19 Electric Potential and Electric Field

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Printer Tech Tips—Cause & Effects of Static Electricity in Paper

Printer Tech Tips Cause & Effects of Static Electricity in Paper Problem The paper has developed a static electrical charge causing an abnormal sheet-to- sheet or sheet-to-material attraction which is difficult to separate. This condition may result in feeder trip-offs, print voids from surface contamination, ink offset, Sappi Printer Technical Service or poor sheet jog in the delivery. 877 SappiHelp (727 7443) Description Static electricity is defined as a non-moving, non-flowing electrical charge or in simple terms, electricity at rest. Static electricity becomes visible and dynamic during the brief moment it sparks a discharge and for that instant it’s no longer at rest. Lightning is the result of static discharge as is the shock you receive just before contacting a grounded object during unusually dry weather. Matter is composed of atoms, which in turn are composed of protons, neutrons, and electrons. The number of protons and neutrons, which make up the atoms nucleus, determine the type of material. Electrons orbit the nucleus and balance the electrical charge of the protons. When both negative and positive are equal, the charge of the balanced atom is neutral. If electrons are removed or added to this configuration, the overall charge becomes either negative or positive resulting in an unbalanced atom. Materials with high conductivity, such as steel, are called conductors and maintain neutrality because their electrons can move freely from atom to atom to balance any applied charges. Therefore, conductors can dissipate static when properly grounded. Non-conductive materials, or insulators such as plastic and wood, have the opposite property as their electrons can not move freely to maintain balance. -

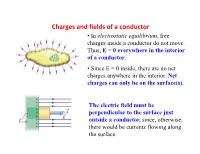

Charges and Fields of a Conductor • in Electrostatic Equilibrium, Free Charges Inside a Conductor Do Not Move

Charges and fields of a conductor • In electrostatic equilibrium, free charges inside a conductor do not move. Thus, E = 0 everywhere in the interior of a conductor. • Since E = 0 inside, there are no net charges anywhere in the interior. Net charges can only be on the surface(s). The electric field must be perpendicular to the surface just outside a conductor, since, otherwise, there would be currents flowing along the surface. Gauss’s Law: Qualitative Statement . Form any closed surface around charges . Count the number of electric field lines coming through the surface, those outward as positive and inward as negative. Then the net number of lines is proportional to the net charges enclosed in the surface. Uniformly charged conductor shell: Inside E = 0 inside • By symmetry, the electric field must only depend on r and is along a radial line everywhere. • Apply Gauss’s law to the blue surface , we get E = 0. •The charge on the inner surface of the conductor must also be zero since E = 0 inside a conductor. Discontinuity in E 5A-12 Gauss' Law: Charge Within a Conductor 5A-12 Gauss' Law: Charge Within a Conductor Electric Potential Energy and Electric Potential • The electrostatic force is a conservative force, which means we can define an electrostatic potential energy. – We can therefore define electric potential or voltage. .Two parallel metal plates containing equal but opposite charges produce a uniform electric field between the plates. .This arrangement is an example of a capacitor, a device to store charge. • A positive test charge placed in the uniform electric field will experience an electrostatic force in the direction of the electric field. -

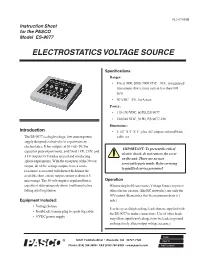

Electrostatics Voltage Source

012-07038B Instruction Sheet for the PASCO Model ES-9077 ELECTROSTATICS VOLTAGE SOURCE Specifications Ranges: • Fixed 1000, 2000, 3000 VDC ±10%, unregulated (maximum short circuit current less than 0.01 mA). • 30 VDC ±5%, 1mA max. Power: • 110-130 VDC, 60 Hz, ES-9077 • 220/240 VDC, 50 Hz, ES-9077-220 Dimensions: Introduction • 5 1/2” X 5” X 1”, plus AC adapter and red/black The ES-9077 is a high voltage, low current power cable set supply designed exclusively for experiments in electrostatics. It has outputs at 30 volts DC for IMPORTANT: To prevent the risk of capacitor plate experiments, and fixed 1 kV, 2 kV, and electric shock, do not remove the cover 3 kV outputs for Faraday ice pail and conducting on the unit. There are no user sphere experiments. With the exception of the 30 volt serviceable parts inside. Refer servicing output, all of the voltage outputs have a series to qualified service personnel. resistance associated with them which limit the available short-circuit output current to about 8.3 microamps. The 30 volt output is regulated but is Operation capable of delivering only about 1 milliamp before When using the Electrostatics Voltage Source to power falling out of regulation. other electric circuits, (like RC networks), use only the 30V output (Remember that the maximum drain is 1 Equipment Included: mA.). • Voltage Source Use the special high-voltage leads that are supplied with • Red/black, banana plug to spade lug cable the ES-9077 to make connections. Use of other leads • 9 VDC power supply may allow significant leakage from the leads to ground and negatively affect output voltage accuracy. -

A Review of Energy Storage Technologies' Application

sustainability Review A Review of Energy Storage Technologies’ Application Potentials in Renewable Energy Sources Grid Integration Henok Ayele Behabtu 1,2,* , Maarten Messagie 1, Thierry Coosemans 1, Maitane Berecibar 1, Kinde Anlay Fante 2 , Abraham Alem Kebede 1,2 and Joeri Van Mierlo 1 1 Mobility, Logistics, and Automotive Technology Research Centre, Vrije Universiteit Brussels, Pleinlaan 2, 1050 Brussels, Belgium; [email protected] (M.M.); [email protected] (T.C.); [email protected] (M.B.); [email protected] (A.A.K.); [email protected] (J.V.M.) 2 Faculty of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Jimma Institute of Technology, Jimma University, Jimma P.O. Box 378, Ethiopia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +32-485659951 or +251-926434658 Received: 12 November 2020; Accepted: 11 December 2020; Published: 15 December 2020 Abstract: Renewable energy sources (RESs) such as wind and solar are frequently hit by fluctuations due to, for example, insufficient wind or sunshine. Energy storage technologies (ESTs) mitigate the problem by storing excess energy generated and then making it accessible on demand. While there are various EST studies, the literature remains isolated and dated. The comparison of the characteristics of ESTs and their potential applications is also short. This paper fills this gap. Using selected criteria, it identifies key ESTs and provides an updated review of the literature on ESTs and their application potential to the renewable energy sector. The critical review shows a high potential application for Li-ion batteries and most fit to mitigate the fluctuation of RESs in utility grid integration sector. -

The Lorentz Force

CLASSICAL CONCEPT REVIEW 14 The Lorentz Force We can find empirically that a particle with mass m and electric charge q in an elec- tric field E experiences a force FE given by FE = q E LF-1 It is apparent from Equation LF-1 that, if q is a positive charge (e.g., a proton), FE is parallel to, that is, in the direction of E and if q is a negative charge (e.g., an electron), FE is antiparallel to, that is, opposite to the direction of E (see Figure LF-1). A posi- tive charge moving parallel to E or a negative charge moving antiparallel to E is, in the absence of other forces of significance, accelerated according to Newton’s second law: q F q E m a a E LF-2 E = = 1 = m Equation LF-2 is, of course, not relativistically correct. The relativistically correct force is given by d g mu u2 -3 2 du u2 -3 2 FE = q E = = m 1 - = m 1 - a LF-3 dt c2 > dt c2 > 1 2 a b a b 3 Classically, for example, suppose a proton initially moving at v0 = 10 m s enters a region of uniform electric field of magnitude E = 500 V m antiparallel to the direction of E (see Figure LF-2a). How far does it travel before coming (instanta> - neously) to rest? From Equation LF-2 the acceleration slowing the proton> is q 1.60 * 10-19 C 500 V m a = - E = - = -4.79 * 1010 m s2 m 1.67 * 10-27 kg 1 2 1 > 2 E > The distance Dx traveled by the proton until it comes to rest with vf 0 is given by FE • –q +q • FE 2 2 3 2 vf - v0 0 - 10 m s Dx = = 2a 2 4.79 1010 m s2 - 1* > 2 1 > 2 Dx 1.04 10-5 m 1.04 10-3 cm Ϸ 0.01 mm = * = * LF-1 A positively charged particle in an electric field experiences a If the same proton is injected into the field perpendicular to E (or at some angle force in the direction of the field. -

Quantum Mechanics Electromotive Force

Quantum Mechanics_Electromotive force . Electromotive force, also called emf[1] (denoted and measured in volts), is the voltage developed by any source of electrical energy such as a batteryor dynamo.[2] The word "force" in this case is not used to mean mechanical force, measured in newtons, but a potential, or energy per unit of charge, measured involts. In electromagnetic induction, emf can be defined around a closed loop as the electromagnetic workthat would be transferred to a unit of charge if it travels once around that loop.[3] (While the charge travels around the loop, it can simultaneously lose the energy via resistance into thermal energy.) For a time-varying magnetic flux impinging a loop, theElectric potential scalar field is not defined due to circulating electric vector field, but nevertheless an emf does work that can be measured as a virtual electric potential around that loop.[4] In a two-terminal device (such as an electrochemical cell or electromagnetic generator), the emf can be measured as the open-circuit potential difference across the two terminals. The potential difference thus created drives current flow if an external circuit is attached to the source of emf. When current flows, however, the potential difference across the terminals is no longer equal to the emf, but will be smaller because of the voltage drop within the device due to its internal resistance. Devices that can provide emf includeelectrochemical cells, thermoelectric devices, solar cells and photodiodes, electrical generators,transformers, and even Van de Graaff generators.[4][5] In nature, emf is generated whenever magnetic field fluctuations occur through a surface. -

Estimation of the Dissipation Rate of Turbulent Kinetic Energy: a Review

Chemical Engineering Science 229 (2021) 116133 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Chemical Engineering Science journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ces Review Estimation of the dissipation rate of turbulent kinetic energy: A review ⇑ Guichao Wang a, , Fan Yang a,KeWua, Yongfeng Ma b, Cheng Peng c, Tianshu Liu d, ⇑ Lian-Ping Wang b,c, a SUSTech Academy for Advanced Interdisciplinary Studies, Southern University of Science and Technology, Shenzhen 518055, PR China b Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Turbulence Research and Applications, Center for Complex Flows and Soft Matter Research and Department of Mechanics and Aerospace Engineering, Southern University of Science and Technology, Shenzhen 518055, Guangdong, China c Department of Mechanical Engineering, 126 Spencer Laboratory, University of Delaware, Newark, DE 19716-3140, USA d Department of Mechanical and Aeronautical Engineering, Western Michigan University, Kalamazoo, MI 49008, USA highlights Estimate of turbulent dissipation rate is reviewed. Experimental works are summarized in highlight of spatial/temporal resolution. Data processing methods are compared. Future directions in estimating turbulent dissipation rate are discussed. article info abstract Article history: A comprehensive literature review on the estimation of the dissipation rate of turbulent kinetic energy is Received 8 July 2020 presented to assess the current state of knowledge available in this area. Experimental techniques (hot Received in revised form 27 August 2020 wires, LDV, PIV and PTV) reported on the measurements of turbulent dissipation rate have been critically Accepted 8 September 2020 analyzed with respect to the velocity processing methods. Traditional hot wires and LDV are both a point- Available online 12 September 2020 based measurement technique with high temporal resolution and Taylor’s frozen hypothesis is generally required to transfer temporal velocity fluctuations into spatial velocity fluctuations in turbulent flows. -

Turbulence Kinetic Energy Budgets and Dissipation Rates in Disturbed Stable Boundary Layers

4.9 TURBULENCE KINETIC ENERGY BUDGETS AND DISSIPATION RATES IN DISTURBED STABLE BOUNDARY LAYERS Julie K. Lundquist*1, Mark Piper2, and Branko Kosovi1 1Atmospheric Science Division Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, Livermore, CA, 94550 2Program in Atmospheric and Oceanic Science, University of Colorado at Boulder 1. INTRODUCTION situated in gently rolling farmland in eastern Kansas, with a homogeneous fetch to the An important parameter in the numerical northwest. The ASTER facility, operated by the simulation of atmospheric boundary layers is the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) dissipation length scale, lε. It is especially Atmospheric Technology Division, was deployed to important in weakly to moderately stable collect turbulence data. The ASTER sonic conditions, in which a tenuous balance between anemometers were used to compute turbulence shear production of turbulence, buoyant statistics for the three velocity components and destruction of turbulence, and turbulent dissipation used to estimate dissipation rate. is maintained. In large-scale models, the A dry Arctic cold front passed the dissipation rate is often parameterized using a MICROFRONTS site at approximately 0237 UTC diagnostic equation based on the production of (2037 LST) 20 March 1995, two hours after local turbulent kinetic energy (TKE) and an estimate of sunset at 1839 LST. Time series spanning the the dissipation length scale. Proper period 0000-0600 UTC are shown in Figure 1.The parameterization of the dissipation length scale 6-hr time period was chosen because it allows from experimental data requires accurate time for the front to completely pass the estimation of the rate of dissipation of TKE from instrumented tower, with time on either side to experimental data. -

Maxwell's Equations

Maxwell’s Equations Matt Hansen May 20, 2004 1 Contents 1 Introduction 3 2 The basics 3 2.1 Static charges . 3 2.2 Moving charges . 4 2.3 Magnetism . 4 2.4 Vector operations . 5 2.5 Calculus . 6 2.6 Flux . 6 3 History 7 4 Maxwell’s Equations 8 4.1 Maxwell’s Equations . 8 4.2 Gauss’ law for electricity . 8 4.3 Gauss’ law for magnetism . 10 4.4 Faraday’s law . 11 4.5 Ampere-Maxwell law . 13 5 Conclusion 14 2 1 Introduction If asked, most people outside a physics department would not be able to identify Maxwell’s equations, nor would they be able to state that they dealt with electricity and magnetism. However, Maxwell’s equations have many very important implications in the life of a modern person, so much so that people use devices that function off the principles in Maxwell’s equations every day without even knowing it. 2 The basics 2.1 Static charges In order to understand Maxwell’s equations, it is necessary to understand some basic things about electricity and magnetism first. Static electricity is easy to understand, in that it is just a charge which, as its name implies, does not move until it is given the chance to “escape” to the ground. Amounts of charge are measured in coulombs, abbreviated C. 1C is an extraordi- nary amount of charge, chosen rather arbitrarily to be the charge carried by 6.41418 · 1018 electrons. The symbol for charge in equations is q, sometimes with a subscript like q1 or qenc. -

Capacitance and Dielectrics Capacitance

Capacitance and Dielectrics Capacitance General Definition: C === q /V Special case for parallel plates: εεε A C === 0 d Potential Energy • I must do work to charge up a capacitor. • This energy is stored in the form of electric potential energy. Q2 • We showed that this is U === 2C • Then we saw that this energy is stored in the electric field, with a volume energy density 1 2 u === 2 εεε0 E Potential difference and Electric field Since potential difference is work per unit charge, b ∆∆∆V === Edx ∫∫∫a For the parallel-plate capacitor E is uniform, so V === Ed Also for parallel-plate case Gauss’s Law gives Q Q εεε0 A E === σσσ /εεε0 === === Vd so C === === εεε0 A V d Spherical example A spherical capacitor has inner radius a = 3mm, outer radius b = 6mm. The charge on the inner sphere is q = 2 C. What is the potential difference? kq From Gauss’s Law or the Shell E === Theorem, the field inside is r 2 From definition of b kq 1 1 V === dr === kq −−− potential difference 2 ∫∫∫a r a b 1 1 1 1 === 9 ×××109 ××× 2 ×××10−−−9 −−− === 18 ×××103 −−− === 3 ×××103 V −−−3 −−−3 3 ×××10 6 ×××10 3 6 What is the capacitance? C === Q /V === 2( C) /(3000V ) === 7.6 ×××10−−−4 F A capacitor has capacitance C = 6 µF and charge Q = 2 nC. If the charge is Q.25-1 increased to 4 nC what will be the new capacitance? (1) 3 µF (2) 6 µF (3) 12 µF (4) 24 µF Q. -

Electro Magnetic Fields Lecture Notes B.Tech

ELECTRO MAGNETIC FIELDS LECTURE NOTES B.TECH (II YEAR – I SEM) (2019-20) Prepared by: M.KUMARA SWAMY., Asst.Prof Department of Electrical & Electronics Engineering MALLA REDDY COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING & TECHNOLOGY (Autonomous Institution – UGC, Govt. of India) Recognized under 2(f) and 12 (B) of UGC ACT 1956 (Affiliated to JNTUH, Hyderabad, Approved by AICTE - Accredited by NBA & NAAC – ‘A’ Grade - ISO 9001:2015 Certified) Maisammaguda, Dhulapally (Post Via. Kompally), Secunderabad – 500100, Telangana State, India ELECTRO MAGNETIC FIELDS Objectives: • To introduce the concepts of electric field, magnetic field. • Applications of electric and magnetic fields in the development of the theory for power transmission lines and electrical machines. UNIT – I Electrostatics: Electrostatic Fields – Coulomb’s Law – Electric Field Intensity (EFI) – EFI due to a line and a surface charge – Work done in moving a point charge in an electrostatic field – Electric Potential – Properties of potential function – Potential gradient – Gauss’s law – Application of Gauss’s Law – Maxwell’s first law, div ( D )=ρv – Laplace’s and Poison’s equations . Electric dipole – Dipole moment – potential and EFI due to an electric dipole. UNIT – II Dielectrics & Capacitance: Behavior of conductors in an electric field – Conductors and Insulators – Electric field inside a dielectric material – polarization – Dielectric – Conductor and Dielectric – Dielectric boundary conditions – Capacitance – Capacitance of parallel plates – spherical co‐axial capacitors. Current density – conduction and Convection current densities – Ohm’s law in point form – Equation of continuity UNIT – III Magneto Statics: Static magnetic fields – Biot‐Savart’s law – Magnetic field intensity (MFI) – MFI due to a straight current carrying filament – MFI due to circular, square and solenoid current Carrying wire – Relation between magnetic flux and magnetic flux density – Maxwell’s second Equation, div(B)=0, Ampere’s Law & Applications: Ampere’s circuital law and its applications viz. -

Measuring Electricity Voltage Current Voltage Current

Measuring Electricity Electricity makes our lives easier, but it can seem like a mysterious force. Measuring electricity is confusing because we cannot see it. We are familiar with terms such as watt, volt, and amp, but we do not have a clear understanding of these terms. We buy a 60-watt lightbulb, a tool that needs 120 volts, or a vacuum cleaner that uses 8.8 amps, and dont think about what those units mean. Using the flow of water as an analogy can make Voltage electricity easier to understand. The flow of electrons in a circuit is similar to water flowing through a hose. If you could look into a hose at a given point, you would see a certain amount of water passing that point each second. The amount of water depends on how much pressure is being applied how hard the water is being pushed. It also depends on the diameter of the hose. The harder the pressure and the larger the diameter of the hose, the more water passes each second. The flow of electrons through a wire depends on the electrical pressure pushing the electrons and on the Current cross-sectional area of the wire. The flow of electrons can be compared to the flow of Voltage water. The water current is the number of molecules flowing past a fixed point; electrical current is the The pressure that pushes electrons in a circuit is number of electrons flowing past a fixed point. called voltage. Using the water analogy, if a tank of Electrical current (I) is defined as electrons flowing water were suspended one meter above the ground between two points having a difference in voltage.