Developing Selectively Nonselective Drugs for Treating CNS Disorders John A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Association Between N-Desmethylclozapine and Clozapine-Induced Sialorrhea

JPET Fast Forward. Published on August 29, 2020 as DOI: 10.1124/jpet.120.000164 This article has not been copyedited and formatted. The final version may differ from this version. 1 Title page Association between N-desmethylclozapine and clozapine-induced sialorrhea: Involvement of increased nocturnal salivary secretion via muscarinic receptors by N- desmethylclozapine Downloaded from Authors and Affiliations: Shuhei Ishikawa, PhD1, 2, a, Masaki Kobayashi, PhD1, 3, *, Naoki Hashimoto, PhD, jpet.aspetjournals.org MD4, Hideaki Mikami, BPharm1, Akihiko Tanimura, PhD5, Katsuya Narumi, PhD1, Ayako Furugen, PhD1, Ichiro Kusumi, PhD, MD4, and Ken Iseki, PhD1 at ASPET Journals on September 23, 2021 1 Laboratory of Clinical Pharmaceutics & Therapeutics, Division of Pharmasciences, Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Hokkaido University 2 Department of Pharmacy, Hokkaido University Hospital 3 Education Research Center for Clinical Pharmacy, Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Hokkaido University 4 Department of Psychiatry, Hokkaido University Graduate School of Medicine 5 Department of Pharmacology, School of Dentistry, Health Sciences University of Hokkaido a Present address: Department of Psychiatry, Hokkaido University Hospital JPET Fast Forward. Published on August 29, 2020 as DOI: 10.1124/jpet.120.000164 This article has not been copyedited and formatted. The final version may differ from this version. 2 Running title page Association between N-desmethylclozapine and CIS Corresponding author: Masaki Kobayashi Downloaded from Laboratory of Clinical Pharmaceutics & Therapeutics, Division of Pharmasciences, Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Hokkaido University, Kita-12-jo, Nishi-6-chome, jpet.aspetjournals.org Kita-ku, Sapporo 060-0812, Japan. Phone/Fax: +81-11-706-3772/3235. E-mail: [email protected] at ASPET Journals on September 23, 2021 Number of text pages: 25 Number of tables: 1 Number of figures: 6 Number of words in the Abstract: 249 Number of words in the Introduction: 686 Number of words in the Discussion: 1492 JPET Fast Forward. -

Rapid and Robust Analysis Method for Quantifying Antidepressants and Major Metabolites in Human Serum by UHPLC-MS/MS

PO-CON1352E Rapid and Robust Analysis Method for Quantifying Antidepressants and Major Metabolites in Human Serum by UHPLC-MS/MS ASMS 2013 WP-095 Vincent Goudriaan1, Christ Pijnenburg2, Jacob Diepenbroek2, Jan Giesbertsen2, Annemieke Vermeulen Windsant-v.d. Tweel2 1Shimadzu Benelux BV, ‘s-Hertogenbosch, Netherlands. 2ZANOB BV, ‘s-Hertogenbosch, Netherlands. Rapid and Robust Analysis Method for Quantifying Antidepressants and Major Metabolites in Human Serum by UHPLC-MS/MS 1. Introduction Therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) of antidepressants is administered drugs, metabolites or endogenic compounds. one of the most widely utilized analysis in clinical labs in UHPLC-MS/MS is much more sensitive, more selective, and Dutch hospitals nowadays. Traditionally quantitation of if robust the perfect replacement of routine HPLC analysis. antidepressants is performed by means of HPLC with Due to simplified sample prep, faster analysis and less diode-array detection (DAD). Obvious disadvantages of the solvent consumption UHPLC-MS/MS is much more cost latter method are: sensitivity, selectivity and possibility of effective. UHPLC-MS/MS methods will replace routine HPLC false positives as a result of co-elution with other methods in clinical labs. 2. Methods and Materials Human serum samples were extracted by means of off-line solid phase extraction. The extracts were analyzed with a Shimadzu Nexera UHPLC combined with a LCMS-8040 Tandem Mass Spectrometer. 5 µL of sample was injected with a SIL-30AC autosampler. 2-1. Sample Preparation Standards both for calibration and control are ready made serum standards. The standards are pretreated in the same way as the samples. 1. Precondition SPE material1 with 1 mL 3% ammonia in acetonitrile 2. -

Screening of 300 Drugs in Blood Utilizing Second Generation

Forensic Screening of 300 Drugs in Blood Utilizing Exactive Plus High-Resolution Accurate Mass Spectrometer and ExactFinder Software Kristine Van Natta, Marta Kozak, Xiang He Forensic Toxicology use Only Drugs analyzed Compound Compound Compound Atazanavir Efavirenz Pyrilamine Chlorpropamide Haloperidol Tolbutamide 1-(3-Chlorophenyl)piperazine Des(2-hydroxyethyl)opipramol Pentazocine Atenolol EMDP Quinidine Chlorprothixene Hydrocodone Tramadol 10-hydroxycarbazepine Desalkylflurazepam Perimetazine Atropine Ephedrine Quinine Cilazapril Hydromorphone Trazodone 5-(p-Methylphenyl)-5-phenylhydantoin Desipramine Phenacetin Benperidol Escitalopram Quinupramine Cinchonine Hydroquinine Triazolam 6-Acetylcodeine Desmethylcitalopram Phenazone Benzoylecgonine Esmolol Ranitidine Cinnarizine Hydroxychloroquine Trifluoperazine Bepridil Estazolam Reserpine 6-Monoacetylmorphine Desmethylcitalopram Phencyclidine Cisapride HydroxyItraconazole Trifluperidol Betaxolol Ethyl Loflazepate Risperidone 7(2,3dihydroxypropyl)Theophylline Desmethylclozapine Phenylbutazone Clenbuterol Hydroxyzine Triflupromazine Bezafibrate Ethylamphetamine Ritonavir 7-Aminoclonazepam Desmethyldoxepin Pholcodine Clobazam Ibogaine Trihexyphenidyl Biperiden Etifoxine Ropivacaine 7-Aminoflunitrazepam Desmethylmirtazapine Pimozide Clofibrate Imatinib Trimeprazine Bisoprolol Etodolac Rufinamide 9-hydroxy-risperidone Desmethylnefopam Pindolol Clomethiazole Imipramine Trimetazidine Bromazepam Felbamate Secobarbital Clomipramine Indalpine Trimethoprim Acepromazine Desmethyltramadol Pipamperone -

LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY Question on Notice

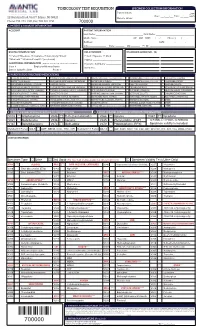

LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY Question On Notice Thursday, 15 February 2018 2560. Ms M. M Quirk to the Minister for Police; I refer to the commencement of operation of the Road Traffic Amendment Act 2016 in March 2017 which introduced compulsory blood or urine samples to be taken from drivers involved in serious crashes, and I ask: (a) since March 2017 how many such samples have been taken; (b) for what specific substances are those blood or urine samples tested; (c) what are the results of those tests to date; and (d) what percentage of drivers have been found to have ingested more than one substance capable of impairing driving skills? Answer (a) The compulsory taking of blood from all drivers involved in serious crashes commenced on 10 March 2017. Between 10 March 2017 and 22 February 2018 (inclusive) a total of 398 blood test samples have been collected under the provision of the Road Traffic Amendment Act 2016. There have been no urine tests collected. (b) Please see attached table for a list of substances in blood sample that are identifiable in ChemCentre toxicology analysis (Paper Number). (c) Of the 398 blood samples collected, 48 are pending results of ChemCentre analysis. Of the 350 analysed, 259 samples had a specific substance(s) detected and 91 samples had no specific substance detected. d) Of the 259 samples with specific substance(s) detected, 92% were found to have multiple substances (more than one). Detectable Substances in Blood Samples capable of identification by the ChemCentre WA. ACETALDEHYDE AMITRIPTYLINE/NORTRIPTYLINE -

Concentrations of Antidepressants, Antipsychotics, and Benzodiazepines in Hair Samples from Postmortem Cases

SN Comprehensive Clinical Medicine (2020) 2:284–300 https://doi.org/10.1007/s42399-020-00235-x MEDICINE Concentrations of Antidepressants, Antipsychotics, and Benzodiazepines in Hair Samples from Postmortem Cases Maximilian Methling1,2 & Franziska Krumbiegel1 & Ayesha Alameri1 & Sven Hartwig1 & Maria K. Parr2 & Michael Tsokos1 Accepted: 30 January 2020 /Published online: 10 February 2020 # The Author(s) 2020 Abstract Certain postmortem case constellations require intensive investigation of the pattern of drug use over a long period before death. Hair analysis of illicit drugs has been investigated intensively over past decades, but there is a lack of comprehensive data on hair concentrations for antidepressants, antipsychotics, and benzodiazepines. This study aimed to obtain data for these substances. A LC-MS/MS method was developed and validated for detection of 52 antidepressants, antipsychotics, benzodiazepines, and metabolites in hair. Hair samples from 442 postmortem cases at the Institute of Legal Medicine of the Charité-University Medicine Berlin were analyzed. Postmortem hair concentrations of 49 analytes were obtained in 420 of the cases. Hair sample segmentation was possible in 258 cases, and the segments were compared to see if the concentrations decreased or increased. Descriptive statistical data are presented for the segmented and non-segmented cases combined (n = 420) and only the segmented cases (n = 258). An overview of published data for the target substances in hair is given. Metabolite/parent drug ratios were investigated for 10 metabolite/parent drug pairs. Cases were identified that had positive findings in hair, blood, urine, and organ tissue. The comprehensive data on postmortem hair concentrations for antidepressants, antipsychotics, and benzodiazepines may help other investigators in their casework. -

Drug–Drug Interactions Involving Intestinal and Hepatic CYP1A Enzymes

pharmaceutics Review Drug–Drug Interactions Involving Intestinal and Hepatic CYP1A Enzymes Florian Klomp 1, Christoph Wenzel 2 , Marek Drozdzik 3 and Stefan Oswald 1,* 1 Institute of Pharmacology and Toxicology, Rostock University Medical Center, 18057 Rostock, Germany; fl[email protected] 2 Department of Pharmacology, Center of Drug Absorption and Transport, University Medicine Greifswald, 17487 Greifswald, Germany; [email protected] 3 Department of Experimental and Clinical Pharmacology, Pomeranian Medical University, 70-111 Szczecin, Poland; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +49-381-494-5894 Received: 9 November 2020; Accepted: 8 December 2020; Published: 11 December 2020 Abstract: Cytochrome P450 (CYP) 1A enzymes are considerably expressed in the human intestine and liver and involved in the biotransformation of about 10% of marketed drugs. Despite this doubtless clinical relevance, CYP1A1 and CYP1A2 are still somewhat underestimated in terms of unwanted side effects and drug–drug interactions of their respective substrates. In contrast to this, many frequently prescribed drugs that are subjected to extensive CYP1A-mediated metabolism show a narrow therapeutic index and serious adverse drug reactions. Consequently, those drugs are vulnerable to any kind of inhibition or induction in the expression and function of CYP1A. However, available in vitro data are not necessarily predictive for the occurrence of clinically relevant drug–drug interactions. Thus, this review aims to provide an up-to-date summary on the expression, regulation, function, and drug–drug interactions of CYP1A enzymes in humans. Keywords: cytochrome P450; CYP1A1; CYP1A2; drug–drug interaction; expression; metabolism; regulation 1. Introduction The oral bioavailability of many drugs is determined by first-pass metabolism taking place in human gut and liver. -

Toxicology Test Requisition Specimen Collection/Information

TOXICOLOGY TEST REQUISITION SPECIMEN COLLECTION/INFORMATION Patient Initials: ________________ ☐am 22 Meridian Road, Unit 7, Edison, NJ 08820 Date: ___/___/___ Time: __:____ ☐pm Labelc Donor’s Initials: ________________ Phone: 732-474-1120, Fax: 732-321-1150 700000 1. PATIENT & ACCOUNT INFORMATION ACCOUNT PATIENT INFORMATION Last Name: _____________________________________ First Name: ______________________________ Middle Name: __________________________ ☐F ☐M DOB: ___/___/___ Phone: (____)____ - ____ Address: __________________________________________________ SSN: _______ - ______ - ______ City:______________ State: _______ Zip:_______ Pt. ID: ___________________________________ BILLING INFORMATION RELATIONSHIP DIAGNOSIS CODES (ICD - 10) ☐ Patient ☐Medicare ☐ Insurance ☐ Auto Injury ☐Client ☐ Self ☐Spouse ☐ Child ☐Medicaid ☐ Workers Comp/PIP (see below) ☐Other _________________________ ADDITIONAL INFORMATION (Required for all Workers Comp or if no insurance card is attached) Insurance Company: ____________ Case # _____________ Employer/Attorney Name: _______________ Member # _____________________ Date of Injury/Accident: _______________ Phone # ______________ 2. PARENT DRUG (PRESCRIBED MEDICATIONS) ALPRAZOLAM (XANAX) CYCLOBENZAPRINE (AMRIX, FEXMID, FLEXTRIL) LORAZEPAM (ATIVAN, LORAZAPAM INTENSOL) OXYMORPHONE (OPANA IR, NUMORPHAN) VENLAFAXINE (EFFEXOR) AMITRIPTYLINE (ELAVIL) DESIPRAMINE (NORPRAMINE, PERTOFRANE) MAPROTILINE (LUDIOMIL) PHENOBARBITAL (LUMINAL, SOLFOTON) VILAZODONE (VIIBRYD) AMPHETAMINE (ADDERALL, VYVANSE) DIAZEPAM -

Specimen Collection & Transport Guide

2018-2019 Specimen Collection & Transport Guide Visit our online version at QuestDiagnostics.com/TestDirectory Return to Table of Contents DirectorySpecimen of Collection Services & Transport Guide 2018-2019 QuestDiagnostics.com The CPT® codes provided in this document are based on AMA guidelines and are for informational purposes only. CPT® coding is the sole responsibility of the billing party. Please direct any questions regarding coding to the payer being billed. Quest, Quest Diagnostics, any associated logos, and all associated Quest Diagnostics registered and unregistered trademarks are the property of Quest Diagnostics. All third party marks—® and ™—are the property of their respective owners. © 2018 Quest Diagnostics Incorporated. All rights reserved. Table of Contents Directory of Services 5 Bacterial Identification (Aerobic) and Susceptibility Bacterial Idntifcaiton (Aerobic) Only Where to Find Information ................................................................7 Susceptibility Panel, Aerobic Bacterium About Us: The World’s Leading Laboratory .....................................7 Fungal Isolate Identification Test Additions After Submission of Specimen ..................................7 Mycobacterium Identification ..........................................................48 Reporting ..........................................................................................7 Bacterial Vaginosis & Vaginitis .......................................................48 Confidentiality ...................................................................................8 -

A New Possible Class of Drugs for the Treatment of Schizophrenia

Clinical News Robert R. Conley, MD Editor-in-Chief A New Possible Class of Drugs for the as a treatment for schizophrenia. However, understanding Treatment of Schizophrenia how to affect the many different kinds of glutamate receptors A clinical trial in the September issue of Nature in medically beneficial ways has proved complicated and has Medicine describes a drug, LY2140023, which may be ef- not lead to any beneficial therapies. So, instead of focusing fective in people with schizophrenia psychosis. This drug on the receptors blocked by PCP and ketamine, Dr. Schoepp is thought to work by targeting glutamate-mediated neuro- and colleagues concentrated on modulating the action of transmission. Previously, glutamate neurotransmission has glutamate receptors in the brain’s prefrontal cortex, an area been touted as an important factor in schizophrenia, but responsible for personality and learning. Dr. Schoepp left clinical evidence of efficacy has been lacking. All current an- Lilly in March to become the head of neuroscience research tipsychotic drugs target dopamine receptors. It is this mode for Merck. However, it has been reported that Dr. Schoepp of action that is thought to be responsible for extrapyrami- and Dr. Steven Paul, the president of Lilly Research Labora- dal side effects, including tardive dyskinesia and dysphoria, tories, have both said that his departure would not hurt the which cause many patients to frequently discontinue their development of LY2140023. medication. LY2140023 is a selective agonist of a specific Because this was a “proof-of-concept” study designed to subtype of glutamate receptor, known as mGlu2/3. It is re- test the efficacy of LY2140023 in the treatment of schizophre- ported that Lilly Research Laboratories will begin a larger nia, no rigorous comparison was made against olanzapine in clinical trial for the drug immediately. -

N-Desmethylclozapine, an Allosteric Agonist at Muscarinic 1 Receptor, Potentiates N-Methyl- D-Aspartate Receptor Activity

N-desmethylclozapine, an allosteric agonist at muscarinic 1 receptor, potentiates N-methyl- D-aspartate receptor activity Cyrille Sur*†, Pierre J. Mallorga*, Marion Wittmann*, Marlene A. Jacobson*, Danette Pascarella*, Jacinta B. Williams*, Philip E. Brandish‡, Douglas J. Pettibone*, Edward M. Scolnick‡, and P. Jeffrey Conn*§ Departments of *Neuroscience and ‡Neurobiology, Merck & Co. Inc., West Point, PA 19486 Contributed by Edward M. Scolnick, September 2, 2003 The molecular and neuronal substrates conferring on clozapine its effects of clozapine, its partial muscarinic agonist activities may unique and superior efficacy in the treatment of schizophrenia contribute to its unique therapeutic profile. Notably, antimus- remain elusive. The interaction of clozapine with many G protein- carinics have been reported to induce psychosis, confusion, and coupled receptors is well documented but less is known about its cognitive deficits in humans (16, 17), and double-blind, placebo- biologically active metabolite, N-desmethylclozapine. Recent clin- controlled clinical study with M1͞M4 agonist xanomeline in ical and preclinical evidences of the antipsychotic activity of the Alzheimer’s disease patients revealed significant improvements muscarinic agonist xanomeline prompted us to investigate the in psychotic behavior and cognitive abilities (18) in agreement effects of N-desmethylclozapine on cloned human M1–M5 musca- with preclinical studies supporting xanomeline’s antipsychotic rinic receptors. N-desmethylclozapine preferentially bound to M1 profile (19, 20). Interestingly, these effects of xanomeline are muscarinic receptors with an IC50 of 55 nM and was a more potent consistent with the reported potentiation of N-methyl-D- partial agonist (EC50, 115 nM and 50% of acetylcholine response) aspartate (NMDA) receptor activity by muscarinic agonist in rat at this receptor than clozapine. -

Clozapine Plasma Levels

Clozapine Plasma Levels Clozapine plasma levels may be helpful in improving response rates and minimizing unnecessary side effects. Key facts about plasma levels: • Inter-individual variation in blood level is high at constant dose (8-20 fold variation) • Intra-individual variation in blood level is low on a clozapine constant dose (<20 percent) • Clozapine is metabolized by the liver and therefore is exposed to drug interactions • Clozapine side effects are often concentration/dose dependent • Serum concentrations are age and gender dependent Clozapine Plasma Level Monitoring is recommended under the Following Conditions: • Any patient receiving more than 600 mg/day, given the increased risk of seizure above this dosage • When there is a question about compliance • Patients showing excessive side effects at normal doses who may be metabolizing clozapine less efficiently – e.g. the elderly • When monitoring for drug-drug interaction(s) that alter clozapine metabolism Clozapine plasma levels can also be used to examine response-dose patterns: • The range of clozapine plasma levels associated with clinically meaningful response appears to be wide, ranging from 200 ng/mL to 450 ng/mL. • Some studies indicate a range of plasma levels between 350 ng/mL and 450 ng/mL associated with clinically meaningful response, but many patients respond to lower plasma levels of clozapine. • Clinicians should use clinical judgment with plasma level data to find the best response while minimizing side effects. • The target plasma level for the vast majority of patients may be approximately 350 ng/mL. Higher plasma levels may result in greater sedation and other unwanted side effects. • However, patients who have not responded at a plasma level of 350 ng/mL after 6 weeks of treatment should be raised to above 450 ng/mL. -

Screening of 300 Drugs in Blood Utilizing Second Generation

Screening of 300 Drugs in Blood Utilizing Second Generation Exactive Plus High-Resolution, Accurate Mass Spectrometer and ExactFinder Software Kristine Van Natta, Marta Kozak, Xiang He Thermo Fisher Scientific, San Jose, CA FIGURE 2. Schematic diagram of the Exactive Plus high-resolution accurate FIGURE 5. ExactFinder processing method and database. FIGURE 7. LODs for around 490 compounds For targeted screening, ExactFinder uses parameters set in processing method to Overview mass benchtop mass spectrometer. identify and confirm the presence of compound based on database values. Figure 8 Purpose: Evaluate Thermo Scientific Exactive Plus high performance bench-top mass Compound LOD Compound LOD Compound LOD Compound LOD shows data review results for one donor sample. In this method, compounds were 1‐(3‐Chlorophenyl)piperazine 5 Deacetyl Diltiazem 5 Lormetazepam 5 Perimetazine 5 identified by accurate mass within 5 ppm and retention time. Identity was further spectrometer for drug screening of whole blood for forensic toxicology purposes. 10‐hydroxycarbazepine 5 Demexiptiline 5 Loxapine 5 Phenacetin 5 5‐(p‐Methylphenyl)‐5‐phenylhydantoin 10 Des(2‐hydroxyethyl)opipramol 5 LSD 5 Phenazone 5 confirmed by isotopic pattern and presence of known fragments. Methods: Whole blood samples were processed by precipitation with ZnSO / 6‐Acetylcodeine 100 Desalkylflurazepam 5 Maprotiline 5 Pheniramine 5 4 6‐Methylthiopurine 5 Desipramine 5 Maraviroc 5 Phenobarbital 5 Matrix effects were observed to be compound dependent and were generally within methanol. Samples were injected onto an HPLC under gradient conditions and 6‐Monoacetylmorphine 5 Desmethylcitalopram 5 MBDB 5 Phenylbutazone 5 7(2,3dihydroxypropyl)Theophylline 5 Desmethylclozapine 50 MDEA 5 Phenytoin 10 ±50%.