Chapter 4 the Electric Potential

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

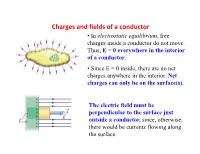

Charges and Fields of a Conductor • in Electrostatic Equilibrium, Free Charges Inside a Conductor Do Not Move

Charges and fields of a conductor • In electrostatic equilibrium, free charges inside a conductor do not move. Thus, E = 0 everywhere in the interior of a conductor. • Since E = 0 inside, there are no net charges anywhere in the interior. Net charges can only be on the surface(s). The electric field must be perpendicular to the surface just outside a conductor, since, otherwise, there would be currents flowing along the surface. Gauss’s Law: Qualitative Statement . Form any closed surface around charges . Count the number of electric field lines coming through the surface, those outward as positive and inward as negative. Then the net number of lines is proportional to the net charges enclosed in the surface. Uniformly charged conductor shell: Inside E = 0 inside • By symmetry, the electric field must only depend on r and is along a radial line everywhere. • Apply Gauss’s law to the blue surface , we get E = 0. •The charge on the inner surface of the conductor must also be zero since E = 0 inside a conductor. Discontinuity in E 5A-12 Gauss' Law: Charge Within a Conductor 5A-12 Gauss' Law: Charge Within a Conductor Electric Potential Energy and Electric Potential • The electrostatic force is a conservative force, which means we can define an electrostatic potential energy. – We can therefore define electric potential or voltage. .Two parallel metal plates containing equal but opposite charges produce a uniform electric field between the plates. .This arrangement is an example of a capacitor, a device to store charge. • A positive test charge placed in the uniform electric field will experience an electrostatic force in the direction of the electric field. -

Maxwell's Equations

Maxwell’s Equations Matt Hansen May 20, 2004 1 Contents 1 Introduction 3 2 The basics 3 2.1 Static charges . 3 2.2 Moving charges . 4 2.3 Magnetism . 4 2.4 Vector operations . 5 2.5 Calculus . 6 2.6 Flux . 6 3 History 7 4 Maxwell’s Equations 8 4.1 Maxwell’s Equations . 8 4.2 Gauss’ law for electricity . 8 4.3 Gauss’ law for magnetism . 10 4.4 Faraday’s law . 11 4.5 Ampere-Maxwell law . 13 5 Conclusion 14 2 1 Introduction If asked, most people outside a physics department would not be able to identify Maxwell’s equations, nor would they be able to state that they dealt with electricity and magnetism. However, Maxwell’s equations have many very important implications in the life of a modern person, so much so that people use devices that function off the principles in Maxwell’s equations every day without even knowing it. 2 The basics 2.1 Static charges In order to understand Maxwell’s equations, it is necessary to understand some basic things about electricity and magnetism first. Static electricity is easy to understand, in that it is just a charge which, as its name implies, does not move until it is given the chance to “escape” to the ground. Amounts of charge are measured in coulombs, abbreviated C. 1C is an extraordi- nary amount of charge, chosen rather arbitrarily to be the charge carried by 6.41418 · 1018 electrons. The symbol for charge in equations is q, sometimes with a subscript like q1 or qenc. -

Electro Magnetic Fields Lecture Notes B.Tech

ELECTRO MAGNETIC FIELDS LECTURE NOTES B.TECH (II YEAR – I SEM) (2019-20) Prepared by: M.KUMARA SWAMY., Asst.Prof Department of Electrical & Electronics Engineering MALLA REDDY COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING & TECHNOLOGY (Autonomous Institution – UGC, Govt. of India) Recognized under 2(f) and 12 (B) of UGC ACT 1956 (Affiliated to JNTUH, Hyderabad, Approved by AICTE - Accredited by NBA & NAAC – ‘A’ Grade - ISO 9001:2015 Certified) Maisammaguda, Dhulapally (Post Via. Kompally), Secunderabad – 500100, Telangana State, India ELECTRO MAGNETIC FIELDS Objectives: • To introduce the concepts of electric field, magnetic field. • Applications of electric and magnetic fields in the development of the theory for power transmission lines and electrical machines. UNIT – I Electrostatics: Electrostatic Fields – Coulomb’s Law – Electric Field Intensity (EFI) – EFI due to a line and a surface charge – Work done in moving a point charge in an electrostatic field – Electric Potential – Properties of potential function – Potential gradient – Gauss’s law – Application of Gauss’s Law – Maxwell’s first law, div ( D )=ρv – Laplace’s and Poison’s equations . Electric dipole – Dipole moment – potential and EFI due to an electric dipole. UNIT – II Dielectrics & Capacitance: Behavior of conductors in an electric field – Conductors and Insulators – Electric field inside a dielectric material – polarization – Dielectric – Conductor and Dielectric – Dielectric boundary conditions – Capacitance – Capacitance of parallel plates – spherical co‐axial capacitors. Current density – conduction and Convection current densities – Ohm’s law in point form – Equation of continuity UNIT – III Magneto Statics: Static magnetic fields – Biot‐Savart’s law – Magnetic field intensity (MFI) – MFI due to a straight current carrying filament – MFI due to circular, square and solenoid current Carrying wire – Relation between magnetic flux and magnetic flux density – Maxwell’s second Equation, div(B)=0, Ampere’s Law & Applications: Ampere’s circuital law and its applications viz. -

Electromagnetic Fields and Energy

MIT OpenCourseWare http://ocw.mit.edu Haus, Hermann A., and James R. Melcher. Electromagnetic Fields and Energy. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1989. ISBN: 9780132490207. Please use the following citation format: Haus, Hermann A., and James R. Melcher, Electromagnetic Fields and Energy. (Massachusetts Institute of Technology: MIT OpenCourseWare). http://ocw.mit.edu (accessed [Date]). License: Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike. Also available from Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, 1989. ISBN: 9780132490207. Note: Please use the actual date you accessed this material in your citation. For more information about citing these materials or our Terms of Use, visit: http://ocw.mit.edu/terms 8 MAGNETOQUASISTATIC FIELDS: SUPERPOSITION INTEGRAL AND BOUNDARY VALUE POINTS OF VIEW 8.0 INTRODUCTION MQS Fields: Superposition Integral and Boundary Value Views We now follow the study of electroquasistatics with that of magnetoquasistat ics. In terms of the flow of ideas summarized in Fig. 1.0.1, we have completed the EQS column to the left. Starting from the top of the MQS column on the right, recall from Chap. 3 that the laws of primary interest are Amp`ere’s law (with the displacement current density neglected) and the magnetic flux continuity law (Table 3.6.1). � × H = J (1) � · µoH = 0 (2) These laws have associated with them continuity conditions at interfaces. If the in terface carries a surface current density K, then the continuity condition associated with (1) is (1.4.16) n × (Ha − Hb) = K (3) and the continuity condition associated with (2) is (1.7.6). a b n · (µoH − µoH ) = 0 (4) In the absence of magnetizable materials, these laws determine the magnetic field intensity H given its source, the current density J. -

9 AP-C Electric Potential, Energy and Capacitance

#9 AP-C Electric Potential, Energy and Capacitance AP-C Objectives (from College Board Learning Objectives for AP Physics) 1. Electric potential due to point charges a. Determine the electric potential in the vicinity of one or more point charges. b. Calculate the electrical work done on a charge or use conservation of energy to determine the speed of a charge that moves through a specified potential difference. c. Determine the direction and approximate magnitude of the electric field at various positions given a sketch of equipotentials. d. Calculate the potential difference between two points in a uniform electric field, and state which point is at the higher potential. e. Calculate how much work is required to move a test charge from one location to another in the field of fixed point charges. f. Calculate the electrostatic potential energy of a system of two or more point charges, and calculate how much work is require to establish the charge system. g. Use integration to determine the electric potential difference between two points on a line, given electric field strength as a function of position on that line. h. State the relationship between field and potential, and define and apply the concept of a conservative electric field. 2. Electric potential due to other charge distributions a. Calculate the electric potential on the axis of a uniformly charged disk. b. Derive expressions for electric potential as a function of position for uniformly charged wires, parallel charged plates, coaxial cylinders, and concentric spheres. 3. Conductors a. Understand the nature of electric fields and electric potential in and around conductors. -

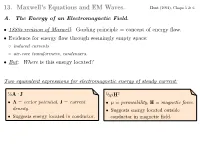

13. Maxwell's Equations and EM Waves. Hunt (1991), Chaps 5 & 6 A

13. Maxwell's Equations and EM Waves. Hunt (1991), Chaps 5 & 6 A. The Energy of an Electromagnetic Field. • 1880s revision of Maxwell: Guiding principle = concept of energy flow. • Evidence for energy flow through seemingly empty space: ! induced currents ! air-core transformers, condensers. • But: Where is this energy located? Two equivalent expressions for electromagnetic energy of steady current: ½A J ½µH2 • A = vector potential, J = current • µ = permeability, H = magnetic force. density. • Suggests energy located outside • Suggests energy located in conductor. conductor in magnetic field. 13. Maxwell's Equations and EM Waves. Hunt (1991), Chaps 5 & 6 A. The Energy of an Electromagnetic Field. • 1880s revision of Maxwell: Guiding principle = concept of energy flow. • Evidence for energy flow through seemingly empty space: ! induced currents ! air-core transformers, condensers. • But: Where is this energy located? Two equivalent expressions for electrostatic energy: ½qψ# ½εE2 • q = charge, ψ = electric potential. • ε = permittivity, E = electric force. • Suggests energy located in charged • Suggests energy located outside object. charged object in electric field. • Maxwell: Treated potentials A, ψ as fundamental quantities. Poynting's account of energy flux • Research project (1884): "How does the energy about an electric current pass from point to point -- that is, by what paths and acording to what law does it travel from the part of the circuit where it is first recognizable as electric and John Poynting magnetic, to the parts where it is changed into heat and other forms?" (1852-1914) • Solution: The energy flux at each point in space is encoded in a vector S given by S = E × H. -

Topic 2.3: Electric and Magnetic Fields

TOPIC 2.3: ELECTRIC AND MAGNETIC FIELDS S4P-2-13 Compare and contrast the inverse square nature of gravitational and electric fields. S4P-2-14 State Coulomb’s Law and solve problems for more than one electric force acting on a charge. Include: one and two dimensions S4P-2-15 Illustrate, using diagrams, how the charge distribution on two oppositely charged parallel plates results in a uniform field. S4P-2-16 Derive an equation for the electric potential energy between two oppositely ∆ charged parallel plates (Ee = qE d). S4P-2-17 Describe electric potential as the electric potential energy per unit charge. S4P-2-18 Identify the unit of electric potential as the volt. S4P-2-19 Define electric potential difference (voltage) and express the electric field between two oppositely charged parallel plates in terms of voltage and the separation ⎛ ∆V ⎞ between the plates ⎜ε = ⎟. ⎝ d ⎠ S4P-2-20 Solve problems for charges moving between or through parallel plates. S4P-2-21 Use hand rules to describe the directional relationships between electric and magnetic fields and moving charges. S4P-2-22 Describe qualitatively various technologies that use electric and magnetic fields. Examples: electromagnetic devices (such as a solenoid, motor, bell, or relay), cathode ray tube, mass spectrometer, antenna Topic 2: Fields • SENIOR 4 PHYSICS GENERAL LEARNING OUTCOME SPECIFIC LEARNING OUTCOME CONNECTION S4P-2-13: Compare and contrast the Students will… inverse square nature of Describe and appreciate the gravitational and electric fields. similarity and diversity of forms, functions, and patterns within the natural and constructed world (GLO E1) SUGGESTIONS FOR INSTRUCTION Entry Level Knowledge Notes to the Teacher The definition of gravitational fields around a point When examining the gravitational field of a mass, mass it is useful to view the mass as a point mass, irrespective of its size. -

Voltage and Electric Potential.Doc 1/6

10/26/2004 Voltage and Electric Potential.doc 1/6 Voltage and Electric Potential An important application of the line integral is the calculation of work. Say there is some vector field F (r )that exerts a force on some object. Q: How much work (W) is done by this vector field if the object moves from point Pa to Pb, along contour C ?? A: We can find out by evaluating the line integral: = ⋅ A Wab ∫F(r ) d C Pb C Pa Say this object is a charged particle with charge Q, and the force is applied by a static electric field E (r ). We know the force on the charged particle is: FE(rr) = Q ( ) Jim Stiles The Univ. of Kansas Dept. of EECS 10/26/2004 Voltage and Electric Potential.doc 2/6 and thus the work done by the electric field in moving a charged particle along some contour C is: Q: Oooh, I don’t like evaluating contour integrals; isn’t there W =⋅F r d A ab ∫ () some easier way? C =⋅Q ∫ E ()r d A C A: Yes there is! Recall that a static electric field is a conservative vector field. Therefore, we can write any electric field as the gradient of a specific scalar field V ()r : E (rr) = −∇V ( ) We can then evaluate the work integral as: =⋅A Wab Qd∫E(r ) C =−QV∫ ∇()r ⋅ dA C =−QV⎣⎡ ()rrba − V()⎦⎤ =−QV⎣⎡ ()rrab V()⎦⎤ Jim Stiles The Univ. of Kansas Dept. of EECS 10/26/2004 Voltage and Electric Potential.doc 3/6 We define: VabVr( a) − Vr( b ) Therefore: Wab= QV ab Q: So what the heck is Vab ? Does it mean any thing? Do we use it in engineering? A: First, consider what Wab is! The value Wab represents the work done by the electric field on charge Q when moving it from point Pa to point Pb. -

At Equilibrium Under Electrostatic Conditions, Any Excess Charge Resides on the Surface of a Conductor

The Electric Field Inside a Conductor: Shielding At equilibrium under electrostatic conditions, any excess charge resides on the surface of a conductor. At equilibrium under electrostatic conditions, the electric field is zero at any point within a conducting material. The conductor shields any charge within it from electric fields created outside the conductor. The Electric Field Inside a Conductor: Shielding The electric field just outside the surface of a conductor is perpendicular to the surface at equilibrium under electrostatic conditions. Chapter 17 Electric Potential Potential Energy The work done by the gravitational field on the ball in going from A to B equals the difference between the gravitational potential energy at A (GPEA) and the gravitational potential energy at B (GPEB) WBA = mghA − mghB = GPE A − GPEB Potential Energy Analogous situation between the work done by the gravitational field on the ball and the work done by the electric field on the charge. Potential Energy The work done by the electric field on the charge in going from A to B equals the difference between the electric potential energy at A (EPEA) and the electric potential energy at B (EPEB) WBA = EPE A − EPEB Note that the electric force is a conservative force just like the gravitational force so the work done by it is independent of the path taken between A and B. The Electric Potential Difference W EPE EPE BA = A − B qo qo qo The potential energy per unit charge is called the electric potential. The Electric Potential Difference DEFINITION OF ELECTRIC -

Chapter 20: Electric Potential and Electric Potential Energy 2

Chapter 20: Electric Potential and Electric Potential Energy 2. A 4.5 µC charge moves in a uniform electric field Ex=(4.1 × 105 N/C) ˆ . The change in electric potential energy of a charge that moves against an electric field is given by equation 20-1, ∆=U q0 Ed . If the charge moves in the same direction as the field, the work done by the field is positive and ∆=−=−=−U W Fd q0 Ed . If the charge moves in a direction perpendicular to the field, the work and change in potential energy are both zero. The change in potential energy from point A to point B is independent of the path the charge takes between those two points. 1. (a) The charge moves ∆=U 0 perpendicular to the field: 2. (b) The charge moves in the − ∆=−U q Ed =−×4.5 1065 C 4.1 × 10 N/C 6.0m=− 11 J same direction as the field: 0 ( )( )( ) 3. (c) The potential energy changes by an amount ∆=−U 0 11 J =−11 J equal to the sum of paths 1 and 2 above: 9. The vertical electric field of the earth creates a potential difference between two different heights. Because the electric field is uniform, the magnitude potential difference is simply the product of the field and the distance ∆s in the direction of the field (equation 20-4). Solve equation 20-4 for ∆V : ∆V = Es ∆=(100 V/m)( 555 ft× 0.305 m/ft) = 2 × 104 V = 20 kV 11. A potential difference across the gap of a spark plug produces a sufficiently large electric field to produce a spark. -

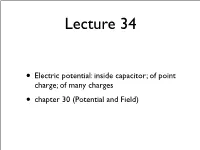

• Electric Potential: Inside Capacitor; of Point Charge; of Many Charges • Chapter 30 (Potential and Field) Electric Potential Inside a Parallel Plate Capacitor

Lecture 34 • Electric potential: inside capacitor; of point charge; of many charges • chapter 30 (Potential and Field) Electric Potential inside a Parallel Plate Capacitor E = η due to source charges on plates • "0 U = U = qEs elec q+sources ⇒ ∆Vc potential difference: ∆Vc = V+ V = Ed; E = ( 1 N/C = 1 V/m ) • − − d V = ∆VC (d x) (decreases from positive to negative plate) d − • electric field vectors to (imaginary) equipotential surfaces/ contour lines; potential⊥ decreases along direction of E choice of zero of potential (V + or V = 0 or... ): no physical difference • − Electric Potential of Point Charge; Charged Sphere qq! Uq+q = ! 4π"0r ⇒ (scalar vs. vector E 1/r2) ∝ • 4 graphical representations • Outside sphere (same as point charge at center):V = 1 Q ; r R 4π"0 r ≥ • In terms of potential at surface, V = V (at r = R)= Q : 0 4π"0R R Q =4π"0RV0 and V = r V0 Electric Potential of Many Charges Principle of superposition (like for E): V = 1 qi • i 4π"0 ri • Continuous distribution of charge (like for E,! easier due to scalar) model as simple shape, uniform charge distribution draw picture...identify P where V to be calculated... divide Q into ∆ Q (shapes for which V known) V= i Vi ∆Q charge density dx Sum→! integral × → Potential of Ring of Charge ri same for all charge segments N N 1 ∆Q 1 1 N V = Vi = = ∆Q i=1 i=1 4π"0 ri 4π"0 √R2+z2 i=1 No need for integral: N ∆Q = Q ! ! i=1 ⇒ ! V = 1 Q ring on axis 4π"0!√R2+z2 Check: z R Vring Q/ (4π"0z) (point charge," as⇒ expected)≈ Potential of Disk of Charge uniform surface charge density η = Q/A = Q/ πR2 Use potential of ring V = 1 ∆Qi i 4π"0 2 2 √ri +z ! " V = V = 1 N ∆Q i=1 i 4π"0 i=1 2 2 √ri +z ∆Qi #= η∆Ai; ∆Ai =2#πri∆r 1 N 2Q ri∆ri Q R rdr V = 2 2 4π"0 i=1 R 2 2 2π"0R 0 √r2+z2 √ri +z → 2 2 Q 2 2 Charge of# variables: u = r + z .. -

Chapter 17 Electric Potential

Chapter 17 Electric Potential The Electric Potential Difference Created by Point Charges When two or more charges are present, the potential due to all of the charges is obtained by adding together the individual potentials. Example: The Total Electric Potential At locations A and B, find the total electric potential. The Electric Potential Difference Created by Point Charges 8.99×109 N ⋅m2 C2 + 8.0×10−-98 C 8.99×109 N ⋅m2 C2 −8.0×10−-98 C V = ( )( )+ ( )( )= +240 V A 0.20 m 0.60 m 8.99×109 N ⋅m2 C2 + 8.0×10−-98 C 8.99×109 N ⋅m2 C2 −8.0×10-9−8 C V = ( )( )+ ( )( )= 0 V B 0.40 m 0.40 m Equipotential Surfaces and Their Relation to the Electric Field An equipotential surface is a surface on which the electric potential is the same everywhere. Equipotential surfaces for kq a point charge (concentric V = r spheres centered on the charge) The net electric force does no work on a charge as it moves on an equipotential surface. Equipotential Surfaces and Their Relation to the Electric Field The electric field created by any charge or group of charges is everywhere perpendicular to the associated equipotential surfaces and points in the direction of decreasing potential. In equilibrium, conductors are always equipotential surfaces. Equipotential Surfaces and Their Relation to the Electric Field Lines of force and equipotential surfaces for a charge dipole. Equipotential Surfaces and Their Relation to the Electric Field The electric field can be shown to be related to the electric potential.