The First New Mexico Fife and Drum Corps I First Became Interested in Fife and Drum Music When a Found an Album in NYC Sometime in the 70S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Issue 133:Layout 1 7/21/2011 10:44 PM Page 1 I Ancienttimes Published by the Company of Fifers & Drummers, Inc

Issue 133:Layout 1 7/21/2011 10:44 PM Page 1 i AncientTimes Published by the company of Fifers & Drummers, Inc. summer 2011 Issue 133 $5.00 In thIs Issue: MusIc & ReenactIng usaRD conventIon the gReat WesteRn MusteR Issue 133:Layout 1 7/21/2011 10:45 PM Page 2 w. Alboum HAt Co. InC. presents Authentic Fife and Drum Corps Hats For the finest quality headwear you can buy. Call or Write: (973)-371-9100 1439 Springfield Ave, Irvington, nJ 07111 C.P. Burdick & Son, Inc. IMPoRtant notIce Four Generations of Warmth When your mailing address changes, Fuel Oil/excavation Services please notify us promptly! 24-Hour Service 860-767-8402 The Post Office does not advise us. Write: Membership Committee Main Street, Ivoryton P.O. Box 227, Ivoryton, CT 06442-0227 Connecticut 06442 or email: membership@companyoffife - anddrum.org HeAly FluTe COMPAny Skip Healy Fife & Flute Maker Featuring hand-crafted instruments of the finest quality. Also specializing in repairs and restoration of modern and wooden Fifes and Flutes On the web: www.skiphealy.com Phone/Fax: (401) 935-9365 email: [email protected] 5 Division Street Box 2 3 east Greenwich, RI 02818 Issue 133:Layout 1 7/21/2011 10:45 PM Page 3 Ancient times 2 Issue 133, Summer 2011 1 Fifes, Drums, & Reen - 5 Published by acting: A Wande ring The Company of Dilettante Looks for Fifers & Drummers Common Ground FRoM the eDItoR http :/ / companyoffifeanddrum.org u editor: Deirdre Sweeney 4 art & Design Director: Deirdre Sweeney Let’s Get the Music advertising Manager: t Deep River this year a Robert Kelsey Right s 14 brief, quiet lull settled in contributing editor: Bill Maling after the jam session Illustrator: Scott Baldwin 5 A Membership/subscriptions: s dispersed, and some musicians For corps, individual, or life membership infor - Book Review: at Taggarts were playing one of mation or institutional subscriptions: Dance to the Fiddle, Attn: Membership The Company of Fifers & those exquisitely grave and un - I Drummers P.O. -

Pat a Pan Fife and Drum Corps Sheet Music

Pat A Pan Fife And Drum Corps Sheet Music Download pat a pan fife and drum corps sheet music pdf now available in our library. We give you 1 pages partial preview of pat a pan fife and drum corps sheet music that you can try for free. This music notes has been read 3367 times and last read at 2021-09-28 08:10:20. In order to continue read the entire sheet music of pat a pan fife and drum corps you need to signup, download music sheet notes in pdf format also available for offline reading. Instrument: Drums, Flute, Percussion Ensemble: Drum And Bugle Corps Level: Beginning [ READ SHEET MUSIC ] Other Sheet Music With A Fife And Drum With A Fife And Drum sheet music has been read 8548 times. With a fife and drum arrangement is for Advanced level. The music notes has 6 preview and last read at 2021-10-01 00:17:47. [ Read More ] Christmastime Is Here Drum Corps Parade Music Christmastime Is Here Drum Corps Parade Music sheet music has been read 1860 times. Christmastime is here drum corps parade music arrangement is for Advanced level. The music notes has 6 preview and last read at 2021-10-01 12:39:55. [ Read More ] Little Drummer Boy Female Vocal Choir Drum Corps And Pops Orchestra Key Of Eb To F Little Drummer Boy Female Vocal Choir Drum Corps And Pops Orchestra Key Of Eb To F sheet music has been read 3829 times. Little drummer boy female vocal choir drum corps and pops orchestra key of eb to f arrangement is for Advanced level. -

USV Fife and Drum Manual Standards, Policies and Regulations

2014 USV Fife and Drum Manual Standards, Policies and Regulations Matthew Marine PRINCIPAL MUSICIAN, 2ND REGIMENT USV, 8TH NJ VOLS. VERSION 1 NOVEMBER 12, 2013 USV FIFE AND DRUM MANUAL 2 USV FIFE AND DRUM MANUAL Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................................................... 4 History .......................................................................................................................................................................................................... 4 Responsibility .............................................................................................................................................................................................. 4 Role ............................................................................................................................................................................................................. 4 Goal ............................................................................................................................................................................................................ 5 Minimum Requirements ........................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Uniforms ..................................................................................................................................................................................................... -

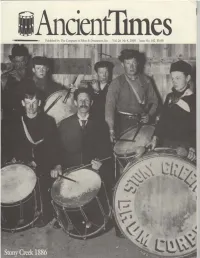

Issue #102, "Corps of Was Voted to Increase the Cover Price of the Ancient 1OK More Words While Ntuntatning a SJZC of the Same -IO Yesterday"

s Your drum head is one of the most powerful influences on your overall performance. \\'e carry a wide selection of synthetic and natural skin heads chosen expressly for rope tension lield drums, providing you with the most extensive range of choices for sound, response, and durabilit_}. We recommend BAffER HEADS these brands and Remo® Fiberskyn 3 (C11.,tM1 Rii11,,) styles ofdrum Remo® Renaissance (Cu.,1<1111 Rim.,) heads. Other Remo~ heads Swiss Kevlar are available Traditional Calfskin upon request as New Professional Calfskin well. - ti1 ,,tack Summer 2{}01 SNARE HEADS Remo® Emperor translucent (Ca.t1,1m Rim.,) Swiss Synthetic Traditional Calfskin New Professional Calfskin - tiz ,,tock Summer 2001 Cooperman File & Drum BASS HEADS Company Remo® Fiberskyn 3 Essex lnduslnal Park, P0. Box 276, 1 1 New Bear ' Kevlar Centerblook, CT 06409-0276 USA Tel: 860-767-1779 - tiz ,,tock tiz 2-1" and 26" diameter,, Fax: 860-767-7017 Traditional Calfskin Email: [email protected] -----~-=--=-=On~llle:::Wro=:~Wil;wcooperman.com Ancienffimes 2 From the 1 No. 1112-No,ombct,:?()II() Tht Corps of Yutmlay Publisher/Editor Publahcd:,; The Company of 14 Fifers cffDrummers w we come to talk ofthe fifes and drums Hanciford's Vol11nturs F&DC ofyesterday. The bcgmmngs of this Editor: Bob l>T.cl· Ctltbratts 25 ¥tars illusmous music are somewhat elusive and Senior Editor: Robin N1mu12 perhaps lost forever in antiqmty. But we Associat• Editon: can n:Oect on the history we have at hand Grrg BJcon, MUll, Editor 15 Nwithin the museum archives. J fascinanng record of fife Jc-1.~ Hili-mon. -

In This Issue: Monumental Memories Le Carillon National, Ah! Ça Ira and the Downfall of Paris, Part 1 Healy Flute Company Skip Healy Fife & Flute Maker

i AncientTimes Published by the Company of fifers & drummers, Inc. fall 2011 Issue 134 $5.00 In thIs Issue: MonuMental MeMorIes le CarIllon natIonal, ah! Ça Ira and the downfall of ParIs, Part 1 HeAly FluTe CompAny Skip Healy Fife & Flute maker Featuring hand-crafted instruments of the finest quality. Also specializing in repairs and restoration of modern and wooden Fifes and Flutes on the web: www.skiphealy.com phone/Fax: (401) 935-9365 email: [email protected] 5 Division Street Box 23 east Greenwich, RI 02818 Afffffordaordable Liability IInsurance Provided by Shoffff Darby Companiies Through membership in the Liivingving Histoory Associatiion $300 can purchaase a $3,000,000 aggregatte/$1,000,000 per occurrennce liability insurance that yyou can use to attend reenactments anywhere, hosted by any organization. Membership dues include these 3 other policies. • $5,010 0 Simple Injuries³Accidental Medical Expense up to $500,000 Aggggregate Limit • $1,010 0,000 organizational liability policy wwhhen hosting an event as LHA members • $5(0 0,000 personal liability policy wwhhen in an offfffiicial capacity hosting an event th June 22³24 The 26 Annual International Time Line Event, the ffiirst walk througghh historryy of its kind establishedd in 1987 on the original site. July 27³29 Ancient Arts Muster hosting everything ffrrom Fife & DDrum Corps, Bag Pipe Bands, craffttspeople, ffoood vendors, a time line of re-enactors, antique vehicles, Native Ameericans, museum exhibits and more. Part of thh the activities during the Annual Blueberry Festival July 27³AAuugust 5 . 9LVLWWKH /+$·VZHEVLWHDW wwwwwww.lliivviinnggghhiissttooryassn.oorg to sign up ffoor our ffrree e-newsletter, event invitations, events schedules, applications and inffoormation on all insurance policies. -

First Drums 1958 and 1959

THE DRUMS OF THE COLONIAL WILLIAMSBURG FIFES AND DRUMS VISIBLE SYMBOLS OF THE CORPS’ LEGACY BY: BILL CASTERLINE, JANUARY 21, 2012 1 FIRST DRUMS 1958 AND 1959 LEFT: Rehearsal inside the Powder Magazine just prior to the first performance on July 4, 1958, playing drums [1] borrowed from James Blair High School, and close up of one of the drums. MIDDLE LEFT: British Army drums in 1959 photo. The flag carrier on right is William “Bill” Geiger, Director of the Craft Shops and supervisor of the Militia and CWF&D. BELOW LEFT: One of three British Army drums purchased in 1959, with added “VA REGT” painted on the shell. The “worm” design on counter hoops is typical of British drums. One of the original British Army drums will return permanently to the CWF&D in 2012. BELOW RIGHT: 1959 Christmas Guns ceremony on Merchants Square, with Captain Nick Payne in uniform of the Virginia Regiment, during which ceremony original Brown Bess muskets were fired by the Militia. 2 Soistman Drums 1960 LEFT: 1958 visit of the Lancraft Fife and Drum Corps (New Haven, Conn.) provided example of top rate unit and demonstrated viability of a fife and drum corps for Colonial Williamsburg. Lancraft brought its “Grand Republic” drums (close up at left) built by Gus Moeller [2] that provided an example for Colonial Williamsburg of the authenticity and sound produced by such drums that CW was seeking since 1953 [3]. LEFT: July, 1960, training by SP5 George Carroll and Old Guard F&D musicians using a “shield” drum loaned to the Old Guard by Buck Soistman [4] and a Moeller drum from The U.S. -

056-065, Chapter 6.Pdf

Chapter 6 parts played in units. To illustrate how serious the unison, and for competition had become, prizes for best g e g e d by Rick Beckham d the technological individual drummer included gold-tipped advancement of drum sticks, a set of dueling pistols, a safety v v n The rudiments and styles of n the instruments bike, a rocking chair and a set of silver loving n n i 3 i drum and bugle corps field i and implements of cups, none of which were cheap items. percussion may never have been i field music The growth of competitions continued a t a invented if not for the drum’s t competition. and, in 1885, the Connecticut Fifers and functional use in war. Drill moves i Martial music Drummers Association was established to i that armies developed -- such as m foster expansion and improvement. Annual m competition began t the phalanx (box), echelon and t less than a decade field day musters for this association h front -- were done to the beat of h following the Civil continue to this day and the individual snare the drum, which could carry up to War, birthed in and bass drum winners have been recorded e t e t m a quarter mile. m Less than 10 years after the p Civil War, fife and drum corps p u u w organized and held competitions. w These hard-fought comparisons r brought standardization and r o o m growth, to the point that, half a m century later, the technical and d d r arrangement achievements of the r o o “standstill” corps would shape the g l g drum and bugle corps percussion l c c foundation as they traded players , a and instructors. -

006-013, Chapter 1

trumpeteers or buglers, were never called bandsmen. They had the military rank, uniform and insignia of a fifer, a drummer, a d trumpeteer or a bugler. d Collectively, they could be called the fifes l l & drums, the trumpets & drums, the drum & bugle corps, the corps of drums, the drum e e corps, or they could be referred to simply as i the drums in regiments of foot or the i trumpets in mounted units. f f Since the 19th century, the United States military has termed these soldier musicians e the “Field Music.” This was to distinguish e them from the non-combatant professional l l musicians of the Band of Music. The Field Music’s primary purpose was t t one of communication and command, t whether on the battlefield, in camp, in t garrison or on the march. To honor the combat importance of the Field Music, or a a drum corps, many armies would place their regimental insignia and battle honors on the b drums, drum banners and sashes of their b drum majors. The roots of martial field music go back to ancient times. The Greeks were known to e have used long, straight trumpets for calling e Chapter 1 commands (Fig. 1) and groups of flute players by Ronald Da Silva when marching into battle. h h The Romans (Fig. 2 -- note the soldier When one sees a field performance by a with cornu or buccina horn) used various t t modern drum and bugle corps, even a unit as metal horns for different commands and military as the United States Marine Drum & duties. -

Old-Guard-Williamsburg.Pdf

TWO OF AMERICA‟S PREEMINENT FIFE AND DRUM CORPS THE COLONIAL WILLIAMSBURG FIFES AND DRUMS AND THE U.S. ARMY OLD GUARD FIFE AND DRUM CORPS SHARE COMMON ROOTS AND LEGACY By William H. Casterline, Jr. March 15, 2010 Revised April 25, 2011 Over 50 years ago the Colonial Williamsburg Fifes and Drums made its first performance by two fifers and two drummers on July 4, 1958.1 During the 1960‟s the CW Corps became one of the preeminent fife and drum corps in America, playing traditional historic music and wearing Revolutionary War uniforms. Over the years the CW Corps, which celebrated its 50th anniversary in 2008, has become an iconic symbol of Colonial Williamsburg itself. From its earliest years, the CW Corps shared common roots and close contacts with the U.S. Army Old Guard Fife and Drum Corps, which also plays traditional historic music and wears Revolutionary War uniforms. The contacts between the two corps have continued for 50 years to this day. Indeed, in many ways, it can be said the two units are sister corps. The U.S. Army Old Guard Fife and Drum Corps celebrates its 50th anniversary this year. This corps is the only unit of its kind in the U.S. Military. It is part of the 3rd U.S. Infantry Regiment, “The Old Guard,” which is the oldest active duty infantry regiment in the U.S. Army, stationed at Ft. Myer, Virginia. The regiment received its name from General Winfield Scott during a victory parade in Mexico City in 1847 following its valorous performance in the Mexican War.2 The unit plays for parades, pageants, dignitaries and historical celebrations in Washington, D.C., and around the country. -

Published by the Company Offifcrs & Drummers, Inc. Fall 2001 Vol. 27

Published by The Company ofFifcrs & Drummers, Inc. Fall 2001 Vol. 27 No.2 Issue 104 S5.00 Sales prices are limited to the noted number of these items, and will remain in effect in effect until January 15, 2002. All of these Bass Drums goods are subject to prior sale. Order now for Spring 2002 deli\'en·. All of these shells can be reduced in \\idth to suit your needs, and will be made up with your choice ofcolon:. The listed prices are for bass Shipping and/or sales tax is not drums made with standard linings and features: any custom charges would normally included. apply to a regular bass drum order. such as the cost for artwork or extra Carl}" hooks, will • also apply co these sale drums. Shell Si'u L.11111i1t1ft•cl ,\'uml•er Price u·,ih Prict' ll'ilh Priawith (,leplh ,\' ,Ji~,) ll'~w} 11,•,11'/a/,le Rmwlleact, Cdt'llm,I.• Ke,•lar 11,·,uJ., 24' X 24' mahogany 3 reg. S 810.00 reg. $1064.00 reg.$ 861.00 sale $648.00 sale $902.00 sale $699.00 20' X 24' cherry 2 reg. $ 810.00 reg. S 1064.00 reg.$ 861.00 sale $ 648.00 sale $902.00 sale $699.00 24' X 26' birds-eye reg. S 910.00 reg. $ 1186.00 reg. $ 968.00 maple sale $728.00 sale $1004.00 sale $786.00 14'x24" ash reg.$ 670.00 reg $ 924.00 reg 721.00 hoops have 10 holes sale $500.00 sale $754.00 sale $551 .00 slightly imperfect Domestic Calfskin Heads Calfskin heads prices ha\'e undergone large price increases recently, as the on~· domestic supplier ceased operation~. -

Sources for Motwani, I NHD 2021

1 Annotated Bibliography Primary Sources 58th Presidential Inauguration. 20 Jan. 2017. Dvids, www.dvidshub.net/image/3117052/58th-presidential-inauguration. Accessed 10 Apr. 2021. This is a photograph of the United States Old Guard Fife and Drum Corps performing in the 58th Presidential Inauguration. I used this photo to show how drums are still used and perform today to incite patriotism and boost morale during important ceremonies. Band of the 114th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry [Detail], in front of Petersburg, Va., August, 1864. Aug. 1864. Library of Congress, www.loc.gov/collections/civil-war-band-music/articles-and-essays/the-american-brass-ba nd-movement/the-civil-war-bands/. Accessed 25 Feb. 2021. This is a photograph of bands in the 114th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry in front of Petersburg, VA, which was taken for record-keeping. I learned that bands of the Confederate and Union armies served their units in many ways and were highly effective in attracting new recruits. I used this information in my project to discuss the role of drums outside the military camps and battlefields. "Battle Drums." YouTube, 2 May 2017, www.youtube.com/watch?v=pwhsi9Co9y0&feature=youtu.be. Accessed 26 Feb. 2021. This is a soundtrack of war drums playing in battle. I used this in my project so the viewers of my website would know what war drums sound like. I used it in the Historical Backdrop section of my project. 2 Bircher, William. A Drummer-boy's Diary: 1861 to 1865. 1889 ed., Google Books ed., St. Pual Book and Stationery Company, 1889. -

In Camp Along the Monocacy

IN CAMP ALONG THE MONOCACY From Blue and Gray Education Society Field Headquarters in Frederick Maryland Vol. 4 Issue 1 February/March 2020 Editor: Gloria Swift Music of the Civil War Oscar Wilde, Irish poet and playwright, once said, “Music is the art which is most nigh to tears and memories”. And nothing could be any truer about music in the Civil War. Music was indeed an art. It made men want to join the army, it made them reminisce of home, or it made them lament departed comrades. Music was often a way to spend a peaceful evening with others around the campfire. It could also be the spirited piece one heard the next day Editor Gloria Swift and her assistant Fred before going into battle Music for the soldiers was all encompassing and had many meanings. We can learn to know and understand what the soldiers heard even today if we take the time to listen. Only then will we be able to understand that Oscar Wilde was right. “Music is the art which is most nigh to tears and memories”. Gloria The Music They Heard By Brian Smith On Wednesday, November 7, 1860, the packet Wide Awake brought the news of Lincoln’s victory to the little Massachusetts island of Nantucket, and that evening the islanders celebrated. “A torchlight procession of more than 150 persons gathered in the lower square on Main Street. Under the direction of Chief Marshall Charles Wood and Captain Daniel Russell, four engine companies and the Nantucket Brass Band led the parade up Main Street, stopping before the Republican headquarters where three rockets were fired into the evening air and a 100-gun salute was raised for the President elect".