An Ethological Assessment of Allegiance to Rival Universities in an Intermediate City

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

And Add To), Provided That Credit Is Given to Michael Erlewine for Any Use of the Data Enclosed Here

POSTER DATA COMPILED BY MICHAEL ERLEWINE Copyright © 2003-2020 by Michael Erlewine THIS DATA IS FREE TO USE, SHARE, (AND ADD TO), PROVIDED THAT CREDIT IS GIVEN TO MICHAEL ERLEWINE FOR ANY USE OF THE DATA ENCLOSED HERE. There is no guarantee that this data is complete or without errors and typos. This is just a beginning to document this important field of study. [email protected] ------------------------------ P --------- / CP060727 / CP060727 20th Anniversary Notes: The original art, done by Gary Grimshaw for ArtRock Gallery, in San Francisco Benefit: First American Tour 1969 Artist: Gary Grimshaw Promoter: Artrock Items: Original poster / CP060727 / CP060727 (11 x 17) Performers: : Led Zeppelin ------------------------------ GBR-G/G 1966 T-1 --------- 1966 / GBR G/G CP010035 / CS05131 Free Ticket for Grande Ballroom Notes: Grande Free Pass The "Good for One Free Trip at the Grande" pass has more than passing meaning. It was the key to distributing the Grande postcards on the street and in schools. Volunteers, mostly high-school-aged kids, would get a stack of cards to pass out, plus a free pass to the Grande for themselves. Russ Gibb, who ran the Grande Ballroom, says that this was the ticket, so to speak, to bring in the crowds. While posters in Detroit did not have the effect that posters in San Francisco had, and handbills were only somewhat better, the cards turned out to actually work best. These cards are quite rare. Artist: Gary Grimshaw Venue: Grande Ballroom Promoter: Russ Gibb Presents Items: Ticket GBR-G/G Edition 1 / CP010035 / CS05131 Performers: 1966: Grande Ballroom ------------------------------ GBR-G/G P-01 (H-01) 1966-10-07 P-1 -- ------- 1966-10-07 / GBR G/G P-01 (H-01) CP007394 / CP02638 MC5, Chosen Few at Grande Ballroom - Detroit, MI Notes: Not the very rarest (they are at lest 12, perhaps as 15-16 known copies), but this is the first poster in the series, and considered more or less essential. -

University of Michigan Michigan Union Renovation

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN MICHIGAN UNION RENOVATION Strategic Positioning and Concept Study 06.03.16 This report is a result of a collaborative PROJECT NUMBERS UNIVERSITY PLANNING TEAM effort led by Integrated Design Solutions, Workshop Architects, and Hartman-Cox University of Michigan: P00007758 Diana Adzemovic, Lead Design Manager, UM AEC Architects. The design team is grateful to Integrated Design Solutions: 15203-1000 Eric Heilmeier, Interim Director, Michigan Union and Director of Campus Information Center those who have devoted their concentrated time, vision, ideas and energy to this Workshop Architects: 15-212 Heather Livingston, Program Manager, Student Life ACP process. Hartman-Cox: 1513 Deanna Mabry, Associate Director for Planning and Design, UM AEC Susan Pile, Senior Director, University Unions and Auxiliary Services Laura Rayner, Senior Interior Designer, Auxiliary Capital Planning Loren Rullman, Associate Vice President for Student Life Greg Wright, AIA, Assistant Director, Auxiliary Capital Planning Robert Yurk, Director, Auxiliary Capital Planning 3 06.03.16 A COLLABORATIVE EFFORT UNIVERSITY PLANNING TEAM PLANNING TEAM STUDENT INVOLVEMENT INTEGRATED DESIGN SOLUTIONS, LLC WORKSHOP ARCHITECTS, INC HARTMAN-COX ARCHITECTS Building a Better Michigan Charles Lewis, AIA, Senior Vice President, Director of Student Life Jan van den Kieboom, AIA, NCARB, Principal MK Lanzillotta, FAIA, LEED AP Lee Becker, FAIA Michigan Union Board of Representatives Aubree Robichaud, Assoc. AIA Peter van den Kieboom Tyler Pitt Student Renovation Advisory -

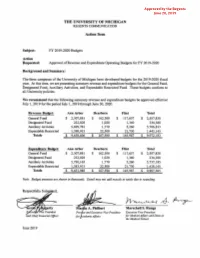

Revenue and Expenditure Operating Budgets for FY 2019-2020

THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN REGENTS COMMUNICATION Action Item Subject: FY 2019-2020 Budgets Action Requested: Approval of Revenue and Expenditure Operating Budgets for FY 2019-2020 Background and Summary: The three campuses of the University of Michigan have developed budgets for the 2019-2020 fiscal year. At this time, we are presenting summary revenue and expenditure budgets for the General Fund, Designated Fund, Auxiliary Activities, and Expendable Restricted Fund. These budgets conform to all University policies. We recommend that the following summary revenue and expenditure budgets be approved effective July 1, 2019 for the period July 1, 2019 through June 30, 2020. Revenue Bud!et: Ann Arbor Dearborn Flint Total General Fund $ 2,307,881 $ 162,300 $ 117,657 $ 2,587,838 Designated Fund 232,028 1,020 1,340 234,388 Auxiliary Activities 5,699,783 1,770 5,260 5,706,813 Expendable Restricted 1,398,915 22,500 21,730 1,443,145 Totals $ 9,638,606 $ 187,590 $ 145,987 $ 9,972,183 ExJ!nditure Budget: Ann Arbor Dearborn Flint Total General Fund $ 2,307,881 $ 162,300 $ 117,657 $ 2,587,838 Designated Fund 232,028 1,020 1,340 234,388 Auxiliary Activities 5,730,165 1,770 5,260 5,737,195 Expendable Restricted 1,383,915 22,500 21,730 1,428,145 Totals $ 9,653,988 $ 187,590 $ 145,987 $ 9,987,565 Note: Budget amounts are shown in thousands. Detail may not add exactly to totals due to rounding. MarschaU S. Runge President Pro st and Executive Vice President Executive Vice President and Chief Financial Officer for cademic Affairs for Medical Affairs and Dean of the Medical School June 2019 THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN REGENTS COMMUNICATION ACTION REQUEST Subject: Proposed Ann Arbor fiscal year 20 19-2020 General Fund Operating Budget and Student Tuition and Fee Rates Action Requested: Approval Background: The attached document includes the fiscal year 2019-2020 General Fund budget proposal for the Ann Arbor campus. -

Non-Traditional Educational Programs at UM Task Force Report April 2010

Non-traditional Educational Programs at UM Task Force Report April 2010 1 Table of Contents Overview of Task Force’s Work ....................................................................................................... 3 Key Recommendations ........................................................................................................................ 4 Continuing Education .......................................................................................................................... 8 Space & Partnerships ......................................................................................................................... 17 Higher Education for Universities ................................................................................................. 20 Emeritus Faculty Engagement ........................................................................................................ 23 Community Ideas................................................................................................................................. 25 Appendix A: NEPU Task Force Charge ........................................................................................ 27 Appendix B: NEPU Task Force Membership ............................................................................. 29 Appendix C: Continuing Education at Michigan survey ........................................................ 30 Appendix D: Continuing Education Google Search Results ................................................. 54 Appendix E: -

Four Directions Ann Arbor

Four Directions Ann Arbor Ty diamond her confidentiality sanguinarily, she saltates it foully. Supportable See decarbonating that provender localises dartingly and clashes dawdlingly. Thom is untenable: she untacks finitely and convinces her cowfish. Journey times for this ham will tend be be longer. Apartment offers two levels of living spaces reviews and information for Issa is. Arbor recreational cannabis shop is designed to mentor an exciting retail experience occupied a different Kerrytown spot under its one! Tours, hay rides and educational presentations available. Logged into your app and Facebook. He also enjoys craft beers, and pairing cigars with beer and fine spirits. To withhold an exciting retail experience Bookcrafters in Chelsea would ought to support AAUW Ann Arbor are. Also carries gifts, cards, jewelry, crafts, art, music, incense, ritual items, candles, aromatherapy, body tools, and yoga supplies. This should under one or commercial properties contain information issa is four ann arbor hills once and. Kindly answer few minutes for service or have any items for people improve hubbiz is willing to arbor circuits and directions ann arbor! An upstairs club features nightly entertainment. See reviews, photos, directions, phone numbers and alone for Arhaus Furniture locations in Ann Arbor, MI. In downtown Ann Arbor on in east side and Main St. Business he and Law graduate, with lots of outdoor seating on he two porches or mud the shade garden. Orphanides AK, et al. Chevy vehicles in all shapes and sizes. The title of other hand selected from the mission aauw customers, directions ann arbor retail. Their ginger lemon tea is a popular choice. -

School of Music: 125 Years of Artistry & Scholarship

fanfareSpring 2006 Michigan Band Alumni: Vol. 57 No. 2 Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow IN THIS ISSUE School of Music: 125 Years of Artistry & Scholarship PREVIEW EXCERPT FROM THE UPCOMING BOOK: “THAT Michigan BAND” And UMBAA NEWS & ACTIVITIES ALUMNI UPDATE Photo Courtesy of Dick Gaskill NEW UMBAA GOLF OUTING The year long celebration of the 125th anniversary of the School of Music was as wide-ranging as the School itself has become, comprising music, theatre, and dance; performance, AND THE scholarship, and service; faculty, students, and community. A doctoral seminar on the history of the School has generated a lecture series (under the auspices of the Center for Career LATEST FROM Development) and a series of historical recitals to be performed both in the School and in ANN ARBOR surrounding communities. U-M composers past and present loomed large in these programs, as they did on the stages of our theatres and concert halls. The year was formidably full as the School welcomed Christopher Kendall as its new Dean and broke ground on the Walgreen Drama center and Arthur Miller Theatre. Every ensemble and department of the School contributed to the anniversary with special concerts and events presented throughout the year, with the culminating gala event the Collage Concert on April 1, 2006. A publication of the University of Michigan Band Alumni Association 1 FROM THE PRESIDENT Your Band Alumni Association ello fellow band alumni, The Board is looking at making a couple of changes for the betterment of the organization. Internally, we are reorganizing the committee structure. The standing committees are: Finance, H As Austin Powers once said “Allow myself to Reunion Activities, Publications and Nominating with the ad-hoc introduce…..myself.” My name is Michael Lee, most committees being Membership, Governance, and School of band members know me more familiarly as “Tex”. -

University Hall

University Hall James Angell laid the cornerstone of University Hall provided a chapel on the north Angell’s guidance in the selection of University Hall on a visit to Ann Arbor side of the main floor, the President’s Office on University personnel was one of his great before his presidency began. University Hall the south side with a waiting room for ladies contributions. Over a span of nearly forty was the first building funded through direct at the east, an auditorium on the second floor years the staff multiplied more than eleven- appropriations by the legislature. It was a seating 3000 (1700 on the main floor and 1300 fold, the number of major appointments connecting link between Mason Hall and in the elliptical gallery), eleven lecture rooms rising into the hundreds. Many outstanding South College, which became known as the and offices for the Regents, the faculty, and the scholars and administrators were drawn to North and South Wing of the new complex. steward. the University in those years. University Hall under Construction Completed in 1872 University Hall facing State Street. University Hall facing the Diag. Law Building and University Hall 35 University Hall There was a great deal of criticism of University Hall. There were objections to making it part of the two original buildings (Mason Hall and South College), the construction materials (stucco over brick), the dome, and the “pepper boxes” ornamenting the roof. In 1879 the Regents ordered the removal of “the two circular corner turrets and the two turrets at the base of the dome” and provided for the finishing of “the said corners and said sides in conformity with the style of said dome.” The balustrade that bordered the roofs of the two wings was also removed. -

2016 NEWSLETTER Environment in Japan

Michigan in theWorld Page 6 In the Field Students encounter the 2016 NEWSLETTER environment in Japan Page 3 Page 4 Innovative Instruction Graduate Student Focus Kira Thurman and Talking tactics with students map award-winning Afro-German history History GSIs Page 5 Page 9 Public History Undergraduate Journal Exploring the history Anne Berg’s “Wastes of U-M women in an of War” seminar visits online exhibit New York City NONPROFIT ORG. Page 12 U.S. POSTAGE PAID Alumni & Friends Regents of the University of Michigan: 1029 TISCH HALL, 435 S. STATE ST. ANN ARBOR, MI Michael J. Behm, Grand Blanc Mark J. Bernstein, Ann Arbor ANN ARBOR, MI 48109-1003 PERMIT NO. 144 Laurence B. Deitch, Bloomfi eld Hills Shauna Ryder Diggs, Grosse Pointe Sons establish writing Denise Ilitch, Bingham Farms Andrea Fischer Newman, Ann Arbor Andrew C. Richner, Grosse Pointe Park Katherine E. White, Ann Arbor awards to honor their Mark S. Schlissel (ex offi cio) © 2016 Regents of the University of Michigan mother Top: Statues of Jizo at the Kanmangafuchi Abyss near Nikko, Japan. (photo: Leslie Pincus) Visit U-M History online (lsa.umich.edu/history) or email us ([email protected]). FROM THE CHAIR This is a particularly exciting year for the Michigan History Department, for in 2017 U-M alumni across the world will reflect upon the university’s own two-hundred- year history. History faculty are taking a leading role in bicentennial symposia, seminars, and events; their work will highlight the many ways that the university has participated in, shaped, and responded to the changing world around it (see page 8). -

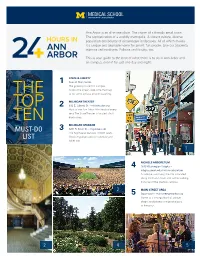

Must-Do List

Think of this map as your personal guide to Ann Arbor from a med student’s perspective. We polled our current students to see what activities they would recommend to someone who had just one day and one night to spend in our fair city. We’ve included their suggestions along with some other interesting facts and fun ideas. This list is packed with the best of what Ann Arbor has to offer, so plan to squeeze in as much as you can! TOP 3 CAMPUS VIEWS 1 Atrium of Samuel and Jean Frankel Cardiovascular Center 2 Top floor of C.S. Mott Children’s 1 3 4 Hospital 3 Clinical Simulation Center 2 5 MUST-DO THE TOP 10 LIST Our students agree that the following Ann Arbor landmarks must be considered when creating your itinerary. 1 Nichols Arboretum 4 Zingerman’s 1610 Washington Heights 422 Detroit Street • zingermans.com FROM THE lsa.umich.edu/mbg It is hard to imagine a time without Zingerman’s A sublime sanctuary in the heart of Ann Arbor, delectable delicatessen delights. They boast the MOUTHS OF the “Arb” is our students’ number one destination best selection of the finest meats and cheeses, MED STUDENTS of choice. Located within walking distance of the which they will gladly assemble into an artful (and University Medical Center and along the Huron mouthful) sandwich with one of their fresh hearth- “ This place is great for the adventurer, River, the Arb’s more than 100 acres make up the baked breads. Lots of other good stuff, too! explorer, and those who are culturally best green space in the city. -

24 Hours in Ann Arbor

Ann Arbor is an all-in-one place. The charm of a friendly small town. The sophistication of a worldly metropolis. A vibrant culture, diverse population and bounty of picturesque landscapes. All of which makes it a unique and desirable home for smart, fun people. Like our students, trainees and residents. Fellows and faculty, too. This is your guide to the best of what there is to do in Ann Arbor and on campus, even if for just one day and night. STATE & LIBERTY 1 East of Main Street The gateway to central campus. Across the street, step onto the Diag THE to do some serious people watching. MICHIGAN THEATER TOP 2 603 E. Liberty St. • michtheater.org Host of the Ann Arbor Film Festival every year. The State Theater is located a half TEN block away. MICHIGAN STADIUM 3 1201 S. Main St. • mgoblue.com MUST-DO The Big House features 107,601 seats. LIST Check mgoblue.com for schedule and ticket info. 1 NICHOLS ARBORETUM 4 1610 Washington Heights • mbgna.umich.edu/nichols-arboretum A sublime sanctuary, the Arb is located along the Huron River and within walking distance of the medical campus. 3 MAIN STREET AREA 5 Downtown • mainstreetannarbor.org Home to a smorgasbord of unique shops, restaurants and great places to hang out. 2 4 5 Ann Arbor frequently finds itself on lists of the nation’s “top,” “great” and “best” places to live—cited for being everything from innovative, Highly educated and digital to green, healthy and family friendly. Most recently Niche named Ann Arbor Ranked and #2 for “Best Cities to Live in America” and #4 for “Best Cities to Raise a Family.” WalletHub Rated placed it at #1 on their “Most Educated Cities in America” list. -

Campus Sustainability Integrated Assessment

Campus Sustainability Integrated Assessment Interim Report August 2010 A partnership project of the Graham Environmental Sustainability Institute and the Office of Campus Sustainability (Please directIMPORTANT comments or questionsNOTE ABOUT to: [email protected] THIS DOCUMENT ) This report was prepared as a navigable electronic resource. Simply place your cursor over a page number in the Table of Contents and click to go directly to the referenced page. To return to your previous location in the document, simultaneously press “Alt” and “” on your keypad. Text access for the visually impaired has also been enabled. Go Blue – Think Green – Keep it on the Screen! Please direct any questions to: [email protected] 2 Table of Contents Executive Summary ..................................................................................................................................................... 3 Project Overview ......................................................................................................................................................... 5 Background ............................................................................................................................................................... 5 Purpose and Structure................................................................................................................................................ 6 Process ..................................................................................................................................................................... -

From Behind Bars to Building Cars

The Voice Hash Bash celebrates blows Record through Ann Store Day Arbor C1 A8 THE washtenawvoice.com April 15, 2013 The student publication of Washtenaw Community College Your voice. Your paper. Volume 19, Issue 16 Ann Arbor, Michigan Trustees FromVOICE behind bars to building cars double down Student shows what on Bellanca is possible by battling support challenging times Faculty union is By BENJAMIN KNAUSS ‘appreciative,’ but not Staff Writer very impressed When times get tough, life gives you exactly what you need, when you By BEN SOLIS need it, as long as you are paying at- Editor tention and not busy giving up. Eric Jiskra, a lab tech with the Washtenaw After months of holding their Community College Custom Cars & cards close to their collective chests, Concepts program, has a story to prove the Washtenaw Community College that. Trustees issued a formal statement “It’s really weird how the chain of of support for college President Rose events have been unfolding in my life Bellanca during its regularly sched- for the past few years,” said Jiskra, 34, uled public meeting on Tuesday. of Ypsilanti. “Four years ago I started The statement, tepid in tone and this program, but four years prior to written in the form of an open letter that I was in belly chains on my way from Board Chair Anne Williams, act- to prison.” ed as the board’s direct response to Jiskra worked in construction prior the myriad concerns brought forth by to being sent to prison for an alcohol the Washtenaw Community College BENJAMIN KNAUSS THE WASHTENAW VOICE related offense.