SALVANOU Migrants Nights

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DESTE Foundation Project Space Slaughterhouse, Hydra Duration

Ίδρυµα ∆ΕΣΤΕ Εµ. Παππά & Φιλελλήνων 11. 142 34 Νέα Ιωνία ΑΘήνα Ελλάς DESTE Foundation 11 Filellinon & Em. Pappa St. 142 34 Nea Ionia Athens Greece WWW . DESTE . GR T — 30 210 27 58 490 F — 30 210 27 54 862 DESTE Foundation Project Space Slaughterhouse, Hydra Duration: June 21 – September 30, 2016 Opening Hours, Monday - Sunday: 11:00 - 13:00 & 19:00 – 22:00 Tuesday Closed — Project Coordinator: Marina Vranopoulou [email protected] — Media Contact: Regina Alivisatos [email protected] — Page 1 of 3 Ίδρυµα ∆ΕΣΤΕ “PUTIFERIO” Εµ. Παππά & Φιλελλήνων 11. A Project by Roberto Cuoghi 142 34 Νέα Ιωνία ΑΘήνα Ελλάς Candidates from the deep water DESTE Foundation Clashed with wasps they came to slaughter 11 Filellinon & Em. Pappa St. 142 34 Nea Ionia Pinching here, biting there, Athens Greece Oh my fellows please beware! WWW . DESTE . GR Smoke and flames, stink and froth, T — 30 210 27 58 490 F — 30 210 27 54 862 Splashing in a sulfurous broth Fished out at the seaside Unarmed, more dead than alive The candidates in the eventide Took your logic for a ride Internationally renowned Italian artist Roberto Cuoghi will be carrying out a major exhibition on the island of Hydra. Cuoghi was commissioned by the DESTE Foundation in the context of an exhibition program specially designed for the Foundation’s Project Space in the island’s former Slaughterhouse. Cuoghi’s exhibition is entitled “Putiferio”, in Latin "to bring the stink". “Putiferio” may also signify chaos or a small taste of hell. During the opening, the artist will transform the area around the Slaughterhouse into a camp to experiment archaic firing techniques for ceramic. -

Abai, Oracle of Apollo, 134 Achaia, 3Map; LH IIIC

INDEX Abai, oracle of Apollo, 134 Aghios Kosmas, 140 Achaia, 3map; LH IIIC pottery, 148; migration Aghios Minas (Drosia), 201 to northeast Aegean from, 188; nonpalatial Aghios Nikolaos (Vathy), 201 modes of political organization, 64n1, 112, Aghios Vasileios (Laconia), 3map, 9, 73n9, 243 120, 144; relations with Corinthian Gulf, 127; Agnanti, 158 “warrior burials”, 141. 144, 148, 188. See also agriculture, 18, 60, 207; access to resources, Ahhiyawa 61, 86, 88, 90, 101, 228; advent of iron Achaians, 110, 243 ploughshare, 171; Boeotia, 45–46; centralized Acharnai (Menidi), 55map, 66, 68map, 77map, consumption, 135; centralized production, 97–98, 104map, 238 73, 100, 113, 136; diffusion of, 245; East Lokris, Achinos, 197map, 203 49–50; Euboea, 52, 54, 209map; house-hold administration: absence of, 73, 141; as part of and community-based, 21, 135–36; intensified statehood, 66, 69, 71; center, 82; centralized, production, 70–71; large-scale (project), 121, 134, 238; complex offices for, 234; foreign, 64, 135; Lelantine Plain, 85, 207, 208–10; 107; Linear A, 9; Linear B, 9, 75–78, 84, nearest-neighbor analysis, 57; networks 94, 117–18; palatial, 27, 65, 69, 73–74, 105, of production, 101, 121; palatial control, 114; political, 63–64, 234–35; religious, 217; 10, 65, 69–70, 75, 81–83, 97, 207; Phokis, systems, 110, 113, 240; writing as technology 47; prehistoric Iron Age, 204–5, 242; for, 216–17 redistribution of products, 81, 101–2, 113, 135; Aegina, 9, 55map, 67, 99–100, 179, 219map subsistence, 73, 128, 190, 239; Thessaly 51, 70, Aeolians, 180, 187, 188 94–95; Thriasian Plain, 98 “age of heroes”, 151, 187, 200, 213, 222, 243, 260 agropastoral societies, 21, 26, 60, 84, 170 aggrandizement: competitive, 134; of the sea, 129; Ahhiyawa, 108–11 self-, 65, 66, 105, 147, 251 Aigai, 82 Aghia Elousa, 201 Aigaleo, Mt., 54, 55map, 96 Aghia Irini (Kea), 139map, 156, 197map, 199 Aigeira, 3map, 141 Aghia Marina Pyrgos, 77map, 81, 247 Akkadian, 105, 109, 255 Aghios Ilias, 85. -

Registration Certificate

1 The following information has been supplied by the Greek Aliens Bureau: It is obligatory for all EU nationals to apply for a “Registration Certificate” (Veveosi Engrafis - Βεβαίωση Εγγραφής) after they have spent 3 months in Greece (Directive 2004/38/EC).This requirement also applies to UK nationals during the transition period. This certificate is open- dated. You only need to renew it if your circumstances change e.g. if you had registered as unemployed and you have now found employment. Below we outline some of the required documents for the most common cases. Please refer to the local Police Authorities for information on the regulations for freelancers, domestic employment and students. You should submit your application and required documents at your local Aliens Police (Tmima Allodapon – Τμήμα Αλλοδαπών, for addresses, contact telephone and opening hours see end); if you live outside Athens go to the local police station closest to your residence. In all cases, original documents and photocopies are required. You should approach the Greek Authorities for detailed information on the documents required or further clarification. Please note that some authorities work by appointment and will request that you book an appointment in advance. Required documents in the case of a working person: 1. Valid passport. 2. Two (2) photos. 3. Applicant’s proof of address [a document containing both the applicant’s name and address e.g. photocopy of the house lease, public utility bill (DEH, OTE, EYDAP) or statement from Tax Office (Tax Return)]. If unavailable please see the requirements for hospitality. 4. Photocopy of employment contract. -

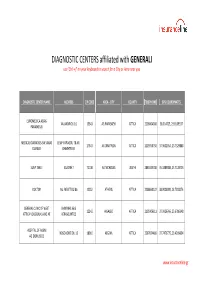

DIAGNOSTIC CENTERS Affiliated with GENERALI Use 'Ctrl + F' on Your Keyboard to Search for a City Or Area Near You

DIAGNOSTIC CENTERS affiliated with GENERALI use 'Ctrl + f' on your keyboard to search for a City or Area near you DIAGNOSTIC CENTER NAME ADDRESS ZIP CODE AREA - CITY COUNTY TELEPHONE GPS COORDINATES EUROMEDICA AGIAS XALANDRIOU 16 15343 AG PARASKEVI ATTICA 2106004000 38.014925, 23.8169337 PARASKEVIS MEDICAL DIAGNOSIS-SALVARAS LEWF.PAPAGOU 78 AG. 17343 AG DIMITRIOS ATTICA 2109750750 37.9602054, 23.7529888 IOANNIS DHMHTRIOS SUNY TABLE KAZANH 7 72100 AG NICHOLAS LASITHI 2841023700 35.1883088, 25.7128723 DOCTOR AG. MELETIOU 86 11252 ATHENS ATTICA 2108660222 38.0003909, 23.7318274 GENERAL CLINIC OF WEST SMYRNHS 36 & 12242 AIGALEO ATTICA 2105906611 37.9926766, 23.6786348 ATTICA VOUGIOUKLAKIO AE KERASOUNTOS HOSPITAL OF AIGINI NOSOKOMEIOU 10 18010 AEGINA ATTICA 2297024489 37.7473775, 23.4299604 AG.DIONUSIOS www.insuranceline.gr ELIKHS 34 KAI AIDIALEWS RADIOGRAPHY OF AEGEAN 25100 AIGIO ACHAIA 2691062700 38.2484992, 22.0911009 88 EUROMEDICA DHMHTRAS 21 68100 ALEXANDROUPOLI EVROS 2551089990 40.8491364, 25.8650806 ALEXANDROUPOLIS BIOCARE MEDICAL CENTER OF L. VOULIAGMENHS 562 17456 ALIMOS ATTICA 2109949562 37.9165572, 23.7440684 ALIMOS SYNCHRONOS ASKLIPIOS SA OTHWNOS 1 17455 ALIMOS ATTICA 2109821200 37.9208608, 23.7062464 EUROMEDICA AMPELOKIPON MESOGEIWN 2-4 11523 AMPELOKIPI ATTICA 2107470700 37.9847187, 23.7605037 EUROMEDICA AMPELOKIPON MARATHWNOS 14 56121 AMPELOKIPI THESSALONIKI 2310720020 40.6532014, 22.9193792 L.KHFISIAS 98 & ERYTHROU ORASIS AMPELOKIPON 11526 AMPELOKIPI ATTICA 2106998961 37.9927348, 23.7676253 STAVROU 2 ATHANASIADOU 9 & ATHENS EUROCLINIC 11521 AMPELOKIPI, ATHENS ATTICA 2106416600 37.9861342, 23.7564033 PARODOS D.SOUTSOU HARD ANASTASIOS AG. KWNSTANTINOU 4 21200 ARGOS ARGOLIDA 2751069201 37.6333241, 22.7300156 www.insuranceline.gr SOUHDIAS & GAKIS MICHAEL 28100 ARGOSTOLI KEPHALONIA 2671023451 38.1689764, 20.4931264 THEMISTOKLEOUS ASPROPYRGOS IONIA -EUROMEDICA PRIVATE 17o XLM N.E.O. -

EUROPEAN SOCIAL CHARTER the GOVERNMENT of GREECE • Follow up to Collective Complaints • Complementary Information on Article

28/08/2015 RAP/Cha/GRC/25(2015) EUROPEAN SOCIAL CHARTER 25th National Report on the implementation of the European Social Charter submitted by THE GOVERNMENT OF GREECE Follow up to Collective Complaints Complementary information on Articles 11§2 and 13§4 (Conclusions 2013) __________ Report registered by the Secretariat on 28 August 2015 CYCLE XX-4 (2015) 25th Greek Report on the European Social Charter Follow-up to the decisions of the European Committee of Social Rights relating to Collective Complaints (2000 – 2012) Ministry of Labour, Social Security & Social Solidarity May 2015 25th Greek Report on the European Social Charter TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Collective Complaint 8/2000 “Quaker Council for European Affairs v. Greece” .......... 4 2. Collective Complaints (a) 15/2003, “European Roma Rights Centre [ERRC] v. Greece” & (b) 49/2008, “International Centre for the Legal Protection for Human Rights – [INTERIGHTS] v. Greece” ........................................................................................................ 8 3. Collective Complaint 17/2003 “World Organisation against Torture [OMCT] v. Greece” ................................................................................................................................. 12 4. Collective Complaint 30/2005 “Marangopoulos Foundation for Human Rights v. Greece” ................................................................................................................................. 19 5. Collective Complaint “General Federation of Employees of the National Electric -

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Materials Figure S1. Temperature‐mortality association by sector, using the E‐OBS data. Municipality ES (95% CI) CENTER Athens 2.95 (2.36, 3.54) Subtotal (I-squared = .%, p = .) 2.95 (2.36, 3.54) . EAST Dafni-Ymittos 0.56 (-1.74, 2.91) Ilioupoli 1.42 (-0.23, 3.09) Kessariani 2.91 (0.39, 5.50) Vyronas 1.22 (-0.58, 3.05) Zografos 2.07 (0.24, 3.94) Subtotal (I-squared = 0.0%, p = 0.689) 1.57 (0.69, 2.45) . NORTH Aghia Paraskevi 0.63 (-1.55, 2.87) Chalandri 0.87 (-0.89, 2.67) Galatsi 1.71 (-0.57, 4.05) Gerakas 0.22 (-4.07, 4.70) Iraklio 0.32 (-2.15, 2.86) Kifissia 1.13 (-0.78, 3.08) Lykovrisi-Pefki 0.11 (-3.24, 3.59) Marousi 1.73 (-0.30, 3.81) Metamorfosi -0.07 (-2.97, 2.91) Nea Ionia 2.58 (0.66, 4.54) Papagos-Cholargos 1.72 (-0.36, 3.85) Penteli 1.04 (-1.96, 4.12) Philothei-Psychiko 1.59 (-0.98, 4.22) Vrilissia 0.60 (-2.42, 3.71) Subtotal (I-squared = 0.0%, p = 0.975) 1.20 (0.57, 1.84) . PIRAEUS Aghia Varvara 0.85 (-2.15, 3.94) Keratsini-Drapetsona 3.30 (1.66, 4.97) Korydallos 2.07 (-0.01, 4.20) Moschato-Tavros 1.47 (-1.14, 4.14) Nikea-Aghios Ioannis Rentis 1.88 (0.39, 3.39) Perama 0.48 (-2.43, 3.47) Piraeus 2.60 (1.50, 3.71) Subtotal (I-squared = 0.0%, p = 0.580) 2.25 (1.58, 2.92) . -

Theme Europan7

europan7 Nea Ionia Magnesia, Ellàs theme conurbation / site programme / issues screens 1 / 2 / 3 / 4 Population around 40 000 Theme The whole area is typical of one that has undergone Location erratic construction, but nonetheless represents a vast open space suitable for urban regeneration and / the creation of housing. Study area 99.5 ha Site area 21 ha europan7 Nea Ionia Magnesia, Ellàs theme conurbation / site programme / issues screens 1 / 2 / 3 / 4 Conurbation Site Nea Ionia and Volos together form a large town, Aliveri is a development zone to the north west of the located at the centre of the country and town of Nea Ionia. A large number of Romany gypsies stretching out towards the east. In 1922 there live in the zone, and their culture is very different from was a large influx of refugees into the town from that of the town's other inhabitants, something that is Asia Minor. These people played an important particularly noticeable in economic and social terms. role in the formation of the town's present day The Xirias stream forms a natural border to the zone, social and economic make-up. Currently, Nea and drains all the area to the west. It is, however, a Ionia is much like all modern towns in Greece. natural element that is in danger of disappearing Composed of a historical centre and three rural because of the never-ending arrival of new inhabitants. areas, numerous factories were once located in the town which greatly polluted the environment. These have now moved to an industrial zone in Volos. -

Civil Affairs Handbook on Greece

Preliminary Draft CIVIL AFFAIRS HANDBOOK on GREECE feQfiJtion Thirteen on fcSSLJC HJI4LTH 4ND S 4 N 1 T £ T I 0 N THE MILITARY GOVERNMENT DIVISION OFFICE OF THE PROVOST MARSHAL GENERAL Preliminary Draft INTRODUCTION Purposes of the Civil Affairs Handbook. International Law places upon an occupying power the obligation and responsibility for establishing government and maintaining civil order in the areas occupied. The basic purposes of civil affairs officers are thus (l) to as- sist the Commanding General of the combat units by quickly establishing those orderly conditions which will contribute most effectively to the conduct of military operations, (2) to reduce to a minimum the human suffering and the material damage resulting from disorder and (3) to create the conditions which will make it possible for civilian agencies to function effectively. The preparation of Civil Affairs Handbooks is a part of the effort of the War Department to carry out this obligation as efficiently and humanely as is possible. The Handbooks do not deal with planning or policy. They are rather ready reference source books of the basic factual information needed for planning and policy making. Public Health and Sanitation in Greece. As a result of the various occupations, Greece presents some extremely difficult problems in health and sanitation. The material in this section was largely prepared by the MILBANK MEMORIAL FUND and the MEDICAL INTELLI- GENCE BRANCH OF THE OFFICE OF THE SURGEON GENERAL. If additional data on current conditions can be obtained, it willJse incorporated in the final draft of the handbook for Greece as a whole. -

View Responsibility Report

PIRAEUS BANK CORPOraTE R1espOnsibiLITY REPORT 2012 Corporate Responsibility Report 2012 PIRAEUS BANK 2 Corporate Responsibility Report 2012 PIRAEUS BANK 3 Light heightens the sense of sight; it makes objects visible and reveals the path to a new step – the next one. There is an image of light in every page of this report. The clarity, purity and allurement of light as they are reflected at Piraeus Group headquarters, at CityLink and at PIOP sites and museums were exquisitely captured by photographer Platon Rivellis. Corporate Responsibility Report 2012 PIRAEUS BANK 4 Final review date for the Corporate Responsibility Report: June, 20, 2013 Corporate Responsibility Report 2012 PIRAEUS BANK 5 CONTENTS Chairman’s Note 7 Selected Figures Αssociated with 2012 Corporate Responsibility 8 Corporate Responsibility Key Actions and Targets 10 Corporate Responsibility Principles 14 Stakeholders’ Dialogue 15 UN Global Compact 17 Participation in Organizations and CSR Indices and Distinctions 18 Chapter 1 Corporate Governance 23 Chapter 2 Customer and Supplier Relationships 35 Chapter 3 Human Resources 47 Chapter 4 Society, Culture and the Environment 61 Ιndependent Assurance Report 89 Appendix GRI Reporting Content 93 Corporate Responsibility Report 2012 PIRAEUS BANK 6 Corporate Responsibility Report 2012 PIRAEUS BANK 7 CHAIRMAN’S Note The Greek banking system is entering a new era, following its stant development and to the necessary balance between restructuring and the recapitalization of Greek banks. For Piraeus personal and professional life, Bank, this new era signals an opportunity for a new start , as it has - our suppliers, our business partners as well as our social achieved, through its business choices in the last few months, a partners on a mutual benefit basis and in harmonious col- much greater presence in the Greek market with strong capital ad- laboration, equacy ratios. -

2003-1110 Floril'ge Gr'ce EN

2003 en ÅËËÁÄÁ Regions in action, a country on the move A selection of successful projects supported by the Structural Funds in Greece European Commission The European Commission wishes to thank the national, regional and local organisations, including private enterprises, which collaborated and provided the necessary information for this publication. Photographs (pages): Mike St Maur Sheil (1, 2-3, 4-5, 6, 7, 10, 11, 13, 18, 19, 20, 21, 23, 24, 25, 29, 32, 33, 35, 39), National Centre for Marine Research (9), Egnatia Odos SA (14), DEPA (15), Ministry of Development (16, 17), Thessaloniki International Fair SA, Central Greece Region (26), Western Macedonia Region (28), Region of the Ionian Islands (30), Regional phytosanitary protection and quality control centre of Ioannina (31), Northern Aegean Sea Region (34), Cultural Foundation of the Bank of Piraeus (36), Larissa Employment Promotion Centre (37), DEH SA (40), Special management service for URBAN Community initiative programmes, AN.KA SA (42), Marine Biology Institute of Crete (43). Cover picture: a metro station in Athens. Further information on the EU Structural Funds can be found at the following address: European Commission Directorate-General for Regional Policy http://europa.eu.int/comm/regional_policy/index_en.htm Additional information on the European Union is available on the Internet. It can be accessed through the Europa server (http://europa.eu.int). The European Commission publishes this brochure to enhance public access to information about its initiatives, European Union policies in general and the ERDF in particular. Our goal is to keep this information timely and accurate. If errors are brought to our attention, we will try to correct them. -

ANNUAL REPORT 2004 Piraeusuk 1 26.Qxd 13/04/05 14:39 “ Æ1

Cover_UK.qxd 07/04/05 13:25 “ Æ2 ANNUAL REPORT 2004 PiraeusUK_1_26.qxd 13/04/05 14:39 “ Æ1 CONTENTS BRIEF OVERVIEW 2 PIRAEUS GROUP: A DYNAMIC GROWTH COURSE 3 CHAIRMAN’S REPORT 5 DEVELOPMENTS IN THE INTERNATIONAL AND GREEK ECONOMIES 9 CONSOLIDATED FIGURES OF PIRAEUS GROUP 10 FIGURES OF PIRAEUS BANK 11 ANALYSIS OF FIGURES AND RESULTS OF PIRAEUS GROUP 12 RETAIL BANKING 18 CORPORATE BANKING 23 E-BANKING (WINBANK, ATM) 29 INTERNATIONAL ACTIVITIES 30 INVESTMENT BANKING 35 ASSET MANAGEMENT 39 REAL ESTATE DEVELOPMENT AND MANAGEMENT 42 TECHNOLOGY AND INFRASTRUCTURES 44 RISK MANAGEMENT 47 HUMAN RESOURCES 51 CORPORATE GOVERNANCE 55 SOCIETY AND ENVIRONMENT 59 CUSTOMER RELATIONS 65 SHARE PRICE DEVELOPMENT AND PERFORMANCE 67 ADOPTION OF THE INTERNATIONAL FINANCIAL REPORTING STANDARDS 70 GROWTH GOALS AND PROSPECTS OF PIRAEUS BANK GROUP 72 CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS AS AT 31 DECEMBER 2004 74 ANALYSIS OF FIGURES AND RESULTS OF PIRAEUS BANK 78 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS AS AT 31 DECEMBER 2004 82 DOMESTIC BRANCH NETWORK 86 DOMESTIC SUBSIDIARIES 93 NETWORK OF BRANCHES AND SUBSIDIARIES ABROAD 94 PiraeusUK_1_26.qxd 13/04/05 14:39 “ Æ2 BRIEF OVERVIEW 1916 ñ Establishment of Piraeus Bank 1918 ñ The shares of Piraeus Bank were listed in the Athens Stock Exchange 1963 ñ Piraeus Bank was integrated into Emporiki Bank Group in Greece 1975 ñ Piraeus Bank came under state control within Emporiki Bank Group 1991 ñ Privatisation of Piraeus Bank 1992 ñ Year of restructuring, reform and growth ñ Participation in Private Investment SA, which was renamed Piraeus Investment -

Social Innovation in an Era of Socio-Spatial Transformations

“Social innovation in an era of socio-spatial transformations. Choosing between responsibility and solidarity” Triantafyllopoulou Eleni *, Poulios Dimitris **, Sayas John*** © by the author(s) (*), Humboldt University of Berlin, National Technical University of Athens (NTUA) Address: Ionon 33-35 Athens, 11851, E - Mail: [email protected] (**)National Technical University of Athens (NTUA), Department of Geography and Regional Planning Address: Pavsaniou 8 Athens, 11635, E- Mail: [email protected] (***) National Technical University of Athens (NTUA), Department of Geography and Regional Planning Address: Iroon Polytechneiou 9 Zografou, 15780 E- Mail: [email protected] Paper presented at the RC21 International Conference on “The Ideal City: between myth and reality. Representations, policies, contradictions and challenges for tomorrow's urban life” Urbino (Italy) 27-29 August 2015. http://www.rc21.org/en/conferences/urbino2015/ 1 Abstract The aim of the paper is to identify the impacts of the collapsing welfare state provisions in Athens, after five years of all-embracing socioeconomic and spatial measures. The rapidly increasing numbers of the unemployed and of persons under poverty level have altered Athens’ social landscape, while the austerity policies promoted have intensified economic inequality, social exclusion and socio-spatial segregation. During this period many local initiatives emerged in the neighbourhoods of the Greek capital in order to find a collective path of dealing with the social repercussions of the crisis. Adopting the slogan ‘no one alone facing crisis’, several grassroot neighbourhood movements, public assemblies and other local initiatives have tried to establish solidarity networks in an attempt to address the on-going survival problems that the majority of the society faces.