Challenge Hypothesis’’

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Evolution of Cooperative Breeding in the African Cichlid Fish, Neolamprologus Pulcher

Biol. Rev. (2011), 86, pp. 511–530. 511 doi: 10.1111/j.1469-185X.2010.00158.x The evolution of cooperative breeding in the African cichlid fish, Neolamprologus pulcher Marian Wong∗ and Sigal Balshine Department of Psychology, Neuroscience & Behaviour, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, L8S 4L8, Canada (Received 14 December 2009; revised 5 August 2010; accepted 16 August 2010) ABSTRACT The conundrum of why subordinate individuals assist dominants at the expense of their own direct reproduction has received much theoretical and empirical attention over the last 50 years. During this time, birds and mammals have taken centre stage as model vertebrate systems for exploring why helpers help. However, fish have great potential for enhancing our understanding of the generality and adaptiveness of helping behaviour because of the ease with which they can be experimentally manipulated under controlled laboratory and field conditions. In particular, the freshwater African cichlid, Neolamprologus pulcher, has emerged as a promising model species for investigating the evolution of cooperative breeding, with 64 papers published on this species over the past 27 years. Here we clarify current knowledge pertaining to the costs and benefits of helping in N. pulcher by critically assessing the existing empirical evidence. We then provide a comprehensive examination of the evidence pertaining to four key hypotheses for why helpers might help: (1) kin selection; (2) pay-to-stay; (3) signals of prestige; and (4) group augmentation. For each hypothesis, we outline the underlying theory, address the appropriateness of N. pulcher as a model species and describe the key predictions and associated empirical tests. For N. -

Leary, C.J. 2014. Close-Range Vocal Signals Elicit a Stress Response in Male Green Treefrogs

Animal Behaviour 96 (2014) 39e48 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Animal Behaviour journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/anbehav Close-range vocal signals elicit a stress response in male green treefrogs: resolution of an androgen-based conflict * Christopher J. Leary Department of Biology, The University of Mississippi, Oxford, MS, U.S.A. article info Male courtship signals often stimulate the production of sex steroids in both female and male receivers. fi Article history: Such effects bene t signallers by increasing receptivity in females, but impose costs on signallers by Received 11 March 2014 promoting sexual behaviour and aggression in male competitors. To resolve this androgen-based conflict, Initial acceptance 24 April 2014 males should use strategies that suppress sex steroid production in rival males. In green treefrogs, Hyla Final acceptance 7 July 2014 cinerea, chorus sounds (i.e. advertisement calls from aggregates of males) are known to stimulate Published online 17 August 2014 androgen production in receiver males. Here, I examined whether males of this species counter these MS. number: A14-00205R effects by eliciting an endocrine stress response in male conspecifics during close-range vocal in- teractions. I show that corticosterone (CORT) levels were higher in males that lost vocal contests in Keywords: natural choruses compared to contest winners and nonaggressive males. Testosterone levels were also acoustic signal lower in contest losers compared to nonaggressive males, but not contest winners; dihydrotesterone challenge hypothesis levels did not differ among the three groups. Aggressive and advertisement calls were then broadcast to courtship signal glucocorticoid males in an experiment that simulated close-range vocal communication. -

Concepts Derived from the Challenge Hypothesis T ⁎ John C

Hormones and Behavior 115 (2019) 104550 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Hormones and Behavior journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/yhbeh Review article Concepts derived from the Challenge Hypothesis T ⁎ John C. Wingfielda, , Wolfgang Goymannb, Cecilia Jalabertc,d, Kiran K. Somac,d,e a Department of Neurobiology, Physiology and Behavior, University of California, One Shields Avenue, Davis, CA 95616, USA b Department of Behavioral Neurobiology, Max Planck Institute for Ornithology, Seewiesen, Germany c Department of Zoology, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada d Djavad Mofawaghian Centre for Brain Health, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada e Department of Psychology, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: The Challenge Hypothesis was developed to explain why and how regulatory mechanisms underlying patterns of State levels testosterone secretion vary so much across species and populations as well as among and within individuals. The Neurosteroids hypothesis has been tested many times over the past 30 years in all vertebrate groups as well as some in- Songbird vertebrates. Some experimental tests supported the hypothesis but many did not. However, the emerging con- Aggression cepts and methods extend and widen the Challenge Hypothesis to potentially all endocrine systems, and not only Testosterone control of secretion, but also transport mechanisms and how target cells are able to adjust their responsiveness to Mass spectrometry Androgens circulating levels of hormones independently of other tissues. The latter concept may be particularly important in explaining how tissues respond differently to the same hormone concentration. Responsiveness of the hy- pothalamo-pituitary-gonad (HPG) axis to environmental and social cues regulating reproductive functions may all be driven by gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) or gonadotropin-inhibiting hormone (GnIH), but the question remains as to how different contexts and social interactions result in stimulation of GnRH or GnIH release. -

UC Santa Barbara Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Santa Barbara UC Santa Barbara Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title How Collective Personality, Behavioral Plasticity, Information, and Fear Shape Collective Hunting in a Spider Society Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4pm302q6 Author Wright, Colin Morgan Publication Date 2018 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara How Collective Personality, Behavioral Plasticity, Information, and Fear Shape Collective Hunting in a Spider Society A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Ecology, Evolution and Marine Biology by Colin M. Wright Committee in charge: Professor Jonathan Pruitt, Chair Professor Erika Eliason Professor Thomas Turner June 2018 The dissertation of Colin M. Wright is approved. ____________________________________________ Erika Eliason ____________________________________________ Thomas Turner ____________________________________________ Jonathan Pruitt, Committee Chair April 2018 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my Ph.D. advisor, Dr. Jonathan Pruitt, for supporting me and my research over the last 5 years. I could not imagine having a better, or more entertaining, mentor. I am very thankful to have had his unwavering support through academic as well as personal challenges. I am also extremely thankful for all the members of the Pruitt Lab (Nick Keiser, James Lichtenstein, and Andreas Modlmeier), as well as my cohorts at both the University of Pittsburgh and UCSB that have been my closest friends during graduate school. I appreciate Dr. Walter Carson at the University of Pittsburgh for being an unofficial second mentor to me during my time there. Most importantly, I would like to thank my family, Rill (mother), Tom (father), and Will (brother) Wright. -

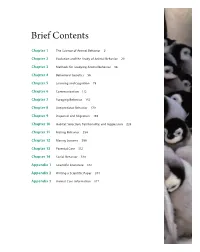

Brief Contents

B r i e f C o n t e n t s Chapter 1 The Science of Animal Behavior 2 Chapter 2 Evolution and the Study of Animal Behavior 20 Chapter 3 Methods for Studying Animal Behavior 38 Chapter 4 Behavioral Genetics 56 Chapter 5 Learning and Cognition 78 Chapter 6 Communication 112 Chapter 7 Foraging Behavior 142 Chapter 8 Antipredator Behavior 170 Chapter 9 Dispersal and Migration 196 Chapter 10 Habitat Selection, Territoriality, and Aggression 226 Chapter 11 Mating Behavior 254 Chapter 12 Mating Systems 286 Chapter 13 Parental Care 312 Chapter 14 Social Behavior 338 A p p e n d i x 1 Scientific Literature 372 Appendix 2 Writing a Scientific Paper 374 Appendix 3 Animal Care Information 377 C o n t e n t s P r e f a c e x x i i i Chapter 1 The Science of Animal Behavior 2 1.1 Animals and their behavior are an integral part of human society 4 Recognizing and defi ning behavior 5 Measuring behavior: elephant ethograms 5 1.2 Th e scientifi c method is a formalized way of knowing about the natural world 6 Th e importance of hypotheses 7 Th e scientifi c method 7 Correlation and causality 10 Hypotheses and theories 11 Social sciences and the natural sciences 11 1.3 Animal behavior scientists test hypotheses to answer research questions about behavior 12 Hypothesis testing in wolf spiders 12 Negative results and directional hypotheses 13 Generating hypoth eses 14 Hypotheses from mathematical models 14 1.4 Anthropomorphic explanations of behavior assign human emotions to animals and can be diffi cult to test 15 1.5 Scientifi c knowledge is generated and -

Hormonal Anticipation of Territorial Challenges in Cichlid Fish

Hormonal anticipation of territorial challenges in cichlid fish Raquel A. Antunesa,b and Rui F. Oliveiraa,b,1 aUnidade de Investigac¸a˜ o em Eco-Etologia, Instituto Superior de Psicologia, Aplicada, Rua Jardim do Tabaco 34, 1149-041 Lisboa, Portugal; and bChampalimaud Neuroscience Programme, Instituto Gulbenkian de Cieˆncia, Rua da Quinta Grande 6, 2780-156 Oeiras, Portugal Edited by Edward A. Kravitz, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, and approved July 22, 2009 (received for review January 23, 2009) In many territorial species androgens respond to social interac- individuals take part influences their androgen levels and an- tions. This response has been interpreted as a mechanism for drogens will themselves modulate perceptual, motivational, or adjusting aggressive motivation to a changing social environment. cognitive mechanisms that influence behavior (2, 11), therefore Therefore, it would be adaptive to anticipate social challenges and optimizing behavioral performance in future social interactions. reacting to their clues with an anticipatory androgen response to It would thus be adaptive for the individuals to predict social adjust agonistic motivation to an imminent social challenge. Here challenges and to respond to their clues with an anticipatory we test the hypothesis of an anticipatory androgen response to increase in androgen levels. Even though the conditioned release territorial intrusions using classical conditioning to establish an of androgens has already been shown after conditioning of light) and an mating behavior -

CAVEMAN ECONOMICS Towards a Biological Synthesis Of

CAVEMAN ECONOMICS Towards a Biological Synthesis of Neoclassical and Behavioral Economics. © Terence C. Burnham October 2011 Abstract There is a schism within economics between the neoclassical view that people optimize and the behavioral view that people are filled with biases and heuristics. In recent decades, the behavioral school has been on the ascent. A primary cause of the behavioral ascent is the experimental evidence of deviations between actual behavior and the neoclassical prediction of behavior. While behavioral scholars have documented these “anomalies,” they have made little progress explaining the origin of such behavior. This paper proposes a biological and evolutionary foundation for the anomalies of behavioral economics by separating proximate and ultimate causation. Such a foundation may allow for a re-uniting of economics; a neo-Darwinian synthesis of neoclassical and behavioral economics. Introduction Economics is divided into two competing schools based on divergent views of human nature. Neoclassical economists assume that people make optimal decisions. In sharp contrast, behavioral economists believe that people make systematic mistakes. Behavioral economics has made significant advances in recent decades. At the core of these behavioral successes is the empirical evidence of divergences between neoclassical predictions of human behavior and actual human behavior. Richard Thaler calls these divergences “anomalies.” Neoclassical economics is unique among the social sciences in deriving conclusions from a small number of underlying axioms. However, each and every neoclassical axiom now has a behavioral economic literature that documents related anomalies. Neoclassical economists dismiss the behavioral anomalies as interesting quirks, laboratory artifacts, or small-stakes effects that can be ignored when working on important issues. -

Mating Systems in Cooperative Breeders : the Roles of Resource Dispersion and Conflict Mitigation

Erschienen in: Behavioral Ecology ; 23 (2012), 3. - S. 521-530 https://dx.doi.org/10.1093/beheco/arr218 Mating systems in cooperative breeders: the roles of resource dispersion and conflict mitigation M. Y. L. Wong,a L. A. Jordan,b S. Marsh-Rollo,c S. St-Cyr,d J. O. Reynolds,e K. A. Stiver,f J. K. Desjardins,g J. L. Fitzpatrick,h and S. Balshinec aDepartment of Biology, Boston University, 5 Cummington Street, Boston, MA 02215, USA, bSchool of Biological, Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of New South Wales, Sydney, New South Wales 2052, Australia, cDepartment of Psychology, Neuroscience and Behaviour, McMaster University, 1280 Main Street West, Hamilton, Ontario L8S 4K1, Canada, dDepartment of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Toronto, 25 Willcocks Street, Ontario M5S 3B2, Canada, eVancouver Aquarium, 845 Avison Way, Vancouver, British Columbia V6G 3E2, Canada, fDepartment of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, Yale University, 165 Prospect Street, New Haven, CT 06520, USA, gDepartment of Biology, Stanford University, Stanford, Gilbert Hall, CA 94305, USA, and hCentre for Evolutionary Biology, University of Western Australia, 35 Stirling Highway, Crawley, Western Australia 6009, Australia Within animal societies, the ecological and social underpinnings of mating system variation can be related to resource dispersion, sexual conflict between breeders, and the effects of non breeders. Here, we conducted a broad scale investigation into the evolution of mating systems in the cooperatively breeding cichlid, Neolamprologus pulcher, a species that exhibits both monogamy and polygyny within populations. Using long term field data, we showed that polygynous groups were more spatially clustered and held by larger competitively superior males than were monogamous groups, supporting the role of resource dispersion. -

The Challenge Hypothesis in an Insect: Juvenile Hormone Increases During Reproductive Conflict Following Queen Loss in Polistes Wasps

vol. 176, no. 2 the american naturalist august 2010 The Challenge Hypothesis in an Insect: Juvenile Hormone Increases during Reproductive Conflict following Queen Loss in Polistes Wasps Elizabeth A. Tibbetts1,* and Zachary Y. Huang2 1. Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109; 2. Department of Entomology, Ecology, Evolutionary Biology and Behavior, Michigan State University, East Lansing, Michigan 48824 Submitted November 10, 2009; Accepted March 31, 2010; Electronically published June 1, 2010 within wild populations (Ketterson et al. 1996; Ball and abstract: The challenge hypothesis was proposed as a mechanism Balthazart 2008). for vertebrates to optimize their testosterone titers by upregulating testosterone during periods of aggressive competition. Here we test In vertebrates, much research on the context depen- key predictions of the challenge hypothesis in an independently dence of hormonal actions has focused on social modu- evolved endocrine system: juvenile hormone (JH) in a social insect. lation of the steroid hormone testosterone (T). T is often We assess how social conflict influences JH titers in Polistes dominulus associated with benefits such as increased competitiveness, wasps. Aggressive conflict was produced by removing the queen from fertility, and mating success, but high T titers are also some colonies (experimental) and a low-ranked worker from other associated with costs such as reduced immune function colonies (control). Queen removal produced competition among and survival (Wingfield et al. 2001; Adkins-Regan 2005). workers to fill the reproductive vacancy. Workers upregulated their JH titers in response to this social conflict; worker JH titers were Individuals are hypothesized to mitigate these trade-offs higher in queenless than in queenright colonies. -

The SAGE Encyclopedia of War: Social Science Perspectives Competition

The SAGE Encyclopedia of War: Social Science Perspectives Competition Contributors: Francis T. McAndrew Edited by: Paul Joseph Book Title: The SAGE Encyclopedia of War: Social Science Perspectives Chapter Title: "Competition" Pub. Date: 2017 Access Date: October 14, 2016 Publishing Company: SAGE Publications, Inc. City: Thousand Oaks, Print ISBN: 9781483359892 Online ISBN: 9781483359878 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781483359878.n149 Print pages: 367-368 ©2017 SAGE Publications, Inc.. All Rights Reserved. This PDF has been generated from SAGE Knowledge. Please note that the pagination of the online version will vary from the pagination of the print book. SAGE SAGE Reference Contact SAGE Publications at http://www.sagepub.com. War is a male activity. Organized fighting and killing by groups of women against other groups of women has simply not existed at any point in human history, and given the wide range of diversity to be found across human cultures, the consistency with which males are the organizers and perpetrators of group conflict has led many scholars to conclude that the male propensity for group violence is rooted in more than the learning of culturally prescribed gender roles. Evolutionary psychologists have studied war and conflict with the assumption that a predisposition for warfare has evolved in males because it has historically (and prehistorically) enhanced their reproductive success. Hence, the origins of warfare can ultimately be found in the competition between males for status and access to mates. Male Competition and Violence The adaptive problems faced by men and women throughout history were quite different, and aggression proved to be a more adaptive response for males than for females. -

Author's Personal Copy

Hormones and Behavior 51 (2007) 461–462 www.elsevier.com/locate/yhbeh Commentary Advancing the Challenge Hypothesis Ignacio T. Moore Department of Biological Sciences, 2119 Derring Hall, Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, VA 24061, USA Received 1 February 2007; revised 16 February 2007; accepted 23 February 2007 Available online 2 March 2007 The Challenge Hypothesis has been a cornerstone of the hypothesis with some variation based on taxa (Hirschen- behavioral endocrinology since it was first proposed (Wingfield hauser and Oliveira, 2006). These two studies were significant et al., 1990). This hypothesis originally sought to explain the advances in our understanding of how androgen patterns vary complex seasonal patterns of androgens in birds. While there is with life history. As more species are tested, across broader a basic pattern of males having higher androgen levels during taxonomic groups, these analyses will need to be repeated. the breeding season than non-breeding season, males of many The study by Goymann, Landys and Wingfield (current species also exhibit different baseline androgen levels during issue) is another significant advance in the Challenge Hypoth- different breeding sub-stages and spikes in androgen levels esis. Prior to this study, investigators have not always attempted associated with either social instability or female receptiveness. to discriminate the causes of the increase in androgens above By investigating the social mating system, the degree of male– breeding baseline levels (defined as level B in the paper). The male aggression, and the degree of paternal care, Wingfield and assumption was generally made that these high levels (defined colleagues developed predictions about how androgen levels as level C in the paper) were the result of social interactions, should vary seasonally. -

The Challenge Hypothesis Revisited Focus on Reproductive Experience and Neural Mechanisms

UC Davis UC Davis Previously Published Works Title The challenge hypothesis revisited: Focus on reproductive experience and neural mechanisms. Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8m77f0qx Authors Marler, Catherine A Trainor, Brian C Publication Date 2020-07-01 DOI 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2019.104645 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Hormones and Behavior xxx (xxxx) xxxx Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Hormones and Behavior journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/yhbeh Review article The challenge hypothesis revisited: Focus on reproductive experience and neural mechanisms ⁎ Catherine A. Marlera, , Brian C. Trainorb a Department of Psychology, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI 53706, USA b Department of Psychology, University of California, Davis, CA 95616, USA ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Our review focuses on findings from mammals as part of a Special Issue “30th Anniversary of the Challenge Vigilance Hypothesis”. Here we put forth an integration of the mechanisms through which testosterone controls territorial Androgens behavior and consider how reproductive experience may alter these mechanisms. The emphasis is placed on the Hippocampus function of socially induced increases in testosterone (T) pulses, which occur in response to social interactions, as Bed nucleus of the stria terminalis elegantly developed by Wingfield and colleagues. We focus on findings from the monogamous California mouse, Conditioned place preference as data from this species shows that reproductive status is a key factor influencing social interactions, site Challenge hypothesis fi ff fi ff Rapid effects delity, and vigilance for o spring defense. Speci cally, we examine di erences in T pulses in sexually naïve Nucleus accumbens versus sexually experienced pair bonded males.