Send in the Clowns Shakespeare on the Soviet Screen by Ronan Paterson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conscious Responsibility 2 Contents

Social Report 2016 World Without Barriers. VTB Group Conscious Responsibility 2 Contents VTB Group in 2016 4 3.3. Internal communications and corporate culture 50 Abbreviations 6 3.4. Occupational health and safety 53 Statement of the President and Chairman of the Management Board of VTB Bank (PJSC) 8 4. Social environment 56 1. About VTB Group 10 4.1. Development of the business environment 57 1.1. Group development strategy 12 4.2. Support for sports 63 1.2. CSR management 13 4.3. Support for culture and the arts 65 1.3. Internal (compliance) control 16 4.4. Support for health care and education 69 1.4. Stakeholder engagement 17 4.5. Support for vulnerable social groups 71 2. Market environment 26 5. Natural environment 74 2.1. Support for the public sector and socially significant business 27 5.1. Sustainable business practices 74 2.2. Support for SMBs 34 5.2. Financial support for environmental projects 77 2.3. Quality and access to banking services 35 6. About the Report 80 2.4. Socially significant retail services 38 7. Appendices 84 3. Internal environment 44 7.1. Membership in business associations 84 3.1. Employee training and development 46 7.2 GRI content index 86 3.2. Employee motivation and remuneration 49 7.3. Independent Assurance Report 90 VTB Social Report 2016 About VTB Group Market environment Internal environment Social environment Natural environment About the Report Appendices VTB Group in 2016 4 VTB Group in 2016 5 RUB 51.6 billion earned 72.7 thousand people 274.9 thousand MWh in net profit employed by the Group -

Yuri Lyubimov: Thirty Years at the Taganka Theatre

YURY LYUBIMOV Contemporary Theatre Studies A series of books edited by Franc Chamberlain, Nene College, Northampton, UK Volume 1 Playing the Market: Ten Years of the Market Theatre, Johannesburg, 1976–1986 Anne Fuchs Volume 2 Theandric: Julian Beck’s Last Notebooks Edited by Erica Bilder, with notes by Judith Malina Volume 3 Luigi Pirandello in the Theatre: A Documentary Record Edited by Susan Bassnett and Jennifer Lorch Volume 4 Who Calls the Shots on the New York Stages? Kalina Stefanova-Peteva Volume 5 Edward Bond Letters: Volume I Selected and edited by Ian Stuart Volume 6 Adolphe Appia: Artist and Visionary of the Modern Theatre Richard C.Beacham Volume 7 James Joyce and the Israelites and Dialogues in Exile Seamus Finnegan Volume 8 It’s All Blarney. Four Plays: Wild Grass, Mary Maginn, It’s All Blarney, Comrade Brennan Seamus Finnegan Volume 9 Prince Tandi of Cumba or The New Menoza, by J.M.R.Lenz Translated and edited by David Hill and Michael Butler, and a stage adaptation by Theresa Heskins Volume 10 The Plays of Ernst Toller: A Revaluation Cecil Davies Please see the back of this book for other titles in the Contemporary Theatre Studies series YURY LYUBIMOV AT THE TAGANKA THEATRE 1964–1994 Birgit Beumers University of Bristol, UK harwood academic publishers Australia • Canada • China • France • Germany • India Japan • Luxembourg • Malaysia • The Netherlands • Russia Singapore • Switzerland • Thailand • United Kingdom Copyright © 1997 OPA (Overseas Publishers Association) Amsterdam B.V. Published in The Netherlands by Harwood Academic Publishers. This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005. -

The Theatre of Death: the Uncanny in Mimesis Tadeusz Kantor, Aby Warburg, and an Iconography of the Actor; Or, Must One Die to Be Dead?

The Theatre of Death: The Uncanny in Mimesis Tadeusz Kantor, Aby Warburg, and an Iconography of the Actor; Or, must one die to be dead? Mischa Twitchin Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. 1 The Theatre of Death: the Uncanny in Mimesis (Abstract) The aim of this thesis is to explore an heuristic analogy as proposed in its very title: how does a concept of the “uncanny in mimesis” and of the “theatre of death” give content to each other – historically and theoretically – as distinct from the one providing either a description of, or even a metaphor for, the other? Thus, while the title for this concept of theatre derives from an eponymous manifesto of Tadeusz Kantor’s, the thesis does not aim to explain what the concept might mean in this historically specific instance only. Rather, it aims to develop a comparative analysis, through the question of mimesis, allowing for different theatre artists to be related within what will be proposed as a “minor” tradition of modernist art theatre (that “of death”). This comparative enquiry – into theatre practices conceived of in terms of the relation between abstraction and empathy, in which the “model” for the actor is seen in mannequins, puppets, or effigies – is developed through such questions as the following: What difference does it make to the concept of “theatre” when thought of in terms “of death”? What thought of mimesis do the dead admit of? How has this been figured, historically, in aesthetics? How does an art of theatre participate -

Of Morbid Jealousy in Orson Welles's Noir Othello (1952)

Scripta Uniandrade, v. 14, n. 2 (2016) Revista da Pós-Graduação em Letras – UNIANDRADE Curitiba, Paraná, Brasil “OCULAR PROOF” OF MORBID JEALOUSY IN ORSON WELLES'S NOIR OTHELLO (1952) Dr. ALEXANDER MARTIN GROSS Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina (UFSC) Florianópolis, Santa Catarina, Brasil ([email protected]) ABSTRACT: This article considers Orson Welles's Othello (1952) as a performance text in its own right, and discusses the film's use of cinematographic techniques in constructing a visual language which complements the verbal language of Shakespeare's playtext. The 1965 National Theatre filmed production of Othello (dir. Stuart Burge) is also discussed in order to further highlight the cinematic qualities of the Welles production. Particular attention is paid to Welles's use of cinematographic techniques and black and white photography to foreground themes of enclosure, entrapment, and opposition in his visual interpretation of the playtext. The film is considered as an example of visual rewrighting, using Alan Dessen's term which applies to situations where a director moves closer to the role of a playwright. KEYWORDS: Shakespeare on film. Othello. Performance. Artigo recebido: 23 set. 2016. Aceito: 03 nov. 2016. GROSS, Alexander Martin. "Ocular Proof" of Morbid Jealousy in Orson Welles's Noir Othello (1952). Scripta Uniandrade, v. 14, n. 2 (2016), p. 43-56. Curitiba, Paraná, Brasil Data de edição: 27 dez. 2016. 43 Scripta Uniandrade, v. 14, n. 2 (2016) Revista da Pós-Graduação em Letras – UNIANDRADE Curitiba, Paraná, Brasil “PROVA OCULAR” DA INVEJA MÓRBIDA EM OTELO DE ORSON WELLES (1952) RESUMO: O presente artigo considera o filme Otelo de Orson Welles (1952) como um performance text de mérito próprio, e examina o uso de técnicas cinematográficas na construção de uma linguagem visual que complementa a linguagem verbal do texto de Shakespeare. -

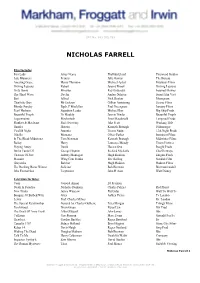

Nicholas Farrell

VAT No. 993 055 789 NICHOLAS FARRELL Film Includes: Iron Lady Airey Neave Phyllida Lloyd Pinewood Studios Late Bloomers Francis Julie Gavras The Bureau Amazing Grace Henry Thornton Michael Apted Fourboys Films Driving Lessons Robert Jeremy Brook Driving Lessons Dirty Bomb Minister Roy Battersby Inspired Movies The Third Wave Devlin Anders Nilsson Sonet Film Vast Bait Alfred Nick Renton Monogram Charlotte Grey Mr Jackson Gillian Armstrong Ecosse Films Bloody Sunday Bgdr. P Maclellan Paul Greengrass January Films Pearl Harbour Squadron Leader Michael Bay Big Ship Prods Beautiful People Dr Mouldy Jasmin Dixdar Beautiful People Legionnaires Mackintosh Peter Macdonald Longroad Prods Plunkett & Macleane Pm's Secretary Jake Scott Working Title Hamlet Horatio Kenneth Branagh Fishmonger Twelfth Night Antonio Trevor Nunn 12th Night Prods Othello Montano Oliver Parker Imminent Films In The Bleak Midwinter Tom Newman Kenneth Branagh Midwinter Films Bailey Harry Laurence Moody Union Pictures Playing Away Derek Horace Ove Insight Prods. Berlin Tunnel 21 George Heptner Richard Michaels Cbs/filmways Chariots Of Fire Aubrey Montague Hugh Hudson Enigma Prods Matador Wing Com Franks Eric Balling Nordisk Film Greystoke Belcher Hugh Hudson Hudson Films The Rocking Horse Winner Solicitor Bob Bierman Bierman/randall Lthe Eternal Sea Lieytenant John H Auer Walt Disney Television Includes: Coup General Anson Ed Fraiman Death In Paradise Nicholas Dunham Charlie Palmer Red Planet New Tricks James Winslow Phil John Wall To Wall Tv Bouquet Of Barbed Wire Giles Ashley -

Boxoffice Barometer (April 15, 1963)

as Mike Kin*, Sherman. p- builder the empire Charlie Gant. General Rawlmgs. desperadc as Linus border Piescolt. mar the as Lilith mountain bub the tut jamblei's Zeb Rawlings, Valen. ;tive Van horse soldier Prescott, e Zebulon the tinhorn Rawlings. buster Julie the sod Stuart, matsbil's*'' Ramsey, as Lou o hunter t Pt«scott. marsl the trontie* tatm gal present vjssiuniw SiNGiN^SVnMNG' METRO GOlPWVM in MED MAYER RICHMOND Production BLONDE? BRUNETTE? REDHEAD? Courtship Eddies Father shih ford SffisStegas 1 Dyke -^ ^ panairtSioo MuANlNJR0( AMAN JACOBS , st Grea»e Ae,w entl Ewer Ljv 8ecom, tle G,-eai PRESENTS future as ^'***ied i Riel cher r'stian as Captain 3r*l»s, with FILMED bronislau in u, PANAVISION A R o^mic RouND WofBL MORE HITS COMING FROM M-G-M PmNHunri "INTERNATIONAL HOTEL (Color) ELIZABETH TAYLOR, RICHARD BURTON, LOUIS JOURDAN, ORSON WELLES, ELSA MARTINELLI, MARGARET RUTHERFORD, ROD TAYLOR, wants a ROBERT COOTE, MAGGIE SMITH. Directed by Anthony Asquith. fnanwitH rnortey , Produced by Anotole de Grunwald. ® ( Pana vision and Color fEAlELI Me IN THE COOL OF THE DAY” ) ^sses JANE FONDA, PETER FINCH, ANGELA LANSBURY, ARTHUR HILL. Mc^f^itH the Directed by Robert Stevens. Produced by John Houseman. THE MAIN ATTRACTION” (Metrocolor) PAT BOONE and NANCY KWAN. Directed by Daniel Petrie. Produced LPS**,MINDI// by John Patrick. A Seven Arts Production. CATTLE KING” [Eastmancolor) ROBERT TAYLOR, JOAN CAULFIELD, ROBERT LOGGIA, ROBERT MIDDLETON, LARRY GATES. Directed by Toy Garnett. Produced by Nat Holt. CAPTAIN SINDBAD” ( Technicolor— WondroScope) GUY WILLIAMS, HEIDI BRUEHL, PEDRO ARMENDARIZ, ABRAHAM SOFAER. Directed by Byron Haskin. A Kings Brothers Production. -

Programme Is Being Presented in Russia Tuesday, 12Th April Friday, 15Th April Saturday, 16Th April

In 2011, this is the first time the Europe Theatre Prize programme is being presented in Russia Tuesday, 12th April Friday, 15th April Saturday, 16th April 9 a.m. EUROPE PRIZE NEW THEATRICAL REALITIES 9 a.m. EUROPE PRIZE NEW THEATRICAL REALITIES From April 12 to April 17, 2011, St. Petersburg will be a capital of the 2 p.m. Press conference dedicated to opening EUROPE PRIZE NEW THEATRICAL REALITIES RUSSIAN ACCENT/ST. PETERSBURG PERFORMANCES 7.30 p.m. EUROPE THEATRE PRIZE Conference and meeting with Vesturport Theatre Conference and meeting most prestigious theatre event in Europe. of Europe Theatre Prize events 2011 7 p.m. Finnish National Theatre 7.30 p.m. A.S. Pushkin Russian State Academic Drama SPECIAL PRIZE curator: Michael Billington with Teatro Meridional A.S. Pushkin State Academic Russian Drama Mr. Vertigo (Alexandrinsky) Theatre EUROPE PRIZE NEW THEATRICAL REALITIES Born in 1986 and presented in 1987 as a European Commission pilot (Alexandrinsky) Theatre by Paul Auster Big Hall, House of Actors curator: Maria Helena Serôdio Your Gogol project, the Europe Theatre Prize is usually awarded to artists and 6, Ostrovsky Sq. directed by Kristian Smeds (2nd repeat) 86, Nevsky Pr. Big Hall after works of Nikolay Gogol AWARD CEREMONY A.S. Pushkin Russian State Academic Drama theatre institutions which through their work have contributed to (international preview) House of Actors directed by Valery Fokin (Alexandrinsky) Theatre mutual understanding between nations. The European Parliament SPECIAL PRIZE Baltic House Theatre-festival EUROPE PRIZE NEW THEATRICAL REALITIES 86, Nevsky Pr. 6, Ostrovsky Sq. 6, Ostrovsky Sq. and the European Council have placed this Prize among institutions 7 p.m. -

Syllabus MA English Semester 1 Course Title: Literary Criticism-I Course Code

Syllabus M.A. English Semester 1 Course Title: Literary Criticism-I Course Code: SLLCHC001ENG3104 L T P Credits 3 1 0 4 Total Lectures: 60 Objective: –The course intends to provide a critical understanding of the developments in literary criticism from the beginnings to the end of 19th century. Moreover some selected texts/critics are prescribed for detailed study whose contribution to this area constitutes a significant benchmark in each era. It also provides a conceptual framework for developing an understanding of the function and practice of traditional modes of literary criticism. Prescribed Texts: Unit - A Aristotle: Poetics (Chapters i-xvi, xxv) Unit - B William Wordsworth: Preface to Lyrical Ballads Unit - C Matthew Arnold: The Function of Criticism in the Present Time Unit - D T. S. Eliot: Tradition and the Individual Talent Suggested readings: Abrams, M. H. A Glossary of Literary Terms. Singapore: Harcourt Asia Pvt. Ltd., 2000. Arnold, Matthew. Essays in Criticism. New York: MacMillan and company, 1865. Blamires, Harry. A History of Literary Criticism. Delhi: Macmillan, 2001. Daiches, David. Critical Approaches to Literature, 2nd ed. Hyderabad: Orient Longman, 2001. Ford, Boris (ed). The Pelican Guide to English Literature, Vols. 4 & 5. London: Pelican, 1980. Habib, M. A. R. A History of Literary Criticism and Theory: From Plato to the Present. Oxford: Blackwell, 2005. House, Humphrey. Aristotle’s Poetics. Ludhiana: Kalyani Publishers, 1970. Lucas, F. L. Tragedy in Relation to Aristotle’s Poetics. New Delhi: Allied Publishers, 1970. Nagarajan, M.S. English Literary Criticism & Theory: An Introductory History. Hyderabad: Orient Longman, 2006. Waugh, Patricia. Literary Theory & Criticism: An Oxford Guide. -

By Zukhra Kasimova Submitted to Central European University Department of History Supervisor

ILKHOM IN TASHKENT: FROM KOMSOMOL-INSPIRED STUDIO TO POST-SOVIET INDEPENDENT THEATER By Zukhra Kasimova Submitted to Central European University Department of History In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Supervisor: Professor Charles Shaw Second Reader: Professor Marsha Siefert CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2016 Copyright in the text of this thesis rests with the Author. Copies by any process, either in full or part, may be made only in accordance with the instructions given by the Author and lodged in the Central European Library. Details may be obtained from the librarian. This page must form a part of any such copies made. Further copies made in accordance with such instructions may not be made without the written permission of the Author. CEU eTD Collection 1 ABSTRACT This thesis aims to research the creation of Ilkhom as an experimental theatre studio under Komsomol Youth League and Theatre Society in the late Brezhnev era in Tashkent, the capital of Uzbek SSR. The research focuses on the controversies of the aims and objectives of these two patronage organizations, which provided an experimental studio with a greater freedom in choice of repertoire and allowed to obtain the status of one of the first non-government theaters on the territory of former Soviet Union. The research is based on the reevaluation of late- Soviet/early post-Soviet period in Uzbekistan through the repertoire of Ilkhom as an independent theatre-studio. The sources used include articles about theatre from republican and all-union press. CEU eTD Collection 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am grateful to my research advisor, Professor Charles Shaw, for encouraging me to focus on Soviet theatre developments in Central Asia, as well as for his guidance and tremendous support throughout the research process. -

Happy Valentine's Day!

MOSCOW FEBRUARY 2011 www.passportmagazine.ru JURIES, NIGHTCLUBS AND WINE FACTORIES HAPPY VALENTINE’S DAY! KINKI FISH AND SABLE COATS TAGANKA , CHEKHOV MUSEUM AND THE DAY THE WHITE HOUSE TURNED BLACK February_covers.indd 1 21.01.2011 12:18:50 February_covers.indd 2 21.01.2011 12:27:07 Contents 3. Editor’s Choice Alevitina Kalenina, Olga Slobodkina 10. Fashion Fir is a girl’s best friend, Alexandra Vorontsova 12. Travel 10 Kyrgistan, Luc Jones 14. The Way It Was 1993, John Harrison “Oh Thou That Tellest Good Tidings to Moscow,” Helen Womack Shock Troops part II, Art Franczek Beria’s mistress comes out of the closet Helen Womack 14 20 The Way It Is The Juries Out on Juries in Russia: part I, Ian Mitchell 24. Your Moscow Taganka: The Haunts of Intelligentsia and Blue-Collar Grit , Katrina Marie Chekhov’s House and Museum, Marina Kashpar 24 28. Real Estate Real Estate News, Vladimir Kozlev Internet Services at Home, Vladimir Kozlev 32 Wine & Dining Vinodelnya Vedernikoff: genuine Russian wine, Eleonora Scholes Vinzavod, Charles Borden Get Kinki, Charles Borden 32 38. Clubs An Interview with Campbell Bethwaite: Secrets of Moscow’s Nightlife, Miguel Francis 40. Wine & Dining Restaurant Directory 42. My World Dare to ask Dare, Deidre Dare 38 43. Family Pages Puzzle Page, Ross Hunter Pileloop III, Natalie Kurtog 47. Book Review The Forsaken by Tim Tzouliadis, Ian Mitchell 46 48.Distribution list February 2011 3 Letter from the Publisher This year I planned my vacation 1 month in advance and decided to go to Dubai were you can see the sun every day. -

Zuzana Spodniaková Vladimir Vysotsky: a Hamlet with a Guitar

82 Zuzana Spodniaková 83 European Journal of Media, Art & Photography Media / Art / Culture Vladimir Vysotsky: A Hamlet with a Guitar instead of a Sword It has been four hundred Understanding Hamlet means un- of the 1970s. He has inspired and Zuzana Spodniaková and fifteen years since William derstanding the era. (...)3 influenced a number of Hamlet gen- Shakespeare (1564 – 1616), English Hamlet became a witness of his erations to come, even beyond the so playwright and poet, wrote one time in one of the most important borders of the time. Vladimir Vy tsky: A Hamlet with of the world’s most brilliant works productions of the second half of Vysotsky who performed Hamlet of dramatic literature at the turn the 20th century4 of the Moscow two hundred and twenty-one times ns of 1603 –1604, which is among the Theatre of Drama and Comedy in nine seasons, became one with a Guitar i tead of a Sword most staged and most translated on Taganka Square, with Vladimir him and slipped into the character: theatre pieces in Western culture. Vysotsky (1938 – 1980), foremost “Sometimes, it seems that it is not For over four centuries, the story Russian actor, poet, and performer the actor rendering Hamlet, but of the Prince of Denmark has been of his own songs,5 in the lead role. rather the Prince of Denmark is be- shedding light on changes and de- Though loved both as a man and an ing reincarnated in Vysotsky – actor, velopments in the theatre, in the artist by the people, he was banned poet, menestrel.”8 In the history of Abstract approach of its creators -

From 2000 Known As Perth International Arts Festival)

FESTIVAL OF PERTH PROGRAMMES (FROM 2000 KNOWN AS PERTH INTERNATIONAL ARTS FESTIVAL) Date Venue Title & Author Director Producer Principals 1990 Undated Join the Friends of the Order form and Festival. Membership questionnaire form and questionnaire 1990 1990 Festival Program WA Theatre Company Robert Juniper Limited Order form and letter Edition print “Bran Nue Dae” 13-24 Feb 1990 Octagon Theatre Gondwanaland Festival of Perth 1990 Charlie McMahon Country venues Eddie Duquemin Peter Carolan 14 Feb 1990 Hole in the Wall Theatre Wallflowering by Peta Aarne Neeme Bernard Angell Kevan Johnston Murray Jill Perryman 14-24 Feb 1990 His Majesty’s Theatre Josef Nadj Company Festival of Perth 1990 Postcard advertisement Postcard photograph 14 Feb-10 Mar 1990 His Majesty’s Theatre Dance 90 Josef Nadj Gerard Gourdot Quarry Amphitheatre Josef Nadj Company Barry Moreland Laszlo Hudi & Company The Sunken Garden WA Ballet Company Members of the ballet Kerala Kalamandalam Dancers of the Kathakali Dancers company 15-23 Feb 1990 Academy Theatre El Cimarron John Milson Lyndon Terracini The Fugitive Slave baritone Hans Werner Henze’s Nova Ensemble Music theatre 18 Feb-11 Mar 1990 Dolphin Theatre The newspaper of Alan Becher Festival of Perth Jenny McNae Claremont Street by Rosemary Barr Elizabeth Jolley Michael Loney 18 Feb – 11 Mar 1990 Various venues The Myer Festival David Blenkinsop Festival of Perth 18-24 Feb 1990 Octagon Theatre Bride of Fortune by David Kram John Milson Merlyn Quaife Gillian Whitehead & Geoffrey Harris & the Anna Maria Dell’oso performers