ALABAMA University Libraries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Messier Objects

Messier Objects From the Stocker Astroscience Center at Florida International University Miami Florida The Messier Project Main contributors: • Daniel Puentes • Steven Revesz • Bobby Martinez Charles Messier • Gabriel Salazar • Riya Gandhi • Dr. James Webb – Director, Stocker Astroscience center • All images reduced and combined using MIRA image processing software. (Mirametrics) What are Messier Objects? • Messier objects are a list of astronomical sources compiled by Charles Messier, an 18th and early 19th century astronomer. He created a list of distracting objects to avoid while comet hunting. This list now contains over 110 objects, many of which are the most famous astronomical bodies known. The list contains planetary nebula, star clusters, and other galaxies. - Bobby Martinez The Telescope The telescope used to take these images is an Astronomical Consultants and Equipment (ACE) 24- inch (0.61-meter) Ritchey-Chretien reflecting telescope. It has a focal ratio of F6.2 and is supported on a structure independent of the building that houses it. It is equipped with a Finger Lakes 1kx1k CCD camera cooled to -30o C at the Cassegrain focus. It is equipped with dual filter wheels, the first containing UBVRI scientific filters and the second RGBL color filters. Messier 1 Found 6,500 light years away in the constellation of Taurus, the Crab Nebula (known as M1) is a supernova remnant. The original supernova that formed the crab nebula was observed by Chinese, Japanese and Arab astronomers in 1054 AD as an incredibly bright “Guest star” which was visible for over twenty-two months. The supernova that produced the Crab Nebula is thought to have been an evolved star roughly ten times more massive than the Sun. -

Hubble Space Telescope Imaging of Brightest Cluster Galaxies1

Astronomical Journal, accepted for publication HUBBLE SPACE TELESCOPE IMAGING OF BRIGHTEST CLUSTER GALAXIES1 Seppo Laine2, Roeland P. van der Marel Space Telescope Science Institute, 3700 San Martin Drive, Baltimore, MD 21218 Tod R. Lauer National Optical Astronomy Observatories, P.O. Box 26732, Tucson, AZ 85726 Marc Postman, Christopher P. O’Dea Space Telescope Science Institute, 3700 San Martin Drive, Baltimore, MD 21218 and Frazer N. Owen National Radio Astronomy Observatory, P.O. Box O, Socorro, NM 87801 ABSTRACT 1Based on observations made with the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope, obtained at the Space Telescope Science Institute, which is operated by the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy, Inc., under NASA contract NAS 5-26555. These observations are associated with proposal #8683. 2Present address: SIRTF Science Center, California Institute of Technology, 220-6, 1200 East California Boulevard, Pasadena, CA 91125 –2– We used the HST WFPC2 to obtain I-band images of the centers of 81 brightest cluster galaxies (BCGs), drawn from a volume-limited sample of nearby BCGs. The images show a rich variety of morphological features, including multiple or double nuclei, dust, stellar disks, point source nuclei, and central surface brightness depressions. High resolution surface brightness profiles could be inferred for 60 galaxies. Of those, 88% have well-resolved cores. The relationship between core size and galaxy luminosity for BCGs is indistinguishable from that of Faber et al. (1997, hereafter F97) for galaxies within the same luminosity range. However, the core sizes of the most luminous BCGs fall below the extrapolation of the F97 relationship r L1.15. -

Globular Clusters and Galactic Nuclei

Scuola di Dottorato “Vito Volterra” Dottorato di Ricerca in Astronomia– XXIV ciclo Globular Clusters and Galactic Nuclei Thesis submitted to obtain the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (“Dottore di Ricerca”) in Astronomy by Alessandra Mastrobuono Battisti Program Coordinator Thesis Advisor Prof. Roberto Capuzzo Dolcetta Prof. Roberto Capuzzo Dolcetta Anno Accademico 2010-2011 ii Abstract Dynamical evolution plays a key role in shaping the current properties of star clus- ters and star cluster systems. We present the study of stellar dynamics both from a theoretical and numerical point of view. In particular we investigate this topic on different astrophysical scales, from the study of the orbital evolution and the mutual interaction of GCs in the Galactic central region to the evolution of GCs in the larger scale galactic potential. Globular Clusters (GCs), very old and massive star clusters, are ideal objects to explore many aspects of stellar dynamics and to investigate the dynamical and evolutionary mechanisms of their host galaxy. Almost every surveyed galaxy of sufficiently large mass has an associated group of GCs, i.e. a Globular Cluster System (GCS). The first part of this Thesis is devoted to the study of the evolution of GCSs in elliptical galaxies. Basing on the hypothesis that the GCS and stellar halo in a galaxy were born at the same time and, so, with the same density distribution, a logical consequence is that the presently observed difference may be due to evolution of the GCS. Actually, in this scenario, GCSs evolve due to various mechanisms, among which dynamical friction and tidal interaction with the galactic field are the most important. -

The Messier Catalog

The Messier Catalog Messier 1 Messier 2 Messier 3 Messier 4 Messier 5 Crab Nebula globular cluster globular cluster globular cluster globular cluster Messier 6 Messier 7 Messier 8 Messier 9 Messier 10 open cluster open cluster Lagoon Nebula globular cluster globular cluster Butterfly Cluster Ptolemy's Cluster Messier 11 Messier 12 Messier 13 Messier 14 Messier 15 Wild Duck Cluster globular cluster Hercules glob luster globular cluster globular cluster Messier 16 Messier 17 Messier 18 Messier 19 Messier 20 Eagle Nebula The Omega, Swan, open cluster globular cluster Trifid Nebula or Horseshoe Nebula Messier 21 Messier 22 Messier 23 Messier 24 Messier 25 open cluster globular cluster open cluster Milky Way Patch open cluster Messier 26 Messier 27 Messier 28 Messier 29 Messier 30 open cluster Dumbbell Nebula globular cluster open cluster globular cluster Messier 31 Messier 32 Messier 33 Messier 34 Messier 35 Andromeda dwarf Andromeda Galaxy Triangulum Galaxy open cluster open cluster elliptical galaxy Messier 36 Messier 37 Messier 38 Messier 39 Messier 40 open cluster open cluster open cluster open cluster double star Winecke 4 Messier 41 Messier 42/43 Messier 44 Messier 45 Messier 46 open cluster Orion Nebula Praesepe Pleiades open cluster Beehive Cluster Suburu Messier 47 Messier 48 Messier 49 Messier 50 Messier 51 open cluster open cluster elliptical galaxy open cluster Whirlpool Galaxy Messier 52 Messier 53 Messier 54 Messier 55 Messier 56 open cluster globular cluster globular cluster globular cluster globular cluster Messier 57 Messier -

Introduction to Astronomical Photometry, Second Edition

This page intentionally left blank Introduction to Astronomical Photometry, Second Edition Completely updated, this Second Edition gives a broad review of astronomical photometry to provide an understanding of astrophysics from a data-based perspective. It explains the underlying principles of the instruments used, and the applications and inferences derived from measurements. Each chapter has been fully revised to account for the latest developments, including the use of CCDs. Highly illustrated, this book provides an overview and historical background of the subject before reviewing the main themes within astronomical photometry. The central chapters focus on the practical design of the instruments and methodology used. The book concludes by discussing specialized topics in stellar astronomy, concentrating on the information that can be derived from the analysis of the light curves of variable stars and close binary systems. This new edition includes numerous bibliographic notes and a glossary of terms. It is ideal for graduate students, academic researchers and advanced amateurs interested in practical and observational astronomy. Edwin Budding is a research fellow at the Carter Observatory, New Zealand, and a visiting professor at the Çanakkale University, Turkey. Osman Demircan is Director of the Ulupınar Observatory of Çanakkale University, Turkey. Cambridge Observing Handbooks for Research Astronomers Today’s professional astronomers must be able to adapt to use telescopes and interpret data at all wavelengths. This series is designed to provide them with a collection of concise, self-contained handbooks, which covers the basic principles peculiar to observing in a particular spectral region, or to using a special technique or type of instrument. The books can be used as an introduction to the subject and as a handy reference for use at the telescope, or in the office. -

Evidence for Intrinsic Redshifts in Normal Spiral Galaxies

1 Evidence for Intrinsic Redshifts in Normal Spiral Galaxies David G. Russell Owego Free Academy, Owego, NY 13827 USA [email protected] Abstract The Tully-Fisher Relationship (TFR) is utilized to identify anomalous redshifts in normal spiral galaxies. Three redshift anomalies are identified in this analysis: (1) Several clusters of galaxies are examined in which late type spirals have significant excess redshifts relative to early type spirals in the same clusters, (2) Galaxies of morphology similar to ScI galaxies are found to have a systematic excess redshift relative to the redshifts expected if the Hubble Constant is 72 km s-1 Mpc-1, (3) individual galaxies, pairs, and groups are identified which strongly deviate from the predictions of a smooth Hubble flow. These redshift deviations are significantly larger than can be explained by peculiar motions and TFR errors. It is concluded that the redshift anomalies identified in this analysis are consistent with previous claims for large non-cosmological (intrinsic) redshifts. Keywords: Galaxies: distances and Redshifts 1. Introduction Empirical evidence has accumulated which indicates that some quasars and other high redshift objects may not be at the large cosmological distances expected from the traditional redshift-distance relation (Arp1987,1998a, 1999; Chu et al 1998; Bell 2002; Lopez-Corredoira&Gutierrez 2002, 2004; Gutierrez & Lopez-Corredoira 2004). The emerging picture is that some quasars may be ejected from active Seyfert galaxies as high redshift objects that evolve to lower redshifts as they age. Recently, Lopez-Corredoira & Gutierrez (2002, 2004) demonstrated that a pair of high z HII galaxies are present in a luminous filament apparently connecting the Seyfert galaxy NGC 7603 to the companion galaxy NGC 7603B which is previously known to have a discordant redshift. -

Making a Sky Atlas

Appendix A Making a Sky Atlas Although a number of very advanced sky atlases are now available in print, none is likely to be ideal for any given task. Published atlases will probably have too few or too many guide stars, too few or too many deep-sky objects plotted in them, wrong- size charts, etc. I found that with MegaStar I could design and make, specifically for my survey, a “just right” personalized atlas. My atlas consists of 108 charts, each about twenty square degrees in size, with guide stars down to magnitude 8.9. I used only the northernmost 78 charts, since I observed the sky only down to –35°. On the charts I plotted only the objects I wanted to observe. In addition I made enlargements of small, overcrowded areas (“quad charts”) as well as separate large-scale charts for the Virgo Galaxy Cluster, the latter with guide stars down to magnitude 11.4. I put the charts in plastic sheet protectors in a three-ring binder, taking them out and plac- ing them on my telescope mount’s clipboard as needed. To find an object I would use the 35 mm finder (except in the Virgo Cluster, where I used the 60 mm as the finder) to point the ensemble of telescopes at the indicated spot among the guide stars. If the object was not seen in the 35 mm, as it usually was not, I would then look in the larger telescopes. If the object was not immediately visible even in the primary telescope – a not uncommon occur- rence due to inexact initial pointing – I would then scan around for it. -

Deep Sky Explorer Atlas

Deep Sky Explorer Atlas Reference manual Star charts for the southern skies Compiled by Auke Slotegraaf and distributed under an Attribution-Noncommercial 3.0 Creative Commons license. Version 0.20, January 2009 Deep Sky Explorer Atlas Introduction Deep Sky Explorer Atlas Reference manual The Deep Sky Explorer’s Atlas consists of 30 wide-field star charts, from the south pole to declination +45°, showing all stars down to 8th magnitude and over 1 000 deep sky objects. The design philosophy of the Atlas was to depict the night sky as it is seen, without the clutter of constellation boundary lines, RA/Dec fiducial markings, or other labels. However, constellations are identified by their standard three-letter abbreviations as a minimal aid to orientation. Those wishing to use charts showing an array of invisible lines, numbers and letters will find elsewhere a wide selection of star charts; these include the Herald-Bobroff Astroatlas, the Cambridge Star Atlas, Uranometria 2000.0, and the Millenium Star Atlas. The Deep Sky Explorer Atlas is very much for the explorer. Special mention should be made of the excellent charts by Toshimi Taki and Andrew L. Johnson. Both are free to download and make ideal complements to this Atlas. Andrew Johnson’s wide-field charts include constellation figures and stellar designations and are highly recommended for learning the constellations. They can be downloaded from http://www.cloudynights.com/item.php?item_id=1052 Toshimi Taki has produced the excellent “Taki’s 8.5 Magnitude Star Atlas” which is a serious competitor for the commercial Uranometria atlas. His atlas has 149 charts and is available from http://www.asahi-net.or.jp/~zs3t-tk/atlas_85/atlas_85.htm Suggestions on how to use the Atlas Because the Atlas is distributed in digital format, its pages can be printed on a standard laser printer as needed. -

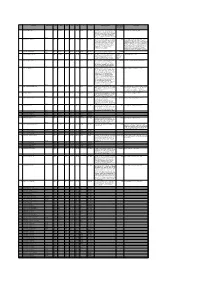

ASSA Top 100 Deep Sky Objects

# Object ID Bennett ID Type Size Con RA Dec D Vis Interesting Facts Distance from Discoverer Earth (light- years) 1 NGC 55, LEDA 1014 Glxy 32’x5.6’ Scl 00 15 – 39 11 06,25 Sep–Feb The String of Pearls. A barred galaxy that is 7200000 James Dunlop on August 4, 1826 edge-on to us. It has a bright elongated center with a small round cloud to the east of it. If you look to the side of it while still concentrating on the object you might be able to see additional bright clouds and dark Ben 1 rifts in this galaxy. 2 NGC 104, 47 Tucanae Glcl 31’ Tuc 00 24 – 72 05 05,06 Sep–Feb The cluster appears roughly the size of the 16700 Abbe Lacaille from South Africa, 1751. At the full moon in the sky under ideal conditions. Cape, Abbé wanted to test Newton's theory of It is the second brightest globular cluster in gravitation and verify the shape of the earth in the the sky (after Omega Centauri), and is southern hemisphere. His results suggested the noted for having a very bright and dense Earth was egg-shaped not oval. In 1838, Thomas core. It is also one of the most massive Maclear who was Astronomer Royal at the Cape, globular clusters in the Milky Way, repeated the measurements. He found that de containing millions of stars Lacaille had failed to take into account the gravitational attraction of the nearby mountains. Ben 2 3 NGC 247, LEDA 2758 Glxy 18’ x 5’ Cet 00 47 – 20 46 06,25 Sep–Feb Very dusty galaxy therefore not bright, 11000000 ? Ben 3 magnitude 9.2, challenging to find. -

Multiple Galaxies - F

Multiple Galaxies - F. Zwicky file:///e|/moe/HTML/March02/Zwicky/Zwicky.htm MULTIPLE GALAXIES F. Zwicky Table of Contents DEFINITIONS REMARKS ON THE HISTORY OF THE SUBJECT A. Small Groups of Galaxies Clusters of Galaxies Recent Advances Instrumentation WIDELY SEPARATED INTERCONNECTED GALAXIES The Triple System IC 3481, Anon, IC 3483 KEENAN's System Another Remarkable Filamentary Structure WILD'S Triple Galaxy The Basic Types of Structures Some Conclusions LONG EXTENSIONS AND SPURS OF SINGLE AND OF MULTIPLE GALAXIES NGC 4038-4039 NGC 750-751 A System in Leo NGC 4651 and Dwarf Companion NGC 3628 and Faint Extensions Spiral Galaxy with One Long Arm SOME SPECIAL PROBLEMS The Milky Way System and the Magellanic Clouds The Andromeda Nebula and its Companions New Clues on the Sense of Rotation of Spiral Galaxies Multiple Galaxies in Clusters and in the General Field OUTLOOK AND PROGRAMS REFERENCES 1. DEFINITIONS The meaning of the term multiple galaxies obviously can be clear only if we know what an individual galaxy is. Unfortunately it is not at the present time possible to give an exact definition of a galaxy as a physical stellar system which is in practice operationally useful. Theoretically one might postulate that any agglomeration of stars, gases and solid particles constitutes a galaxy if its various material components cannot escape directly from this agglomeration. A stellar system or galaxy is therefore a cohesive unit of stars, dust and gases within which only a fraction of its components possess velocities high enough to allow them to escape and to make their way to the vast intergalactic spaces. -

Charles Messier (1730-1817) Was an Observational Astronomer Working

Charles Messier (1730-1817) was an observational Catalogue (NGC) which was being compiled at the same astronomer working from Paris in the eighteenth century. time as Messier's observations but using much larger tele He discovered between 15 and 21 comets and observed scopes, probably explains its modern popularity. It is a many more. During his observations he encountered neb challenging but achievable task for most amateur astron ulous objects that were not comets. Some of these objects omers to observe all the Messier objects. At «star parties" were his own discoveries, while others had been known and within astronomy clubs, going for the maximum before. In 1774 he published a list of 45 of these nebulous number of Messier objects observed is a popular competi objects. His purpose in publishing the list was so that tion. Indeed at some times of the year it is just about poss other comet-hunters should not confuse the nebulae with ible to observe most of them in a single night. comets. Over the following decades he published supple Messier observed from Paris and therefore the most ments which increased the number of objects in his cata southerly object in his list is M7 in Scorpius with a decli logue to 103 though objects M101 and M102 were in fact nation of -35°. He also missed several objects from his list the same. Later other astronomers added a replacement such as h and X Per and the Hyades which most observers for M102 and objects 104 to 110. It is now thought proba would feel should have been included. -

NASA Reference Publication 1203

NASA Reference Publication 1203 June 1988 International Ultraviolet Explorer Spectral Atlas of Planetary Nebulae, Central Stars, and Related Objects Walter A. Feibelman Nancy A. Oliversen Joy Nichols-Bohlin . :;\'I Matthew P. Garhart . i. ., -' .: .. d :. I I.' , y\r~.zLE'( i7;SZkRCt.I CEI'dTEZ L!BSATZ'I, NASA ~3,rL~TC~J.'J!FS!!!!fi NASA Reference Publication 1203 International Ultraviolet Explorer Spectral Atlas of Planetary Nebulae, Central Stars, and Related Objects Walter A. Feibelman Goddard Space Flight Center Greenbelt, Maryland Nancy A. Oliversen Joy Nichols-Bohlin Matthew P. Garhart Computer Sciences Corporation Beltsville, Maryland Series Organizer: Jaylee M. Mead Goddard Space Flight Center National Aeronautics and Space Administration Scientific and Technical Information Division IUE SPECTRAL ATLAS OF PLANETARY NEBULAE, CENTRAL STARS, AND RELATED OBJECTS Walter A. Feibelman Laboratory for Astronomy and Solar Physics, NASA-GSFC and Nancy A. Oliversen, Joy Nichols-Bohlin, and Matthew P. Garhart Astronomy Programs, Computer Sciences Corporation INTRODUCTION Co1.(3) Right Ascension (RA) and Declination (DEC) (1950 epoch), taken from the IUE Merged Nine years of observations with the International Ultraviolet Explorer (IUE) satellite have Log of Observations for the illustrated spectra. The coordinates in the merged log are provided resulted in a data bank of approximately 180 objects in the category of planetary nebulae, their by the guest observer on the observing "script." Slight variations for the coordinates may be found central stars, and related objects. Most of these objects have been observed in the low dispersion in the Merged Log of Observations of duplicate observations due to individual guest observers using mode with both the short wavelength (SWP) and long wavelength (LWR or LWP) cameras.