Mediaclips 2 15 2012.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Poetry Project Newsletter

THE POETRY PROJECT NEWSLETTER $5.00 #212 OCTOBER/NOVEMBER 2007 How to Be Perfect POEMS BY RON PADGETT ISBN: 978-1-56689-203-2 “Ron Padgett’s How to Be Perfect is. New Perfect.” —lyn hejinian Poetry Ripple Effect: from New and Selected Poems BY ELAINE EQUI ISBN: 978-1-56689-197-4 Coffee “[Equi’s] poems encourage readers House to see anew.” —New York Times The Marvelous Press Bones of Time: Excavations and Explanations POEMS BY BRENDA COULTAS ISBN: 978-1-56689-204-9 “This is a revelatory book.” —edward sanders COMING SOON Vertigo Poetry from POEMS BY MARTHA RONK Anne Boyer, ISBN: 978-1-56689-205-6 Linda Hogan, “Short, stunning lyrics.” —Publishers Weekly Eugen Jebeleanu, (starred review) Raymond McDaniel, A.B. Spellman, and Broken World Marjorie Welish. POEMS BY JOSEPH LEASE ISBN: 978-1-56689-198-1 “An exquisite collection!” —marjorie perloff Skirt Full of Black POEMS BY SUN YUNG SHIN ISBN: 978-1-56689-199-8 “A spirited and restless imagination at work.” Good books are brewing at —marilyn chin www.coffeehousepress.org THE POETRY PROJECT ST. MARK’S CHURCH in-the-BowerY 131 EAST 10TH STREET NEW YORK NY 10003 NEWSLETTER www.poetryproject.com #212 OCTOBER/NOVEMBER 2007 NEWSLETTER EDITOR John Coletti WELCOME BACK... DISTRIBUTION Small Press Distribution, 1341 Seventh St., Berkeley, CA 94710 4 ANNOUNCEMENTS THE POETRY PROJECT LTD. STAFF ARTISTIC DIRECTOR Stacy Szymaszek PROGRAM COORDINATOR Corrine Fitzpatrick PROGRAM ASSISTANT Arlo Quint 6 WRITING WORKSHOPS MONDAY NIGHT COORDINATOR Akilah Oliver WEDNESDAY NIGHT COORDINATOR Stacy Szymaszek FRIDAY NIGHT COORDINATOR Corrine Fitzpatrick 7 REMEMBERING SEKOU SUNDIATA SOUND TECHNICIAN David Vogen BOOKKEEPER Stephen Rosenthal DEVELOpmENT CONSULTANT Stephanie Gray BOX OFFICE Courtney Frederick, Erika Recordon, Nicole Wallace 8 IN CONVERSATION INTERNS Diana Hamilton, Owen Hutchinson, Austin LaGrone, Nicole Wallace A CHAT BETWEEN BRENDA COULTAS AND AKILAH OLIVER VOLUNTEERS Jim Behrle, David Cameron, Christine Gans, HR Hegnauer, Sarah Kolbasowski, Dgls. -

Jack C. Ellis and Betsy A. Mclane

p A NEW HISTORY OF DOCUMENTARY FILM Jack c. Ellis and Betsy A. McLane .~ continuum NEW YOR K. L ONDON - Contents Preface ix Chapter 1 Some Ways to Think About Documentary 1 Description 1 Definition 3 Intellectual Contexts 4 Pre-documentary Origins 6 Books on Documentary Theory and General Histories of Documentary 9 Chapter 2 Beginnings: The Americans and Popular Anthropology, 1922-1929 12 The Work of Robert Flaherty 12 The Flaherty Way 22 Offshoots from Flaherty 24 Films of the Period 26 Books 011 the Period 26 Chapter 3 Beginnings: The Soviets and Political btdoctrinatioll, 1922-1929 27 Nonfiction 28 Fict ion 38 Films of the Period 42 Books on the Period 42 Chapter 4 Beginnings: The European Avant-Gardists and Artistic Experimentation, 1922-1929 44 Aesthetic Predispositions 44 Avant-Garde and Documentary 45 Three City Symphonies 48 End of the Avant-Garde 53 Films of the Period 55 Books on the Period 56 v = vi CONTENTS Chapter 5 Institutionalization: Great Britain, 1929- 1939 57 Background and Underpinnings 57 The System 60 The Films 63 Grierson and Flaherty 70 Grierson's Contribution 73 Films of the Period 74 Books on the Period 75 Chapter 6 Institutionalization: United States, /930- 1941 77 Film on the Left 77 The March of Time 78 Government Documentaries 80 Nongovernment Documentaries 92 American and British Differences 97 Denouement 101 An Aside to Conclude 102 Films of the Period 103 Books on the Period 103 Chapter 7 Expansion: Great Britain, 1939- 1945 105 Early Days 106 Indoctrination 109 Social Documentary 113 Records of Battle -

Winter. 2017 Volume

IN THIS ISSUE ASSOCIATION OF MOVING IMAGE ARCIVISTS AMIA DAS New York, May - 5 May 5th at MoMA in New York City. From the Board From the 2016 Annual Report ALSO … Note from the Board 2 Conference Wrap Up 2 Awards 4 Images from Pittsburgh 8 AMIA 2016 Wrap Up Member News 12 Page 2 News from the Field 14 Winter. 2017 Volume 114 News from the Field Page 14 AMIA NEWSLETTER | Volume 114 2 From the AMIA Board From the AMIA Annual Report AMIA 2015 had a record attendance in Portland nearly a year ago when this current board took office. At that business meeting a group members challenged the organization to make changes to make the Association more inclusive, accessible and affordable. This conference we will focus on diversity, inclusion and equity and discuss action steps moving forward. We have inaugurated a sliding scale for conference fees and will open a full day of programming free to the community while live-streaming those sessions for those not able to attend. Collaborative notetaking and online presentations post-conference will also offer those resources beyond conference attendees and the membership. If you viewed the organization solely through the lens of this year’s lively debates on our list-servs and in social media you would miss all the incredible work by our committees and members, the support for the association that has come through new partners and strong collaborators, and a series of major events brought together voices from every corner of our field. It humbles me how much energy and creative initiative the members of AMIA have. -

Documentary Screens: Non-Fiction Film and Television

Documentary Screens Non-Fiction Film and Television Keith Beattie 0333_74117X_01_preiv.qxd 2/19/04 8:59 PM Page i Documentary Screens This page intentionally left blank 0333_74117X_01_preiv.qxd 2/19/04 8:59 PM Page iii Documentary Screens Non-Fiction Film and Television Keith Beattie 0333_74117X_01_preiv.qxd 2/19/04 8:59 PM Page iv © Keith Beattie 2004 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No paragraph of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4LP. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The author has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published 2004 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS and 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010 Companies and representatives throughout the world PALGRAVE MACMILLAN is the global academic imprint of the Palgrave Macmillan division of St. Martin’s Press, LLC and of Palgrave Macmillan Ltd. Macmillan® is a registered trademark in the United States, United Kingdom and other countries. Palgrave is a registered trademark in the European Union and other countries. ISBN 0–333–74116–1 hardback ISBN 0–333–74117–X paperback This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. -

EL DOCUMENTAL: Historia, Teoría Y Práctica

EL DOCUMENTAL: Historia, Teoría y Práctica (Asignatura "Realización de Documental", 4º curso) Dr. Demetrio E. BRISSET Deptº de Comunicación Audiovisual y Publicidad Facultad de Ciencias de la Comunicación Universidad de Málaga TEMARIO 0. INTRODUCCIÓN a) Los nuevos activistas ...………………… 8 b) La credibilidad: ficción y no-ficción …………………… 10 c) Definiciones del documental …………………… 14 d) Ficha para analizar documentales …………………… 16 TEMA 1 a) El cine como representación de la realidad …………………… 22 b) El montaje como principio organizativo ………………..….. 30 c) Los 'modos de representación' de Nichols …………………… 35 TEMA 2 Bases teóricas y evolución histórica de los documentales ……………. 39 TEMA 3 El documentalismo en España I (orígenes, república, franquismo) ….. 51 TEMA 4 Influencia del cine sobre el documental moderno (marlowe62) …….. 59 TEMA 5 El documental como revelador y como ensayo …………………… 86 TEMA 6 El documentalismo en España II (el nuevo documentalismo) ……… 88 TEMA 7 Tendencias actuales: a) Los Web-docs (R. Arnau) …………………… 92 b) Los falsos o Mock documentaries (Univ. Berkeley) ………… 105 c) Found footage o Metraje encontrado (M. Alberdi) ………... 138 d) Nuevas tendencias formales en el siglo XXI (A. Vidal) ……. 140 BIBLIOGRAFÍA …………….. 152 Créditos de las ilustraciones …………….. 154 REALIZACIÓN DE DOCUMENTAL: Visionados Presentación de documental hecho por escolares: Massó no recordo (2014, 19’) 0. INTRODUCCIÓN “Fahrenheit 9/11” (Michael Moore, 2004): íntegro 0.b) “Semana Santa en Sevilla” (Hnos. Lumiérè, 1898) Films de T. A. Edison sobre la guerra España-USA (1898) Falso noticiero inicial en "Citizen Kane” (O. Welles, 1941) Trailer de ”F for or Fake" (O. Welles, 1973) Polémica sobre el falso docum. "Operación Palace" (2014) "Kuidado ke muerden" (Colectivo RuidoFoto, 2012): 17' "Human" (Yann Arthus-Bertrand, 2015): íntegro "7 billion others" (Y. -

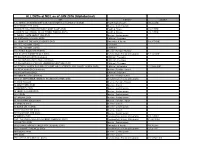

Listing by Director-Title-Year-Country-Length Director Program Name Year Country Length

Listing by Director-Title-Year-Country-Length Director Program Name Year Country Length * A Midsummer Nights Dream 1981 UK 112 min * Adam: Giselle (Dutch National Ballet) 2010 NL 114 min * Alfred Hitchcock Presents: Season 1 1955 USA 566 min * Alfred Hitchcock Presents: Season 2 1956 USA 1014 min * Alfred Hitchcock Presents: Season 3 1957 USA 1041 min * Alfred Hitchcock Presents: Season 4 1958 USA 931 min * Alfred Hitchcock Presents: Season 5 1959 USA 985 min * Amsterdam 1928 "The IX Olympiad in Amsterdam" 1928 NL 251 min * Art Blakey & The Jazz Messengers Live in '58 2006 BE 55 min * As You Like It 1978 UK 150 min * Avengers, The: 1965, Set 1 (6 Episodes) 1965 UK 156 min * Avengers, The: 1965, Set 2 (7 Episodes) 1965 UK 182 min * Avengers, The: 1966, Set 1 (6 Episodes) 1966 UK 156 min * Avengers, The: 1966, Set 2 (7 Episodes) 1966 UK 182 min * Avengers, The: 1967, Set 1 (6 Episodes) 1967 UK 156 min * Avengers, The: 1967, Set 2 (6 Episodes) 1967 UK 156 min * Beckett DVD No. 1 2003 UK 225 min * Beckett DVD No. 2 2003 UK 151 min * Beckett DVD No. 3 2003 UK 142 min * Beckett DVD No. 4 2003 UK 127 min * Berlioz: Les Troyens 2010 UK 314 min * Bonus Disc: Coltrane -Gordon-Brubeck-Vaughan 2007 SE NO FI 35 min * Buddy Rich Live in '78 2006 USA 75 min Monday, August 2, 2021 Page 1 of 125 Director Program Name Year Country Length * Busoni: Doktor Faust 2006 CH 215 min * Canada: A People's History Series 1 Episodes 01-05 2001 CA 575 min * Canada: A People's History Series 2 Episodes 06-09 2001 CA 460 min * Canada: A People's History Series 3 Episodes -

Title 16Mm Rental 16Mm Sale Video Rental Video Sale

16MM VIDEO VIDEO TITLE RENTAL 16MM SALE RENTAL SALE A APPLY A AND B IN ONTARIO $32 -- -- A LA MODE $25 -- -- AARON SISKIND $50 $30 $110 AARON SISKIND: MAKING PICTURES $70 $40 $125 ABOVE US THE EARTH $90 -- -- ACADEMY LEADER VARIATIONS $40 -- -- AEROS -- $75 $175 AFTER MONGOLFIER -- $40 -- AFTERGLOW: A TRIBUTE TO ROBERT FROST, THE $50 $25 $110 AFTERNOON $125*** -- -- AGE DOOR, L' (Rental: see GEORGE GRIFFIN PROGRAM III) -- -- -- AGE OF STEEL: DIEGO RIVERA, THE $60 $50 $150 AGNES DEI KINDER SYNAPSE $20 -- -- AI-YE $50 -- -- ALADDIN $40 -- -- ALBERT SCHWEITZER -- $65 $200 ALBERTO GIACOMETTI $40 -- -- ALEX KATZ PAINTING $55 $30 -- ALEXANDER ALEXEIEFF PROGRAM $50 -- -- ALEXANDER CALDER: CALDER'S UNIVERSE $85 $50 $375 ALEXANDER CALDER: SCULPTURE AND CONSTRUCTIONS $30 -- -- ALEXANDER NEVSKY $125 -- -- ALFRED STIEGLITZ: PHOTOGRAPHER $85 $50 $375 ALIAS JIMMY VALENTINE (35mm only) $130 -- -- ALICE NEEL $40 -- $125 ALL MY BABIES $60 $160 ALL MY LIFE $25 -- -- ALLEGRETTO (Rental: see OSKAR FISCHINGER PROGRAM II) -- -- -- ALONE AND THE SEA $33 -- -- ALOUETTE $25 -- -- AMELIA AND THE ANGEL $35 -- -- AMERICA $65 -- -- AMERICA IS HARD TO SEE $160 -- -- AMERICA TODAY and THE WORLD IN REVIEW (Rental: see FILM AND PHOTO LEAGUE PROGRAM II) -- -- -- AMERICAN MARCH, AN (Rental: see OSKAR FISCHINGER PROGRAM II) -- -- -- AMERICAN MUSICALS: FAMOUS PRODUCTION NUMBERS $70 -- -- AMERICAN POTTER, AN $48 -- $125 AMERICA'S POP COLLECTOR $150 -- $200 AMITIE NOIRE, L' $30 -- -- AMOR PEDESTRE $25 -- -- AMY! $65 -- -- ANALOGIES # 1 $30 -- -- AND SO THEY LIVE $35 -- -- -

Documentary 101: a Viewer's Guide to Non

In the 21st century, documentary films are more popular than ever, while carrying on a venerable artistic tradition that emphasizes humanism and social advocacy. DOCUMENTARY 101 is a first-ever anthology of this crucial cinematic field, covering the entire spectrum of non-fiction film with entries on over 300 titles from 1895 to 2012. There are 101 full-length reviews of documentaries chosen for their aesthetic prominence and/or historical significance, followed by briefer entries on related titles. Documentary 101 Order the complete book from Booklocker.com http://www.booklocker.com/p/books/6965.html?s=pdf or from your favorite neighborhood or online bookstore. Your free excerpt appears below. Enjoy! Documentary 101: A Viewer’s Guide to Non-Fiction Film Rick Ouellette Copyright © 2013 Rick Ouellette ISBN 978-1-62646-423-0 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the author. Published by BookLocker.com, Inc., Bradenton, Florida. Printed in the United States of America. BookLocker.com, Inc. 2013 First Edition Table of Contents INTRODUCTION .............................................................................. 1 #1 THE LUMIÈRE BROTHERS’ FILMS ......................................... 7 LUMIERE & COMPANY .............................................................................. 8 #2 NANOOK OF THE NORTH ....................................................... -

Here a Group of Drunks Are Arguing Loudly

A Milestone Films Release • www.milestonefilms.com • www.ontheboweryfilm.com A Milestone Films release ON THE BOWERY 1956. USA. 65 minutes. 35mm. Aspect ratio: 1:1.33. Black and White. Mono. World Premiere: 1956, Venice Film Festival Selected in 2008 for the National Film Registry by the Library of Congress Winner of the Grand Prize in Documentary & Short Film Category, Venice Film Festival, 1956. British Film Academy Award, “The Best Documentary of 1956.” British Film Festival, 1957. Nominated for American Academy Award, Best Documentary, 1958. A Milestone Films theatrical release: October 2010. ©1956 Lionel Rogosin Productions, Inc. All rights reserved. The restoration of On the Bowery has been encouraged by Rogosin Heritage Inc. and carried out by Cineteca del Comune di Bologna. The restoration is based on the original negatives preserved at the Anthology Film Archives in New York City. The restoration was carried out at L’Immagine Ritrovata laboratory. The Men of On the Bowery Ray Salyer Gorman Hendricks Frank Matthews Dedicated to: Gorman Hendricks Crew: Produced & Directed by .............Lionel Rogosin In collaboration with ...................Richard Bagley and Mark Sufrin Technical Staff ............................Newton Avrutis, Darwin Deen, Lucy Sabsay, Greg Zilboorg Jr., Martin Garcia Edited by ......................................Carl Lerner Music............................................Charles Mills Conducted by...............................Harold Gomberg The Perfect Team: The Making of On The Bowery 2009. France/USA/Italy. 46:30 minutes. Digital. Aspect Ratio: 1:1.85. Color/B&W. Stereo. Produced and directed by Michael Rogosin. Rogosin interviews by Marina Goldovskaya. Edited by Thierry Simonnet. Assistant Editor: Céleste Rogosin. Cinematography and sound by Zach Levy, Michael Rogosin, Lloyd Ross. Research and archiving: Matt Peterson. -

Stanley Kubrick: Producers and Production Companies

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by De Montfort University Open Research Archive Stanley Kubrick: Producers and Production Companies Thesis submitted by James Fenwick In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy De Montfort University, September 2017 1 Abstract This doctoral thesis examines filmmaker Stanley Kubrick’s role as a producer and the impact of the industrial contexts upon the role and his independent production companies. The thesis represents a significant intervention into the understanding of the much-misunderstood role of the producer by exploring how business, management, working relationships and financial contexts influenced Kubrick’s methods as a producer. The thesis also shows how Kubrick contributed to the transformation of industrial practices and the role of the producer in Hollywood, particularly in areas of legal authority, promotion and publicity, and distribution. The thesis also assesses the influence and impact of Kubrick’s methods of producing and the structure of his production companies in the shaping of his own reputation and brand of cinema. The thesis takes a case study approach across four distinct phases of Kubrick’s career. The first is Kubrick’s early years as an independent filmmaker, in which he made two privately funded feature films (1951-1955). The second will be an exploration of the Harris-Kubrick Pictures Corporation and its affiliation with Kirk Douglas’ Bryna Productions (1956-1962). Thirdly, the research will examine Kubrick’s formation of Hawk Films and Polaris Productions in the 1960s (1962-1968), with a deep focus on the latter and the vital role of vice-president of the company. -

Listing by Title-Director-Cinematographer-Editor-Writer Title Director Cinematographer Editor Writer

Listing by Title-Director-Cinematographer-Editor-Writer Title Director Cinematographer Editor Writer ...And the Pursuit of Happiness Malle, Louis Malle, Louis Baker, Nancy * ¡Alambrista! Young, Robert M. Hurwitz, Tom; Robert M. Young Beyer, Edward Young, Robert M. 10 Rillington Place Fleischer, Richard Coop , Denys N. Walter, Ernest Kennedy , Ludovic; Clive Exton 10:30 PM Summer Dassin, Jules Pogány, Gábor Dwyre, Roger Duras, Marguerite; Jules Dassin 10th Victim, The Petri, Elio Di Venanzo, Gianni Mastroianni , Ruggero Sheckley, Robert; Tonino Guerra; Giorgio Salvioni, e 12 Angry Men Lumet, Sidney Kaufman, Boris Lerner , Carl Rose, Reginald 1900 Bertolucci, Bernardo Storaro, Vittorio Arcalli, Franco Arcalli, Franco; Bernardo Bertolucci 1917 Mendes, Sam Deakins, Roger Smith, Lee Mendes, Sam; Krysty Wilson-Cairns 1984 Radford, Michael Deakins, Roger Priestley, Tom Radford, Michael; George Orwell 2 or 3 Things I Know About Her Godard, Jean-Luc Coutard, Raoul Collin, Françoise Godard, Jean-Luc 20 Million Miles to Earth Juran, Nathan Lippman, Irving; Carlo Ventimiglia Bryant, Edwin H. Williams, Robert Creighton; Christopher Knopf 2001: A Space Odyssey [4K UHD] Kubrick, Stanley Unsworth, Geoffrey Lovejoy, Ray Clarke, Arthur; Stanley Kubrick 2046 Wong, Kar Wai Doyle, Christopher; Pung-Leung Kwan Chang, William Wong, Kar Wai 21 Grams Iñárritu, Alejandro González Prieto, Rodrigo; Fortunato Procopio Mirrione, Stephen Arriaga, Guillermo 23 Paces to Baker Street Hathaway, Henry Krasner, Milton R. Clark, James B. Balchin, Nigel; Philip MacDonald 24 City Zhangke, Jia Wang, Yu; Nelson Yu Lik-wai Kong, Jing Lei; Xudong Lin Zhang-ke, Jia; Yongming Zhai 24 Frames Kiarostami, Abbas * * * 25th Hour Lee, Spike Prieto, Rodrigo Brown, Barry Alexander Benioff, David 3 Godfathers Ford, John Hoch, Winton C. -

Dvds at MCL As of JAN 2016

ALL DVDs at MCL as of JAN 2016 (Alphabetical) Title Category DEWEY 1 2 3 MAGIC: MANAGING DIFFICULT BEHAVIOR IN CHILDREN 2-12 (DVD) Psychological Issues 649.64 ONE 10 ITEMS OR LESS (DVD) Movies - Contemporary 10 MINUTE SOLUTION: HOT BODY BOOT CAMP (DVD) Health & Fitness 613.71 TEN 10 MINUTE SOLUTIONS: QUICK TUMMY TONERS (DVD) Health & Fitness 613.71 TEN 10 THINGS I HATE ABOUT YOU (DVD) Movies - Contemporary 100 CARTOON CLASSICS (DVD) Children's Programs 100 YEARS OF THE WORLD SERIES (DVD) Recreation & Sports 796.357 ONE 100, THE: SEASON 1 (DVD) Television 100, THE: SEASON 2 (DVD) Television 1000 TIMES GOOD NIGHT (DVD) Movies - Foreign - Norway 1001 CLASSIC COMMERCIALS (DVD) Documentary, History & Biography 659.143 ONE 101 DALMATIANS (DVD) (Animated) Children's Programs 101 DALMATIANS (DVD) (Diamond Edition) Children's Programs 101 DALMATIANS II: PATCH'S LONDON ADVENTURE (DVD) Children's Programs 101 FITNESS GAMES FOR KIDS AT CAMP VOL 5: STRENTH AND AGILITY GAMES (DVD) Children's Information 613.7042 ONE 101 REYKJAVIK (DVD) (Icelandic) Movies - Foreign - Iceland 102 DALMATIANS (DVD) Children's Programs 11 FLOWERS (DVD) (Chinese) Movies - Foreign - China 11TH OF SEPTEMBER: MOYERS IN CONVERSATION (DVD) Documentary, History & Biography 12 (DVD) (Russian) Movies - Foreign - Russia 12 ANGRY MEN (DVD) Movies - Classic 12 MONKEYS (DVD) Movies - Contemporary 12 YEARS A SLAVE (DVD) Movies - Contemporary 12:01 (DVD) Movies - Contemporary 127 HOURS (DVD) Movies - Contemporary 13 ASSASSINS (DVD)(Japan) Movies - Foreign - Japan 13 GHOSTS (DVD) Movies