The Julfa Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Armenia 2020 June-11-22, 2020 Tour Conductor and Guide: Norayr Daduryan

Armenia 2020 June-11-22, 2020 Tour conductor and guide: Norayr Daduryan Price ~ $4,000 June 11, Thursday Departure. LAX flight to Armenia. June 12, Friday Arrival. Transport to hotel. June 13, Saturday 09:00 “Barev Yerevan” (Hello Yerevan): Walking tour- Republic Square, the fashionable Northern Avenue, Flower-man statue, Swan Lake, Opera House. 11:00 Statue of Hayk- The epic story of the birth of the Armenian nation 12:00 Garni temple. (77 A.D.) 14:00 Lunch at Sergey’s village house-restaurant. (included) 16:00 Geghard monastery complex and cave churches. (UNESCO World Heritage site.) June 14, Sunday 08:00-09:00 “Vernissage”: open-air market for antiques, Soviet-era artifacts, souvenirs, and more. th 11:00 Amberd castle on Mt. Aragats, 10 c. 13:00 “Armenian Letters” monument in Artashavan. 14:00 Hovhannavank monastery on the edge of Kasagh river gorge, (4th-13th cc.) Mr. Daduryan will retell the Biblical parable of the 10 virgins depicted on the church portal (1250 A.D.) 15:00 Van Ardi vineyard tour with a sunset dinner enjoying fine Italian food. (included) June 15, Monday 08:00 Tsaghkadzor mountain ski lift. th 12:00 Sevanavank monastery on Lake Sevan peninsula (9 century). Boat trip on Lake Sevan. (If weather permits.) 15:00 Lunch in Dilijan. Reimagined Armenian traditional food. (included) 16:00 Charming Dilijan town tour. 18:00 Haghartsin monastery, Dilijan. Mr. Daduryan will sing an acrostic hymn composed in the monastery in 1200’s. June 16, Tuesday 09:00 Equestrian statue of epic hero David of Sassoon. 09:30-11:30 Train- City of Gyumri- Orphanage visit. -

THE ARMENIAN Mirrorc SPECTATOR Since 1932

THE ARMENIAN MIRRORc SPECTATOR Since 1932 Volume LXXXXI, NO. 37, Issue 4679 APRIL 3, 2021 $2.00 Third Dink Murder Trial Verdicts Issued, Dink Family Issues Statement ISTANBUL (MiddleEastEye, Bianet, Dink Fami- ly) — An Istanbul court issued six sentences of life imprisonment and 23 jail terms, while 33 defendants were acquitted on March 26 in the third court case concerning the January 2007 Hrant Dink murder. One individual died during the trial, leading to charges against him being dropped. Among those sentenced were former police chiefs and security officials. Reporters Without Borders (RSF) Representative to Turkey Erol Önderoğlu commented: “The Hrant Dink case is not over. This is the third trial and it does not comprise behind-the-scenes actors who threatened him with a statement, threw him before vi- olent groups as an object of hate or failed to act so that he would get killed. As a matter of fact, the attorneys of the Dink family made an application to the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) last year as they could A cargo plane carrying COVID-19 Vaccines lands in Armenia. not have over 20 officials put on trial.” The 17-year-old Ogun Samast was convicted of the crime in 2011 but it was clear that he could not have Large Shipment of AstraZeneca carried out this alone. The first court ruling was issued Vaccine Arrives in Armenia By Raffi Elliott The shipment, which was initially Agency (EMA). Special to the Mirror-Spectator expected in mid-February, had been At a press conference held in Yere- delayed due to disruptions in the glob- van on Monday, Deputy Director of YEREVAN — A Swiss Air cargo al supply chain. -

EUROPE a Albania • National Historical Museum – Tirana, Albania

EUROPE A Albania • National Historical Museum – Tirana, Albania o The country's largest museum. It was opened on 28 October 1981 and is 27,000 square meters in size, while 18,000 square meters are available for expositions. The National Historical Museum includes the following pavilions: Pavilion of Antiquity, Pavilion of the Middle Ages, Pavilion of Renaissance, Pavilion of Independence, Pavilion of Iconography, Pavilion of the National Liberation Antifascist War, Pavilion of Communist Terror, and Pavilion of Mother Teresa. • Et'hem Bey Mosque – Tirana, Albania o The Et’hem Bey Mosque is located in the center of the Albanian capital Tirana. Construction was started in 1789 by Molla Bey and it was finished in 1823 by his son Ethem Pasha (Haxhi Ethem Bey), great- grandson of Sulejman Pasha. • Mount Dajt – Tirana, Albania o Its highest peak is at 1,613 m. In winter, the mountain is often covered with snow, and it is a popular retreat to the local population of Tirana that rarely sees snow falls. Its slopes have forests of pines, oak and beech. Dajti Mountain was declared a National Park in 1966, and has since 2006 an expanded area of about 29,384 ha. It is under the jurisdiction and administration of Tirana Forest Service Department. • Skanderbeg Square – Tirana, Albania o Skanderbeg Square is the main plaza of Tirana, Albania named in 1968 after the Albanian national hero Skanderbeg. A Skanderbeg Monument can be found in the plaza. • Skanderbeg Monument – Skanderberg Square, Tirana, Albania o The monument in memory of Skanderbeg was erected in Skanderbeg Square, Tirana. -

Collector Coins of the Republic of Armenia 2012

CENTRAL BANK OF THE REPUBLIC OF ARMENIA OF THE REPUBLIC OF ARMENIA 2012 YEREVAN 2013 Arthur Javadyan Chairman of the Central Bank of Armenia Dear reader The annual journal "Collector Coins of the Republic of Armenia 2012" presents the collector coins issued by the Central Bank of Armenia in 2012 on occasion of important celebrations and events of the year. 4 The year 2012 was full of landmark events at both international and local levels. Armenia's capital Yerevan was proclaimed the 12th International Book 2012 Capital, and in the timespan from April 22, 2012 to April 22, 2013 large-scale measures and festivities were held not only in Armenia but also abroad. The book festival got together the world's writers, publishers, librarians, book traders and, in general, booklovers everywhere. The year saw a great diversity of events which were held in cooperation with other countries. Those events included book exhibitions, international fairs, contests ("Best Collector Coins CENTRAL BANK OF THE REPUBLIC OF ARMENIA Literary Work", "Best Thematic Posters"), a variety of projects ("Give-A-Book Day"), workshops, and film premieres. The Central Bank of Armenia celebrated the book festival by issuing the collector coin "500th Anniversary of Armenian Book Printing". In 2012, the 20th anniversaries of formation of Armenian Army and liberation of Shushi were celebrated with great enthusiasm. On this occasion, the Central Bank of Armenia issued the gold and silver coins "20th Anniversary of Formation of Armenian Army" and the gold coin "20th Anniversary of Liberation of Shushi". The 20th anniversary of signing Collective Security Treaty and the 10 years of the Organization of Treaty were celebrated by issuing a collector coin dedicated to those landmark events. -

THE ARMENIAN CULTURAL FOUNDATION Ticipating in Unveiling a Commemorative Plaque Rooms

NOVEMBER 2, 2013 MirTHErARoMENr IAN -Spe ctator Volume LXXXIV, NO. 16, Issue 4310 $ 2.00 NEWS IN BRIEF The First English Language Armenian Weekly in the United States Since 1932 School No. 44 in Nishan Atinizian Yerevan Named for Receives Anania Armenian ‘Orphan Rug’ Is in White House Hrant Dink Shiragatsi Medal from Storage, as Unseen as Genocide Is Neglected YEREVAN (Armenpress) — Mayor of Yerevan Taron Margaryan attended the solemn ceremony WASHINGTON (Washington Post) — The of naming the capital’s school No. 44 after President of Armenia rug was woven by orphans in the 1920s and By Philip Kennicott prominent Armenian journalist and intellectual formally presented to the White House in YEREVAN — Every year, during from Istanbul Hrant Dink this week. The 1925. A photograph shows President Calvin Armenia’s independence celebrations, the Information and Public Relations Department of Coolidge standing on the carpet, which is no mere juvenile effort, but a president of the republic hands out awards the Yerevan Municipality reported that aside complicated, richly detailed work that would hold its own even in the largest to individuals in Armenia and the diaspora from the mayor, Dink’s widow Rackel Dink, par - and most ceremonial who are outstanding in their fields and PHOTO COURTESY OF THE ARMENIAN CULTURAL FOUNDATION ticipating in unveiling a commemorative plaque rooms. have contributed to the betterment of dedicated to Hrant Dink. If you can read a Armenia. Hrant Dink was assassinated in Istanbul in carpet’s cues, the This year, among the honorees singled January 2007, by Ogün Samast, a 17-year old plants and animals out by President Serge Sargisian was Turkish nationalist. -

Museums and Written Communication

Museums and Written Communication Museums and Written Communication: Tradition and Innovation Edited by Nick Winterbotham and Ani Avagyan Museums and Written Communication: Tradition and Innovation Edited by Nick Winterbotham and Ani Avagyan This book first published 2018 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2018 by Nick Winterbotham, Ani Avagyan and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-0755-6 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-0755-5 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements ................................................................................... viii Foreword ........................................................................................................ x Writing and Book within the General Context of the Museum: Speculations on the Problem of the Symposium ................................... 1 Hripsime Pikichian More or Less ................................................................................................ 13 Theodorus Meereboer A Civilisation in Museum Space: Some Theoretical Approaches ... 36 Albert Stepanyan Overcome Your Fears and Start Writing for an Online Community ................................................................................................. -

“Building Bridges, Breaking the Walls: Managing Refugee Crisis in Europe” 2-Stage Project TRAINING COURSE & STUDY VISIT

“Building Bridges, Breaking the Walls: Managing Refugee Crisis in Europe” 2-Stage Project TRAINING COURSE & STUDY VISIT Basic information What: Training Course Title: Building Bridges, Breaking the Walls: Managing Refugee Crisis in Europe Venues and dates: Training Course: 20-28 November (including travel days), Yerevan, Armenia Study Visit: February (days will be confirmed), Stockholm, Sweden Participating Countries: Armenia, Sweden, Norway, Finland, Italy, Moldova, Romania, Ukraine, Denmark, Turkey, Czech Republic, Greece, Germany, Georgia, Portugal Idea, theme and objectives Structure The project is intended for 32 youth workers, youth educators, members of civil society organizations from 15 European Union and the Neighboring countries who are ready to actively fight against radicalization, discrimination and intolerance against refugees and migrants in their countries and who want to transfer the knowledge they gained in the project to the youth in their organizations and countries. NOTE! To ensure a long term impact we will involve same 36 youth workers in both activities of the project. Objectives of the Activity: The Training Course (Armenia) and the Study Visit (Sweden) have the following main objectives: To provide conceptual framework on the notions of emigration, immigration, integration and multiculturalism to 36 youth workers from different European countries; To analyze the emigration and immigration situation in participating countries and to find out the causes of migration, namely push and pull factors; To discuss -

President Kocharian in Working Visit to France Meets President Sarkozy

the armenian Number 20 July 14, 2007 reporter International Will Armenian-Azerbaijani dialogue continue? President Kocharian in On June 28, 2007, a joint Arme- Hrachya Arzumanian, a Step- nian-Azerbaijani delegation visited anakert-based contributor to the working visit to France Karabakh, Armenia, and Azerbai- Armenian Reporter interviewed jan. This initiative was realized Dr. Ludmila Grigorian, a physician after a year and a half of bilateral and civic activist from Stepanakert, discussions. The visited was a de- who was part of this unique del- meets President Sarkozy parture from Azerbaijan’s usual egation. Her thoughts and insight hostile rhetoric and policy. But it make for a compelling story. is still unclear, if the trip will open the way for more dialogue or be- Concludes Year of come an exception from the norm. See story on page A3 m Armenia in France International by Emil Sanamyan Armenian congressional caucus member Rep. PARIS – President Nicolas Sarkozy John Tierney talks about his trip Azerbaijan of France and President Robert Ko- charian of Armenia held an hour- Representative John Tierney (D.- Azerbaijani government put out a long meeting at the Élysée Palace Mass.) has been a longtime sup- press release saying that “consider- on July 12, continuing the close porter of the Armenian causes in ing the activities of the Armenian high-level relationship the two Congress. As part of his work on community” the congressman was countries’ successive leaders have the congressional Select Intel- happy to hear the other side. Our developed over the last decade. ligence Committee, Rep. Tierney Washington Editor Emil Sanamyan “We have reconfirmed all the was in Azerbaijan last week where talked to Rep. -

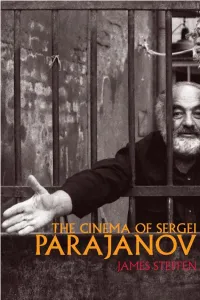

Cinema of Sergei Parajanov Parajanov Performs His Own Imprisonment for the Camera

The Cinema of Sergei Parajanov Parajanov performs his own imprisonment for the camera. Tbilisi, October 15, 1984. Courtesy of Yuri Mechitov. The Cinema of Sergei Parajanov James Steffen The University of Wisconsin Press Publication of this volume has been made possible, in part, through support from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. The University of Wisconsin Press 1930 Monroe Street, 3rd Floor Madison, Wisconsin 53711- 2059 uwpress.wisc .edu 3 Henrietta Street London WC2E 8LU, England eurospanbookstore .com Copyright © 2013 The Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any format or by any means, digital, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, or conveyed via the Internet or a website without written permission of the University of Wisconsin Press, except in the case of brief quotations embedded in critical articles and reviews. Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Steffen, James. The cinema of Sergei Parajanov / James Steffen. p. cm. — (Wisconsin fi lm studies) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978- 0- 299- 29654- 4 (pbk. : alk. paper) — ISBN 978- 0- 299- 29653- 7 (e- book) 1. Paradzhanov, Sergei, 1924–1990—Criticism and interpretation. 2. Motion pictures—Soviet Union. I. Title. II. Series: Wisconsin fi lm studies. PN1998.3.P356S74 2013 791.430947—dc23 2013010422 For my family. Contents List of Illustrations ix -

Caucasus Pearls 15Days € 2061

CAUCASUS PEARLS 15 DAYS Small Group Tour To Azerbaijan-Georgia-Armenia BOOK 6 MONTHS IN ADVANCE SAVE 10% € 2061 Starts from baku every second tuesday The route is open from May to October. Choose the date and join the group in Baku. Combined group tour to 3 South Caucasus countries – Azerbaijan, Georgia and Armenia is special itinerary. Three expert guides will work for you –one local guide in each country . Get acquainted with 3 different cultures, see diversity of traditions and visit the most unique and spectacular sights of these countries. MAIN HIGHLIGHTS & SITES: AZERBAIJAN • Narikala Fortress & Mosque Samtskhe region • Legvtakhevi Waterfall • Borjomi Spa-Resort Baku • Sulfur Bathhouse District • Borjomi- NP • Panorama of the City & Baku Bay • Sharden & King Erekle II street • Akhaltsikhe Town from Mountain park • Sioni & Anchiskhati Basilica • Rabat Castle 14-18th cc • The medieval sight of the Old City • Vardzia Caves 12th c 11-19 cc, Kartli region • Karvansaray Complex 14-15 cc. • Gori J. Stalin Museum ARMENIA • Mosques 11-19cc. • Uplistsikhe Caves 1st C • Old bath, narrow small streets, • Gyumri town Art Shops & Handicraft Workshop Mtskheta CITY • Echmiadzin • Giz Galasi Maiden Tower • Svetitskhoveli of 12th c • Zvartnoc • Gobustan NP of rock painting • Jvari Monastery of 6th c • Yerevan city • Matenadaran museum KAKHETI province SHEKI • History museum • Signagi town & museum • Diri-Baba Mausoleum • Geghard Monastery • Tsinandali • Sheki Fortress • Garni Pagan Temple • Shumi • Sheki Khan Palace • Khor Virap Monastery • Telavi -

White Space Gallery Collection Catalogue

wasEverything forever, nountil more it was WHITE SPACE GALLERY COLLECTION CATALOGUE EVERYTHING WAS FOREVER, CONTENTS UNTIL IT WAS NO MORE White Space Gallery Collection Catalogue Introduction by Dorota Michalska 5 Catalogue and price list 36 © White Space Gallery, 2019 Published in 2019 by White Space Gallery, London UK Non-conformism 9 Yuri Albert 36 [email protected] Ilya Kabakov 9 Tatiana Antoshina 36 www.whitespacegallery.co.uk Mikhail Grobman 9 Yuri Avvakumov 37 Leonid Borisov 38 Introduction by Dorota Michalska Leonid Borisov 9 Antanas Sutkus 10 Vita Buivid 40 Alexander Florenski 40 All images © the artists Moscow Conceptualism 12 Olga Florenski 41 Yuri Albert 12 Images of Timur Novikov’s works: Courtesy of the artist’s Gluklya 42 family collection, St Petersburg, unless otherwise stated. Dmitry Prigov 12 Mihail Grobman 43 Underground Cinema and Alternative Music 15 Book design: mikestonelake.com Ilya Kabakov 43 Andrey Tarkovsky 15 Andrei Krisanov 43 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be Sergei Parajanov 15 Dmitri Konradt 44 reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any Yuri Mechitov 16 Oleg Kotelnikov 45 form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, Vladimir Tarasov 17 recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission in Oleg Kotelnikov & Andrey Medvedev 45 writing of White Space Gallery. Dmitry Konradt 18 Oleg Kulik 46 Perestroika and the Post-Soviet period 21 Stas Makarov 46 Timur Novikov 21 Yuri Mechitov 47 Oleg Kotelnikov 21 Lera Nibiru 48 Ivan Sotnikov 22 Timur -

Yerevan and Was Three Months Renders My Memory Suspect When It Tells Me That We Studying Archeology

DISCOVERING ARMENI D ISCOVERING EDITORIAL For young Armenians today, our homeland can be seen in many different ways. It is seen by some, as a destination visited on a family vacation, or with a graduating class. Comparable to a coming-of-age Euro trip, these visits, despite being limited in scope and depth, can spark an initial connection to a far-away land. To others, Armenia evokes romantic sentiments of a hallowed land, al- most too pristine to be real. Captivated by flawless mental imagery, they may be too apprehensive to see it, lest they leave disappointed by reality. Contributors: To others, it is a foreign place on a map, or a country that exists—by Hermine Avagyan Gayane Khechoomian default—on a list of places to be visited “when we get the chance.” Tamar Baboujian Rouben Krikorian To still others Armenia is a fledgling nation with an ancient history, a coun- Nareg Gourdikian Khatchig Mouradian try of treasures both hidden and in plain sight; treasures from the past and Vrej Haroutounian Ani Sarkisian treasures that are just materializing. Gev Iskajyan Maro Siranosian Shoghak Kazandjian Mariam Soukhoudyan Regardless of background or starting point, discovering Armenia is mean- ingful because it brings to reality the rich history and culture of our people. Layout & Design: Raffi Semerdjian It takes our history out of books and places it in a tangible context that is ours to experience. The firsthand adventure of bringing to life the stories Editor: Vaché Thomassian of our childhood has more value today than ever before, both in terms of feasibility and necessity.