International Journal of Mental Health Systems Biomed Central

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Downloaded from the ACCORD As the “Saviours”, and Darfurians Negatively As Only Just the “Survivors”

CONTENTS EDITORIAL 2 by Vasu Gounden FEATURES 3 Paramilitary Groups and National Security: A Comparison Between Colombia and Sudan by Jerónimo Delgådo Caicedo 13 The Path to Economic and Political Emancipation in Sri Lanka by Muttukrishna Sarvananthan 23 Symbiosis of Peace and Development in Kashmir: An Imperative for Conflict Transformation by Debidatta Aurobinda Mahapatra 31 Conflict Induced Displacement: The Pandits of Kashmir by Seema Shekhawat 38 United Nations Presence in Haiti: Challenges of a Multidimensional Peacekeeping Mission by Eduarda Hamann 46 Resurgent Gorkhaland: Ethnic Identity and Autonomy by Anupma Kaushik BOOK 55 Saviours and Survivors: Darfur, Politics and the REVIEW War on Terror by Karanja Mbugua This special issue of Conflict Trends has sought to provide a platform for perspectives from the developing South. The idea emanates from ACCORD's mission to promote dialogue for the purpose of resolving conflicts and building peace. By introducing a few new contributors from Asia and Latin America, the editorial team endeavoured to foster a wider conversation on the way that conflict is evolving globally and to encourage dialogue among practitioners and academics beyond Africa. The contributions featured in this issue record unique, as well as common experiences, in conflict and conflict resolution. Finally, ACCORD would like to acknowledge the University of Uppsala's Department of Peace and Conflict Research (DPCR). Some of the contributors to this special issue are former participants in the department's Top-Level Seminars on Peace and Security, a Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida) advanced international training programme. conflict trends I 1 EDITORIAL BY VASU GOUNDEN In the autumn of November 1989, a German continually construct walls in the name of security; colleague in Washington DC invited several of us walls that further divide us from each other so that we to an impromptu celebration to mark the collapse have even less opportunity to know, understand and of Germany’s Berlin Wall. -

CHAP 9 Sri Lanka

79o 00' 79o 30' 80o 00' 80o 30' 81o 00' 81o 30' 82o 00' Kankesanturai Point Pedro A I Karaitivu I. Jana D Peninsula N Kayts Jana SRI LANKA I Palk Strait National capital Ja na Elephant Pass Punkudutivu I. Lag Provincial capital oon Devipattinam Delft I. Town, village Palk Bay Kilinochchi Provincial boundary - Puthukkudiyiruppu Nanthi Kadal Main road Rameswaram Iranaitivu Is. Mullaittivu Secondary road Pamban I. Ferry Vellankulam Dhanushkodi Talaimannar Manjulam Nayaru Lagoon Railroad A da m' Airport s Bridge NORTHERN Nedunkeni 9o 00' Kokkilai Lagoon Mannar I. Mannar Puliyankulam Pulmoddai Madhu Road Bay of Bengal Gulf of Mannar Silavatturai Vavuniya Nilaveli Pankulam Kebitigollewa Trincomalee Horuwupotana r Bay Medawachchiya diya A d o o o 8 30' ru 8 30' v K i A Karaitivu I. ru Hamillewa n a Mutur Y Pomparippu Anuradhapura Kantalai n o NORTH CENTRAL Kalpitiya o g Maragahewa a Kathiraveli L Kal m a Oy a a l a t t Puttalam Kekirawa Habarane u 8o 00' P Galgamuwa 8o 00' NORTH Polonnaruwa Dambula Valachchenai Anamaduwa a y O Mundal Maho a Chenkaladi Lake r u WESTERN d Batticaloa Naula a M uru ed D Ganewatta a EASTERN g n Madura Oya a G Reservoir Chilaw i l Maha Oya o Kurunegala e o 7 30' w 7 30' Matale a Paddiruppu h Kuliyapitiya a CENTRAL M Kehelula Kalmunai Pannala Kandy Mahiyangana Uhana Randenigale ya Amparai a O a Mah Reservoir y Negombo Kegalla O Gal Tirrukkovil Negombo Victoria Falls Reservoir Bibile Senanayake Lagoon Gampaha Samudra Ja-Ela o a Nuwara Badulla o 7 00' ng 7 00' Kelan a Avissawella Eliya Colombo i G Sri Jayewardenepura -

MICE-Proposal-Sri-Lanka-Part-2.Pdf

Sri Lanka East Coast Region Trincomalee , a port city on the northeast coast of Sri Lanka. Set on a peninsula, Fort Frederick was built by the Portuguese in the 17th century. Trincomalee is one of the main centers of Tamil speaking culture on the island. The beaches are used for scuba diving, snorkeling and whale watching. The city also has the largest Dutch Fort in Sri Lanka. Best for: blue-whale watching. Arugam Bay, Arugam Bay is a unique and spectacular golden sandy beach on the East coast, located close to Pottuvil in the Ampara district. It is one of the best surfing spots in the world and hosts a number of international surfing competitions. Best for: Surfing & Ethnic Charm The beach of Pasikudah, which boasts one of the longest stretches of shallow coastline in the world. Sri Lanka ‘s Cultural Triangle Sri Lanka’s Cultural triangle is situated in the centre of the island and covers an area which includes 5 World Heritage cultural sites(UNESCO) of the Sacred City of Anuradhapura, the Ancient City of Polonnaruwa, the Ancient City of Sigiriya, the Ancient City of Dambulla and the Sacred City of Kandy. Due to the constructions and associated historical events, some of which are millennia old, these sites are of high universal value; they are visited by many pilgrims, both laymen and the clergy (prominently Buddhist), as well as by local and foreign tourists. Kandy the second largest city in Sri- Lanka and a UNESCO world heritage site, due its rich, vibrant culture and history. This historic city was the Royal Capital during the 16th century and maintains its sanctified glory predominantly due to the sacred temples. -

Leeds International School

Leeds International School 7/25, Railway Station Road, Pinwatta, Panadura, Sri Lanka. Telephone : 038-2245321/ 038 -4927373 Fax : 038-4281151 E-mail : [email protected] Website : www.leeds.lk Dear Parents/Guardians, Most importantly, we hope everyone in our Leeds community is staying healthy and safe during these turbulent times. We sincerely hope that soon we’ll be able to overcome these difficulties as a nation. If we turn our attention towards our school activities, Leeds has taken many actions to ensure our students stay active during this forced break. We finished uploading all the holiday assignments of Pack 01 and Pack 02 with other online activities for the moment, which was made available via our web site (www. leeds.lk) and Educal (School Communication app). Our A/L students are being taught through Google Classroom. Furthermore we are currently planning some more online activities to keep our kids engaged. Currently our academic and technical staffs are working hand in hand on multiple projects to plan and prepare for the times ahead. We assure you that our team is working hard to keep up with the challenges of “e learning” during this unprecedented times to give utmost for our students. Whilst thanking many parents who inquired on how Term Fees can be paid, please find below, the steps to follow to make payments for the 3rd Term. 1) Term Fee structure for the third term of Academic Year 2019/2020. Please select the relevant term fee according to your child’s class. Term Fee Structure Play Group 22,000.00 KG 1 24,000.00 KG 2 26,000.00 Primary 1 29,000.00 Primary 2 31,000.00 Primary 3 33,000.00 Primary 4 35,000.00 Primary 5 36,000.00 Form 1 / Grade 6 37,000.00 Form 2 / Grade 7 38,000.00 Form 3 / Grade 8 39,000.00 Form 4 / Grade 9 40,000.00 Form 5 / Grade 10 40,000.00 O/L Grade 11 40,000.00 Form 6 / Grade 12 44,000.00 Form 7 / Grade 13 44,000.00 2) Please select the bank details according to the branch your child is studying at. -

Dry Zone Urban Water and Sanitation Project – Additional Financing (RRP SRI 37381)

Dry Zone Urban Water and Sanitation Project – Additional Financing (RRP SRI 37381) DEVELOPMENT COORDINATION A. Major Development Partners: Strategic Foci and Key Activities 1. In recent years, the Asian Development Bank (ADB) and the Government of Japan have been the major development partners in water supply. Overall, several bilateral development partners are involved in this sector, including (i) Japan (providing support for Kandy, Colombo, towns north of Colombo, and Eastern Province), (ii) Australia (Ampara), (iii) Denmark (Colombo, Kandy, and Nuwaraeliya), (iv) France (Trincomalee), (v) Belgium (Kolonna–Balangoda), (vi) the United States of America (Badulla and Haliela), and (vii) the Republic of Korea (Hambantota). Details of projects assisted by development partners are in the table below. The World Bank completed a major community water supply and sanitation project in 2010. Details of Projects in Sri Lanka Assisted by the Development Partners, 2003 to Present Development Amount Partner Project Name Duration ($ million) Asian Development Jaffna–Killinochchi Water Supply and Sanitation 2011–2016 164 Bank Dry Zone Water Supply and Sanitation 2009–2014 113 Secondary Towns and Rural Community-Based 259 Water Supply and Sanitation 2003–2014 Greater Colombo Wastewater Management Project 2009–2015 100 Danish International Kelani Right Bank Water Treatment Plant 2008–2010 80 Development Agency Nuwaraeliya District Group Water Supply 2006–2010 45 Towns South of Kandy Water Supply 2005–2010 96 Government of Eastern Coastal Towns of Ampara -

SRI LANKA 2019 the Details

T A V E R N A T R A V E L S P R E S E N T S S R I L A N K A J U N E 2 0 1 9 G R O U P T R I P J U N E 1 - 9 T H , 2 0 1 9 ONLY $1,400 SRI LANKA 2019 the details JUNE 1 - 9 • 2019 $1,400 what's included? This 8 day adventure is jam-packed wit are a mix of local and luxury! The goal is to keep the cost of the trip as low as possible, while still providing an adventure filled trip! WHAT'S INCLUDED WHAT'S NOT INCLUDED - 8 NIGHTS ACCOMMODATION - FLIGHTS IN SHARED ROOMS - VISA - WELCOME DINNER - TRAVEL INSURANCE - 2 MEALS A DAY - DRINKS - PRIVATE DRIVER - PERSONAL - GROUP PHOTOGRAPHER INCIDENTALS EXPENSES - DAILY ACTIVITIES - OPTIONAL ACTIVITIES SRI LANKA JUNE 2019 activities list of example included activities - VI S I T T O L OCAL T EMPL ES AND S T AT UES - GUI DED HI KES - EL EPHANT S AF ARI - COOKI NG CL AS S - YOGA CL AS S - VI S I T T O T EA PL ANT AT I ON the itinerary 8 ACTIVITY FILLED DAYS IN COLOMBO, KANDY, HAPUTALE, ELLA, AND WELIGAMA. BUSTLING CITIES, ROLLING HILLS, SANDY BEACHES.. THIS TRIP COVERS IT ALL! DAY TRIPS ACCOMMODATIONS SIRIGIYA INCLUDE: UDAWALAWE 5 STAR SUITES MIRISSA HOSTELS UNAWATUNA HOMESTAYS GALLE AIRBNB DAY 1 Meet in Colombo Spend the afternoon exploring the city Welcome dinner buffet DAY 2 Early morning pickup for drive to Kandy Explore the bustling city of Kandy with visits to the Bahiravokanda Vihara Buddha, local temples, and the market. -

CSRP 'Project to Enhance SUTI in Colombo Metropolitan Region (CMR)'

Social Safeguard CSRP Railway Project (SSRP ) ‘Project to Enhance Colombo SUTI in Colombo Suburban Railway Metropolitan Region Project (CSRP) (CMR)’ Colombo Suburban Railway Project – ADB Funded Develop Sri Lanka Railways to cater demand in the next twenty years Colombo by following applicable guidelines Suburban (SL and ADB) Railway and Project (CSRP) by utilising the available funds effectively Project Interventions • All interventions will be focused towards Railway Electrification • But, following interventions will be undertaken, to make Railway Electrification sustainable . • Track Rehabilitation to make SLR tracks complying with accepted standard and to operate trains at the speed of 100 km/hr. • New Track Construction to avoid existing bottlenecks and to cater future demand. • Replacement of Railway/Road Bridges to facilitate clearance for Electrification • Access Electric Multiple Units (Six Car Train Sets ; Two coupled to carry 2200 passengers ( 6 persons in one sq. meter) • Signalling and Telecommunication to achieve Safety and Minimum possible Headway • Station Development to facilitate, accessibility, park & ride, multi modal operation (with Bus, LRT etc.) • Grade Separation at Level Crossings • Electrification Cost of Operation – Electric vs Diesel (DMU) I Econ Electric Operation Cost in LKR per Train-km Fuel / Electricity Cost Fuel Consumption : 2.5 lit/km 40% less than Diesel (DMU) Electricity Consumption : 5.5 kWh/km Lubricants 20% less then Diesel Maintenance 35 % less that Diesel Maintenance Operation and other Misc. Cost 30 % less then Diesel Overhead Equipment maintenance Cost To be Considered Source: IESL Report for Railway Electrification, June 2008 Railway Electrification from Veyangoda to Kaluthara by Prof. Bandara , January 2012 Railway Electrification and its Economics by Dr. -

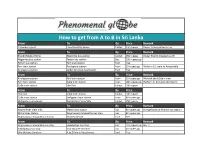

How to Get from a to B in Sri Lanka

How to get from A to B in Sri Lanka From To By Price Remark Colombo airport Erandi Holiday Home tuktuk 250 rupees Owner Erandi picked us up From To By Price Remark Erandi Holiday Home Negombo bus station tuktuk 250 rupees Owner Erandi dropped us off Negombo bus station Pettah bus station Bus 200 rupees pp Pettah bus station Fort train station foot free Fort train station Kirulapona station train 10 rupees pp Platform 10, train to Avissawella Kirulapona station Siebel Serviced Apartments foot free From To By Price Remark Kirulapona station Fort train station train 10 rupees pp We took the 8.10am train Fort train station Galle train station train 180 rupees pp Platform 5, 2nd class (10.30am) Galle train station The One tuktuk 100 rupees From To By Price Remark The One Galle train station tuktuk 100 rupees Galle train station Weligama train station train 60 rupees pp Weligama train station Naomi River View Villa tuktuk 150 rupees From To By Price Remark Naomi River View Villa Matara bus station bus 50 rupees pp change buses at Matara bus station Matara bus station Wajirawansa Maawatha bus stop bus 50 rupees pp Wajirawansa Maawatha bus stop Seaview Resort foot free From To By Price Remark Wajirawansa Maawatha bus stop Embilipitiya bus stop bus 110 rupees pp Bus 11 Embilipitiya bus stop Uda Walawe Junction bus 50 rupees pp Uda Walawe Junction A to Z Family Guesthouse foot free How to get from A to B in Sri Lanka From To By Price Remark Uda Walawe Junction Welawaya bus station bus 100 rupees pp Bus 98 Welawaya bus station Ella (bus stop is -

(DFAT) Country Information Report on Sri Lanka of 4 November 2019

July 2020 Comments on the Australian Government Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade’s (DFAT) Country Information Report on Sri Lanka of 4 November 2019 Contents About ARC ................................................................................................................................... 2 Introductory remarks on ARC’s COI methodology ......................................................................... 3 General methodological observations on the DFAT Country report on Sri Lanka ............................ 5 Section-specific observations on the DFAT Country report on Sri Lanka ....................................... 13 Economic Overview, Economic conditions in the north and east ........................................................ 13 Security situation, Security situation in the north and east ................................................................. 14 Race/Nationality; Tamils ....................................................................................................................... 16 Tamils .................................................................................................................................................... 20 Tamils: Monitoring, harassment, arrest and detention ........................................................................ 23 Political Opinion (Actual or Imputed): Political representation of minorities, including ethnic and religious minorities .............................................................................................................................. -

Lions Clubs International Club Membership Register

LIONS CLUBS INTERNATIONAL CLUB MEMBERSHIP REGISTER SUMMARY THE CLUBS AND MEMBERSHIP FIGURES REFLECT CHANGES AS OF JULY 2017 MEMBERSHI P CHANGES CLUB CLUB LAST MMR FCL YR TOTAL IDENT CLUB NAME DIST NBR COUNTRY STATUS RPT DATE OB NEW RENST TRANS DROPS NETCG MEMBERS 3846 025586 COLOMBO HOST REP OF SRI LANKA 306 A1 4 07-2017 32 0 0 0 0 0 32 3846 025591 DEHIWALA MT LAVINIA REP OF SRI LANKA 306 A1 4 07-2017 39 0 0 0 0 0 39 3846 025592 GALLE REP OF SRI LANKA 306 A1 4 07-2017 46 0 0 0 0 0 46 3846 025604 MORATUWA RATMALANA LC REP OF SRI LANKA 306 A1 4 07-2017 35 0 0 0 -1 -1 34 3846 025611 PANADURA REP OF SRI LANKA 306 A1 4 07-2017 32 0 0 0 0 0 32 3846 025614 WELLAWATTE REP OF SRI LANKA 306 A1 4 07-2017 32 0 0 0 -4 -4 28 3846 030299 KOLLUPITIYA REP OF SRI LANKA 306 A1 4 07-2017 17 0 0 0 0 0 17 3846 032756 MORATUWA REP OF SRI LANKA 306 A1 4 07-2017 50 0 0 0 -2 -2 48 3846 036615 TANGALLE REP OF SRI LANKA 306 A1 4 07-2017 30 0 0 0 0 0 30 3846 038353 KOTELAWALAPURA REP OF SRI LANKA 306 A1 4 06-2017 28 0 0 0 0 0 28 3846 041398 HIKKADUWA REP OF SRI LANKA 306 A1 4 06-2017 20 0 0 0 0 0 20 3846 041399 WADDUWA REP OF SRI LANKA 306 A1 4 07-2017 38 0 0 0 0 0 38 3846 043171 BALAPITIYA REP OF SRI LANKA 306 A1 4 06-2017 14 0 0 0 0 0 14 3846 043660 MORATUWA MORATUMULLA REP OF SRI LANKA 306 A1 4 07-2017 20 0 0 0 0 0 20 3846 045938 KALUTARA CENTRAL REP OF SRI LANKA 306 A1 4 06-2017 21 0 0 0 0 0 21 3846 046170 GALKISSA REP OF SRI LANKA 306 A1 4 07-2017 43 1 0 0 0 1 44 3846 048945 DEHIWALA METRO REP OF SRI LANKA 306 A1 4 07-2017 20 0 0 0 0 0 20 3846 051562 ALUTHGAMA -

SRI LANKA Floods and Storms

SRI LANKA: Floods and 29 April 1999 storms Information Bulletin N° 01 The Disaster Unusually heavy rains for this time of year and violent thunderstorms along the western and south-western coast of Sri Lanka between 16 and 21 April caused widespread damage and severe floods in the south-west and south of the country. The main rivers, Kelani and Kalu, rose by over seven feet, and caused additional flooding, made worse by slow run-off. Some of the worst areas received as much as 290 mm of rain in 24 hours, and even the capital, Colombo, where 284 mm fell within 24 hours, experienced bad flooding in many sectors of the city. The worst affected districts are Ratnapura, Colombo, Kalutara, Gampaha, Galle, Kandy, Matara and Kegalle, all located between the coast and the Kandyan highlands. Six persons were reported killed by lightning, landslides or floods. Thousands of houses were damaged or destroyed, and initial official figures place the number of homeless at around 75,000 families (the average family in Sri Lanka consists of five members). In Colombo alone an estimated 12,400 families were affected. The damage is reportedly much worse in the rural areas particularly in Ratnapura District, but precise information is difficult to come by since many of the affected areas are totally cut off, with roads inundated and power and telephone lines damaged. The railway line from Colombo to Kandy has been blocked since 19 April, when boulders from a landslide damaged the tracks. FirstDistricts estimates of affected people areSub-Divisions as follows: -

The Haputale and Bandarawela Extensions of the Ceylon Government Railway, with Notes Upon Other Railways Recently Constructed in the Colony.” by FRANCISJOHN WARING, M

272 WARING ON TIIE CEYLON GOVERNMENT RAILWAYS. [Selected SECT.11.-OTHER SELECTED PAPERS. (Paper No. 3010.) ‘I The Haputale and Bandarawela Extensions of the Ceylon Government Railway, with Notes upon other Railways Recently Constructed in the Colony.” By FRANCISJOHN WARING, M. Inst. C.E. THEobject of the present Paper is to supplement those presented to the Institution by Mr. J. R. Mosse, M. Inst. C.E., in 1880,’ and by the Author in 1887,2 by an account of the recent exten- sions to the Ceylon Government Railways, all of which are of 5 feet 6 inches gauge, with particular reference to the Haputale and Bandarawela Railways, where the magnitude of the works, entailed by the difficult country traversed, offers special points of interest. THE HAPUTALERAILWAY. This line isa further extension, about 254 miles in length, into the Province of Uva, of the Nanuoya Railway, and crosses the main dividing ridge of the island, traversing a country evenmore broken and mountainous than that through which the Nanuoya line passes. Its construction was sanctioned by the Secretary of State for the Colonies in February, 1888, and the workswere begun on the15th March, 1889; theintervening time having been occupied in engaging and sending out the staff, despatching to the Colony the necessary plant and materials, acquiring the land and other preliminaryoperations. Curves and Gradients.-Starting at Nanuoya, 5,292 feet above the sea, it rises, at the summit at Pattipola, Ilk miles distant, to analtitude of 6,224.5feet, and thence falls to 4,698 feet at Haputale. The following is a summary of the gradients :- l Minutes of Proceedings Inst.