Arxiv:1905.10771V3 [Astro-Ph.HE] 28 May 2020 .S Ja .Ojha R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Messier Objects

Messier Objects From the Stocker Astroscience Center at Florida International University Miami Florida The Messier Project Main contributors: • Daniel Puentes • Steven Revesz • Bobby Martinez Charles Messier • Gabriel Salazar • Riya Gandhi • Dr. James Webb – Director, Stocker Astroscience center • All images reduced and combined using MIRA image processing software. (Mirametrics) What are Messier Objects? • Messier objects are a list of astronomical sources compiled by Charles Messier, an 18th and early 19th century astronomer. He created a list of distracting objects to avoid while comet hunting. This list now contains over 110 objects, many of which are the most famous astronomical bodies known. The list contains planetary nebula, star clusters, and other galaxies. - Bobby Martinez The Telescope The telescope used to take these images is an Astronomical Consultants and Equipment (ACE) 24- inch (0.61-meter) Ritchey-Chretien reflecting telescope. It has a focal ratio of F6.2 and is supported on a structure independent of the building that houses it. It is equipped with a Finger Lakes 1kx1k CCD camera cooled to -30o C at the Cassegrain focus. It is equipped with dual filter wheels, the first containing UBVRI scientific filters and the second RGBL color filters. Messier 1 Found 6,500 light years away in the constellation of Taurus, the Crab Nebula (known as M1) is a supernova remnant. The original supernova that formed the crab nebula was observed by Chinese, Japanese and Arab astronomers in 1054 AD as an incredibly bright “Guest star” which was visible for over twenty-two months. The supernova that produced the Crab Nebula is thought to have been an evolved star roughly ten times more massive than the Sun. -

X-Ray and Gamma-Ray Variability of NGC 1275

galaxies Article X-ray and Gamma-ray Variability of NGC 1275 Varsha Chitnis 1,*,† , Amit Shukla 2,*,† , K. P. Singh 3 , Jayashree Roy 4 , Sudip Bhattacharyya 5, Sunil Chandra 6 and Gordon Stewart 7 1 Department of High Energy Physics, Tata Institute of Fundamental Research, Homi Bhabha Road, Mumbai 400005, India 2 Discipline of Astronomy, Astrophysics and Space Engineering, Indian Institute of Technology Indore, Khandwa Road, Simrol, Indore 453552, India 3 Indian Institute of Science Education and Research Mohali, Knowledge City, Sector 81, SAS Nagar, Manauli 140306, India; [email protected] 4 Inter-University Centre for Astronomy and Astrophysics, Ganeshkhind, Pune 411 007, India; [email protected] 5 Department of Astronomy and Astrophysics, Tata Institute of Fundamental Research, Homi Bhabha Road, Mumbai 400005, India; [email protected] 6 Centre for Space Research, North-West University, Potchefstroom 2520, South Africa; [email protected] 7 Department of Physics and Astronomy, The University of Leicester, University Road, Leicester LE1 7RH, UK; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] (V.C.); [email protected] (A.S.) † These authors contributed equally to this work. Received: 30 June 2020; Accepted: 24 August 2020; Published: 28 August 2020 Abstract: Gamma-ray emission from the bright radio source 3C 84, associated with the Perseus cluster, is ascribed to the radio galaxy NGC 1275 residing at the centre of the cluster. Study of the correlated X-ray/gamma-ray emission from this active galaxy, and investigation of the possible disk-jet connection, are hampered because the X-ray emission, particularly in the soft X-ray band (2–10 keV), is overwhelmed by the cluster emission. -

![Arxiv:1705.04776V1 [Astro-Ph.HE] 13 May 2017 Aaua M](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2598/arxiv-1705-04776v1-astro-ph-he-13-may-2017-aaua-m-302598.webp)

Arxiv:1705.04776V1 [Astro-Ph.HE] 13 May 2017 Aaua M

White Paper on East Asian Vision for mm/submm VLBI: Toward Black Hole Astrophysics down to Angular Resolution of 1 RS Editors Asada, K.1, Kino, M.2,3, Honma, M.3, Hirota, T.3, Lu, R.-S.4,5, Inoue, M.1, Sohn, B.-W.2,6, Shen, Z.-Q.4, and Ho, P. T. P.1,7 Authors Akiyama, K.3,8, Algaba, J-C.2, An, T.4, Bower, G.1, Byun, D-Y.2, Dodson, R.9, Doi, A.10, Edwards, P.G.11, Fujisawa, K.12, Gu, M-F.4, Hada, K.3, Hagiwara, Y.13, Jaroenjittichai, P.15, Jung, T.2,6, Kawashima, T.3, Koyama, S.1,5, Lee, S-S.2, Matsushita, S.1, Nagai, H.3, Nakamura, M.1, Niinuma, K.12, Phillips, C.11, Park, J-H.15, Pu, H-Y.1, Ro, H-W.2,6, Stevens, J.11, Trippe, S.15, Wajima, K.2, Zhao, G-Y.2 1 Institute of Astronomy and Astrophysics, Academia Sinica, P.O. Box 23-141, Taipei 10617, Taiwan 2 Korea Astronomy and Space Science Institute, Daedukudae-ro 776, Yuseong-gu, Daejeon 34055, Republic of Korea 3 National Astronomical Observatory of Japan, 2-21-1 Osawa, Mitaka, Tokyo, 181-8588, Japan 4 Shanghai Astronomical Observatory, Chinese Academy of Sciences, 80 Nandan Road, Shanghai 200030, China 5 Max-Planck-Institut f¨ur Radioastronomie, Auf dem H¨ugel 69, D-53121 Bonn, Germany 6 University of Science and Technology, 217 Gajeong-ro, Yuseong-gu, Daejeon 34113, Republic of Korea 7 East Asian Observatory, 660 N. -

A Basic Requirement for Studying the Heavens Is Determining Where In

Abasic requirement for studying the heavens is determining where in the sky things are. To specify sky positions, astronomers have developed several coordinate systems. Each uses a coordinate grid projected on to the celestial sphere, in analogy to the geographic coordinate system used on the surface of the Earth. The coordinate systems differ only in their choice of the fundamental plane, which divides the sky into two equal hemispheres along a great circle (the fundamental plane of the geographic system is the Earth's equator) . Each coordinate system is named for its choice of fundamental plane. The equatorial coordinate system is probably the most widely used celestial coordinate system. It is also the one most closely related to the geographic coordinate system, because they use the same fun damental plane and the same poles. The projection of the Earth's equator onto the celestial sphere is called the celestial equator. Similarly, projecting the geographic poles on to the celest ial sphere defines the north and south celestial poles. However, there is an important difference between the equatorial and geographic coordinate systems: the geographic system is fixed to the Earth; it rotates as the Earth does . The equatorial system is fixed to the stars, so it appears to rotate across the sky with the stars, but of course it's really the Earth rotating under the fixed sky. The latitudinal (latitude-like) angle of the equatorial system is called declination (Dec for short) . It measures the angle of an object above or below the celestial equator. The longitud inal angle is called the right ascension (RA for short). -

The Third Catalog of Active Galactic Nuclei Detected by the Fermi Large Area Telescope M

The Astrophysical Journal, 810:14 (34pp), 2015 September 1 doi:10.1088/0004-637X/810/1/14 © 2015. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. THE THIRD CATALOG OF ACTIVE GALACTIC NUCLEI DETECTED BY THE FERMI LARGE AREA TELESCOPE M. Ackermann1, M. Ajello2, W. B. Atwood3, L. Baldini4, J. Ballet5, G. Barbiellini6,7, D. Bastieri8,9, J. Becerra Gonzalez10,11, R. Bellazzini12, E. Bissaldi13, R. D. Blandford14, E. D. Bloom14, R. Bonino15,16, E. Bottacini14, T. J. Brandt10, J. Bregeon17, R. J. Britto18, P. Bruel19, R. Buehler1, S. Buson8,9, G. A. Caliandro14,20, R. A. Cameron14, M. Caragiulo13, P. A. Caraveo21, B. Carpenter10,22, J. M. Casandjian5, E. Cavazzuti23, C. Cecchi24,25, E. Charles14, A. Chekhtman26, C. C. Cheung27, J. Chiang14, G. Chiaro9, S. Ciprini23,24,28, R. Claus14, J. Cohen-Tanugi17, L. R. Cominsky29, J. Conrad30,31,32,70, S. Cutini23,24,28,R.D’Abrusco33,F.D’Ammando34,35, A. de Angelis36, R. Desiante6,37, S. W. Digel14, L. Di Venere38, P. S. Drell14, C. Favuzzi13,38, S. J. Fegan19, E. C. Ferrara10, J. Finke27, W. B. Focke14, A. Franckowiak14, L. Fuhrmann39, Y. Fukazawa40, A. K. Furniss14, P. Fusco13,38, F. Gargano13, D. Gasparrini23,24,28, N. Giglietto13,38, P. Giommi23, F. Giordano13,38, M. Giroletti34, T. Glanzman14, G. Godfrey14, I. A. Grenier5, J. E. Grove27, S. Guiriec10,2,71, J. W. Hewitt41,42, A. B. Hill14,43,68, D. Horan19, R. Itoh40, G. Jóhannesson44, A. S. Johnson14, W. N. Johnson27, J. Kataoka45,T.Kawano40, F. Krauss46, M. Kuss12, G. La Mura9,47, S. Larsson30,31,48, L. -

Herschel Observations of Extended Atomic Gas in the Core of the Perseus Cluster R

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Physics and Astronomy Faculty Publications Physics and Astronomy 2012 Herschel Observations of Extended Atomic Gas in the Core of the Perseus Cluster R. Mittal Rochester Institute of Technology J. B. R. Oonk Netherlands Institute for Radio Astronomy, Netherlands Gary J. Ferland University of Kentucky, [email protected] A. C. Edge Durham University, UK C. P. O'Dea Rochester Institute of Technology See next page for additional authors Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits oy u. Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/physastron_facpub Part of the Astrophysics and Astronomy Commons, and the Physics Commons Repository Citation Mittal, R.; Oonk, J. B. R.; Ferland, Gary J.; Edge, A. C.; O'Dea, C. P.; Baum, S. A.; Whelan, J. T.; Johnstone, R. M.; Combes, F.; Salomé, P.; Fabian, A. C.; Tremblay, G. R.; Donahue, M.; and H., Russell H., "Herschel Observations of Extended Atomic Gas in the Core of the Perseus Cluster" (2012). Physics and Astronomy Faculty Publications. 29. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/physastron_facpub/29 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Physics and Astronomy at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Physics and Astronomy Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Authors R. Mittal, J. B. R. Oonk, Gary J. Ferland, A. C. Edge, C. P. O'Dea, S. A. Baum, J. T. Whelan, R. M. Johnstone, F. Combes, P. Salomé, A. C. -

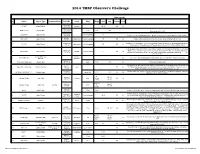

2014 Observers Challenge List

2014 TMSP Observer's Challenge Atlas page #s # Object Object Type Common Name RA, DEC Const Mag Mag.2 Size Sep. U2000 PSA 18h31m25s 1 IC 1287 Bright Nebula Scutum 20'.0 295 67 -10°47'45" 18h31m25s SAO 161569 Double Star 5.77 9.31 12.3” -10°47'45" Near center of IC 1287 18h33m28s NGC 6649 Open Cluster 8.9m Integrated 5' -10°24'10" Can be seen in 3/4d FOV with above. Brightest star is 13.2m. Approx 50 stars visible in Binos 18h28m 2 NGC 6633 Open Cluster Ophiuchus 4.6m integrated 27' 205 65 Visible in Binos and is about the size of a full Moon, brightest star is 7.6m +06°34' 17h46m18s 2x diameter of a full Moon. Try to view this cluster with your naked eye, binos, and a small scope. 3 IC 4665 Open Cluster Ophiuchus 4.2m Integrated 60' 203 65 +05º 43' Also check out “Tweedle-dee and Tweedle-dum to the east (IC 4756 and NGC 6633) A loose open cluster with a faint concentration of stars in a rich field, contains about 15-20 stars. 19h53m27s Brightest star is 9.8m, 5 stars 9-11m, remainder about 12-13m. This is a challenge obJect to 4 Harvard 20 Open Cluster Sagitta 7.7m integrated 6' 162 64 +18°19'12" improve your observation skills. Can you locate the miniature coathanger close by at 19h 37m 27s +19d? Constellation star Corona 5 Corona Borealis 55 Trace the 7 stars making up this constellation, observe and list the colors of each star asterism Borealis 15H 32' 55” Theta Corona Borealis Double Star 4.2m 6.6m .97” 55 Theta requires about 200x +31° 21' 32” The direction our Sun travels in our galaxy. -

Counting Gamma Rays in the Directions of Galaxy Clusters

A&A 567, A93 (2014) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201322454 & c ESO 2014 Astrophysics Counting gamma rays in the directions of galaxy clusters D. A. Prokhorov1 and E. M. Churazov1,2 1 Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics, Karl-Schwarzschild-Strasse 1, 85741 Garching, Germany e-mail: [email protected] 2 Space Research Institute (IKI), Profsouznaya 84/32, 117997 Moscow, Russia Received 6 August 2013 / Accepted 19 May 2014 ABSTRACT Emission from active galactic nuclei (AGNs) and from neutral pion decay are the two most natural mechanisms that could establish a galaxy cluster as a source of gamma rays in the GeV regime. We revisit this problem by using 52.5 months of Fermi-LAT data above 10 GeV and stacking 55 clusters from the HIFLUCGS sample of the X-ray brightest clusters. The choice of >10 GeV photons is optimal from the point of view of angular resolution, while the sample selection optimizes the chances of detecting signatures of neutral pion decay, arising from hadronic interactions of relativistic protons with an intracluster medium, which scale with the X-ray flux. In the stacked data we detected a signal for the central 0.25 deg circle at the level of 4.3σ. Evidence for a spatial extent of the signal is marginal. A subsample of cool-core clusters has a higher count rate of 1.9 ± 0.3 per cluster compared to the subsample of non-cool core clusters at 1.3 ± 0.2. Several independent arguments suggest that the contribution of AGNs to the observed signal is substantial, if not dominant. -

Globular Clusters and Galactic Nuclei

Scuola di Dottorato “Vito Volterra” Dottorato di Ricerca in Astronomia– XXIV ciclo Globular Clusters and Galactic Nuclei Thesis submitted to obtain the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (“Dottore di Ricerca”) in Astronomy by Alessandra Mastrobuono Battisti Program Coordinator Thesis Advisor Prof. Roberto Capuzzo Dolcetta Prof. Roberto Capuzzo Dolcetta Anno Accademico 2010-2011 ii Abstract Dynamical evolution plays a key role in shaping the current properties of star clus- ters and star cluster systems. We present the study of stellar dynamics both from a theoretical and numerical point of view. In particular we investigate this topic on different astrophysical scales, from the study of the orbital evolution and the mutual interaction of GCs in the Galactic central region to the evolution of GCs in the larger scale galactic potential. Globular Clusters (GCs), very old and massive star clusters, are ideal objects to explore many aspects of stellar dynamics and to investigate the dynamical and evolutionary mechanisms of their host galaxy. Almost every surveyed galaxy of sufficiently large mass has an associated group of GCs, i.e. a Globular Cluster System (GCS). The first part of this Thesis is devoted to the study of the evolution of GCSs in elliptical galaxies. Basing on the hypothesis that the GCS and stellar halo in a galaxy were born at the same time and, so, with the same density distribution, a logical consequence is that the presently observed difference may be due to evolution of the GCS. Actually, in this scenario, GCSs evolve due to various mechanisms, among which dynamical friction and tidal interaction with the galactic field are the most important. -

Long-Term Study of a Gamma-Ray Emitting Radio Galaxy NGC 1275

Long-term study of a gamma-ray emitting radio galaxy NGC 1275 Yasushi Fukazawa (Hiroshima University) 8th Fermi Symposium @ Baltimore 1 Multi-wavelength variability of a gamma- ray emitting radio galaxy NGC 1275 Yasushi Fukazawa (Hiroshima University) 8th Fermi Symposium @ Baltimore 2 Outline Introduction GeV/gamma-ray and TeV studies Radio and gamma-ray connection X-ray and gamma-ray connection Optical/UV and gamma-ray connection Summary and future prospective Papers on NGC 1275 X-ray/gamma-ray studies in 2015-2018 Nustar view of the central region of the Perseus cluster; Rani+18 Gamma-ray flaring activity of NGC1275 in 2016-2017 measured by MAGIC; Magic+18 The Origins of the Gamma-Ray Flux Variations of NGC 1275 Based on Eight Years of Fermi-LAT Observations; Tanada+18 X-ray and GeV gamma-ray variability of the radio galaxy NGC 1275; Fukazawa+18 Hitomi observation of radio galaxy NGC 1275: The first X-ray microcalorimeter spectroscopy of Fe-Kα line emission from an active galactic nucleus; Hitomi+18 Rapid Gamma-Ray Variability of NGC 1275; Baghmanyan+17 Deep observation of the NGC 1275 region with MAGIC: search of diffuse γ-ray emission from cosmic rays in the Perseus cluster; Fabian+15 More papers on radio/optical observations NGC 1275 Interesting and important object for time-domain and multi-wavelength astrophysics Radio galaxies Parent population of Blazars Unlike blazars, their jet is not aligned to the line of sight, beaming is weaker. EGRET: Cen A detection and a hint of a few radio galaxies 3EG catalog: Hartman et al. -

The Messier Catalog

The Messier Catalog Messier 1 Messier 2 Messier 3 Messier 4 Messier 5 Crab Nebula globular cluster globular cluster globular cluster globular cluster Messier 6 Messier 7 Messier 8 Messier 9 Messier 10 open cluster open cluster Lagoon Nebula globular cluster globular cluster Butterfly Cluster Ptolemy's Cluster Messier 11 Messier 12 Messier 13 Messier 14 Messier 15 Wild Duck Cluster globular cluster Hercules glob luster globular cluster globular cluster Messier 16 Messier 17 Messier 18 Messier 19 Messier 20 Eagle Nebula The Omega, Swan, open cluster globular cluster Trifid Nebula or Horseshoe Nebula Messier 21 Messier 22 Messier 23 Messier 24 Messier 25 open cluster globular cluster open cluster Milky Way Patch open cluster Messier 26 Messier 27 Messier 28 Messier 29 Messier 30 open cluster Dumbbell Nebula globular cluster open cluster globular cluster Messier 31 Messier 32 Messier 33 Messier 34 Messier 35 Andromeda dwarf Andromeda Galaxy Triangulum Galaxy open cluster open cluster elliptical galaxy Messier 36 Messier 37 Messier 38 Messier 39 Messier 40 open cluster open cluster open cluster open cluster double star Winecke 4 Messier 41 Messier 42/43 Messier 44 Messier 45 Messier 46 open cluster Orion Nebula Praesepe Pleiades open cluster Beehive Cluster Suburu Messier 47 Messier 48 Messier 49 Messier 50 Messier 51 open cluster open cluster elliptical galaxy open cluster Whirlpool Galaxy Messier 52 Messier 53 Messier 54 Messier 55 Messier 56 open cluster globular cluster globular cluster globular cluster globular cluster Messier 57 Messier -

Introduction to Astronomical Photometry, Second Edition

This page intentionally left blank Introduction to Astronomical Photometry, Second Edition Completely updated, this Second Edition gives a broad review of astronomical photometry to provide an understanding of astrophysics from a data-based perspective. It explains the underlying principles of the instruments used, and the applications and inferences derived from measurements. Each chapter has been fully revised to account for the latest developments, including the use of CCDs. Highly illustrated, this book provides an overview and historical background of the subject before reviewing the main themes within astronomical photometry. The central chapters focus on the practical design of the instruments and methodology used. The book concludes by discussing specialized topics in stellar astronomy, concentrating on the information that can be derived from the analysis of the light curves of variable stars and close binary systems. This new edition includes numerous bibliographic notes and a glossary of terms. It is ideal for graduate students, academic researchers and advanced amateurs interested in practical and observational astronomy. Edwin Budding is a research fellow at the Carter Observatory, New Zealand, and a visiting professor at the Çanakkale University, Turkey. Osman Demircan is Director of the Ulupınar Observatory of Çanakkale University, Turkey. Cambridge Observing Handbooks for Research Astronomers Today’s professional astronomers must be able to adapt to use telescopes and interpret data at all wavelengths. This series is designed to provide them with a collection of concise, self-contained handbooks, which covers the basic principles peculiar to observing in a particular spectral region, or to using a special technique or type of instrument. The books can be used as an introduction to the subject and as a handy reference for use at the telescope, or in the office.