Public Health Action Screening Patients with Tuberculosis For

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Covid 19 Coastal Plan- Trivandrum

COVID-19 -COASTAL PLAN Management of COVID-19 in Coastal Zones of Trivandrum Department of Health and Family Welfare Government of Kerala July 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS THIRUVANANTHAPURAMBASIC FACTS .................................. 3 COVID-19 – WHERE THIRUVANANTHAPURAM STANDS (AS ON 16TH JULY 2020) ........................................................ 4 Ward-Wise maps ................................................................... 5 INTERVENTION PLANZONAL STRATEGIES ............................. 7 ANNEXURE 1HEALTH INFRASTRUCTURE - GOVT ................. 20 ANNEXURE 2HEALTH INFRASTRUCTURE – PRIVATE ........... 26 ANNEXURE 3CFLTC DETAILS................................................ 31 ANNEXURE 4HEALTH POSTS – COVID AND NON-COVID MANAGEMENT ...................................................................... 31 ANNEXURE 5MATERIAL AND SUPPLIES ............................... 47 ANNEXURE 6HR MANAGEMENT ............................................ 50 ANNEXURE 7EXPERT HEALTH TEAM VISIT .......................... 56 ANNEXURE 8HEALTH DIRECTORY ........................................ 58 2 I. THIRUVANANTHAPURAM BASIC FACTS Thiruvananthapuram, formerly Trivandrum, is the capital of Kerala, located on the west coastline of India along the Arabian Sea. It is the most populous city in India with the population of 957,730 as of 2011.Thiruvananthapuram was named the best Kerala city to live in, by a field survey conducted by The Times of India.Thiruvananthapuram is a major tourist centre, known for the Padmanabhaswamy Temple, the beaches of -

Sl. No. Name of ICTC & Address District Counsellor Contact

Sl. Name of ICTC & Address District Counsellor Contact No. ICTC in-charge Contact No. No. 1 State Pubhlic Health and Clinical Laboratory, Thiruvananthapuram-695035 Trivandrum Raji.O S 9048206828 Dr. Mary Alosiyus 9497425753 2 ICTC,MICROBIOLOGY, MEDICAL COLLEGE, THIRUVANANTHAPURAM Trivandrum JYOTHY.P.V 9895178782 Dr.Manjusree 9447428634 Trivandrum ARCHANA.R 9349517877 3 O&G DEPT., SAT HOSPITAL,TRIVANDRUM Dr.RAJESWARY PILLAI 9847939939 Trivandrum ROHINI.A.PILLAI 9447102717 4 TALUK HEAD QUARTERS HOSPITAL CHIRAYINKEEZHU -695304 Trivandrum JAYESH KUMAR K.V 9847151422 DR.H.BALACHANDRAN 9447123220 5 TALUK HOSPITAL PARASSALA- 695502 Trivandrum BINOY.C.KURUVILLA 9747008042 Dr.ANITHA SATHISH 9447890619 6 Central Prison, Poojappura - 695012 Trivandrum Mashook Sha.S 9447493035 Dr. Rajeevan 9447400014 7 DISTRICT MODEL HOSPITAL, PEROORKADA - 695005 Trivandrum CYRIL TOM 9961991014 Dr.S.Y LEELAMONY 9447695865 8 ICTC,THQH NEDUMANGAD -695541 Trivandrum SUNILKUMAR.S 9847227421 Dr.S.PRABHA 9447555051 9 ICTC, Govt Hospital, Attingal-695101 Trivandrum RADHIKA. P.R 9995441201 Not yet nominated 10 CHC POOVAR-695050 Trivandrum SREEJA.I 9497785158 Dr. Achamma 09142110060 11 CHC VIZHINJAM-695521 Trivandrum CINDA ROGER 9497013019 DR.SHEEBA DHAS 9447004400 12 CHC,PALODU- 695562 Trivandrum VINOD KUMAR.D.S 9895787819 Dr.Valsala 9447320424 13 Chest Diseases Hospital, Pulayanarkotta- 695031 Trivandrum VACANT Dr. Geena Dalus 04712448481 14 THQH, Neyyattinkara-695121 Trivandrum Biju J S 9847960044 Dr. Krishnakumar 80447122275 15 Railway Station, Trivandrum Trivandrum Almas Ashraff 9961887580 Dr. Aisha Beegam . A 9447196963 16 W&C Hospital, Thycaud-695014 Trivandrum Bindu V R 9037733871 Dr. Aisha Beegam . A 9447196963 17 GH, Varkala -695141 Trivandrum Lekshmi V S 9946133369 Dr.Geetha 9447376236 18 CHC, Puthenthoppe - 695588 trivandrum Sharlet M 9946311214 Dr. -

Accused Persons Arrested in Thiruvananthapuram City District from 24.04.2016 to 30.04.2016

Accused Persons arrested in Thiruvananthapuram City district from 24.04.2016 to 30.04.2016 Name of the Name of Name of the Place at Date & Court at Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Sec Police Arresting father of Address of Accused which Time of which No. Accused Sex of Law Station Officer, Rank Accused Arrested Arrest accused & Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 meenakshi bhavan, 24.04.16 744/16 1 Rajan Appuchettiyar 52 Nr. Sastha temple, Peroorkada Peroorkada B.Babu Station Bail 10.45 118(a)of KP act peroorkada varuvilakam puthen 24.04.15 745/16 2 manoharan varghese 52 Peroorkada Peroorkada Babu.T Station Bail veedu, mannamoola 16.30 118(a)of KP act 746/16 kulathinkara veedu, kudappanakkun 24.04.16 3 sukumaran kuttappan asari 34 279IPC&185 of Peroorkada T.Babu Station Bail Ayoorkonam nu 17.05 MV act panayil veedu, kudappanakku 24.04.16 747/16 4 Ambi krishnan kutty 57 279IPC&185 of Peroorkada T.Babu Station Bail kokkottukonam nnu 19.10 MV act 748/16 Anupama veedu, chembakamoo 24.04.16 5 sivakumar sadasivan 48 279IPC&185 of Peroorkada T.Babu Station Bail melathumele du 19.20 MV act prasanthi veedu, 24.04.16 749/16 6 sudarsanan madhavan 48 piyeevilakom, Peroorkada Peroorkada Jacob Reji Jose Station Bail 20.30 118(a)of KP act vattappara 752/16 vighnesh bhavan, 25.04.16 7 Binu santhosh Antony 30 Peroorkada 279IPC&185 of Peroorkada R.Vijayan Station Bail kudappanakkunnu 18.45 MV act 753/16 vinu bhavan, KK 25.04.16 8 vinu kumar somasekharan 39 Peroorkada 279IPC&185 of Peroorkada B.Babu Station Bail Nagar,karakulam 19.20 MV act kunnil -

Primary Prevention of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: Multiple Health Care Strategies

Indian Journal of Public Health Research & Development, October 2020, Vol. 11, No. 10 139 Primary Prevention of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: Multiple Health Care Strategies Kavitha Chandran C, Aleyamma Mathew2, Jayakumar RV3 1Assistant Professor, Dept. of Medical Education, Govt. College of Nursing, Govt.Medical College, Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala, 2Professor and Head, Division of Cancer Epidemiology & Biostatistics, Regional Cancer Centre, Medical College Thiruvananthapuram, 3MNAMS, FRCP. .CEO (rtd) Indian Institute of Diabetes, Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala and Senior Consultant, Endocrinology, Aster Medcity.Kerala. Abstract Kerala being the diabetic capital of India, need to evolve a less expensive method to reduce the tangible and intangible cost of type 2 diabetes mellitus(T2DM). Hospital based single blinded randomised controlled trial was undertaken at Indian Institute of diabetes, Kerala, India with an aim to assess the effect of multilateral health care strategies on metabolic profile. Pre-diabetic individuals were screened using American Diabetic Association criteria and randomly allocated to experimental and control group. Experimental group received 3 weeks training in yoga, exercise and healthy diet preparation. Control group received only heath counselling alone on diabetes prevention. Subjects were followed up for one year. The multiple health strategies were planned based on evidences and successfully implemented to curtail the menace of DM in India. The present paper details the multiple health care strategies and methodology addressing the primary prevention of primary prevention of T2DM. Key words: pre-diabetes, metabolic profile, life style modification, yoga Introduction Kerala. Overall prevalence of type 2 diabetes in an urban district of Kerala was 16.3%. In the 30-64 age group, Diabetes is a metabolic disease demonstrated age standardised prevalence was 13.7%. -

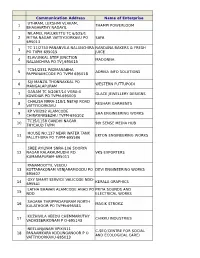

Communication Address Name of Enterprise 1 THAMPI

Communication Address Name of Enterprise UTHRAM, LEKSHMI VLAKAM, 1 THAMPI POWERLOOM BHAGAVATHY NADAYIL NILAMEL NALUKETTU TC 6/525/1 2 MITRA NAGAR VATTIYOORKAVU PO SAFA 695013 TC 11/2750 PANANVILA NALANCHIRA NANDANA BAKERS & FRESH 3 PO TVPM 695015 JUICE ELAVUNKAL STEP JUNCTION 4 MADONNA NALANCHIRA PO TV[,695015 TC54/2331 PADMANABHA 5 ADRIKA INFO SOLUTIONS PAPPANAMCODE PO TVPM 695018 SIJI MANZIL THONNAKKAL PO 6 WESTERN PUTTUPODI MANGALAPURAM GANAM TC 5/2067/14 VGRA-4 7 GLACE JEWELLERY DESIGNS KOWDIAR PO TVPM-695003 CHALISA NRRA-118/1 NETAJI ROAD 8 RESHAM GARMENTS VATTIYOORKAVU KP VIII/292 ALAMCODE 9 SHA ENGINEERING WORKS CHIRAYINKEEZHU TVPM-695102 TC15/1158 GANDHI NAGAR 10 9th SENSE MEDIA HUB THYCAUD TVPM HOUSE NO.137 NEAR WATER TANK 11 EKTON ENGINEERING WORKS PALLITHURA PO TVPM-695586 SREE AYILYAM SNRA-106 SOORYA 12 NAGAR KALAKAUMUDHI RD. VKS EXPORTERS KUMARAPURAM-695011 PANAMOOTTIL VEEDU 13 KOTTARAKONAM VENJARAMOODU PO DEVI ENGINEERING WORKS 695607 OXY SMART SERVICE VALICODE NDD- 14 KERALA GRAPHICS 695541 LATHA BHAVAN ALAMCODE ANAD PO PRIYA SOUNDS AND 15 NDD ELECTRICAL WORKS SAGARA THRIPPADAPURAM NORTH 16 MAGIK STROKZ KULATHOOR PO TVPM-695583 KUZHIVILA VEEDU CHEMMARUTHY 17 CHIKKU INDUSTRIES VADASSERIKONAM P O-695143 NEELANJANAM VPIX/511 C-SEC(CENTRE FOR SOCIAL 18 PANAAMKARA KODUNGANOOR P O AND ECOLOGICAL CARE) VATTIYOORKAVU-695013 ZENITH COTTAGE CHATHANPARA GURUPRASADAM READYMADE 19 THOTTAKKADU PO PIN695605 GARMENTS KARTHIKA VP 9/669 20 KODUNGANOORPO KULASEKHARAM GEETHAM 695013 SHAMLA MANZIL ARUKIL, 21 KUNNUMPURAM KUTTICHAL PO- N A R FLOUR MILLS 695574 RENVIL APARTMENTS TC1/1517 22 NAVARANGAM LANE MEDICAL VIJU ENTERPRISE COLLEGE PO NIKUNJAM, KRA-94,KEDARAM CORGENTZ INFOTECH PRIVATE 23 NAGAR,PATTOM PO, TRIVANDRUM LIMITED KALLUVELIL HOUSE KANDAMTHITTA 24 AMALA AYURVEDIC PHARMA PANTHA PO TVM PUTHEN PURACKAL KP IV/450-C 25 NEAR AL-UTHMAN SCHOOL AARC METAL AND WOOD MENAMKULAM TVPM KINAVU HOUSE TC 18/913 (4) 26 KALYANI DRESS WORLD ARAMADA PO TVPM THAZHE VILAYIL VEEDU OPP. -

ANNUAL REPORT 2012 - 2013 KSBB ANNUAL REPORT 2012 - 2013 Published By: Dr

KERALA STATE BIODIVERSITY BOARD ANNUAL REPORT 2012 - 2013 KSBB ANNUAL REPORT 2012 - 2013 Published by: Dr. K. P. Laladhas Member Secretary Kerala State Biodiversity Board Pallimukku, Pettah P.O., Thiruvananthapuram-695024 Phone : 0471 – 2740240, Fax : 0471 – 2740234 Email : [email protected] | Website : www.keralabiodiversity.org Design and layout www.communiquetvm.tumblr.com KERALA STATE BIODIVERSITY BOARD ANNUAL REPORT 2012 - 2013 KSBB Kerala State Biodiversity Board Pallimukku, Pettah, Thiruvananthapuram - 695 024 KSBB 1 2 KSBB CONTENTS 9 Kerala State Biodiversity Board Vision and Mission Biodiversity Exploration and Documentation Strengthening the institutional mechanism for implementing Biodiversity Act 2002 Peoples’ Biodiversity Register 10 Ongoing Projects Aquatic and Marine Biodiversity conservation Conservation of Traditional breeds and varieties Ecosystem conservation Sustainable resource utilization 21 Nature Education Children’s ecological congress Biodiversity Clubs and Shanthisthal International Day celebrations 24 26 Biodiversity Exhibitions Workshops / Seminars 29 Awareness and Training programmes 30 32 Awards / Competitions Publications 34 Representation in Expert Committees and Outreach programmes 36 Policy issues and advice to Government KSBB 3 Foreword I am happy to present the Annual Report 2012-2013, a compilation of the significant achievements and initiatives of Kerala State Biodiversity Board in Biodiversity conservation. Over the year, work on the first ever Marine Biodiversity Register was initiated and several project concepts were submitted, while some others are under development. Urban Biodiversity enhancement programme is one our flagship projects being successfully implemented in Thiruvananthapuram to promote the Dr.Oommen.V.Oommen conservation of urban natural ecosystem, ponds and other water bodies. In addition, Board has also undertaken programmes targeted at Aquatic Chairman and Marine Biodiversity Conservation, Conservation of traditional breeds and varieties and Ecosystem conservation. -

Accused Persons Arrested in Thiruvananthapuram City District from 07.06.2020To 13.06.2020

Accused Persons arrested in Thiruvananthapuram City district from 07.06.2020to 13.06.2020 Name of Name of Name of the Place at Date & Arresting the Court Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, at which No. Accused Sex Sec of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 TC 41/2426,Min House,Toll Gate Junction,Kalippankula Muhammed 39/Mal 13-06- 1166/2020/27 VIMAL SI of 1 Maheen m ward,Manacaud FORT FORT STATION BAIL Fizal e 2020/ 9 IPC Police Village, KERALA, THIRUVANANTHAPUR AM CITY, FORT TC39/884,Cheruvalli Lane, Near Punartham,Auditoria m, 42/Mal 13-06- 1167/2020/27 VIMAL SI of 2 Adithyakiran.P Pavithrakumar Kanjirampara.P.O,Vatt FORT FORT STATION BAIL e 2020/ 9 IPC Police iyoorkavau Village, KERALA, THIRUVANANTHAPUR AM CITY, TC 5/1068,DNRA 72, Kadavil Veedu,Devi Nagar, Peroorkada 41/Mal 13-06- 1168/2020/27 VIMAL SI of 3 Nivin James Ward,Kudappanakkun FORT FORT STATION BAIL e 2020/ 9 IPC Police nu Village, KERALA, THIRUVANANTHAPUR AM CITY, TC 23/1402, BIJU BHAVAN, NEAR 23/Mal 07-06- 677/2020/279 4 Sarath.S Sasi.C POPULAR SERVICE Melarannoor KARAMANA Sivakumar V.R STATION BAIL e 2020/18:23 IPC STATION, MELARANOOR TC 50/490, Marwel A3, 21/Mal Maruthoorkada 08-06- 679/2020/279 5 Aswin.V Vikraman.R Vadakkamneelam, KARAMANA Sivakumar V.R STATION BAIL e vu 2020/20:06 IPC Maruthoorkadavu, Kalady, 8921964885 TC 52/716, 682/2020/279 25/Mal Panakkalvilakam, 10-06- 6 Sarath.M Manoharan.C Chullamukku IPC & 185 MV KARAMANA Sivakumar V.R STATION BAIL e Poozhikunnu, Estate 2020/08:41 ACT P.O TC 64/1097, Ananthu Ananthu 23/Mal 10-06- 683/2020/279 7 Anil Kumar Nivas, Karumam, Karamana KARAMANA Sivakumar V.R STATION BAIL Krishnan A e 2020/12:36 IPC Melamcode ward Gollangi Chinnarao House, Nr. -

Accused Persons Arrested in Thiruvananthapuram City District from 11.04.2021To17.04.2021

Accused Persons arrested in Thiruvananthapuram City district from 11.04.2021to17.04.2021 Name of Name of the Name of the Place at Date & Arresting Court at Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Sec Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, which No. Accused Sex of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 413/2021/118( TC 21/1261, Rajamma a) of KP Act & Pratheesh Ratheesh Ramaswamy 45/Mal Bhavan, Mannamvila, 15-04- 1 Theemankari Sec.4(2)(j) r/w KARAMANA Kumar.SI of STATION BAIL Kumar Asari e TRA-121, Nedumcaud, 2021/19:15 5 of KEDO Police Karamana PO 2020 559/2021/4(2) (j) r/w 3(a) of Kerala V GANGA 32/Mal KOVALAM 15-04- 2 NAZEER YOUSAF KHAN NOUFAL MANZIL Epidemic KOVALAM PRASAD. SI of STATION BAIL e JUNCTION 2021/14:30 Diseases Police Ordinance 2020 558/2021/4(2) (j) r/w 3(a) of Kerala 23/Mal PARAMBIL VEEDU 15-04- K VINOD. SI of 3 AKHIL RAJAN AZHAKULAN JN Epidemic KOVALAM STATION BAIL e THUMBODU KALLARA 2021/12:15 police Diseases Ordinance 2020 557/2021/4(2) (j) r/w 3(a) of MARANVILAI Kerala V GANGA 52/Mal 15-04- 4 JABARAJ JAMES YHIRUVATTAR AZHAKULAN JN Epidemic KOVALAM PRASAD. SI of STATION BAIL e 2021/12:25 KANYAKUMARI Diseases Police Ordinance 2020 556/2021/Sec. 4(2)(d) r/w 5 of KUMAR BHAVAN Kerala 20/Mal MANALOOR 15-04- K VINOD. -

2018111639.Pdf

Seniority list of Employees who have registered for Govt. Quarters Sl Registration Thiruvananthapuram City No No 1 16/03 Asha.S.S., C.A. Grade II KPSC Pattom, Thiruvananthapuram 2 Girishkumar.P, Peon, Finance Department,Govt. Secretariat, 27/03 Thiruvananthapuram. 3 68/03 Leena.K.K, L.D. Typist, Museum & Zoos Dept. , TVPM 4 195/03 S. Harikumar, Sel. Grade Assistant, KPSC 5 228/03 Sijan. J. Alappat, Asst. Grade II,CRD, LMS Compound 6 38/04 Mini.M.D, CA Gr.11, KPSC, TVPM 7 KrishnaVeni. S, L.D. Typist, Director of Public Instruction, TVPM 9400032329 142/04 8 163/04 Sunojanchali, Selectrion Grade Typist, GED, Secretariat 9 K. Vijayasree, First Gr. Draftsman, Asst. Director Office, Survey Mapping 276/04 10 62/05 Sheeba. B.P, Typist Grade II, Finance, Secretariat, TVPM 11 145/05 Smt, Preetha. K, Asst. Gr. I, Legislative Secretariat, TVPM 12 191/05 A.K. Rajanesh, Typist Grade I, Kerala Legislature Secretariat 13 223/05 Smt. Jessy.V, Senior Grade typist, Directorate of Urban Affairs 14 Susamma Mathai, UD Clerk, 0/0. Stationary Controller, Thiruvananthapuram 32/06 15 Sathikumari. R, L.D. Typist, 0/o. Chief Engineer, Investigation & Design (IDRB 73/06 ),Vikas Bhavan 16 172/06 Nazia, Assistant , Kerala Legislature Secretariat 17 212/06 V.S. Rajeshkumar, Peon, College of Engineering, TVPM 18 Sii. Krishnadasan, Typist Grade I, Home (PS) Department, Govt.Secretariat 3/07 19 29/07 Girija.P,,UPSA, Govt. G.H.S.S.Cotton Hill , TVPM 20 54/07 Sunil Kumar.K.M,Section Officer, Legislative Secretariat, 21 58/07 R.Sreekala, Assistant. -

Annual Report 2016-’17

KSCSTE-NATPAC ANNUAL REPORT 2016-’17 KSCSTE-NATPAC ds ,l lh ,l Vh b & jk"Vªh; ifjogu ;kstuk ,oa vuqla/kku dsaæ KSCSTE - National Transportation Planning and Research Centre sI Fkv kn Fkv Sn C &---- --- --tZiob KXmKX Bkq{XW KthjW tI{μw An Institution of Kerala State Council for Science, Technology and Envioronment Sasthra Bhavan, Pattom - 695004, Thiruvananthapuram ANNUAL REPORT 2016-’17 KSCSTE-NATPAC National Transportation Planning and Research Centre (An Institution of Kerala State Council for Science, Technology and Environment) Sasthra Bhavan, Pattom Palace P.O, Thiruvananthapuram -695 004 www.natpac.kerala.gov.in E-Mail:[email protected] Annual Report 2016-‘17 CONTENTS Sl. Page Title No. No. SUMMARY OF PROJECTS 1 Estimation of Trip Generation Rates for Different Land Uses in Kerala State 1 Strategic Plan for the Development of National Highway Network in Kerala – 2 Kozhikode Division 3 3 Development of Traffic Growth Rate Model for National Highways in Kerala 4 Integration of Multi-Modal Transit System for Urban Areas: A Case Study of 4 5 Kochi City 5 Consultancy Services for Light Rail Transit in Thiruvananthapuram 8 Development of Feeder Route Services for Proposed Light Metro System in 6 9 Thiruvananthapuram 7 Traffic and Transportation Studies for 11 Towns in Kerala State 11 8 Feasibility of a Grade Separator at Mokavoor in Kozhikode City 29 9 Comprehensive Mobility Plan for Thrissur City in Kerala State 31 10 Parking Management Schemes for Medical College Area in Thiruvananthapuram 33 Pedestrian Grade Separated -

VSSC/P/ADV/176/2015 Dt.04.12.2015

Note :- 1. Full details and specifications of the items and general instructions to be followed regarding submission of tenders are indicated in the tender documents. 2. Tender Documents can be downloaded from our websites and also be obtained from the following address on request and submission of tender fee : For Sl. No. 1 : Sr. Purchase & Stores Officer, Main Purchase, Purchase Unit-I, VSSC, ISRO PO, Thiruvananthapuram – 695 022, Ph : 0471-256 3139 / 3523. For Sl. No. 2 : Purchase & Stores Officer, CMSE Purchase Unit, Vattiyoorkavu PO, Thiruvananthapuram – 695 013, Ph : 0471-256 9290. While requesting for Tender Documents please indicate on the envelope as “Request for Tender Documents- Tender No……….. dt……………”. 3. Tender Fee ( ` 573/-) shall be paid in the form of CROSSED DEMAND DRAFT ONLY. Other mode of payment is not acceptable. The Demand Draft should be in favour of : Accounts Officer, Main Accounts, VSSC (for item under Sl. No. 1) payable at State Bank of India, Thumba, Thiruvananthapuram & Accounts Officer, CMSE Accounts, VSSC (for item under Sl. No. 2) payable at State Bank of India, Main Branch, Statue, Thiruvananthapuram [The tender fee is NON- REFUNDABLE]. Government Departments, PSUs (both Central and State), Small Scale Industries units borne in the list of NSIC and foreign sources are exempted from submission of tender fee. Those who are coming under the above category should submit documentary evidence for the same. 4. While submitting your offer, the envelope shall be clearly superscribed with Tender No. and Due Date and to be sent to the following address. For Sl. No. 1 : Sr. Purchase & Stores Officer, Main Purchase, Purchase Unit-I, VSSC, ISRO PO, Thiruvananthapuram – 695 022, Ph : 0471-256 3139 / 3523. -

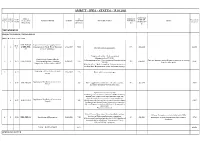

AMRUT KWA Status.Xlsx

AMRUT - KWA - STATUS - 15.01.2021 PROPOSED No: of No: of AMRUT AS PRESENT SAAP TIME OF Expenditure Project package Project ID in NAME OF WORK AS DATE AMOUNT PRESENT STATUS PROGRESS ISSUES YEAR COMPLETIO (in crores) s s MoHUA site (in Crores) (%) N TRIVANDRUM PROJECT DIVISION, TRIVANDRUM WATER SUPPLY SECTOR KER-THI-001 Improvement of water supply scheme - 15-16- 1 1 & KER-THI- Construction of 75mld Water Treatment 23/2/2017 70.00 99% -Jan-2021 42.456 17 Trial run started successfully. 017 Plant at Aruvikkara Pongumoodu office - Work completed (Inaugurated on 17/8/20.) Construction of smart office in Vellayambalam office - Work completed (Inaugurated on Only oral direction received from Corporation for starting 2 2 16-17 KER-THI-018 Thiruvananthapuram - Kowdiar, 15/08/2017 1.75 73% -Feb-2021 0.256 7/8/20), Kowdiar office work. Pongmoodu, Vellayambalam 2016-17 Kowdiar office - Work is ongoing. Column casting up to 1st floor done. Reinforcement works for beams ongoing. Supplying and Installation of smart 3 16-17 27/9/2017 2.29 Work split in to two packages meters Supplying and Installation of smart meters - 3 16-17 KER-THI-290 1.27 Meters supplied. Out of 390 meters 146 meters installed. 36% -Apr-2021 0.014 Phase I Developing interlinking software to be done. Agreement executed on 6.3.2019 Interlinking software work was entrusted with Kerala Start-up Mission & they failed to come up to the expectation. The supply & installation of smart meters were awarded to a Supplying and Installation of smart meters - 4 16-17 KER-THI-291 1.02 different agency & they could not start work since the software 0.007 Phase II development got delayed.