for an s^dva.nee.d- degree at the University of V Arizona and is deposited in the Library:to be made.avail able to borrowers under , rules,, of the Library« Brief quotations from this -thesis are allowable.without special p ermiasion 9 provided .that. aoeurate . acknowledgement, of source, is made<, Requests for permisslon, for extended quotation from or reproduction of this ’ manuscript in -.whole or in. part may be granted by the head of the major depart ment or the dean of,the Graduate Oollege when in their judgement the proposed use'of the. material is in the, interests of scholarship.« In all other instances 9 however $ permission must be obtained from the authoro ■ f v . -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Neoliberalism and its Discontents: Three Decades of Chilean Women’s Poetry (1980-2010) Bárbara Fernández Melleda School of Literatures, Languages and Cultures PhD in Hispanic Studies The University of Edinburgh 2018 DECLARATION This is to certify that the work contained within has been composed by me and is entirely my own work. No part of this thesis has been submitted for any other degree or professional qualification. Signed: Bárbara Fernández Melleda ABSTRACT This thesis explores reactions of Chilean women’s poetry to neoliberalism in three chronological stages between 1980 and 2010. The first one focuses upon the years between 1980 and 1990 with the poems Bobby Sands desfallece en el muro (1983) by Carmen Berenguer and La bandera de Chile (1981) by Elvira Hernández, which are analysed in Chapters 2 and 3. -

The New Essential Guide to Spanish Reading

The New Essential Guide to Spanish Reading Librarians’ Selections AMERICA READS SPANISH www.americareadsspanish.org 4 the new essential guide to spanish reading THE NEW ESSENTIAL GUIDE TO SPANISH READING: Librarian’s Selections Some of the contributors to this New Essential Guide to Spanish Reading appeared on the original guide. We have maintained some of their reviews, keeping the original comment and library at the time. ISBN 13: 978-0-9828388-7-7 Edited by Lluís Agustí and Fundación Germán Sánchez Ruipérez Translated by Eduardo de Lamadrid Revised by Alina San Juan © 2012, AMERICA READS SPANISH © Federación de Gremios de Editores de España (FGEE) © Instituto Español de Comercio Exterior (ICEX) Sponsored by: All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, or incorporated into any information retrieval system, electronic or mechanical, without the written permission of the copyright owner. This is a non commercial edition and is not for sale. For free copies of this book, contact the Trade Commission of Spain in Miami at: TRADE COMMISSION OF SPAIN 2655 LeJeune Rd, Suite 1114 CORAL GABLES, FL 33134 Tel. (305) 446-4387 e-mail: [email protected] www.americareadsspanish.org America Reads Spanish is the name of the campaign sponsored by the Spanish Institute for Foreign Trade and the Spanish Association of Publishers Guilds, whose purpose is to increase the reading and use of Spanish through the auspices of thousands of libraries, schools and booksellers in the United States. Printed in the United States of America www.americareadsspanish.org the new essential guide to spanish reading 5 General Index INTRODUCTIONS Pg.