Problematizing the Metaphor of Travel: a Study of the Journeys of Humans and Texts from India to Tibet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RET HS No. 1:RET Hors Série No. 1

Revue d’Etudes Tibétaines Table des Matières récapitulative des nos. 1-15 Hors-série numéro 01 — Août 2009 Table des Matières récapitulative des numéros 1-15 Revue d’Etudes Tibétaines Hors-série no. 1 — Août 2009 ISSN 1768-2959 Directeur : Jean-Luc Achard Comité de rédaction : Anne Chayet, Pierre Arènes, Jean-Luc Achard. Comité de lecture : Pierre Arènes (CNRS), Ester Bianchi (Dipartimento di Studi sull’Asia Orientale, Venezia), Anne Chayet (CNRS), Fabienne Jagou (EFEO), Rob Mayer (Oriental Institute, University of Oxford), Fernand Meyer (CNRS-EPHE), Fran- çoise Pommaret (CNRS), Ramon Prats (Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Barcelona), Brigitte Steinman (Université de Lille) Jean-Luc Achard (CNRS). Périodicité La périodicité de la Revue d’Etudes Tibétaines est généralement bi-annuelle, les mois de parution étant, sauf indication contraire, Octobre et Avril. Les contributions doivent parvenir au moins deux (2) mois à l’avance. Les dates de proposition d’articles au co- mité de lecture sont Février pour une parution en Avril et Août pour une parution en Octobre. Participation La participation est ouverte aux membres statutaires des équipes CNRS, à leurs mem- bres associés, aux doctorants et aux chercheurs non-affiliés. Les articles et autres contributions sont proposées aux membres du comité de lec ture et sont soumis à l’approbation des membres du comité de rédaction. Les arti cles et autres contributions doivent être inédits ou leur ré-édition doit être justifiée et soumise à l’approbation des membres du comité de lecture. Les documents doivent parvenir sous la forme de fichiers Word (.doc exclusive- ment avec fontes unicodes), envoyés à l’adresse du directeur ([email protected]). -

The Prayer, the Priest and the Tsenpo: an Early Buddhist Narrative from Dunhuang

JIABS Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies Volume 30 Number 1–2 2007 (2009) The Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies (ISSN 0193-600XX) is the organ of the International Association of Buddhist Studies, Inc. As a peer-reviewed journal, it welcomes scholarly contributions pertaining to all facets of Buddhist EDITORIAL BOARD Studies. JIABS is published twice yearly. KELLNER Birgit Manuscripts should preferably be sub- KRASSER Helmut mitted as e-mail attachments to: [email protected] as one single fi le, Joint Editors complete with footnotes and references, in two diff erent formats: in PDF-format, BUSWELL Robert and in Rich-Text-Format (RTF) or Open- Document-Format (created e.g. by Open CHEN Jinhua Offi ce). COLLINS Steven Address books for review to: COX Collet JIABS Editors, Institut für Kultur- und GÓMEZ Luis O. Geistesgeschichte Asiens, Prinz-Eugen- HARRISON Paul Strasse 8-10, A-1040 Wien, AUSTRIA VON HINÜBER Oskar Address subscription orders and dues, changes of address, and business corre- JACKSON Roger spondence (including advertising orders) JAINI Padmanabh S. to: KATSURA Shōryū Dr Jérôme Ducor, IABS Treasurer Dept of Oriental Languages and Cultures KUO Li-ying Anthropole LOPEZ, Jr. Donald S. University of Lausanne MACDONALD Alexander CH-1015 Lausanne, Switzerland email: [email protected] SCHERRER-SCHAUB Cristina Web: http://www.iabsinfo.net SEYFORT RUEGG David Fax: +41 21 692 29 35 SHARF Robert Subscriptions to JIABS are USD 40 per STEINKELLNER Ernst year for individuals and USD 70 per year for libraries and other institutions. For TILLEMANS Tom informations on membership in IABS, see back cover. -

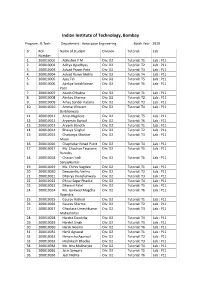

Rolllist Btech DD Bs2020batch

Indian Institute of Technology, Bombay Program : B.Tech. Department : Aerospace Engineering Batch Year : 2020 Sr. Roll Name of Student Division Tutorial Lab Number 1. 200010001 Abhishek P M Div: D2 Tutorial: T1 Lab : P11 2. 200010002 Aditya Upadhyay Div: D2 Tutorial: T2 Lab : P11 3. 200010003 Advait Pravin Pote Div: D2 Tutorial: T3 Lab : P11 4. 200010004 Advait Ranvir Mehla Div: D2 Tutorial: T4 Lab : P11 5. 200010005 Ajay Tak Div: D2 Tutorial: T5 Lab : P11 6. 200010006 Ajinkya Satishkumar Div: D2 Tutorial: T6 Lab : P11 Patil 7. 200010007 Akash Chhabra Div: D2 Tutorial: T1 Lab : P11 8. 200010008 Akshay Sharma Div: D2 Tutorial: T2 Lab : P11 9. 200010009 Amay Sunder Kataria Div: D2 Tutorial: T3 Lab : P11 10. 200010010 Ammar Khozem Div: D2 Tutorial: T4 Lab : P11 Barbhaiwala 11. 200010011 Anup Nagdeve Div: D2 Tutorial: T5 Lab : P11 12. 200010012 Aryaman Bansal Div: D2 Tutorial: T6 Lab : P11 13. 200010013 Aryank Banoth Div: D2 Tutorial: T1 Lab : P11 14. 200010014 Bhavya Singhal Div: D2 Tutorial: T2 Lab : P11 15. 200010015 Chaitanya Shankar Div: D2 Tutorial: T3 Lab : P11 Moon 16. 200010016 Chaphekar Ninad Punit Div: D2 Tutorial: T4 Lab : P11 17. 200010017 Ms. Chauhan Tejaswini Div: D2 Tutorial: T5 Lab : P11 Ramdas 18. 200010018 Chavan Yash Div: D2 Tutorial: T6 Lab : P11 Sanjaykumar 19. 200010019 Ms. Chinni Vagdevi Div: D2 Tutorial: T1 Lab : P11 20. 200010020 Deepanshu Verma Div: D2 Tutorial: T2 Lab : P11 21. 200010021 Dhairya Jhunjhunwala Div: D2 Tutorial: T3 Lab : P11 22. 200010022 Dhruv Sagar Phadke Div: D2 Tutorial: T4 Lab : P11 23. 200010023 Dhwanil Patel Div: D2 Tutorial: T5 Lab : P11 24. -

Pilgrimage to Drakar Dreldzong

Pilgrimage to Drakar Dreldzong The Written Tradition and Contemporary Practices among Amdo Tibetans ,#-7--a};-1 Zhuoma ( |) Thesis Submitted for the Degree of M. Phil in Tibetan Studies Department of Culture Studies and Oriental Languages University of Oslo Spring 2008 1 Summary This thesis focuses on pilgrimage (gnas skor) to Drakar Dreldzong, a Buddhist holy mountain (gnas ri) in a remote area of Amdo, Tibet, in the present day Qinghai Province in the western part of China. The mountain had long been a solitude hermitage and still is a popular pilgrimage site for Tibetan lamas and nearby laymen. Pilgrimage to holy mountains was, and still is, significant for the religious, cultural and literary life of Tibet, and even for today’s economic climate in Tibet. This thesis presents the traditional perceptions of the site reflected both in written texts, namely pilgrimage guides (gnas bshad), and in the contemporary practices of pilgrimage to Drakar Dreldzong. It specifically talks about an early pilgrimage guide (Guide A) written by a tantric practitioner in the early 17th century, and newly developed guides (Guides B, C and D), based on the 17th century one, edited and composed by contemporary Tibetan lay intellectuals and monks from Dreldzong Monastery. This monastery, which follows the Gelukba tradition, was established in 1923 at the foot of the mountain. The section about the early guide mainly introduces the historical framework of pilgrimage guides and provides an impression of the situation of the mountain in from the 17th to the 21st century. In particular, it translates the text and gives comments and analysis on the content. -

The Spiti Valley Recovering the Past & Exploring the Present OXFORD

The Spiti Valley Recovering the Past & Exploring the Present Wolfson College 6 t h -7 t h May, 2016 OXFORD Welcome I am pleased to welcome you to the first International Conference on Spiti, which is being held at the Leonard Wolfson Auditorium on May 6 th and 7 th , 2016. The Spiti Valley is a remote Buddhist enclave in the Indian Himalayas. It is situated on the borders of the Tibetan world with which it shares strong cultural and historical ties. Often under-represented on both domestic and international levels, scholarly research on this subject – all disciplines taken together – has significantly increased over the past decade. The conference aims at bringing together researchers currently engaged in a dialogue with past and present issues pertaining to Spitian culture and society in all its aspects. It is designed to encourage interdisciplinary exchanges in order to explore new avenues and pave the way for future research. There are seven different panels that address the theme of this year’s conference, The Spiti Valley : Recovering the Past and Exploring the Present , from a variety of different disciplinary perspectives including, archaeology, history, linguistics, anthropology, architecture, and art conservation. I look forward to the exchange of ideas and intellectual debates that will develop over these two days. On this year’s edition, we are very pleased to have Professor Deborah Klimburg-Salter from the universities of Vienna and Harvard as our keynote speaker. Professor Klimburg-Salter will give us a keynote lecture entitled Through the black light - new technology opens a window on the 10th century . -

Some Questions Concerning the Ugc Course in Astrology

SOME QUESTIONS CONCERNING THE UGC COURSE IN ASTROLOGY Kushal Siddhanta 18 AUGUST 2001. Dr. Murali Manohar cient Indian astronomer Varahamihira who Joshi, the present Union HRD Minister and in the sixth century AD spoke about the a former professor of physics in the Alla- earth's rotation.” Citing another fact in sup- habad University, was invited to the IIT, port of introducing astrology as a university Kharagpur, as the chief guest at an open- course, he said, 16 universities of the coun- ing function organized on the occasion of try had already been offering astrology as its fiftieth foundation anniversary. The a subject in various forms. So his govern- West Bengal Chief Minister Mr. Buddhadeb ment is doing nothing new. People should Bhattacharya was another guest. not oppose the astrology and other courses only on political reasons. There may be de- As expected, Mr. Bhattacharya in his bates and arguments over the issue. The speech indirectly criticized the policy of the Government, he assured all, was ready to Union Government to introduce worn out hear. So on and so forth. subjects like astrology, paurohitya, vas- tushastra, yoga and human consciousness, It all had started when the UGC issued a etc., in the universities through the Univer- circular on 23 February 2001 with a pro- sity Grant Commission (UGC). Dr. Joshi posal to all the universities of the country in his address, however, did not go into to introduce UG and PG courses as well the trouble of explaining why his depart- as doctoral researches in Vedic Astrology ment was so keen on funding these anti- which it later renamed in parenthesis as quated subjects in the universities in spite Jyotirvigyan (astronomy). -

The Three Sisters in the Ge-Sar Epic

THE THREE-SISTERS IN THE GE-SAR EPIC -Siegbert Hummel In its Mongolian version, as published by I. J. Schmidt in German translation 1, . as well as in the Kalmuk fragments which were made known as early as 1804/0 S by Benjamin Bergmann2 the Ge-sar saga repeatedly mentions three sisters who prompt his actions during his life on earth, who urge him on or rebuke him 3 Not only Ge-sar, but also the giant with whom he enters into combat and finally kills, has three maidens as sisters, and, as can be understood from the action, they are a kind of goddesses of fate who dwell in trees which are to be regarded as the seat ofthe vital-pow~r (Tib.: bla) of the monster, i.e. as socalled bla-gnas or bla-shing. Consequently the giant is brought to the point of ruin by the killing of the maidens and the destruction ot the trees4. \ The three sisters are in all respects to be distinguished from the well-known genii of man who are born together with him and who appear in' the Tibetan judgment of the dead where the good genius, a lha (Skt.: deva), enumerates the good deeds of the deceased by means of white pebbles, while the evil one, a demon (Tib.:' dre), counts the evil actions with black pebb1es S. Nor are the three sisters to be identified wilhthe personal guardian deities of the Tibetans, the 'go-ba'i-1ha, with whom they have certain traiits in common. The group of 'go ha'i -lha normally has five members. -

Codicology, Paleography, and Orthography of Early Tibetan Documents

WIENER STUDIEN ZUR TIBETOLOGIE UND BUDDHISMUSKUNDE HEFT 89 Brandon Dotson and Agnieszka Helman-Ważny CODICOLOGY, PALEOGRAPHY, AND ORTHOGRAPHY OF EARLY TIBETAN DOCUMENTS METHODS AND A CASE STUDY ARBEITSKREIS FÜR TIBETISCHE UND BUDDHISTISCHE STUDIEN UNIVERSITÄT WIEN WIEN 2016 WSTB 89 WIENER STUDIEN ZUR TIBETOLOGIE UND BUDDHISMUSKUNDE GEGRÜNDET VON ERNST STEINKELLNER HERAUSGEGEBEN VON BIRGIT KELLNER, KLAUS-DIETER MATHES und MICHAEL TORSTEN MUCH HEFT 89 WIEN 2016 ARBEITSKREIS FÜR TIBETISCHE UND BUDDHISTISCHE STUDIEN UNIVERSITÄT WIEN Brandon Dotson and Agnieszka Helman-Ważny CODICOLOGY, PALEOGRAPHY, AND ORTHOGRAPHY OF EARLY TIBETAN DOCUMENTS METHODS AND A CASE STUDY WIEN 2016 ARBEITSKREIS FÜR TIBETISCHE UND BUDDHISTISCHE STUDIEN UNIVERSITÄT WIEN Herausgeberbeirat / Editorial Board Jens-Uwe Hartmann, Leonard van der Kuijp, Charles Ramble, Alexander von Rospatt, Cristina Scherrer-Schaub, Jonathan Silk, Ernst Steinkellner, Tom Tillemans Copyright © 2016 by Arbeitskreis für Tibetische und Buddhistische Studien / B. Dotson & A. Helman-Ważny ISBN: 978-3-902501-27-1 IMPRESSUM Verleger: Arbeitskreis für Tibetische und Buddhistische Studien Universitätscampus, Spitalgasse 2-4, Hof 2, 1090 Wien Herausgeber und für den Inhalt verantwortlich: B. Kellner, K.-D. Mathes, M. T. W. Much alle: Spitalgasse 2-4, Hof 2, 1090 Wien Druck: Ferdinand Berger und Söhne GmbH, Wiener Straße 80, 3580 Horn CONTENTS List of Illustrations . 7 Acknowledgements . 15 Introduction . 17 Methods . 33 Part One: Codicology . 33 Part Two: Orthography . 72 Part Three: Paleography . 91 Part Four: Miscellanea . 117 Case Study . 119 The Documents in Our Case Study . 122 Comparative Table . 143 Comparison . 162 Conclusions . 171 Appendix: Detailed Description of PT 1287 . 175 References . 197 Index . 209 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS FIGS. 1A–B: Large and small format pothī: S P1 folio from PT 1300, and “Chronicle Fragment” ITJ 1375; copyright Bibliothèque nationale de France and British Library . -

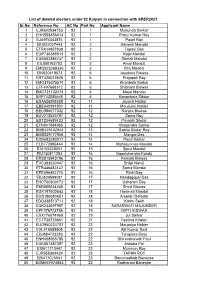

Sr.No Reference No AC No Part No Applicant Name 1 EJR602534753

List of deleted electors under 92 Kalyani in connection with SRER2021 Sr.No Reference No AC No Part No Applicant Name 1 EJR602534753 92 1 Mukunda Sarkar 2 EHH558456014 92 1 Pratul Kumar Roy 3 EJA974343874 92 1 Payel Roy 4 EIU002027443 92 2 Ganesh Mandal 5 ETR614857838 92 2 Tapasi Das 6 EGP736388513 92 2 Kajal Mandal 7 EUB502386747 92 2 Shefali Mandal 8 EIL050163793 92 2 Amal Mandal 9 EMQ923268336 92 2 Rita Mondal 10 EIN820419573 92 6 Joyatsna Biswas 11 ERT425012526 92 6 Prajapati Roy 12 EMO375375574 92 6 Kiranbala Sarkar 13 EFF497668312 92 6 Shibnath Biswas 14 EMC721102474 92 6 Maya Mondal 15 EYF742085668 92 6 Kananbala Sikdar 16 ESA626393528 92 11 Jayanti Haldar 17 EBE640991801 92 11 Mousumi Halder 18 EEU986577332 92 12 Ranjita Biswas 19 EUV212535787 92 12 Soma Roy 20 EST234689433 92 12 Priyashi Sikdar 21 EFN841884965 92 12 Khagendra Sarkar 22 EME449402944 92 13 Sabita Sikdar Roy 23 EMS829177866 92 14 Mangal Das 24 ECN693282011 92 14 Parul Sarkar 25 ELB772896444 92 14 Maharunnisa Mandal 26 EAI105328251 92 15 Sipra Mandal 27 EIU150811283 92 16 Gopalchandra Kundu 28 ERS815943196 92 16 Kamala Biswas 29 EVC383532447 92 16 Shilpi Nandi 30 ETR446483147 92 16 Soma Mondal 31 EPE596482775 92 16 Rinki Bag 32 EBJ839599081 92 17 Nandagopal Das 33 EHC700803173 92 17 Usharani Dey 34 EKB685034245 92 17 Shiuli Biswas 35 EGK197602643 92 18 Harimati Mondal 36 EGS186680651 92 18 Ameran Dafadar 37 EDQ338513711 92 18 Karim Sekh 38 EUK233697997 92 18 SARASWATI MAJUMDER 39 EPF076723786 92 19 DIPTI BISWAS 40 EXX176074968 92 19 Jui Sarkar 41 ECT730729861 92 -

Bu Ston-Van Der Kuijp

Some Remarks on the Textual Transmission and Text of Bu ston Rin chen grub's Chos 'byung, a Chronicle of Buddhism in India and Tibet* Leonard W.J. van der Kuijp Center for Tibetan Studies, Sichuan University Harvard University For János, wherever he may now be. he Chos 'byung or the Origin of the [Buddhist] Dharma, the now famous chronicle of Indo-Tibetan Buddhism that Bu T ston Rin chen grub (1290-1364) authored sometime between 1322 and 1326, has been known to non-Tibetan Indo- and Buddho- logical scholarship for over a century.1 Because of its author's con- summate command of the Tibetan Buddhist canonical literature and his numerous citations therefrom, this long treatise has played a sig- nificant, albeit a not always sufficiently appreciated, role in our un- derstanding of how Buddhism developed in the Indian subcontinent and in his native Tibet. Of course, one of the main reasons for its in- * Manuscripts listed under C.P.N. catalog numbers refer to those that I was happi- ly able to inspect, now two decades ago, in the Nationalities Library of the C[ultural] P[alace of] N[ationalities] in Beijing, and of which I was most of the time able to make copies. My translations sometimes include additional infor- mation that I believe is implicitly embedded in the original Tibetan text. Howev- er, I have dispensed with signaling most of these in square brackets for optical and aesthetic reasons. But anyone familiar with Tibetan will no doubt be able to recognize where I did add to the Tibetan text and be able to judge for him or her- self whether these extras are on target or outright misleading. -

Guntram Hazod Introduction1 Hapter Two of the Old Tibetan Chronicle (PT 1287: L.63-117; Hereafter OTC.2)

THE GRAVES OF THE CHIEF MINISTERS OF THE TIBETAN EMPIRE MAPPING CHAPTER TWO OF THE OLD TIBETAN CHRONICLE IN THE LIGHT OF THE EVIDENCE OF THE TIBETAN TUMULUS TRADITION Guntram Hazod Introduction1 hapter two of the Old Tibetan Chronicle (PT 1287: l.63-117; hereafter OTC.2)2 is well known as the short paragraph that C lists the succession of Tibet’s chief ministers (blon che, blon chen [po]) – alternatively rendered as “prime minister” or “grand chancel- lor” in the English literature. Altogether 38 such appointments among nineteen families are recorded from the time of the Yar lung king called Lde Pru bo Gnam gzhung rtsan until the end of the Tibet- an empire in the mid-ninth century. This sequence is conveyed in a continuum that does not distin- guish between the developments before and after the founding of the empire. Only indirectly is there a line that specifies the first twelve ministers as a separate group – as those who were endowed with 1 The resarch for this chapter was conducted within the framework of the two projects “The Burial Mounds of Central Tibet“, parts I and II (financed by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF); FWF P 25066, P 30393; see fn. 2) and “Materiality and Material Culture in Tibet“ (Austrian Academy of Sciences (AAS) project, IF_2015_28) – both based at the Institute for Social Anthropology at the Austrian Academy of Sciences. I wish to thank Joanna Bialek, Per K. Sørensen, and Chris- tian Jahoda for their valuable comments on the drafts of this paper, and J. Bialek especially for her assistance with lingustic issues. -

Mahabharata, Ramayana, Sita, Draupadi, Gandhari

Education 2014, 4(5): 122-125 DOI: 10.5923/j.edu.20140405.03 Sita (Character from the Indian epic –Ramayana), Draupadi and Gandhari (Characters from another Indian epic – Mahabharata) - A Comparative Study among Three Major Mythological Female Characters - Gandhari: An exception- Uditi Das1,*, Shamsad Begum Chowdhury1, Meejanur Rahman Miju2 1Institute of Education, Research and Training, University of Chittagong, Chittagong, Bangladesh 2Institute of Education, Research and Training (IERT), University of Chittagong, Chittagong, Bangladesh Abstract There are lots of female characters in Mahabharata and Ramayana but few characters enchant people of all ages and all classes. Mass people admit that Sita should be the icon of all women. Draupadi though a graceful character yet not to be imitated. Comparatively, Gandhari’s entrance into the epic is for a short while; though her appearance is very negligible, yet our research work is to show logically that Gandhari among these three characters is greater than the greatest. We think and have wanted to prove that Gandhari with her short appearance in the epic, excels all other female characters- depicted in Mahabharata and Ramayana. Keywords Mahabharata, Ramayana, Sita, Draupadi, Gandhari eighteen chapters. Again these chapters have been divided 1 . Introduction into one hundred sub-chapters. There are one lac (hundred thousand) verses in Mahabharata. Pandu, Kunti, Draupadi Ramayana: Ramayana is an epic composed by Valmiki and her five husbands, Dhritarastra, Gandhari and their one based on the life history of Ram-the king of the then Oudh hundred tyrannic sons – all are some of the famous and and is divided into seven cantos (Kanda). Sita was Ram’s notorious characters from this great epic.