Volume 11, Spring 2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Filumena and the Canadian Identity a Research Into the Essence of Canadian Opera

Filumena and The Canadian Identity A Research into the Essence of Canadian Opera Alexandria Scout Parks Final thesis for the Bmus-program Icelandic Academy of the Arts Music department May 2020 Filumena and The Canadian Identity A Research into the Essence of Canadian Opera Alexandria Scout Parks Final Thesis for the Bmus-program Supervisor: Atli Ingólfsson Music Department May 2020 This thesis is a 6 ECTS final thesis for the B.Mus program. You may not copy this thesis in any way without consent from the author. Abstract In this thesis I sought to identify the essence of Canadian opera and to explore how the opera Filumena exemplifies that essence. My goal was to first establish what is unique about Canadian opera. To do this, I started by looking into the history of opera composition and performance in Canada. By tracing these two interlocking histories, I was able to gather a sense of the major bodies of work within the Canadian opera repertoire. I was, as well, able to deeper understand the evolution, and at some points, stagnation of Canadian opera by examining major contributing factors within this history. My next steps were to identify trends that arose within the history of opera composition in Canada. A closer look at many of the major works allowed me to see the similarities in terms of things such as subject matter. An important trend that I intend to explain further is the use of Canadian subject matter as the basis of the operas’ narratives. This telling of Canadian stories is one aspect unique to Canadian opera. -

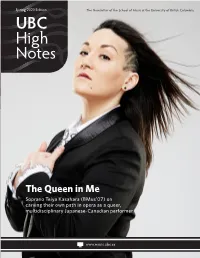

Spring 2020 Edition the Newsletter of the School of Music at the University of British Columbia UBC High Notes

Spring 2020 Edition The Newsletter of the School of Music at the University of British Columbia UBC High Notes The Queen in Me Soprano Teiya Kasahara (BMus’07) on carving their own path in opera as a queer, multidisciplinary Japanese-Canadian performer www.music.ubc.ca SPOTLIGHT LIBERATING THE QUEEN IN ME Photo: Takumi Hayashi/UBC In their new play The Queen in Me, soprano Teiya Kasahara (BMus’07) liberates one of opera’s most iconic villains — and challenges the industry’s centuries-old prejudices Photo: Tallulah By Tze Liew In The Queen in Me, the Queen of the Night at age 15, after seeing Ingmar Bergman’s film begins to sing her most iconic aria, “Der Hölle version of The Magic Flute. “I saw her perform For more than two centuries, the iconic Queen Rache,” like she would in any Magic Flute show. and was like, Oh God, I want to do that,” they of the Night from Mozart’s Die Zauberflöte But midway through, she halts. “Stopp! Stopp remember. has been thrilling audiences with her vengeful die Musik!” she screams. Breaking the fourth spirit, bloodthirsty drive, and volatile high Fs. wall, she laments the stifling act everyone’s With this as their dream role, Kasahara dove Qualities that make her the ultimate villain, come to see; one she’s been trapped in for headfirst into voice training, made it into fated to eternal doom while the hero and over two centuries. the UBC Opera program, and honed their heroine, demure as lambs, skip off to enjoy craft for four years under the tutelage of their happy ending. -

October 8, 1982 Concert Program

NEW MUSIC CONCERTS 1982-83 CONTEMPORARY ENCOUNTERS. CANADIAN MUSIC. GOOD MUSIC. On Sale now from the Canadian Music Centre are: CMC 1 Canadian Electronic Ensemble. Music composed and performed by Grimes, Jaeger, Lake and Montgomery. CMC 0281 Spectra - The Elmer Iseler Singers. Choral music by Ford, Morawetz and Somers. CMC 0382 Sonics - Antonin Kubalek. Piano solo music by Anhalt, Buczynski and Dolin. CMC 0682 Washington Square - The London Symphony Orchestra. Ballet music by Michael Conway Baker. CMC 0582 ‘Private Collection - Philip Candelaria, Mary Lou Fallis, Monica Gaylord. The music of John Weinzweig. CMC 0482 Folia - Available October 1, 1982. Wind quintet music by Cherney, Hambraeus, Sherman and Aitken, performed by the York Winds. In production: Orders accepted now: CMC 0782 2x4- The Purcell String Quartet. Music by Pentland and Somers. CMC 0883 Viola Nouveau - Rivka Golani-Erdesz. Music by Barnes, Joachim, Prévost, Jaeger and Cherney. Write or phone to place orders, or for further information contact: The Canadian Music Centre 1263 Bay Street Toronto, Ontario MSR 2C!1 (416) 961-6601 NEW MUSIC CONCERTS Robert Aitken Artistic Director presents COMPOSERS: HARRY FREEDMAN LUKAS FOSS ALEXINA LOUIE BARBARA PENTLAND GUEST SOLOISTS: ERICA GOODMAN BEVERLEY JOHNSTON MARY MORRISON JOSEPH MACEROLLO October 8, 1982 8:30 P.M. Walter Hall, Edward Johnson Building, University of Toronto EER IONG..R AM REFUGE (1981) ALEXINA LOUIE JOSEPH MACEROLLO, accordion ERICA GOODMAN, harp BEVERLEY JOHNSTON, vibraphone COMMENTA (1981) BARBARA PENTLAND ERICA -

Alexina Louie's Music, As Demonstrated in Example 4, the Third Movement of Starsrruck, Berceuse Des Étoiles

UNIVERSITY OF ALBERTA ON THE MUSICAL SILK ROUTE: PIANO MUSIC OF ALEXINA LOUE An essay submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Music DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC EDMONTON, ALBERTA SPRING 1997 Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibiiographic Servicas - semsbiMiographiques The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accorde une iicence non exclusive licence ailowing the excluSm permettant à la National LiIbrary of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, disniute or seïi reproduire, prêter, distri%uerou copies of Merthesis by any means vendre des copies de sa thèse de and in any form or format, mahg quelque manière et sous quelque this thesis available to interested forme que ce soit pour mettre des persons. exemplaires de cette thèse a la disposition des personnes intéressées. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in hismer thesis. Ncither &oit d'auteur qui protège sa thèse. Ni the thesis nor substantial extracts la thèse ni des extraits substantiels de f?om it may be p~tedor othewise celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés ou reproduced with the author's autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. TO JESUS AND MY FAMLLY Abstract One of seved outstanding stylistic elements of Alexina Louie's piano music is her extensive use of imaginative figurations. This particular kind of gesture derives from Louie's experience with the Japanese Gagaku ensemble and with the Chinese stringed instrument calIed the ch'in--an experience that wt only infiuences the shape of figurations on the printed page, but also shapes the player's mental and spiritual expedences during the performance of her music. -

Download the TSO Commissions History

Commissions Première Composer Title They do not shimmer like the dry grasses on the hills, or January 16, 2019 Emilie LeBel the leaves on the trees March 10, 2018 Gary Kulesha Double Concerto January 25, 2018 John Estacio Trumpet Concerto [co-commission] In Excelsis Gloria (After the Huron Carol): Sesquie for December 12, 2017 John McPherson Canada’s 150th [co-commmission] The Talk of the Town: Sesquie for Canada’s 150th December 6, 2017 Andrew Ager [co-commission] December 5, 2017 Laura Pettigrew Dòchas: Sesquie for Canada’s 150th [co-commission] November 25, 2017 Abigail Richardson-Schulte Sesquie for Canada’s 150th (interim title) [co-commission] Just Keep Paddling: Sesquie for Canada’s 150th November 23, 2017 Tobin Stokes [co-commission] November 11, 2017 Jordan Pal Sesquie for Canada’s 150th (interim title) [co-commission] November 9, 2017 Julien Bilodeau Sesquie for Canada’s 150th (interim title) [co-commission] November 3, 2017 Daniel Janke Small Song: Sesquie for Canada’s 150th [co-commission] October 21, 2017 Nicolas Gilbert UP!: Sesquie for Canada’s 150th [co-commission] Howard Shore/text by October 19, 2017 New Work for Mezzo-soprano and Orchestra Elizabeth Cottnoir October 19, 2017 John Abram Start: Sesquie for Canada’s 150th [co-commission] October 7, 2017 Eliot Britton Adizokan October 7, 2017 Carmen Braden Blood Echo: Sesquie for Canada’s 150th [co-commission] October 3, 2017 Darren Fung Toboggan!: Sesquie for Canada’s 150th [co-commission] Buzzer Beater: Sesquie for Canada’s 150th September 28, 2017 Jared Miller [co-commission] -

National Arts Centre Orchestra 2004-2005

NATIONAL ARTS CENTRE 04 ORCHESTRA SEASON PINCHAS ZUKERMAN 05 MUSIC DIRECTOR “RICH, LUSTROUS SOUND...” NEW YORK TIMES SUBSCRIBE NOW! www.nac-cna.ca 1.866.850.ARTS 613.947.7000 ext. 620 Dear Friends, I would like to welcome you all to the 2004-2005 National Arts Centre Orchestra season. I am delighted to be back in Ottawa and am looking forward to a season of great music and variety. Thank you to all our patrons, particularly our subscribers, for your loyalty, dedication and continued support of our great Orchestra. As you will see from this brochure, the 04-05 season holds much in store, from Beethoven to Elgar to Sibelius. I will also be making my NAC Pops Series debut playing some of the music I loved to hear Isaac Stern perform. Join us in Southam Hall for a season of wonderful music and great fun. Pinchas Zukerman Music Director SIGNATURE SERIES CONCERTS BEGIN AT 20:00 IN SOUTHAM HALL. JON KIMURA PARKER ILYA GRINGOLTS HUBBARD STREET DANCE PINCHAS ZUKERMAN JONATHAN BISS YEFIM BRONFMAN CHICAGO SPONSORED SEPTEMBER 22-23, 2004 TCHAIKOVSKY 1 BY PINCHAS ZUKERMAN conductor Piano Concerto No. WEDNESDAY-THURSDAY JON KIMURA PARKER piano in B-flat minor, Op. 23 RACHMANINOV Symphony No. 2 in E minor, Op. 27 OCTOBER 27-28, 2004 JEFFREY KAHANE conductor and piano HAYDN Symphony No. 102 in B-flat major WEDNESDAY-THURSDAY ILYA GRINGOLTS violin PROKOFIEV Violin Concerto No. 1 in D major, Op. 19 MOZART Piano Concerto No. 27, in B-flat major, K. 595 JANUARY 12-13, 2005 PINCHAS ZUKERMAN J.S. -

Jules Léger Prize | Prix Jules-Léger

Jules Léger Prize | Prix Jules-Léger Year/Année Laureates/Lauréats 2020 Kelly-Marie Murphy (Ottawa, ON) Coffee Will be Served in the Living Room (2018) 2019 Alec Hall (New York, NY) Vertigo (2018) 2018 Brian Current (Toronto, ON) Shout, Sisyphus, Flock 2017 Gabriel Turgeon-Dharmoo (Montréal, QC) Wanmansho 2016 Cassandra Miller (Victoria, BC) About Bach 2015 2015 Pierre Tremblay (Huddersfield, UK) Les pâleurs de la lune (2013-14) 2014 Thierry Tidrow (Ottawa, ON) Au fond du Cloître humide 2013 Nicole Lizée (Lachine, QC) White Label Experiment 2012 Zosha Di Castri (New York, NY) Cortège 2011 Cassandra Miller (Montréal, QC) Bel Canto 2010 Justin Christensen (Langley, BC) The Failures of Marsyas 2009 Jimmie LeBlanc (Brossard, QC) L’Espace intérieur du monde 2008 Analia Llugdar (Montréal, QC) Que sommes-nous 2007 Chris Paul Harman (Montréal, QC) Postludio a rovescio 2006 James Rolfe (Toronto, ON) raW 2005 Linda Catlin Smith (Toronto, ON) Garland 2004 Patrick Saint-Denis (Charlebourg, QC) Les dits de Victoire 2003 Éric Morin (Québec, QC) D’un château l’autre 2002 Yannick Plamondon, (Québec, QC) Autoportrait sur Times Square 2001 Chris Paul Harman (Toronto, ON) Amerika Canada Council for the Arts | Conseil des arts du Canada 1-800-263-5588 | canadacouncil.ca | conseildesarts.ca 2000 André Ristic (Montréal, QC) Catalogue 1 (bombes occidentales) 1999 Alexina Louie (Toronto, ON) Nightfall 1998 Michael Oesterle (Montréal, QC) Reprise 1997 Omar Daniel (Toronto, ON) Zwei Lieder nach Rilke 1996 Christos Hatzis (Toronto, ON) Erotikos Logos 1995 John Burke (Toronto, ON) String Quartet 1994 Peter Paul Koprowski (London, ON) Woodwind Quintet 1993 Bruce Mather (Montréal, QC) YQUEM 1992 John Rea (Outremont, QC) Objets perdus 1991 Donald Steven (Montréal, QC) In the Land of Pure Delight 1989 Peter Paul Koprowski (London, ON) Sonnet for Laura 1988 Michael Colgrass (Toronto, ON) Strangers: Irreconcilable Variations for Clarinet, Viola and Piano 1987 Denys Bouliane (Montréal, QC) À propos.. -

Œuvres CANADIENNES Canadian Works

œuvres CANADIENNES Canadian Works ZOSHA DI CASTRI JACQUES HÉTU NICOLE LIZÉE ALEXINA LOUIE SAMY MOUSSA MATTHEW RICKETTS ANA SOKOLOVIĆ CLAUDE VIVIER Sur la scène culturelle canadienne, les compositeurs occupent un espace de création d’une grande effervescence et ils reçoivent régulièrement des commandes des principaux ensembles du Canada et d’ailleurs. L’OSM vous encourage à explorer la richesse et la diversité du répertoire de musique canadienne disponible pour consultation et location au Centre de musique canadienne, lequel représente 700 compositeurs agréés d’hier et d’aujourd’hui, et quelque 18 000 œuvres. www.musiccentre.ca/fr Canadian composers are part of a vibrant and active creative scene, and are regularly commissioned by major ensembles in Canada and abroad. The OSM encourages you to explore the rich and ORCHESTRE Bergeron ©Pierre-Étienne diverse repertoire of Canadian music available for consultation and rental at the Canadian Music Centre, representing over 700 associate composers past and SYMPHONIQUE present, and some 18,000 works. www.musiccentre.ca DE MONTRÉAL À l’Orchestre symphonique de Montréal, nous croyons profondément en la promotion et en la valorisation des compositeurs canadiens et de leurs œuvres. Ainsi, nous avons dressé une liste de compositeurs et d’œuvres qui mettent en relief la richesse de la création musicale contemporaine au Canada. Bien que non exhaustive, cette sélection témoigne néanmoins de notre solide conviction quant à l’importance des œuvres canadiennes pour notre propre culture et pour le patrimoine de la culture musicale universelle. Elle souligne également les efforts constants POUR DE PLUS AMPLES RENSEIGNEMENTS de l’OSM pour célébrer les artistes canadiens et diffuser leurs créations. -

AMERICAN CLASSICS George CRUMB Vox Balaenae

559205 bk Crumb US 14/9/06 10:40 Page 8 George AMERICAN CLASSICS CRUMB (b. 1929) George 1 Vox Balaenae (1971) for Three Masked Players 18:50 (Amplified Flute, Amplified Cello, and Amplified Piano) CRUMB Federico’s Little Songs for Children (1986) 13:24 Vox Balaenae 2 1. La Señorita del Abanico (Señorita of the Fan) 2:13 3 2. La Tarde (Afternoon) 1:49 (Voice of the Whale) 4 3. Canción Cantada (A Song Sung) 1:19 5 4. Caracola (Snail) 2:36 New Music Concerts Ensemble • Robert Aitken 6 5. El Lagarto está Llorando! (The Lizard is Crying) 2:06 7 6. Cancioncilla Sevillana (A Little Song from Seville) 1:51 8 7. Canción Tonta (Silly Song) 1:31 9 An Idyll for the Misbegotten (Images III) (1986) 9:51 0 Eleven Echoes of Autumn (Echoes I) (1965) 17:36 for Violin, Alto Flute, Clarinet and Piano This recording was made possible by the generous support of The Herbert Green Family Charitable Foundation Inc. 8.559205 8 559205 bk Crumb US 14/9/06 10:40 Page 2 George Crumb (b. 1929) Ryan Scott Vox Balaenae • Federico’s Little Songs for Children • An Idyll for the Misbegotten • Eleven Echoes of Autumn Ryan Scott is an acclaimed marimba and multi-percussion soloist. He also plays with the Toronto Symphony George Crumb’s reputation as a composer of hauntingly (1977), for soprano, solo trombone, antiphonal Orchestra, the Canadian Opera Company Orchestra, Esprit Orchestra, New Music Concerts, the Composers’ beautiful scores has made him one of the most children’s voices, male speaking choir, bell ringers and Orchestra, the Bob Becker Ensemble, Soundstreams Canada, Continuum, ArpaTambora, and the Evergreen Club. -

The Contribution of Twentieth-Century Canadian Composers to The

THE CONTRIBUTION OF TWENTIETH-CENTURY CANADIAN COMPOSERS TO THE SOLO PEDAL HARP REPERTOIRE, WITH ANALYSIS OF SELECTED WORKS A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE DOCTOR OF ARTS BY GRACE BAUSON APPROVED BY: ____________________________________________ _____________ Ms. Elizabeth Richter, Committee Co-Chairperson Date ___________________________________________ _____________ Dr. Keith Kothman, Committee Co-Chairperson Date ______________________________________________ _____________ Dr. James Helton, Committee Member Date ______________________________________________ _____________ Dr. Michael Oravitz, Committee Member Date ______________________________________________ _____________ Dr. Debra Siela, Committee Member Date ______________________________________________ _____________ Robert Morris, Dean of Graduate School Date BALL STATE UNIVERSITY MUNCIE, INDIANA MAY 2012 Copyright © 2012 by Grace Bauson All rights reserved THE CONTRIBUTION OF TWENTIETH-CENTURY CANADIAN COMPOSERS TO THE SOLO PEDAL HARP REPERTOIRE, WITH ANALYSIS OF SELECTED WORKS A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE DOCTOR OF ARTS BY GRACE BAUSON ADVISOR – MS. ELIZABETH RICHTER BALL STATE UNIVERSITY MUNCIE, INDIANA MAY 2012 ii ABSTRACT DISSERTATION: The Contribution of Twentieth-Century Canadian Composers to the Solo Pedal Harp Repertoire, with Analysis of Selected Works STUDENT: Grace Bauson DEGREE: Doctor of Arts COLLEGE: Fine Arts DATE: May 2012 PAGES: 158 The purpose of this dissertation was to research harp solos written by Canadian composers in the twentieth century and to determine factors that could have contributed to the rise in output of harp literature in Canada during that period. In addition to research of existing writings, interviews with two performers, Erica Goodman and Judy Loman, and two composers, Marjan Mozetich and R. Murray Schafer, were conducted. -

Fusion Process in the Instrumental Works by Chen Yi Xin Guo

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2002 Chinese Musical Language Interpreted by Western Idioms: Fusion Process in the Instrumental Works by Chen Yi Xin Guo Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF MUSIC CHINESE MUSICAL LANGUAGE INTERPRETED BY WESTERN IDIOMS: FUSION PROCESS IN THE INSTRUMENTAL WORKS BY CHEN YI By XIN GUO A Dissertation submitted to the School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2002 The members of the Committee approve the dissertation of Xin Guo defended on November 6, 2002. James Mathes Professor Directing Dissertation Andrew Killick Outside Committee Member Jane Piper Clendinning Committee Member Peter Spencer Committee Member Approved: Seth Beckman, Assistant Dean for Academic Affairs and Director of Graduate Studies, School of Music ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my deepest gratitude to many people who have helped me in one way or another during my research and writing of this dissertation. Dr. Chen Yi’s music inspired me to choose the topic of this project; she provided all the scores, the recordings, and her reference materials for me and responded to my questions in a timely manner during my research. Dr. Richard Bass guided me throughout my master’s thesis, an early stage of this project. His keen insight and rigorous thought influenced my thinking tremendously. Dr. Harris Fairbanks spent countless hours proofreading both my thesis and dissertation. His encouragement and unwavering support helped me enormously and for this I am deeply indebted to him. -

Middle Power Music: Modernism, Ideology, and Compromise in English Canadian Cold War Composition

SSStttooonnnyyy BBBrrrooooookkk UUUnnniiivvveeerrrsssiiitttyyy The official electronic file of this thesis or dissertation is maintained by the University Libraries on behalf of The Graduate School at Stony Brook University. ©©© AAAllllll RRRiiiggghhhtttsss RRReeessseeerrrvvveeeddd bbbyyy AAAuuuttthhhooorrr... Middle Power Music: Modernism, Ideology, and Compromise in English Canadian Cold War Composition A Dissertation Presented by Sarah Christine Emily Hope Feltham to The Graduate School in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music History and Theory Stony Brook University December 2015 Stony Brook University The Graduate School Sarah Christine Emily Hope Feltham We, the dissertation committee for the above candidate for the Doctor of Philosophy degree, hereby recommend acceptance of this dissertation. Dr. Ryan Minor - Dissertation Advisor Associate Professor, Department of Music, Stony Brook University Dr. Sarah Fuller - Chairperson of Defense Professor Emerita, Department of Music, Stony Brook University Dr. Margarethe Adams Assistant Professor, Department of Music, Stony Brook University Dr. Robin Elliott—Outside Reader Professor (Musicology), Jean A. Chalmers Chair in Canadian Music Faculty of Music, University of Toronto This dissertation is accepted by the Graduate School Charles Taber Dean of the Graduate School ii ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Middle Power Music: Modernism, Ideology, and Compromise in English Canadian Cold War Composition by Sarah Feltham Doctor of Philosophy in Music History and Theory Stony Brook University December 2015 This dissertation argues that English Canadian composers of the Cold War period produced works that function as “middle power music.” The concept of middlepowerhood, central to Canadian policy and foreign relations in this period, has been characterized by John W.