Dimensions of Negligence in Criminal and Tort Law

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Page 243 TITLE 19—CUSTOMS DUTIES § 1592 Possible for Such

Page 243 TITLE 19—CUSTOMS DUTIES § 1592 possible for such merchandise, or any part (4) The external display of false registration thereof, to be introduced into the United numbers, false country of registration, or, in States unlawfully. the case of a vessel, false vessel name. (c) Civil penalties (5) The presence on board of unmanifested merchandise, the importation of which is pro- Any person who violates any provision of this hibited or restricted. section is liable for a civil penalty equal to (6) The presence on board of controlled sub- twice the value of the merchandise involved in stances which are not manifested or which are the violation, but not less than $10,000. The not accompanied by the permits or licenses re- value of any controlled substance included in quired under Single Convention on Narcotic the merchandise shall be determined in accord- Drugs or other international treaty. ance with section 1497(b) of this title. (7) The presence of any compartment or (d) Criminal penalties equipment which is built or fitted out for smuggling. In addition to being liable for a civil penalty (8) The failure of a vessel to stop when under subsection (c) of this section, any person hailed by a customs officer or other govern- who intentionally commits a violation of any ment authority. provision of this section is, upon conviction— (1) liable for a fine of not more than $10,000 (June 17, 1930, ch. 497, title IV, § 590, as added or imprisonment for not more than 5 years, or Pub. L. 99–570, title III, § 3120, Oct. -

Torts in the Oil Patch

Torts in the Oil Patch Prof. Tracy Hester September 11, 2017 Announcements • Field trip to Weatherford drilling rig: Friday, Sept. 29, 2017 • Guest speakers – – Dr. John Nielsen-Gammon, Wednesday, Sept. 13, at 6 pm in BLB 109 – Roger Martella, GE VP for EHS, Wednesday, Oct. 25, time and place TBA – Dr. Gavin Clarkson - November • IEL, AIPN, GCPA Review • Basics of Oilfield E&P • Types of contamination created by E&P work • Categories of likely tort actions • Reasons to pursue tort remedy rather than agency action Environmental Law of First Resort: Tort Claims • Nuisance • Negligence (including negligence per se) • Trespass • Unjust Enrichment • Emotional Distress • Strict Liability – Ultrahazardous Activity • Exotic claims (business torts, civil conspiracy) Likely Parties • Plaintiffs: – Surface estate owners – Neighbors – both surface and mineral estate owners – Agencies and governments – NGOs • Defendants: working interest owners, operators and contractors Duties Owed by Oil Company • Be a reasonably prudent operator • “Restore” the surface ? • plow depth • concrete pads and foundations? • oil, saltwater, etc. contamination? • What else does the lease (contract) say? Nuisance • Material or substantial injury to a person of ordinary health and sensibilities in that particular locale – private vs public nuisance • no statute of limitations if public nuisance • diminution in property value vs injunction or abatement (cost) • yesterday’s economic accommodation may become tomorrow’s nuisance (Texas: to persons of “ordinary” sensibilities) • Permit to discharge is usually not a defense • Permanent, temporary, and/or continuing • “Coming to the nuisance” doctrine may not be applicable if “temporary” and “continuing” Trespass • Conduct that leads to the invasion of a person’s interest in his or her rightful exclusive possession of property • La: unlawful physical invasion of property of another • Typically, intentional tort that requires a showing of fault • Often 2 or 3 year SOL. -

Proof of Fault in Media Defamation Litigation

Vanderbilt Law Review Volume 38 Issue 2 Issue 2 - March 1985 Article 1 3-1985 Proof of Fault in Media Defamation Litigation Lackland H. Bloom, Jr. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr Part of the Torts Commons Recommended Citation Lackland H. Bloom, Jr., Proof of Fault in Media Defamation Litigation, 38 Vanderbilt Law Review 247 (1985) Available at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr/vol38/iss2/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vanderbilt Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VANDERBILT LAW REVIEW VOLUME 38 MARCH 1985 NUMBER 2 Proof of Fault in Media Defamation Litigation Lackland H. Bloom, Jr.* I. INTRODUCTION ..................................... 249 II. ACTUAL MALICE .................................... 255 A. Clear and Convincing Evidence ............. 255 B. Knowledge of Falsity ...................... 256 C. Reckless Disregardfor the Truth ........... 259 1. Il1 W ill .............................. 260 2. Failure to Investigate or Verify ........ 264 (a) Lead Time .................... 267 (b) Seriousness of the Charge....... 270 (c) Inherent Improbability ......... 273 (d) Awareness of Inconsistent Infor- m ation ........................ 275 (e) No Source ..................... 277 (f) Obvious Reason to Doubt Source 278 (g) Failure to Consult an Obvious Source ........................ 283 (h) Failure to Consult an Expert ... 285 (i) No Further Verification Following Denial ........................ 286 * Associate Professor of Law, Southern Methodist University. B.A. 1970, Southern Methodist University; J.D. 1973, University of Michigan. I wish to thank Marilyn Lahr, J.D. 1986, Southern Methodist University School of Law, for her valuable assistance and the Southern Methodist University School of Law for its generous support. -

Res Ipsa Loquitur and Gross Negligence

RES IPSA LOQUITUR AND GROSS NEGLIGENCE I N A DICTUM in the recent case of Garland v.Greenspan,' the Supreme Court of Nevada echoed an apparently unanimous rule2 that the doc- trine of res ipsa loquitur will not raise an inference3 of gross negligence. The facts as found by the trial court sitting without a jury showed that one of the plaintiffs4 was injured when the defendants' automobile swerved to the left of the highway and then to the right, overturning on striking the right shoulder. The defendant driver had lost control of her car for "some unexplained reason" after passing another automobile at a speed in excess of sixty-five miles an hour and in returning to the right-hand line while negotiating a turn to the right. Under the Nevada statute,6 a guest passenger can recover in tort from the host driver only where injury was caused by the driver's in- toxication, wilful misconduct, or gross negligence. The Supreme Court of Nevada, affirming the judgment of the trial court, held that gross neg- ligence or wilful misconduct had not been established as a matter of law, '_Nev.-, 323 P.±d 27 (1958). 'See Harlan v. Taylor, z39 Cal. App. 30, 33 P.zd 422 (934); Lincoln v. Quick, 133 Cal. App. 433, 24 P.2d 245 (1933); O'Reilly v. Sattler, x4i Fla. 770, 193 So. 817 (1940); Minkovitz v. Fine, 67 Ga. App. 176, i9 S.E.zd 561 (1942); Rupe v. Smith, x~i Kan. 6o6, 323 P.zd 293 (x957); Winslow v. Tibbetts, 231 Me. -

Fraud and Scams: a Moving Picture

issue 145 August 2018 1 ombudsman news essential reading for people interested in financial complaints – and how to prevent or settle them fraud and scams: a moving picture It was only relatively recently, in 2015, that we shared our insight into banking complaints involving phone fraud. Back then, it seemed the fact older people were more likely to use landlines meant they were particularly at risk of “no hang up” scams. Caroline Wayman chief ombudsman Today, it’s often loopholes in This makes it harder for us to And as our case studies show, in this issue new technologies, rather than reach an answer both sides are the evolution of criminals’ in old ones, that fraudsters happy with. But it doesn’t mean methods – in particular, ombudsman are using to their advantage. usual standards don’t apply. As their sophisticated use of focus: fraud and Your first step toward being our case studies illustrate, we’ll technology and manipulative scams scammed may be putting your expect to see clear evidence “social engineering” – means page 3 details into an identical, but that banks have investigated it’s an increasingly difficult fake banking website – or thoroughly – and reflected hard case to make. fraud and scams responding to a text message on what more might have been case studies that, on the face of it, looks like done to protect their customers page 8 it’s from your bank. and their money. first quarter Unlike most other complaints We also often hear from banks statistics we see, complaints about fraud that their customers have acted page 14 and scams involve – whether with “gross negligence” – and it’s accepted or suspected – this means they’re not liable for Q&A – our new the actions of a criminal third the money their customer has case-handling party. -

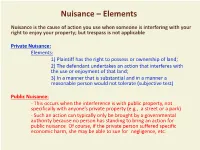

Nuisance – Elements

Nuisance – Elements Nuisance is the cause of action you use when someone is interfering with your right to enjoy your property; but trespass is not applicable Private Nuisance: Elements: 1) Plaintiff has the right to possess or ownership of land; 2) The defendant undertakes an action that interferes with the use or enjoyment of that land; 3) In a manner that is substantial and in a manner a reasonable person would not tolerate (subjective test) Public Nuisance: - This occurs when the interference is with public property, not specifically with anyone’s private property (e.g., a street or a park) - Such an action can typically only be brought by a governmental authority because no person has standing to bring an action for public nuisance. Of course, if the private person suffered specific economic harm, she may be able to sue for negligence, etc. Nuisance - Other Factors - The nuisance must have arisen from an act that’s actionable as an intentional, negligent or strict liability tort! - The actions that give rise to the nuisance must be “unreasonable” under the circumstances. Thus: A “balancing test” must be performed between the harm that the nuisance causes and the benefits of the activities that create the nuisance, taking into account: o The economic and social importance of the activity o The burden on the defendant and on society of forcing the activity to cease o Whether there is a more appropriate place to conduct the activity - All the rules regarding causation and damages apply, as with negligence and strict liability - The defenses of assumption of risk and contributory negligence apply; as with any other tort. -

Gross Negligence Or Willful Misconduct" Patrick H

Louisiana Law Review Volume 71 | Number 3 Spring 2011 The BP piS ll and the Meaning of "Gross Negligence or Willful Misconduct" Patrick H. Martin Louisiana State University Law Center Repository Citation Patrick H. Martin, The BP Spill and the Meaning of "Gross Negligence or Willful Misconduct", 71 La. L. Rev. (2011) Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/lalrev/vol71/iss3/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at LSU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Louisiana Law Review by an authorized editor of LSU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The BP Spill and the Meaning of "Gross Negligence or Wilful Misconduct" PatrickH. Martin* INTRODUCTION The blowout of the Macondo well on April 20, 2010 and the resulting escape of oil into the waters of the Gulf of Mexico and onto the shores of coastal states set in motion numerous lawsuits that will take years to resolve. A significant amount of the liability and penalties arising from the Gulf oil spill will turn on the treatment given to the terms "gross negligence" and "willful misconduct." Should the United States decide to bring a criminal complaint for manslaughter for the lives lost in the accident, "gross negligence" may also be an element in defining the crime. The terms involve interpretation as statutory, contractual, and common law standards. The undertaking is more complex than it might first appear; it will involve courts, arbitrators, and federal agencies. Because of the complexity, some framework for interpretation of the terms may be useful. -

Duties of Care Under the Revised Uniform Partnership Act Gerardc

Duties of Care Under the Revised Uniform Partnership Act GerardC. Martint Since 1914, the Uniform Partnership Act ( tUPA7) 1 has pro- vided background principles to resolve disputes between partners who lack an explicit partnership agreement.2 However this Act was revised in 1994, resulting in several fundamental altera- tions. Among other changes, this Revised Uniform Partnership Act ("RUPA7) added an explicit duty of care of partners to each other and the partnership.4 Whereas the UPA was silent on such a duty, implicitly deferring both to the common law of agency and to a specialized partnership case law derived therefrom,5 the RUPA seeks explicitly to provide an exclusive delineation of partners' fiduciary duties to the partnership and to each other.' This Comment discusses the RUPA's duty of care provision and seeks to determine when and how the Act's "gross negli- gence" duty of care standard7 should be applied. Specifically, the Comment focuses on three questions: (1) Does the RUPA's "gross negligence" standard replace the common law's agency-based f B.A. 1993, Yale University;, J.D. 1998, The University of Chicago. ' Uniform Partnership Act (1914), 6 Uniform Laws Annotated ("UIA") 125 (West 1995). 2 Until recently, the UPA was law in every state except Louisiana. Allan W. Vestal, Choice of Law and the FiduciaryDuties of Partners Under the Revised Uniform Partner- ship Act, 79 Iowa L Rev 219, 221 n 12 (1994). As enacted, the UPA varied little between states, and remained unchanged in its original form for over seventy-five years. Id. ' Uniform Partnership Act (1994), 6 ULA 1 (West 1995). -

IN the UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT for the DISTRICT of NEBRASKA E3 BIOFUELS-MEAD, LLC, Plaintiff(S), V. SKINNER TANK COMPANY;

8:06-cv-00706-JFB-FG3 Doc # 232 Filed: 01/30/14 Page 1 of 11 - Page ID # <pageID> IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF NEBRASKA E3 BIOFUELS-MEAD, LLC, Plaintiff(s), 8:06CV706 v. SKINNER TANK COMPANY; MEMORANDUM AND ORDER Defendant/Third-Party Plaintiff, v. DILLING MECHANICAL CONTRACTORS, INC. Third-Party Defendant. This matter is before the court on a motion for partial summary judgment filed by defendant/third-party plaintiff Skinner Tank Company (“Skinner”), Filing No. 162. This is an action for breach of contract, fraud, and gross negligence in connection with an ethanol plant construction project in Mead, Nebraska.1 The plaintiffs, E Biofuels-Mead, LLC and E3 Biofuels-Mead, LLC (hereinafter, collectively, “E3”), entered into a contract with defendant Skinner for the purchase, design, fabrication, construction and installation of several tanks to be used in an Integrated Solid Waste and Bio-Fuels Facility (the “Project”) that retrieves usable energy from cattle waste. Jurisdiction is premised on 28 U.S.C. § 1332, diversity of citizenship. 1 The action also involves a counterclaim against E3 and third-party claim against Dilling Construction, the management firm hired by E3 for the project, for tortious interference with a contract, negligence, indemnification and contribution. 8:06-cv-00706-JFB-FG3 Doc # 232 Filed: 01/30/14 Page 2 of 11 - Page ID # <pageID> Skinner moves for a summary judgment of dismissal on the plaintiff’s claims of fraud and gross negligence, asserting that those claims are barred under the economic loss doctrine. Further, it argues that E3 has failed to plead fraud with particularity under Fed. -

“Gross Negligence” Or “Willful Misconduct.” O Put Another Way: Analysis of Preponderance of Evidence Clearly Documents Facts to Support Requirements of § 63.2-1511

COMMONWEALTH OF VIRGINIA Commission on Youth Review of the Standard of Proof to Determine a Founded Case of Child Abuse and Neglect September 18, 2018 Will Egen Study mandate In August 2017, Senator Favola requested that Commission on Youth staff work with the Department of Social Services and Department of Education to update the Commission in reference to an investigative report by NBC4 Washington about a teacher sexual misconduct case. At the September 2017 Commission on Youth meeting, the Commission heard a presentation from the Department of Social Services and the Department of Education on the child protective services (CPS) appeals process and teacher license review process. Commission on Youth staff worked with the Department of Social Services and the Department of Education to craft draft recommendations to be presented at the November 2017 Commission on Youth meeting. The Commission received written and oral public comment on these recommendations. 2 Study mandate At the December 2017 meeting, the Commission adopted a number of recommendations to be presented before the 2018 General Assembly. o Report cases to the Superintendent of Public Instruction when founded. o Report founded cases to the local school board for former school employees. o Shorten the administrative appeals process. The Commission also determined that further study was needed to review the standard of proof for a non-school personnel child protective services investigation vs. a conduct investigation involving a public school employee. The Commission adopted the following recommendation: o Request the Virginia Commission on Youth to study the difference in standards of proof to determine a founded case of child abuse and neglect between school personnel and non-school personnel and to advise the Commission of its findings and recommendations by December 1, 2018. -

A Survey of Typical Claims and Key Defenses Asserted in Recent Hydraulic Fracturing Litigation

Texas A&M Law Review Volume 1 Issue 2 2013 A Survey of Typical Claims and Key Defenses Asserted in Recent Hydraulic Fracturing Litigation Michael Goldman Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.tamu.edu/lawreview Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Michael Goldman, A Survey of Typical Claims and Key Defenses Asserted in Recent Hydraulic Fracturing Litigation, 1 Tex. A&M L. Rev. 305 (2013). Available at: https://doi.org/10.37419/LR.V1.I2.2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Texas A&M Law Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Texas A&M Law Review by an authorized editor of Texas A&M Law Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A SURVEY OF TYPICAL CLAIMS AND KEY DEFENSES ASSERTED IN RECENT HYDRAULIC FRACTURING LITIGATION By: Michael Goldman1 I. INTRODUCTION .......................................... 306 II. TYPICAL CLAIMS ........................................ 308 A. Groundwater ........................................ 308 B. Air .................................................. 309 III. TYPICAL CAUSES OF ACTION ........................... 310 A. Nuisance ............................................ 310 1. Private .......................................... 310 2. Public ........................................... 312 B. Trespass ............................................ 312 C. Negligence and Negligence Per Se ................... 315 D. Breach of Contract .................................. 317 E. Strict Liability ...................................... -

Willful and Wanton, Res Ipsa, Informed Consent

WILLFUL AND WANTON, RES IPSA AND INFORMED CONSENT Bill Liebbe LAW OFFICE OF BILL LIEBBE, P.C. TYLER 223 South Bonner Avenue Tyler, Texas 75702 903-595-1240 telephone 903-595-1325 telecopier DALLAS 3811 Turtle Creek Boulevard Suite 1400 Dallas, Texas 75219 214-321-6100 [email protected] State Bar of Texas 17TH ANNUAL ADVANCED MEDICAL MALPRACTICE COURSE March 18-19, 2010 San Antonio WILLFUL AND WANTON, RES IPSA AND By choosing the words “standard of proof” INFORMED CONSENT rather than “standard of care,” the legislature intended, as it stated in Section 74.153, that a I. WILLFUL AND WANTON claimant “may prove” a departure from the standard of care in providing emergency medical Failure to opine that defendant acted care only if the plaintiff shows that the physician or “willfully and wantonly” in an emergency room healthcare provider “with willful and wanton case does not render the report inadequate. Bosch negligence” deviated from the standard of care. v. Wilbarger Gen. Hosp., 223 S.W.3d 460 (Tex. Thus, the legislature prescribed a claimant’s App.-Amarillo 2006, pet. denied); Benish v. burden of proof at trial in a case involving Grottie 281 S.W.3d 184 (Tex. App.-Fort Worth, emergency medical care. Benish at 193. 2009, pet. denied). Query: Is “willful and wanton negligence” Texas Civil Practice and Remedies Code an affirmative defense or plea in avoidance? Section 74.153 is titled “Standard of Proof in Section 74.151(a) provides that a person who in Cases Involving Emergency Medical Care.” The good faith administers emergency care...is not statutorily created standard of proof and the liable in civil damages for an act performed during applicable medical standards of care are not the the emergency unless the act is willfully and same.