Caffeine Caused a Widespread Increase of Resting Brain Entropy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cuban Human Brain Mapping Project Population Based Normative EEG, MRI, and Cognition Dataset

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.08.194290; this version posted July 10, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. The Cuban Human Brain Mapping Project population based normative EEG, MRI, and Cognition dataset. Authors: Pedro A. Valdes-Sosa1,2*+, Lidice Galan2*, Jorge Bosch-Bayard3,2,1*, Maria L. Bringas Vega1,2*, Eduardo AuBert Vazquez2*, Samir Das3, Trinidad Virues AlBa2, Cecile MadJar3, Zia Mohades3, Leigh C. MacIntyre3, Christine Rogers3, Shawn Brown3, Lourdes Valdes Urrutia2, Iris Rodriguez Gil2, Alan C. Evans3+, Mitchell J. Valdes Sosa1,2+ *Co-first authors +Co-corresponding authors Affiliations: 1The Clinical Hospital of Chengdu Brain Sciences, University of Electronic Sciences and Technology of China, Chengdu China 2CuBan Center for Neuroscience, La Habana, CuBa 3McGill Centre for Integrative Neurosciences MCIN. Ludmer Centre for Mental Health. Montreal Neurological Institute, McGill University, Montreal, Canada Abstract The CuBan Human Brain Mapping ProJect (CHBMP) repository is an open multimodal neuroimaging and cognitive dataset from 282 healthy participants (31.9 ± 9.3 years, age range 18–68 years). This dataset was acquired from 2004 to 2008 as a suBset of a larger stratified random sample of 2,019 participants from La Lisa municipality in La Habana, CuBa. The exclusion included presence of disease or Brain dysfunctions. The information made available for all participants comprises: high-density (64-120 channels) resting state electroencephalograms (EEG), magnetic resonance images (MRI), psychological tests (MMSE, Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale -WAIS III, computerized reaction time tests using a go no- go paradigm), as well as general information (age, gender, education, ethnicity, handedness and weight). -

Ultra-High-Field Imaging Reveals Increased Whole Brain Connectivity

RESEARCH ARTICLE Ultra-high-field imaging reveals increased whole brain connectivity underpins cognitive strategies that attenuate pain Enrico Schulz1,2*, Anne Stankewitz2, Anderson M Winkler1,3, Stephanie Irving2, Viktor Witkovsky´ 4, Irene Tracey1 1Wellcome Centre for Integrative Neuroimaging, FMRIB, Nuffield Department of Clinical Neurosciences, University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom; 2Department of Neurology, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universita¨ t Mu¨ nchen, Munich, Germany; 3Emotion and Development Branch, National Institute of Mental Health, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, United States; 4Department of Theoretical Methods, Institute of Measurement Science, Slovak Academy of Sciences, Bratislava, Slovakia Abstract We investigated how the attenuation of pain with cognitive interventions affects brain connectivity using neuroimaging and a whole brain novel analysis approach. While receiving tonic cold pain, 20 healthy participants performed three different pain attenuation strategies during simultaneous collection of functional imaging data at seven tesla. Participants were asked to rate their pain after each trial. We related the trial-by-trial variability of the attenuation performance to the trial-by-trial functional connectivity strength change of brain data. Across all conditions, we found that a higher performance of pain attenuation was predominantly associated with higher functional connectivity. Of note, we observed an association between low pain and high connectivity for regions that belong to brain regions long associated with pain processing, the insular and cingulate cortices. For one of the cognitive strategies (safe place), the performance of pain attenuation was explained by diffusion tensor imaging metrics of increased white matter integrity. *For correspondence: [email protected] Competing interests: The Introduction authors declare that no An increased perception of pain is generally associated with increased cortical activity; this has been competing interests exist. -

Neuroimage: Clinical

NEUROIMAGE: CLINICAL AUTHOR INFORMATION PACK TABLE OF CONTENTS XXX . • Description p.1 • Audience p.1 • Impact Factor p.1 • Abstracting and Indexing p.2 • Editorial Board p.2 • Guide for Authors p.4 ISSN: 2213-1582 DESCRIPTION . NeuroImage: Clinical,, a companion title to the highly-respected NeuroImage, is a journal of diseases, disorders and syndromes involving the Nervous System, provides a vehicle for communicating important advances in the study of abnormal structure-function relationships of the human nervous system based on imaging. The focus of NeuroImage: Clinical is on defining changes to the brain associated with primary neurologic and psychiatric diseases and disorders of the nervous system as well as behavioral syndromes and developmental conditions. The main criterion for judging papers is the extent of scientific advancement in the understanding of the pathophysiologic mechanisms of diseases and disorders, in identification of functional models that link clinical signs and symptoms with brain function and in the creation of image based tools applicable to a broad range of clinical needs including diagnosis, monitoring and tracking of illness, predicting therapeutic response and development of new treatments. Papers dealing with structure and function in animal models will also be considered if they reveal mechanisms that can be readily translated to human conditions. The journal welcomes original research articles as well as papers on innovative methods, models, databases, theory or conceptual positions provided that they involve imaging approaches and demonstrate significant new opportunities for understanding clinical problems. AUDIENCE . Academic and clinical Neurologists and Psychiatrists working with brain imaging techniques, Imaging Neuroscientists, Cognitive Neuroscientists, Experimental Psychologists, Computational Neuroscientists, System Neuroscientists, Social Neuroscientists, Biostatisticians. -

Standardizing Human Brain Parcellations

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/845065; this version posted November 26, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. Standardizing Human Brain Parcellations Patrick E. Myers1, Ganesh C. Arvapalli1, Sandhya C.Ramachandran1, Derek A. Pisner2, Paige F. Frank1, Allison D. Lemmer1, Eric W. Bridgeford1, Aki Nikolaidis3, Joshua T. Vogelstein1, ∗ Abstract. Using brain atlases to localize regions of interest is a required for making neuroscientifically valid statistical infer- ences. These atlases, represented in volumetric or surface coordinate spaces, can describe brain topology from a variety of perspectives. Although many human brain atlases have circulated the field over the past fifty years, limited effort has been devoted to their standardization and specification. The purpose of standardization and specifica- tion is to ensure consistency and transparency with respect to orientation, resolution, labeling scheme, file storage format, and coordinate space designation. Consequently, researchers are often confronted with limited knowledge about a given atlas’s organization, which make analytic comparisons more difficult. To fill this gap, we consolidate an extensive selection of popular human brain atlases into a single, curated open-source library, where they are stored following a standardized protocol with accompanying metadata. We propose that this protocol serves as the basis for storing future atlases. To demonstrate the utility of storing and standardizing these atlases following a common protocol, we conduct an experiment using data from the Healthy Brain Network whereby we quantify the statistical dependence of each atlas label on several key phenotypic variables. -

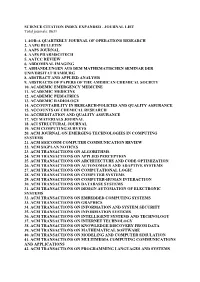

SCIENCE CITATION INDEX EXPANDED - JOURNAL LIST Total Journals: 8631

SCIENCE CITATION INDEX EXPANDED - JOURNAL LIST Total journals: 8631 1. 4OR-A QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF OPERATIONS RESEARCH 2. AAPG BULLETIN 3. AAPS JOURNAL 4. AAPS PHARMSCITECH 5. AATCC REVIEW 6. ABDOMINAL IMAGING 7. ABHANDLUNGEN AUS DEM MATHEMATISCHEN SEMINAR DER UNIVERSITAT HAMBURG 8. ABSTRACT AND APPLIED ANALYSIS 9. ABSTRACTS OF PAPERS OF THE AMERICAN CHEMICAL SOCIETY 10. ACADEMIC EMERGENCY MEDICINE 11. ACADEMIC MEDICINE 12. ACADEMIC PEDIATRICS 13. ACADEMIC RADIOLOGY 14. ACCOUNTABILITY IN RESEARCH-POLICIES AND QUALITY ASSURANCE 15. ACCOUNTS OF CHEMICAL RESEARCH 16. ACCREDITATION AND QUALITY ASSURANCE 17. ACI MATERIALS JOURNAL 18. ACI STRUCTURAL JOURNAL 19. ACM COMPUTING SURVEYS 20. ACM JOURNAL ON EMERGING TECHNOLOGIES IN COMPUTING SYSTEMS 21. ACM SIGCOMM COMPUTER COMMUNICATION REVIEW 22. ACM SIGPLAN NOTICES 23. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON ALGORITHMS 24. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON APPLIED PERCEPTION 25. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON ARCHITECTURE AND CODE OPTIMIZATION 26. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON AUTONOMOUS AND ADAPTIVE SYSTEMS 27. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON COMPUTATIONAL LOGIC 28. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON COMPUTER SYSTEMS 29. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON COMPUTER-HUMAN INTERACTION 30. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON DATABASE SYSTEMS 31. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON DESIGN AUTOMATION OF ELECTRONIC SYSTEMS 32. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON EMBEDDED COMPUTING SYSTEMS 33. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON GRAPHICS 34. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON INFORMATION AND SYSTEM SECURITY 35. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON INFORMATION SYSTEMS 36. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON INTELLIGENT SYSTEMS AND TECHNOLOGY 37. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON INTERNET TECHNOLOGY 38. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON KNOWLEDGE DISCOVERY FROM DATA 39. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON MATHEMATICAL SOFTWARE 40. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON MODELING AND COMPUTER SIMULATION 41. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON MULTIMEDIA COMPUTING COMMUNICATIONS AND APPLICATIONS 42. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON PROGRAMMING LANGUAGES AND SYSTEMS 43. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON RECONFIGURABLE TECHNOLOGY AND SYSTEMS 44. -

Combining Brain Perturbation and Neuroimaging in Non-Human Primates

1 Brain Perturbation and Neuroimaging in NHPs 1 2 Combining Brain Perturbation and Neuroimaging in Non-human Primates 3 P. Christiaan Klink1,*, Jean-François Aubry2, Vincent P. Ferrera3, Andrew S. Fox4, Sean Froudist-Walsh5, 4 Bechir Jarraya6,7, Elisa Konofagou8, Richard Krauzlis9, Adam Messinger10, Anna S. Mitchell11, Michael 5 Ortiz-Rios12,13, Hiroyuki Oya14, Angela C. Roberts15, Anna Wang Roe16, Matthew F. S. Rushworth11, Jérôme 6 Sallet11,17, Michael Christoph Schmid12,18, Charles E. Schroeder19, Jordy Tasserie6, Doris Tsao20, Lynn Uhrig6, 7 Wim Vanduffel21, Melanie Wilke13,22, Igor Kagan13,* & Christopher I. Petkov12,* 8 REVISION 1 2021-03-07 9 10 Author affiliations 11 1 Department of Vision & Cognition, Netherlands Institute for Neuroscience, Amsterdam, The Netherlands 12 2 Physics for Medicine Paris, Inserm U1273, CNRS UMR 8063, ESPCI Paris, PSL University, Paris, France 13 3 Department of Neuroscience & Department of Psychiatry, Columbia University Medical Center, New York, NY, 14 USA; Zuckerman Mind Brain Behavior Institute, Columbia University, New York, NY, USA 15 4 Department of Psychology & California National Primate Research Center, University of California, Davis, CA, USA 16 5 Center for Neural Science, New York University, New York, NY, USA 17 6 NeuroSpin, Commissariat à l'Énergie Atomique et aux Énergies Alternatives (CEA), Institut National de la Santé et de 18 la Recherche Médicale (INSERM), Cognitive Neuroimaging Unit, Université Paris-Saclay, France; 19 7 Foch Hospital, UVSQ, Suresnes, France 20 8 Ultrasound and -

Top Peer Reviewed Journals – Neuroscience & Behavior

Top Peer Reviewed Journals – Neuroscience & Behavior Presented to Iowa State University Presented by Thomson Reuters Neuroscience & Behavior The subject discipline for Neuroscience & Behavior is made of 5 narrow subject categories from the Web of Science. The 5 categories that make up Neuroscience & Behavior are: 1. Behavioral Sciences 4. Neurosciences 2. Clinical Neurology 5. Psychology, Biological 3. Neuroimaging The chart below provides an ordered view of the top peer reviewed journals within the 1st quartile for Neuroscience & Behavior based on Impact Factors (IF), three year averages and their quartile ranking. Journal 2009 IF 2010 IF 2011 IF Average IF NATURE REVIEWS NEUROSCIENCE 26.48 29.51 30.44 28.81 ANNUAL REVIEW OF NEUROSCIENCE 24.82 26.75 25.73 25.77 BEHAVIORAL AND BRAIN SCIENCES 19.04 21.95 25.05 22.01 MOLECULAR PSYCHIATRY 15.04 15.47 13.66 14.72 NATURE NEUROSCIENCE 14.34 14.19 15.53 14.69 NEURON 13.26 14.02 14.73 14.00 TRENDS IN NEUROSCIENCES 12.79 13.32 14.23 13.45 FRONTIERS IN NEUROENDOCRINOLOGY 12.04 12.75 11.42 12.07 ANNALS OF NEUROLOGY 9.31 10.74 11.08 10.38 BRAIN 9.49 9.23 9.45 9.39 PROGRESS IN NEUROBIOLOGY 9.14 9.96 8.87 9.32 BRAIN RESEARCH REVIEWS 7.39 8.84 10.34 8.86 BIOLOGICAL PSYCHIATRY 8.92 8.67 8.28 8.62 NEUROSCIENCE AND BIOBEHAVIORAL 7.79 9.01 8.65 8.48 REVIEWS NEUROLOGY 8.17 8.01 8.31 8.16 ACTA NEUROPATHOLOGICA 6.39 7.69 9.32 7.80 NEUROPSYCHOPHARMACOLOGY 6.99 6.68 7.99 7.22 JOURNAL OF NEUROSCIENCE 7.17 7.27 7.11 7.18 CURRENT OPINION IN NEUROBIOLOGY 7.21 6.89 7.44 7.18 ARCHIVES OF NEUROLOGY 6.31 7.1 7.58 7.00 -

Redalyc.Connectivity of BA46 Involvement in the Executive Control

Psicothema ISSN: 0214-9915 [email protected] Universidad de Oviedo España Ardila, Alfredo; Bernal, Byron; Rosselli, Monica Connectivity of BA46 involvement in the executive control of language Psicothema, vol. 28, núm. 1, 2016, pp. 26-31 Universidad de Oviedo Oviedo, España Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=72743610004 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Alfredo Ardila, Byron Bernal and Monica Rosselli Psicothema 2016, Vol. 28, No. 1, 26-31 ISSN 0214 - 9915 CODEN PSOTEG Copyright © 2016 Psicothema doi: 10.7334/psicothema2015.174 www.psicothema.com Connectivity of BA46 involvement in the executive control of language Alfredo Ardila1, Byron Bernal2 and Monica Rosselli3 1 Florida International University, 2 Miami Children’s Hospital and 3 Florida Atlantic University Abstract Resumen Background: Understanding the functions of different brain areas has Estudio de la conectividad del AB46 en el control ejecutivo del lenguaje. represented a major endeavor of contemporary neurosciences. Modern Antecedentes: la comprensión de las funciones de diferentes áreas neuroimaging developments suggest cognitive functions are associated cerebrales representa una de las mayores empresas de las neurociencias with networks rather than with specifi c areas. Objectives. The purpose contemporáneas. Los estudios contemporáneos con neuroimágenes of this paper was to analyze the connectivity of Brodmann area (BA) 46 sugieren que las funciones cognitivas se asocian con redes más que con (anterior middle frontal gyrus) in relation to language. -

NIMG-10-2549R2 Title: Characterization of Group

Elsevier Editorial System(tm) for NeuroImage Manuscript Draft Manuscript Number: NIMG-10-2549R2 Title: Characterization of groups using composite kernels and multi-source fMRI analysis data: application to schizophrenia Article Type: Regular Article Section/Category: Methods & Modelling Corresponding Author: Mr. Eduardo Castro, M.Sc. Corresponding Author's Institution: University of New Mexico First Author: Eduardo Castro, M.Sc. Order of Authors: Eduardo Castro, M.Sc.; Manel Martinez-Ramon, PhD; Godfrey Pearlson, MD; Jing Sui, PhD; Vince D Calhoun, PhD Abstract: Pattern classification of brain imaging data can enable the automatic detection of differences in cognitive processes of specific groups of interest. Furthermore, it can also give neuroanatomical information related to the regions of the brain that are most relevant to detect these differences by means of feature selection procedures, which are also well-suited to deal with the high dimensionality of brain imaging data. This work proposes the application of recursive feature elimination using a machine learning algorithm based on composite kernels to the classification of healthy controls and patients with schizophrenia. This framework, which evaluates nonlinear relationships between voxels, analyzes whole-brain fMRI data from an auditory task experiment that is segmented into anatomical regions and recursively eliminates the uninformative ones based on their relevance estimates, thus yielding the set of most discriminative brain areas for group classification. The collected data was processed using two analysis methods: the general linear model (GLM) and independent component analysis (ICA). GLM spatial maps as well as ICA temporal lobe and default mode component maps were then input to the classifier. A mean classification accuracy of up to 95% estimated with a leave-two-out cross-validation procedure was achieved by doing multi-source data classification. -

Functional Neuroimaging 1 Fundamentals Of

FUNCTIONAL NEUROIMAGING 1 FUNDAMENTALS OF FUNCTIONAL NEUROIMAGING Stephan Geuter1 Martin A. Lindquist2 Tor D. Wager1,3* 1University of Colorado Boulder, Institute of Cognitive Science 2Johns Hopkins University, Department of Biostatistics 3University of Colorado Boulder, Department of Psychology and Neuroscience Summary: 21303 words (text, without references) 26058 total words (with references) 3 tables 11 figures Running head: FUNCTIONAL NEUROIMAGING * Address correspondence to: Dr. Tor D. Wager Department of Psychology and Neuroscience University of Colorado Boulder 345 UCB Boulder, CO 80309 E-mail: tor.wager@ colorado.edu. FUNCTIONAL NEUROIMAGING 2 Acknowledgments We would like to thank Jessica Andrews-Hanna for helpful comments on the manuscript. Parts of this chapter are adapted from Wager. T. D., Hernandez, L., and Lindquist, M.A. (2009). Essentials of functional neuroimaging. In: G. G. Berntson and J. T. Cacioppo (Eds.), Handbook of Neuroscience for the Behavioral Sciences. (pp. 152-97). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. FUNCTIONAL NEUROIMAGING 3 I. Introduction ................................................................................................................. 5 II. Overview of Neuroimaging Techniques .................................................................... 6 Measures available on MR and PET scanners .................................................... 7 Structural images ............................................................................................ 7 Diffusion weighted imaging (DWI) ............................................................... -

Source Publication List for Web of Science

SOURCE PUBLICATION LIST FOR WEB OF SCIENCE SCIENCE CITATION INDEX EXPANDED Updated July 2017 Journal Title Publisher ISSN E-ISSN Country Language 2D Materials IOP PUBLISHING LTD 2053-1583 2053-1583 ENGLAND English 3 Biotech SPRINGER HEIDELBERG 2190-572X 2190-5738 GERMANY English 3D Printing and Additive Manufacturing MARY ANN LIEBERT, INC 2329-7662 2329-7670 UNITED STATES English 4OR-A Quarterly Journal of Operations Research SPRINGER HEIDELBERG 1619-4500 1614-2411 GERMANY English AAPG BULLETIN AMER ASSOC PETROLEUM GEOLOGIST 0149-1423 1558-9153 UNITED STATES English AAPS Journal SPRINGER 1550-7416 1550-7416 UNITED STATES English AAPS PHARMSCITECH SPRINGER 1530-9932 1530-9932 UNITED STATES English AATCC Journal of Research AMER ASSOC TEXTILE CHEMISTS COLORISTS-AATCC 2330-5517 2330-5517 UNITED STATES English AATCC REVIEW AMER ASSOC TEXTILE CHEMISTS COLORISTS-AATCC 1532-8813 1532-8813 UNITED STATES English Abdominal Radiology SPRINGER 2366-004X 2366-0058 UNITED STATES English ABHANDLUNGEN AUS DEM MATHEMATISCHEN SEMINAR DER UNIVERSITAT HAMBURG SPRINGER HEIDELBERG 0025-5858 1865-8784 GERMANY German ABSTRACTS OF PAPERS OF THE AMERICAN CHEMICAL SOCIETY AMER CHEMICAL SOC 0065-7727 UNITED STATES English Academic Pediatrics ELSEVIER SCIENCE INC 1876-2859 1876-2867 UNITED STATES English Accountability in Research-Policies and Quality Assurance TAYLOR & FRANCIS LTD 0898-9621 1545-5815 UNITED STATES English Acoustics Australia SPRINGER 1839-2571 1839-2571 AUSTRALIA English Acta Bioethica UNIV CHILE, CENTRO INTERDISCIPLINARIO ESTUDIOS BIOETICA 1726-569X -

Elsevier Editorial(Tm) for Neuroimage Manuscript Draft

Elsevier Editorial(tm) for NeuroImage Manuscript Draft Manuscript Number: NIMG-04-81R1 Title: Distinct unimodal and multimodal regions for word processing in the left temporal cortex Article Type: Regular Article Keywords: Corresponding Author: Dr. Laurent Cohen Hôpital de la Salpêtrière Other Authors: Antoinette Jobert; Denis Le Bihan, MD, PhD; Stanislas Dehaene, PhD , , * Cover Letter Dear Sir, Thank you for giving us the opportunity to submit a revised version of our paper. We include a detailed cover letter with our responses to all the reviewers’ comments and suggestions. Sincerely Laurent COHEN Service de Neurologie 1 Hôpital de la Salpêtrière 47/83 Bd de l’Hôpital 75651 Paris CEDEX 13, France Tel: 01 42 16 18 49 / 01 42 16 18 02 Fax: 01 44 24 52 47 E-mail: [email protected] * Response to Reviews Response to Reviews Reviewer #2 1. The reviewer observes that our use of the terms “multimodal” and “crossmodal” was somewhat fuzzy and inaccurate. We basically agree, and we therefore modified the text accordingly. We no longer use the word “crossmodal” with reference to cortical areas, but only to effects such as “crossmodal priming”, which reveal the existence of shared representations for auditory and visual words. The word “multimodal” now applies uniformly to anatomical regions activated by both auditory and visual words. Accordingly, we modified the title, checked the entire text, and suppressed from the introduction our initial attempt to define the respective meaning of the two terms when applied to anatomical regions. Note that this terminology conforms to a common usage, and should not be taken to imply any strong theoretical commitment on functional brain organization.