Orissa State Case Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Analysis of Trade and Commerce in the Princely States of Nayagarh District (1858-1947)

Odisha Review April - 2015 An Analysis of Trade and Commerce in the Princely States of Nayagarh District (1858-1947) Dr. Saroj Kumar Panda The present Nayagarh District consists of Ex- had taken rapid strides. Formerly the outsiders princely states of Daspalla, Khandapara, only carried on trade here. But of late, some of Nayagarh and Ranpur. The chief occupation of the residents had turned traders. During the rains the people of these states was agriculture. When and winter, the export and import trade was the earnings of a person was inadequate to carried on by country boats through the river support his family, he turned to trade to Mahanadi which commercially connected the supplement his income. Trade and commerce state with the British districts, especially with attracted only a few thousand persons of the Cuttack and Puri. But in summer the trade was Garjat states of Nayagarh, Khandapara, Daspalla carried out by bullock carts through Cuttack- and Ranpur. On the other hand, trade and Sonepur Road and Jatni-Nayagarh-Daspalla commerce owing to miserable condition of Road. communications and transportations were of no importance for a long time. Development of Rice, Kolthi, Bell–metal utensils, timbers, means of communication after 1880 stimulated Kamalagundi silk cloths, dying materials produced the trade and commerce of the states. from the Kamalagundi tree, bamboo, mustard, til, molasses, myrobalan, nusevomica, hide, horns, The internal trade was carried on by means bones and a lot of minor forest produce, cotton, of pack bullocks, carts and country boats. The Mahua flower were the chief articles of which the external trade was carried on with Cuttack, Puri Daspalla State exported. -

Sri Sri Nilamadhava of Kantilo

Orissa Review June - 2009 Sri Sri Nilamadhava of Kantilo Geeta Devi Kantilo is a big village of the ex-state of 'Kanti' is a race name which still exists at Khandapara, situated on the south bank of the Kantilo. They were a trading class (Vaishya river Mahanadi and on the ancient route of Vanika) previously known as 'Sadhavas'. They Jagannath Sadak, which served as an important were entrusted with the duty of collecting taxes link between Cuttack and Sambalpur both on the from the navigators and traders passing through roadways and waterways. Kantilo on the river Mahanadi. They were also acting as official in charge of the Ghat. The race The very geographical situation for the place name 'Kanti' is derived from their official makes it a commercial centre for traders. Apart designation called 'Kanta Adhikari'. 'Kanta' refers from the trade goods like salt, spices, tabacco, to the instrument of measurement. The weighing cotton, oil seeds and molasses, Kantilo trades balance used by these Kanta Adhikaris was with brass and bell metal utensils which are its known as 'Kanti'. own native products. Molasses, a sugarcane product was usually Several theories have cropped up through exported from this 'ghat' to the hinterland. ages to justify the place name of Kantilo. The last Molasses was measured by 'Banas' (an earthern part of the word, 'Lo' may be a reduced form of container). A particular size of Bana was also the Sanskrit word 'Lava'. 'Lava' refers to low and called 'Kanti'. So both for the measurement of deep river bed which helps in navigation. -

Nayagarh District

Govt. of India MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD OF NAYAGARH DISTRICT South Eastern Region Bhubaneswar May , 2013 1 District at a glance SL. ITEMS STATISTICS NO 1. GENERAL INFORMATION a) Geographical area (Sq.Km) 3,890 b) Administrative Division Number of Tehsil/Block 4 Tehsils/8 Blocks Number of GramPanchayats(G.P)/villages 179 G.Ps, 1695 villages c) Population (As on 2011 census) 9,62,215 2. GEOMORPHOLOGY Major physiographic units Structural Hills, Denudational Hills, Residual Hills, Lateritic uplands, Alluvial plains, Intermontane Valleys Major Drainages The Mahanadi, Burtanga, Kaunria, Kamai & the Budha nadi 3. LAND USE (Sq. Km) a) Forest area: 2,080 b) Net area sown: 1,310 4. MAJOR SOIL TYPES Alfisols, Ultisols 5. IRRIGATION BY DIFFERENT SOURCES (Areas and number of structures) Dug wells 14707 dug wells with Tenda, 783 with pumps Tube wells/ Bore wells 16 shallow tube wells, 123 filter point tube well Gross irrigated area 505.7 Sq.Km 6. NUMBERS OF GROUND WATER 16 MONITORING WELLS OF CGWB (As on 31.3.2007) Number of Dug Wells 16 Number of Piezometers 5 7. PREDOMINANT GEOLOGICAL Precambrian: Granite Gneiss, FORMATIONS Khondalite, Charnockite Recent: Alluvium 9. HYDROGEOLOGY Major water bearing formation Consolidated &Unconsolidated formations Premonsoon depth to water level Min- 0.65 (Daspalla- I) during 2006(mbgl) Max- 9.48 (Khandapada)& Avg. 4.92l 2 Min –0.17 (Nayagarh), Post-monsoon Depth to water level Max- 6.27 (Daspalla-II) & during 2006(mbgl) Avg.- 2.72 8 number of NHS shows Long term water level trend in 10 yrs rising trend from 0.027m/yr to (1997-2007) in m/yr 0.199m/yr & 8 show falling trend from 0.006 to 0.106m/yr. -

STATE LEVEL EXPERT APPRAISAL COMMITTEE, ODISHA (Constituted Vide Order No

ANNEXURE – A STATE LEVEL EXPERT APPRAISAL COMMITTEE, ODISHA (Constituted vide order No. S.O. 1217 (E) dated 08th March 2019 of MoEF&CC, Govt. of India) Paribesh Bhawan, A/118, Nilakantha Nagar, Unit –VIII, Bhubaneswar – 751 012, Odisha DATE & TIME : 03RD June 2020 AT 03:00 PM VENUE : Conference Hall of State Pollution Control Board, A/118, Nilakantha Nagar, Unit –VIII, Bhubaneswar – 12 MEETING OF THE STATE LEVEL EXPERT APPRAISAL COMMITTEE, ODISHA AGENDA I. CONSIDERATION OF MINOR MINERAL PROPOSALS (15 Nos.): Sl. File No. Proposal No. 1. SEIAA- Proposal for Environmental Clearance for Kurula Brick Earth Quarry over an 69/02-2020 area of 2.224 acres or 0.900 ha. in village Kurula, Tahasil Sheragada in the district of Ganjam of Sri Kalu Charan Nayak (EC) 2. SEIAA- Proposal for Environmental Clearance for Kurula Brick Earth Quarry over an 70/02-2020 area of 2.824 acres or 1.143 ha. in village Kurula, Tahasil Sheragada in the district of Ganjam of Sri K. Damodar Patra, (EC) 3. SEIAA- Proposal for Environmental Clearance for Tumbakana Stone Quarry over 74/02-2020 an area of 2.00 acres or 0.809 ha. at village Tumbakana Tahasil Ramanguda in the district of Rayagada of Sri Chandrasekhar Panigrahi (EC) 4. SEIAA- Proposal for Environmental Clearance for Jhoridi Stone Quarry over an 75/02-2020 area of 3.00 acres or 1.214 ha. at village Jhoridi Tahasil Kolnara in the district of Rayagada of Sri Ganesh Prasad Chaurasia (EC) 5. SEIAA- Proposal for Environmental Clearance for Changuapada Sand Quarry over 76/03-2020 an area of 8.00 acres or 3.237 ha. -

Itamati-752068 M 2 OD51386 Nayagarh SL Anchalika

Sl. Alphanumeric District Name and address of Unit Name of the P.O.& Date of P.O.Mobile Training No. Code College and School Category Department. appointment. No. Status alongwith name of Dist. And Pin Code No. 1 OD51385 Nayagarh Itamati College of M Sri Avimanyu Sahoo, 01.06.10 9437629325 Trained Education & Lect. in Pol.Science Technology, At/Po: Itamati-752068 2 OD51386 Nayagarh S. L. Anchalika M Sri Santosh Kumar 01.07.10 9438036600 Trained College, Sahoo, At/Po:Godipada, Lect. in Sanskrit, P.S:Sarankul 3 OD51387 Nayagarh K.P.D. Women’s F Rajalaxmi Sahoo, 01.01.11 9658433591 Trained College, Daspala, Lect. in Edn At/Po:Daspalla-752084 4 OD51388 Nayagarh Nuagaon M Sri Maheswar Pradhan, 01.07.07 9437828170 Trained Mahavidyalaya, Lect. in Eng Nuagaon, At/Po:Nuagaon,- 752083 5 OD51389 Nayagarh Prahallad M Sri Janmejaya Nayak. 13.03.10 9437517251 Trained Mahavidyalaya, Lect. in History Padmabati, At/Po:Padmabati, Tikiripada-752053, Via: Bhapur 6 OD51390 Nayagarh Prahallad F Purnima Sarangi, 01.12.10 9438133552 Trained Mahavidyalaya, Lect. in Commerce Padmabati, At/Po:Padmabati, Tikiripada-752053,Via: Bhapur 7 OD51391 Nayagarh Sri Sri Raghunath Jew M Sri Purna Chandra 01.04.10 9778074405 Untrained Mahavidyalaya, Nayak, Gania,At/Po:Gania,- Lect. in Odia 752085 8 OD51392 Nayagarh Ananda Sahoo F Ms. Nalini Prabha 01.05.11 8895492374 Trained Women’s College, Bhola. Komanda, Lect. in Economics At/Po:Komanda- 752090 9 OD51393 Nayagarh Gorhbanikilo College, M Sri Rajanikanta Sethi, 01.09.11 9178762926 Trained Gorhbanikilo, Lect. in English At/Po:Gorhbanikilo 10 OD51394 Nayagarh Maa Maninag Durga M Kanaklata Swain, 01.05.10 9937187290 Trained Mahila Mahavidyalaya, Lect. -

Class: +3 Final Year Sixth Semester Consolidated Data Format for Online

Consolidated data Format for online Examination-2021 Student data base subject wise College/Institution: Nayagarh Prajamandal Mahila Mahavidyalaya, Nayagarh Subject : Economics Name of the Mentor : Mrs. Binodini Narendra, H.O.D., Economics Class: +3 Final Year Sixth Semester WhatsApp WhatsApp no. & Sl. Student Name Category(SC/ST/P Current no. & Alt. Alt. Mob.No. of E mail ID of the student/ Univ. Roll No Regd. No Domicile Permanent Address No. (in Capital) wD) Address Mob.No. of Guardian/ Alt. Mail Id (if available) student Parents At- Paika Bankatara P.O.- Kuruma ADYASHA 1 12N0118001 UG-4335/2018 ODISHA Bankatara Same 9556775823 [email protected] MAHAPATRA Dist.- Nayagarh Pin- 752081 At- Gholahandi P.O.- Gobindapurpatana, 2 12N0118002 UG-4336/2018 AMISHA DASH ODISHA Same 9438506640 [email protected] Dasapalla Dist.- Nayagarh Pin- 752093 C/O- Sarat Chandra Sethi At- Krushnachandrapur Patana 3 12N0118003 UG-4337/2018 ARPITA SETHI SC ODISHA Same 8984080284 [email protected] P.O.- Satapatana, Dasapalla Dist.- Nayagarh Pin- At- Pathuria sahi, BARSA At/P.O.- Sarankul [email protected] 4 12N0118004 UG-4338/2018 PRIYADARSINI ODISHA Same 7077743293 Dist.- Nayagarh rudraparida@adityabirla PARIDA Pin- 752080 D/O- Biranchi Narayan Sahoo At- Ratnapurpatana 5 12N0118005 UG-4339/2018 BARSARANI SAHOO ODISHA Same 7978252263 [email protected] P.O.- Itamati Dist.- Nayagarh Pin- 752068 At- Tulasipur BARSHA P.O.- Ostia 6 12N0118006 UG-4340/2018 ODISHA Same 8114900905 [email protected] PRIYADARSHINI Dist.- -

The Orissa G a Z E T T E

Click Here & Upgrade Expanded Features PDF Unlimited Pages CompleteDocuments The Orissa G a z e t t e EXTRAORDINARY PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY No. 1861 CUTTACK, FRIDAY, DECEMBER 31, 2004 / PAUSA 10, 1926 No. 16623±FEII.-CR.-1/2004(Pt.) - W. GOVERNMENT OF ORISSA WORKS DEPARTMENT RESOLUTION The 22nd September 2004 Keeping in view of the newly created Districts, the proposal for reorganisation of (R. & B.) Divisions was under active consideration of Government for some time past. Taking into account of the necessity, workload and infrastructure available, Government have been pleased to decide for :² (i) Constitution of Nayagarh (R. & B.) Division (ii) Reorganisation of existing Khurda (R. & B.) Division (iii) Redistribution of work of the existing Bhubaneswar (R. & B.) Division Nos. I, II, III & IV Constitution of Nayagarh (R. & B.) Division (A) It is decided to constitute Nayagarh (R. & B.) Division with three Subdivisions and 9 Sections. The existing office of the Executive Engineer, Bhubaneswar (R. & B.) Division No. IV along with staff and assets are to be shifted to Nayagarh and function as office of the Executive Engineer, Nayagarh (R. & B.) Division . The existing Nayagarh (R. & B.) Subdivision and Dasapalla (R. & B.) Subdivision functioning as such under Khurda (R. & B.) Division shall be bodily transferred to the control of the newly constituted Nayagarh (R. & B.) Division. Further, Ranpur (R. & B.) Section under Khurda (R. & B.) Subdivision shall be transferred to the control of Nayagarh (R. & B.) Subdivision. Bhubaneswar (R. & B.) Subdivision No. XII with its Sections 34 & 35 along with its staff and assets shall be bodily shifted to the control of Nayagarh (R. -

Place Based Incentive.Pdf

GOVERNMENT OF ODISHA HEALTH & FAMILY WELFARE DEPARTMENT *** NOTIFICATION )c)5. 9 6 35/2015- /H., Dated: Government of Odisha is committed to provide adequate, acceptable, accessible, equitable and affordable Health Care Services to the people of Odisha. It has been experienced that retention of medical officers in rural and remote areas with specific focus on KBK, KBK+ and Tribal Sub-Plan areas continues to remain a big challenge before the Health Service sector. In order to incentivise the doctors to work in KBK, KBK+ and Tribal Sub-Plan difficult areas Government have been paying special incentive / allowance of Rs. 4,000/- per month to the M.Os. working at DHHs and SDHs and Rs. 8,000/- per month to the M.Os. working in CHCs and PHCs vide H & FW Department resolution No. 1489/H, dtd. 20.01.2012. However, it was seen that this needed a re-examination. It is therefore felt necessary to provide place based incentives to the Medical Officers working in different difficult / remote areas in the state as per vulnerability status of the places taking into consideration certain key parameters such as difficult and back wardness of the location, tribal dominance, left wing extremisms, train communication, road and transport facilities, social infrastructure and distance from state head quarter etc. Hence, Government have been pleased to categories the peripheral health institutions of the state as follows basing on their vulnerability status. 1. Vulnerability status of peripheral Health Institutions :- All the 1751 (One thousand seven hundred fifty one) peripheral Government Health Institutions of the State are differentiated into five different categories and declared as V-0 to V-4 Health Institutions as mentioned at Annexure-'A', taking into consideration their vulnerability status. -

Brief Industrial Profile of NAYAGARH District 2019-20

Government of India Ministry of MSME Brief Industrial Profile of NAYAGARH District 2019-20 Carried out by MSME - Development Institute, Cuttack (Ministry of MSME, Govt. of India,) (As per guidelines of O/O DC (MSME), New Delhi) Phone: 0671-2548049, 2548077 Fax: 0671-2548006 E. Mail:[email protected] Website: www.msmedicuttack.gov.in ii F O R E W O R D Every year Micro, Small & Medium Enterprises Development Institute, Cuttack under the Ministry of Micro, Small & Medium Enterprises, Government of India has been undertaking the Industrial Potentiality Survey for the districts in the state of Odisha and brings out the Survey Report as per the guidelines issued by the office of Development Commissioner (MSME), Ministry of MSME, Government of India, New Delhi. Under its Annual Action Plan 2019-20, all the districts of Odisha have been taken up for the survey. This Industrial Potentiality Survey Report of Nayagarh district covers various parameters like socio- economic indicators, present industrial structure of the district, and availability of industrial clusters, problems and prospects in the district for industrial development with special emphasis on scope for setting up of potential MSMEs. The report provides useful information and a detailed idea of the industrial potentialities of the district. I hope this Industrial Potentiality Survey Report would be an effective tool to the existing and prospective entrepreneurs, financial institutions and promotional agencies while planning for development of MSME sector in the district. I like to place on record my appreciation for Dr. Shibananda Nayak, AD(EI) of this Institute for his concerted efforts to prepare this report under the guidance of Dr. -

Automatically Generated PDF from Existing Images

VALID LIST OF CANDIDATES APPLIED FOR THE POST OF (B.A.B.Ed., LANGUAGE) SIKSHYA SAHAYAK OF NAYAGARH DISTRICT. Sl. Inde Name of the Candidates & Address Post Applied for Date of birth Adv. Date Age as on Employement Regd. Date of Sports / category Gender Marital Whether Whether OTET Qualification Total whether RCI One No. of self Two Self ID Proof NOC in Postal Satatus Remarks No. x 14.01.2019 No. valid/ Invalied Residential Ex- SC/ST Status submitte Trained or Pass Percentage certificate attested passport addressed case of any No. certificate service /SEBC d Untrained Certific submitted or size photograph envelope employees Issue. P.H. /women affdavit ate not. having postal HSC +2 +3 CT/BED or not stamp worth Total mark Percenta Total mark Percentage Total mark Percenta Total Mark Percent Rs.22/- each mark secured ge mark secured mark secure ge mark secur age. d ed 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 Sushree Suchismita Nayak, D/o-Upendra Kumar B.A.B.Ed. 1 139 Pradhan, At/Po-Nuagaon, Dist-Nayagarh, Pin- 18/04/1996 14-Jan-2019 22Y,8M,27D OD00120189089 22.08.2018 - SEBC F U Yes Trained Yes 600 528 88.00 800 680 85 2000 1643 82.150 255.150 - Yes Yes Yes - SP (Language) 752083 Runubala Jena D/o- Sanatan Jena B.A.B.Ed. OD001201711694/Oct- 2 333 At- Chandiprasad, Po- Gunthuni 16/05/1995 14-Jan-2019 23Y,7M,29D 14.10.2016 - SEBC F M Yes Trained Yes 600 507 84.50 800 619 77.375 1700 1366 80.353 242.227941 - Yes Yes Yes - SP (Language) 2020 Ps- Khandapada, Dist- Nayagarh, Pin- 752068 Sarat Kumar Sahoo, S/o- Jogendra Sahoo, AT- B.A.B.Ed. -

IND: Rural Connectivity Investment Program Odisha

Due Diligence Report on Social Safeguards July 2013 IND: Rural Connectivity Investment Program Odisha Prepared by Ministry of Rural Development, Government of India for the Asian Development Bank. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 12 August 2013) Currency unit – Indian Rupees (INR) INR1.00 = $ 0.01648 $1.00 = INR 60.6795 ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ADB : Asian Development Bank APs : Affected Persons BPL : Below Poverty Line CD : Cross Drainage DM : District Magistrate EA : Executing Agency EAF : Environment Assessment Framework ECOP : Environmental Codes of Practice FFA : Framework Financing Agreement GOI : Government of India GRC : Grievances Redressal Committee IA : Implementing Agency IEE : Initial Environmental Examination MFF : Multitranche Financing Facility MORD : Ministry of Rural Development MOU : Memorandum of Understanding NC : Not Connected NGO : Non-Government Organization NRRDA : National Rural Road Development Agency NREGP : National Rural Employment Guarantee Program OSRRA : Odisha State Rural Road Agency PIU : Project Implementation Unit PIC : Project Implementation Consultants PFR : Periodic Finance Request PMGSY : Pradhan Mantri Gram Sadak Yojana ROW : Right-of-Way RRP : Report and Recommendation of the President RRSIP II : Rural Roads Sector II Investment Program SRRDA : State Rural Road Development Agency ST : Scheduled Tribes TA : Technical Assistance TOR : Terms of Reference TSC : Technical Support Consultants UG : Upgradation WHH : Women Headed Households GLOSSARY Affected Persons (APs): Affected persons are people (households) who stand to lose, as a consequence of a project, all or part of their physical and non-physical assets, irrespective of legal or ownership titles. Encroacher: A person, who has trespassed government land, adjacent to his/her own land or asset, to which he/she is not entitled, by deriving his/her livelihood there. -

Nayagarh.Pdf

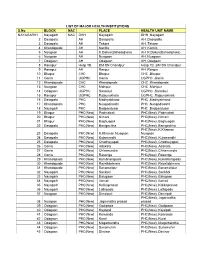

LIST OF MAJOR HEALTH INSTITUTIONS S.No BLOCK NAC PLACE HEALTH UNIT NAME NAYAGARH1 Nayagarh NAC DHH Nayagarh DHH ,Nayagarh 2 Dasapala AH Dasapalla AH ,Dasapalla 3 Dasapala AH Takara AH ,Takara 4 Khandapada AH Kantilo AH ,Kantilo 5 Nuagaon AH K.Dakua(Bahadajhola) AH ,K.Dakua(Bahadajhola) 6 Nuagaon AH Nuagaon AH ,Nuagaon 7 Odagaon AH Odagaon AH ,Odagaon 8 Ranapur Hosp TB BM SN Chandpur Hosp TB ,BM SN Chandpur 9 Ranapur AH Ranpur AH ,Ranpur 10 Bhapur CHC Bhapur CHC ,Bhapur 11 Gania UGPHC Gania UGPHC ,Gania 12 Khandapada CHC Khandapada CHC ,Khandapada 13 Nuagaon CHC Mahipur CHC ,Mahipur 14 Odagaon UGPHC Sarankul UGPHC ,Sarankul 15 Ranapur UGPHC Rajsunakhala UGPHC ,Rajsunakhala 16 Dasapala PHC Madhyakhand PHC ,Madhyakhand 17 Khandapada PHC Nuagadiasahi PHC ,Nuagadiasahi 18 Nayagarh PHC Badpandusar PHC ,Badpandusar 19 Bhapur PHC(New) Padmabati PHC(New) ,Padmabati 20 Bhapur PHC(New) Nimani PHC(New) ,Nimani 21 Bhapur PHC(New) Baghuapali PHC(New) ,Baghuapali 22 Dasapala PHC(New) Banigochha PHC(New) ,Banigochha PHC(New) ,K.Khaman 23 Dasapala PHC(New) K.Khaman Nuagaon Nuagaon 24 Dasapala PHC(New) Kujamendhi PHC(New) ,Kujamendhi 25 Dasapala PHC(New) Chadheyapali PHC(New) ,Chadheyapali 26 Gania PHC(New) Adakata PHC(New) ,Adakata 27 Gania PHC(New) Chhamundia PHC(New) ,Chhamundia 28 Gania PHC(New) Rasanga PHC(New) ,Rasanga 29 Khandapada PHC(New) Kumbharapada PHC(New) ,Kumbharapada 30 Khandapada PHC(New) Rayatidolmara PHC(New) ,Rayatidolmara 31 Khandapada PHC(New) Banamalipur PHC(New) ,Banamalipur 32 Nayagarh PHC(New) Sankhoi PHC(New) ,Sankhoi 33 Nayagarh