Persistent Political Engagement: Social Interactions and the Dynamics of Protest Movements

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reviewing and Evaluating the Direct Elections to the Legislative Council and the Transformation of Political Parties in Hong Kong, 1991-2016

Journal of US-China Public Administration, August 2016, Vol. 13, No. 8, 499-517 doi: 10.17265/1548-6591/2016.08.001 D DAVID PUBLISHING Reviewing and Evaluating the Direct Elections to the Legislative Council and the Transformation of Political Parties in Hong Kong, 1991-2016 Chung Fun Steven Hung The Education University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong After direct elections were instituted in Hong Kong, politicization inevitably followed democratization. This paper intends to evaluate how political parties’ politics happened in Hong Kong’s recent history. The research was conducted through historical comparative analysis, with the context of Hong Kong during the sovereignty transition and the interim period of democratization being crucial. For the implementation of “one country, two systems”, political democratization was hindered and distinct political scenarios of Hong Kong’s transformation were made. The democratic forces had no alternative but to seek more radicalized politics, which caused a decisive fragmentation of the local political parties where the establishment camp was inevitable and the democratic blocs were split into many more small groups individually. It is harmful. It is not conducive to unity and for the common interests of the publics. This paper explores and evaluates the political history of Hong Kong and the ways in which the limited democratization hinders the progress of Hong Kong’s transformation. Keywords: election politics, historical comparative, ruling, democratization The democratizing element of the Hong Kong political system was bounded within the Legislative Council under the principle of the separation of powers of the three governing branches, Executive, Legislative, and Judicial. Popular elections for the Hong Kong legislature were introduced and implemented for 25 years (1991-2016) and there were eight terms of general elections for the Legislative Council. -

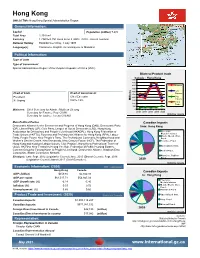

Hong Kong Official Title: Hong Kong Special Administration Region General Information

Hong Kong Official Title: Hong Kong Special Administration Region General Information: Capital Population (million) 7.474n/a Total Area 1,104 km² Currency 1 CAN$=5.791 Hong Kong $ (HKD) (2020 - Annual average) National Holiday Establishment Day, 1 July 1997 Language(s) Cantonese, English, increasing use of Mandarin Political Information: Type of State Type of Government Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China (PRC). Bilateral Product trade Canada - Hong Kong 5000 4500 4000 Balance 3500 3000 Can. Head of State Head of Government Exports 2500 President Chief Executive 2000 Can. Imports XI Jinping Carrie Lam Millions 1500 Total 1000 Trade 500 Ministers: Chief Secretary for Admin.: Matthew Cheung 0 Secretary for Finance: Paul CHAN 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 Statistics Canada Secretary for Justice: Teresa CHENG Main Political Parties Canadian Imports Democratic Alliance for the Betterment and Progress of Hong Kong (DAB), Democratic Party from: Hong Kong (DP), Liberal Party (LP), Civic Party, League of Social Democrats (LSD), Hong Kong Association for Democracy and People’s Livelihood (HKADPL), Hong Kong Federation of Precio us M etals/ stones Trade Unions (HKFTU), Business and Professionals Alliance for Hong Kong (BPA), Labour M ach. M ech. Elec. Party, People Power, New People’s Party, The Professional Commons, Neighbourhood and Prod. Worker’s Service Centre, Neo Democrats, New Century Forum (NCF), The Federation of Textiles Prod. Hong Kong and Kowloon Labour Unions, Civic Passion, Hong Kong Professional Teachers' Union, HK First, New Territories Heung Yee Kuk, Federation of Public Housing Estates, Specialized Inst. Concern Group for Tseung Kwan O People's Livelihood, Democratic Alliance, Kowloon East Food Prod. -

Dissenting Media in Post-1997 Hong Kong Joyce Y.M. Nip the De

Dissenting media in post-1997 Hong Kong Joyce Y.M. Nip The de-colonization of Hong Kong took the form of Britain returning the territory to China in 1997 as a Special Administrative Region (SAR). Twenty years after the political handover, the “one country, two systems” arrangement designed by China to govern the Hong Kong SAR is facing serious challenge: Many in Hong Kong have come to regard Beijing as an unwelcome control master; and calls for self-determination have gained a substantial level of popular support. This chapter examines the role of media in this development, as exemplified by key political protest actions. It proposes the notion of “dissenting media” as a framework to integrate relevant academic and journalistic studies about Hong Kong. From the discipline of media and communications study, it suggests that operators of dissenting media are enabled to put forth information and analysis contrary to that of the establishment, which, in turn, help to form an oppositional public sphere. In the process, the identity and communities of dissent are built, maintained, and developed, contributing to the formation of a counter public that participates in oppositional political actions. Studies on the impact of media, mainly conducted in stable Anglo-American societies, tend to consider mainstream media as institutions that index1 or reinforce the status quo,2 and alternative media as forces that challenge established powers.3 In Hong Kong, the 1997 political changeover was accompanied by a reconfiguration of power relationships in line with China’s one-party dictatorship. The change runs counter to the political aspirations of the people of Hong Kong, and has bred a political movement for civil liberties, public accountability, and democracy. -

Civic Party (Cp)

立法會 CB(2)1335/17-18(04)號文件 LC Paper No. CB(2)1335/17-18(04) CIVIC PARTY (CP) Submission to the United Nations UNIVERSAL PERIODIC REVIEW Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR) CHINA 31st session of the UPR Working Group of the Human Rights Council November 2018 Introduction 1. We are making a stakeholder’s submission in our capacity as a political party of the pro-democracy camp in Hong Kong for the 2018 Universal Periodic Review on the People's Republic of China (PRC), and in particular, the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR). Currently, our party has five members elected to the Hong Kong Legislative Council, the unicameral legislature of HKSAR. 2. In the Universal Periodic Reviews of PRC in 2009 and 2013, not much attention was paid to the human rights, political, and social developments in the HKSAR, whilst some positive comments were reported on the HKSAR situation. i We wish to highlight that there have been substantial changes to the actual implementation of human rights in Hong Kong since the last reviews, which should be pinpointed for assessment in this Universal Periodic Review. In particular, as a pro-democracy political party with members in public office at the Legislative Council (LegCo), we wish to draw the Council’s attention to issues related to the political structure, election methods and operations, and the exercise of freedom and rights within and outside the Legislative Council in HKSAR. Most notably, recent incidents demonstrate that the PRC and HKSAR authorities have not addressed recommendations made by the Human Rights Committee in previous concluding observations in assessing the implementation of International Convention on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR). -

View This Page

14 書香人生 B O O K S & R E V I E W S SUNDAY, APRIL 18, 2010 • TAIPEI TIMES Hardcover: US CDs Taiwan BY DAVid CHen AND Andrew C.C. HuanG Have no illusions STAFF REPORTER AND CONTRIBUTING REPORTER ‘Courtesans and Opium’ is a salacious story masquerading as a cautionary tale BY BRADLEY WINTERTON CONTRIBUTING REPORTER his classic novel’s Chinese name means “romantic illusions,” PUBLICATION NOTES Tbut the academic publishers of this new translation probably hope to catch the eye of a wider public than mere scholars with their more sensational title. It was written by someone who called himself only The Fool of Yangzhou and is dated 1848. Its first known publication was in Jane Zhang (張靚穎) The Hindsight (光景消逝) The DoLittles Fire Ex (滅火器) 1883, though for all anyone knows it Believe in Jane (我相信) From Dripping Tears, He Saw Hopes Earthquakes Standing Here (海上的人) may have been published previously in Universal Music (在眼淚中看見希望) Self-released Uloud Music another, lost edition. Uloud Music It’s about the brothels of Yangzhou, their residents and their patrons. It pre-dates two other remarkable East Asian novels on the same theme, Nagai Kafu’s Rivalry: A Geisha’s Tale [reviewed in Taipei Times March 2, 2008] and The Sing-song Girls of Shanghai by Han Banqing [reviewed in Taipei Times June 22, 2008]. COURTESANS AND OPIUM The semi-anonymous author claims in a brief preface that he’d TRANSLATED BY PATRICK HANAN spent 30 years and all his money on 328 PAGES the spurious pleasures of “false love hile China’s Super Girl of a pipa (琵琶). -

Extensions of Remarks E945 EXTENSIONS of REMARKS

June 1, 2012 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks E945 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS RECOGNIZING THE NORTHERN PRENATAL NONDISCRIMINATION IN RECOGNITION OF EVAN R. HIGH SCHOOL PATRIOTS ACT (PRENDA) OF 2012 CORNS UPON RECEIVING THE HERMAN ‘‘RUSTY’’ SHIPPS LEAD- ERSHIP AWARD HON. STENY H. HOYER SPEECH OF OF MARYLAND HON. BETTY McCOLLUM HON. PATRICK J. TIBERI OF OHIO IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES OF MINNESOTA IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Friday, June 1, 2012 IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Friday, June 1, 2012 Mr. HOYER. Mr. Speaker, I rise today to Wednesday, May 30, 2012 Mr. TIBERI. Mr. Speaker, I rise in recogni- honor and congratulate an extraordinary team tion of Evan R. Corns upon him receiving the Ms. MCCOLLUM. Mr. Speaker, I rise today of young women from Maryland’s fifth con- Herman ‘‘Rusty’’ Shipps leadership award. in opposition to the Prenatal Nondiscrimination This prestigious award is named in honor of gressional district. The Northern High School Act, PRENDA, of 2012 (H.R. 3541). Rusty Shipps, Class of 1913. The Award, be- Patriots won the 3A Maryland ‘‘state softball Every Member of the House opposes the stowed by the Ohio Wesleyan Alumni Board of finals on May 26, 2012. This is their fifth con- Directors, recognizes exemplary leadership, secutive softball state championship and ninth abhorrent practice of gender selection, includ- ing me. In Minnesota, prohibiting sex-selective stewardship, dedication, and commitment to softball championship overall. This incredible the advancement of the university. abortions has passed on a bipartisan basis in achievement was made all the more signifi- Mr. Corns’ support of his alma mater is leg- cant given the caliber of their competition. -

081216-Keast-YAIA-HK

Hong Kong’s disaffected youths – Is the criticism warranted? December 7, 2016 Jacinta Keast Sixtus ‘Baggio’ Leung and Yau Wai-ching, two young legislators from the localist Youngspiration party, have been barred from Hong Kong’s legislative council (LegCo). Never has China’s National People’s Congress (NPC) jumped to an interpretation on a matter in Hong Kong without a prior request from the local government or courts. This comes after the pair modified their oaths, including enunciating the word ‘China’ as ‘Cheena’ (支那), a derogatory term used by the Japanese in World War II, using expletives to refer to the People’s Republic of China, and waving around blue ‘Hong Kong is not China’ banners at their swearing in. Commentators, including those from the pan-democratic side of the legislature, have called their behaviour infantile, ignorant and thuggish, and have demanded ‘that the hooligans be locked up’. But is this criticism warranted? A growing tide of anti-Mainlander vitriol has been building in Hong Kong since it was handed back to the People’s Republic of China in 1997 under a special constitution termed The Basic Law. In theory, the constitution gave Hong Kong special privileges the Mainland did not enjoy—a policy called ‘One Country, Two Systems’. But in practice, more and more Hong Kong residents feel that the long arm of Beijing’s soft power is extending over the territory. The Occupy movement and later the 2014 Umbrella Revolution began once it was revealed that the Chinese government would be pre-screening candidates for the 2017 Hong Kong Chief Executive election, the election for Hong Kong’s top official. -

Rival Securitising Attempts in the Democratisation of Hong Kong Written by Neville Chi Hang Li

Rival Securitising Attempts in the Democratisation of Hong Kong Written by Neville Chi Hang Li This PDF is auto-generated for reference only. As such, it may contain some conversion errors and/or missing information. For all formal use please refer to the official version on the website, as linked below. Rival Securitising Attempts in the Democratisation of Hong Kong https://www.e-ir.info/2019/03/29/rival-securitising-attempts-in-the-democratisation-of-hong-kong/ NEVILLE CHI HANG LI, MAR 29 2019 This is an excerpt from New Perspectives on China’s Relations with the World: National, Transnational and International. Get your free copy here. The principle of “one country, two systems” is in grave political danger. According to the Joint Declaration on the Question of Hong Kong signed in 1984, and as later specified in Article 5 of the Basic Law, i.e. the mini-constitution of Hong Kong, the capitalist system and way of life in Hong Kong should remain unchanged for 50 years. This promise not only settled the doubts of the Hong Kong people in the 1980s, but also resolved the confidence crisis of the international community due to the differences in the political and economic systems between Hong Kong and the People’s Republic of China (PRC). As stated in the record of a meeting between Thatcher and Deng in 1982, the Prime Minister regarded the question of Hong Kong as an ‘immediate issue’ as ‘money and skill would immediately begin to leave’ if such political differences were not addressed (Margaret Thatcher Foundation 1982). -

2012 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ELECTION NOMINATIONS for GEOGRAPHICAL CONSTITUENCIES (NOMINATION PERIOD: 18-31 JULY 2012) As at 5Pm, 26 July 2012 (Thursday)

2012 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ELECTION NOMINATIONS FOR GEOGRAPHICAL CONSTITUENCIES (NOMINATION PERIOD: 18-31 JULY 2012) As at 5pm, 26 July 2012 (Thursday) Geographical Date of List (Surname First) Alias Gender Occupation Political Affiliation Remarks Constituency Nomination Hong Kong Island SIN Chung-kai M Politician The Democratic Party 18/7/2012 YEUNG Sum M The Honorary Assistant Professor The Democratic Party 18/7/2012 CHAI Man-hon M District Council Member The Democratic Party 18/7/2012 CHENG Lai-king F Registered Social Worker The Democratic Party 18/7/2012 LEUNG Suk-ching F District Council Member The Democratic Party 18/7/2012 HUI Chi-fung M District Council Member The Democratic Party 18/7/2012 Hong Kong Island HUI Ching-on M Legal and Financial Consultant 18/7/2012 Hong Kong Island IP LAU Suk-yee Regina F Chairperson/Board of Governors New People's Party 18/7/2012 WONG Chor-fung M Public Policy Researcher New People's Party 18/7/2012 TSE Tsz-kei M Community Development Officer New People's Party 18/7/2012 Hong Kong Island LAU Kin-yee Miriam F Solicitor Liberal Party 18/7/2012 SHIU Ka-fai M Managing Director Liberal Party 18/7/2012 LEE Chun-keung Michael M Manager Liberal Party 18/7/2012 Hong Kong Island LO Wing-lok M Medical Practitioner 18/7/2012 Hong Kong Island LAU Gar-hung Christopher M Retirement Benefits Consultant People Power 18/7/2012 SHIU Yeuk-yuen M Company Director 18/7/2012 AU YEUNG Ying-kit Jeff M Family Doctor 18/7/2012 Hong Kong Island CHUNG Shu-kun Christopher Chris M Full-time District Councillor Democratic Alliance -

Thrf-2019-1-Winners-V3.Pdf

TO ALL 21,100 Congratulations WINNERS Home Lottery #M13575 JohnDion Bilske Smith (#888888) JohnGeoff SmithDawes (#888888) You’ve(#105858) won a 2019 You’ve(#018199) won a 2019 BMWYou’ve X4 won a 2019 BMW X4 BMWYou’ve X4 won a 2019 BMW X4 KymJohn Tuck Smith (#121988) (#888888) JohnGraham Smith Harrison (#888888) JohnSheree Smith Horton (#888888) You’ve won the Grand Prize Home You’ve(#133706) won a 2019 You’ve(#044489) won a 2019 in Brighton and $1 Million Cash BMWYou’ve X4 won a 2019 BMW X4 BMWYou’ve X4 won a 2019 BMW X4 GaryJohn PeacockSmith (#888888) (#119766) JohnBethany Smith Overall (#888888) JohnChristopher Smith (#888888)Rehn You’ve won a 2019 Porsche Cayenne, You’ve(#110522) won a 2019 You’ve(#132843) won a 2019 trip for 2 to Bora Bora and $250,000 Cash! BMWYou’ve X4 won a 2019 BMW X4 BMWYou’ve X4 won a 2019 BMW X4 Holiday for Life #M13577 Cash Calendar #M13576 Richard Newson Simon Armstrong (#391397) Win(#556520) a You’ve won $200,000 in the Cash Calendar You’ve won 25 years of TICKETS Win big TICKETS holidayHolidays or $300,000 Cash STILL in$15,000 our in the Cash Cash Calendar 453321 Annette Papadulis; Dernancourt STILL every year AVAILABLE 383643 David Allan; Woodville Park 378834 Tania Seal; Wudinna AVAILABLE Calendar!373433 Graeme Blyth; Para Hills 428470 Vipul Sharma; Mawson Lakes for 25 years! 361598 Dianne Briske; Modbury Heights 307307 Peter Siatis; North Plympton 449940 Kate Brown; Hampton 409669 Victor Sigre; Henley Beach South 371447 Darryn Burdett; Hindmarsh Valley 414915 Cooper Stewart; Woodcroft 375191 Lynette Burrows; Glenelg North 450101 Filomena Tibaldi; Marden 398275 Stuart Davis; Hallett Cove 312911 Gaynor Trezona; Hallett Cove 418836 Deidre Mason; Noarlunga South 321163 Steven Vacca; Campbelltown 25 years of Holidays or $300,000 Cash $200,000 in the Cash Calendar Winner to be announced 29th March 2019 Winners to be announced 29th March 2019 Finding cures and improving care Date of Issue Home Lottery Licence #M13575 2729 FebruaryMarch 2019 2019 Cash Calendar Licence ##M13576M13576 in South Australia’s Hospitals. -

Chapter 6 Hong Kong

CHAPTER 6 HONG KONG Key Findings • The Hong Kong government’s proposal of a bill that would allow for extraditions to mainland China sparked the territory’s worst political crisis since its 1997 handover to the Mainland from the United Kingdom. China’s encroachment on Hong Kong’s auton- omy and its suppression of prodemocracy voices in recent years have fueled opposition, with many protesters now seeing the current demonstrations as Hong Kong’s last stand to preserve its freedoms. Protesters voiced five demands: (1) formal with- drawal of the bill; (2) establishing an independent inquiry into police brutality; (3) removing the designation of the protests as “riots;” (4) releasing all those arrested during the movement; and (5) instituting universal suffrage. • After unprecedented protests against the extradition bill, Hong Kong Chief Executive Carrie Lam suspended the measure in June 2019, dealing a blow to Beijing which had backed the legislation and crippling her political agenda. Her promise in September to formally withdraw the bill came after months of protests and escalation by the Hong Kong police seeking to quell demonstrations. The Hong Kong police used increasingly aggressive tactics against protesters, resulting in calls for an independent inquiry into police abuses. • Despite millions of demonstrators—spanning ages, religions, and professions—taking to the streets in largely peaceful pro- test, the Lam Administration continues to align itself with Bei- jing and only conceded to one of the five protester demands. In an attempt to conflate the bolder actions of a few with the largely peaceful protests, Chinese officials have compared the movement to “terrorism” and a “color revolution,” and have im- plicitly threatened to deploy its security forces from outside Hong Kong to suppress the demonstrations. -

September 2013

Issue 1- September 2013 Badger Girls State Badger Boys By Rutvi Shah State By Jeremy Gartland This past summer Monika Ford Politics, leadership, sports, and I had the opportunity to represent and community. Combined, JMM at UW-Oshkosh for a program these things begin to describe the Controversal Bill... page 2 called Badger Girls State. Girls unique experience of Badger Boys The News You missed?... page 3 State is a nationwide leadership and State. A week-long government Sports... page 4 citizenship program for high school simulation sponsored by American Advice to Freshman... page 5 juniors. Delegates have the chance Legion, Badger Boys State (BBS) Entertainment... page 6 to learn about local and state govern- draws high school juniors from ments when they run for offices at across the state to participate in city, county, and state levels. The first what for many is a life-changing few days were overwhelming, but the experience was definitely worth event. it in the end! At city meetings Badger citizens decided how their cities Pulling up to Ripon College, the site of BBS since would function. Badger girls ran for various positions and they intro- its creation, I didn’t recognize duced obnoxious ordinances; for instance, the citizens of Willow Springs campaigns, law-making, and even a single face in the crowd nuclear catastrophes. After a day of made it mandatory for everyone to yell “duck and cover” when “poten- of my peers. What was also tially dangerous males” were present. getting to know my fellow citizens, clear was that no one else did I had the privilege of being elected One of the highlights of the week was attending the Badger Girls State either.