SOCIAL ISSUES COMMITTEE 2 1 JUL 7Nnq RECE1VED

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Government Gazette of the STATE of NEW SOUTH WALES Number 168 Friday, 30 December 2005 Published Under Authority by Government Advertising and Information

Government Gazette OF THE STATE OF NEW SOUTH WALES Number 168 Friday, 30 December 2005 Published under authority by Government Advertising and Information Summary of Affairs FREEDOM OF INFORMATION ACT 1989 Section 14 (1) (b) and (3) Part 3 All agencies, subject to the Freedom of Information Act 1989, are required to publish in the Government Gazette, an up-to-date Summary of Affairs. The requirements are specified in section 14 of Part 2 of the Freedom of Information Act. The Summary of Affairs has to contain a list of each of the Agency's policy documents, advice on how the agency's most recent Statement of Affairs may be obtained and contact details for accessing this information. The Summaries have to be published by the end of June and the end of December each year and need to be delivered to Government Advertising and Information two weeks prior to these dates. CONTENTS LOCAL COUNCILS Page Page Page Albury City .................................... 475 Holroyd City Council ..................... 611 Yass Valley Council ....................... 807 Armidale Dumaresq Council ......... 478 Hornsby Shire Council ................... 614 Young Shire Council ...................... 809 Ashfi eld Municipal Council ........... 482 Inverell Shire Council .................... 618 Auburn Council .............................. 484 Junee Shire Council ....................... 620 Ballina Shire Council ..................... 486 Kempsey Shire Council ................. 622 GOVERNMENT DEPARTMENTS Bankstown City Council ................ 489 Kogarah Council -

National Disability Insurance Scheme (Becoming a Participant) Rules 2016

National Disability Insurance Scheme (Becoming a Participant) Rules 2016 made under sections 22, 23, 25, 27 and 209 of the National Disability Insurance Scheme Act 2013 Compilation No. 4 Compilation date: 27 February 2018 Includes amendments up to: National Disability Insurance Scheme (Becoming a Participant) Amendment Rules 2018 - F2018L00148 Prepared by the Department of Social Services Authorised Version F2018C00165 registered 22/03/2018 About this compilation This compilation This is a compilation of the National Disability Insurance Scheme (Becoming a Participant) Rules 2016 that shows the text of the law as amended and in force on 27 February 2018 (the compilation date). The notes at the end of this compilation (the endnotes) include information about amending laws and the amendment history of provisions of the compiled law. Uncommenced amendments The effect of uncommenced amendments is not shown in the text of the compiled law. Any uncommenced amendments affecting the law are accessible on the Legislation Register (www.legislation.gov.au). The details of amendments made up to, but not commenced at, the compilation date are underlined in the endnotes. For more information on any uncommenced amendments, see the series page on the Legislation Register for the compiled law. Application, saving and transitional provisions for provisions and amendments If the operation of a provision or amendment of the compiled law is affected by an application, saving or transitional provision that is not included in this compilation, details are included in the endnotes. Modifications If the compiled law is modified by another law, the compiled law operates as modified but the modification does not amend the text of the law. -

Government Gazette of the STATE of NEW SOUTH WALES Number 187 Friday, 28 December 2007

Government Gazette OF THE STATE OF NEW SOUTH WALES Number 187 Friday, 28 December 2007 Published under authority by Communications and Advertising Summary of Affairs FREEDOM OF INFORMATION ACT 1989 Section 14 (1) (b) and (3) Part 3 All agencies, subject to the Freedom of Information Act 1989, are required to publish in the Freedom of Information Government Gazette, an up-to-date Summary of Affairs. The requirements are specified in section 14 of Part 2 of the Freedom of Information Act. The Summary of Affairs has to contain a list of each of the Agency's policy documents, advice on how the agency's most recent Statement of Affairs may be obtained and contact details for accessing this information. The Summaries have to be published by the end of June and the end of December each year and need to be delivered to Communications and Advertising two weeks prior to these dates. CONTENTS LOCAL COUNCILS Page Page Page Armidale Dumaresq Council 429 Gosford City Council 567 Richmond Valley Council 726 Ashfield Municipal Council 433 Goulburn Mulwaree Council 575 Riverina Water County Council 728 Auburn Council 435 Greater Hume Shire Council 582 Rockdale City Council 729 Ballina Shire Council 437 Greater Taree City Council 584 Rous County Council 732 Bankstown City Council 441 Great Lakes Council 578 Shellharbour City Council 736 Bathurst Regional Council 444 Gundagai Shire Council 586 Shoalhaven City Council 740 Baulkham Hills Shire Council 446 Gunnedah Shire Council 588 Singleton Council 746 Bega Valley Shire Council 449 Gwydir Shire Council 592 -

National Harvest Guide July 2020

HaNationalrvest Guide Work your way around Australia July 2020 Work your way around Australia | 1 2 | National Harvest Guide Table of contents Introduction 3 Contact information New South Wales 13 If you have questions about this Guide please contact: Northern Territory 42 Harvest Trail Information Service Queensland 46 Phone: 1800 062 332 South Australia 77 Email: [email protected] Tasmania 96 or Victoria 108 Seasonal Work Programs Branch Department of Education, Skills Western Australia 130 and Employement Grain Harvest 147 GPO Box 9880 Canberra ACT 2601 Email: [email protected] Welcome to the national harvest guide Disclaimer A monthly updated version of the Guide ISSN 2652-6123 (print) is available on the Harvest Trail website ISSN 2652-6131 (online) www.harvesttrail.gov.au. Published July 2020 14th edition Revised July 2020 Information in this Guide may be subject to change due to the impact of COVID-19. A © Australian Government Department of guarantee to the accuracy of information Education, Skills and Employment 2020 cannot be given and no liability is accepted This publication is available for your use under a in the event of information being incorrect. Creative Commons BY Attribution 3.0 Australia licence, with the exception of the Commonwealth Coat of The Guide provides independent advice Arms, third party content and where otherwise stated. and no payment was accepted during The full licence terms are available from (https:// its publication in exchange for any listing creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au/legalcode). or endorsement of any place or business. The listing of organisations does not Use of the Commonwealth of Australia material under a Creative Commons BY Attribution 3.0 Australia licence imply recommendation. -

Dubbo City Regional Airport Master Plan 2019

18 September 2019 Mr Michael McMahon Chief Executive Officer Dubbo City Regional Council Sent by email: [email protected] [email protected] Regional Express Response to the Draft Master Plan for Dubbo City Regional Airport Dear Mr McMahon Regional Express (Rex) would like to thank Dubbo City Regional Council (DRC) for the opportunity to provide feedback to the 2019-2040 Dubbo City Airport Master Plan. Regional Express (Rex) was founded in 2002 as the merger of Ansett subsidiary airlines Hazelton and Kendell following the collapse of Ansett in 2001. Both Hazelton and Kendell airlines had over 30 years’ experience prior to the collapse of Ansett. Rex has serviced the City of Dubbo since Rex first commenced in 2002 and prior to that through its predecessor Hazelton. Rex is a dedicated regional airline that operates 60 Saab 340 turboprop aircraft (34 seats) to 60 destinations throughout Western Australia, South Australia, Victoria, Tasmania, New South Wales and Queensland. Rex carries around 1.3 million passengers on some 78,000 flights per year. Rex is a publicly listed company on the ASX. Rex with its more than 45 years of experience in regional aviation, the largest number of regional routes of any operator and the winner of the most State Government tenders for regulated routes is, without doubt, the pre-eminent authority on the operation, regulation and funding of air route service delivery to rural, regional and remote communities. As a dedicated regional airline Rex is solely focused on the provision of regional air services. Over the past 15 years Rex has been very successful in growing regional passenger numbers to record levels with Rex’s annual passenger numbers growing from around 600,000 in 2002/03 to around 1.3 million currently. -

Local Goverment Activities

APPENDIX 2C. LOCAL GOVERNMENT ACTIVITIES RELATED TO NATURAL RESOURCES MANAGEMENT Little River Catchment Management Plan - Stage I Report App 2c.0 A) PLANNING Wellington Shire Council The first Wellington Local Environment Plan (LEP) was implemented in 1987 followed by a second LEP gazetted in 1995. Declining population numbers due to property amalgamation are a problem within the Wellington Shire. The council has introduced a subdivision policy, which does not allow the construction of a second home on a property. This policy may potentially inhibit population growth within the Shire. Council has an active policy of trying to attract industry to the shire. Development Applications are not required for developments within the shire except for intensive development. The village of Yeoval is zoned as General Rural 1A by Wellington Shire, whereas the portion in Cabonne Shire is zoned Village. Wellington Council is collating much of their data, including some vegetation mapping, using the Geographical Information System - Map Info. Dubbo City Council The area west of the Little River and north of Toongi is the only part of the Little River Catchment within the Dubbo Shire. It is classified as Zone 1 A – General Rural. The Dubbo Local Environmental Plan 1997 - Rural Areas was gazetted in 1998 and Council plans to update this every five years. The City of Dubbo is covered by a separate LEP. This is to ensure that a buffer zone remains between the rural areas and the expanding urban area. Rural zones have a minimum of 800 ha, whereas urban areas are zoned in lots of 25 ha. -

Policy Committees Report NSW LABOR STATE CONFERENCE 2018 SATURDAY 30 JUNE and SUNDAY 1 JULY 2018 STATE CONFERENCE

Policy Committees Report NSW LABOR STATE CONFERENCE 2018 SATURDAY 30 JUNE AND SUNDAY 1 JULY 2018 STATE CONFERENCE POLICY COMMITTEE REPORT A Healthy Society Policy Committee Report…………………………………….………2 Australia and the World Policy Committee Report………………………………....…28 Building Sustainable Communities Policy Committee Report………………………50 Education and Skills Policy Committee Report…………………………………..…..125 Indigenous Peoples and Reconciliation Policy Committee Report…………..…...149 Our Economic Future Policy Committee Report……………………………..………156 Prosperity and Fairness at Work Policy Committee Report………………….……200 Social Justice and Legal Affairs Policy Committee Report…………………….….234 Country Labor Committee Report………………………………………………….…..292 1 2018 STATE CONFERENCE A HEALTHY SOCIETY The Australian Labor Party has a proud history of supporting the development of a good quality and accessible health system that goes back decades. Under Ben Chifley, Labor established the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme; Medibank under Gough Whitlam; and Medicare under Bob Hawke. At the State-level, the ALP has always worked to build a strong and inclusive public health service in NSW – providing a quality and accessible health and hospital system to all citizens regardless of their income. Sadly, both the Turnbull and Berejiklian Governments are attacking the health system built by Labor. They are reducing the quality and timeliness of clinical care and driving up costs in other parts of the health system. At a State and Federal level the Liberals and Nationals have slashed billions from the health and hospital system – culminating with the Turnbull Government recently slashing $715 million out of Australia’s public hospitals from 2017-2020. The current Liberal/National Governments have got their priorities all wrong at both the State and Federal levels given their billions of dollars in cuts from both our state public health system and our aged care industry. -

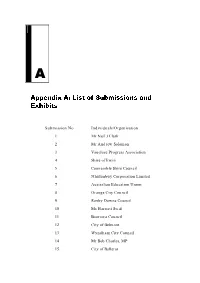

Appendix A: List of Submissions and Exhibits

A Appendix A: List of Submissions and Exhibits Submission No Individuals/Organisation 1 Mr Neil J Clark 2 Mr Andrew Solomon 3 Vaucluse Progress Association 4 Shire of Irwin 5 Coonamble Shire Council 6 Nhulunbuy Corporation Limited 7 Australian Education Union 8 Orange City Council 9 Roxby Downs Council 10 Ms Harriett Swift 11 Boorowa Council 12 City of Belmont 13 Wyndham City Council 14 Mr Bob Charles, MP 15 City of Ballarat 148 RATES AND TAXES: A FAIR SHARE FOR RESPONSIBLE LOCAL GOVERNMENT 16 Hurstville City Council 17 District Council of Ceduna 18 Mr Ian Bowie 19 Crookwell Shire Council 20 Crookwell Shire Council (Supplementary) 21 Councillor Peter Dowling, Redland Shire Council 22 Mr John Black 23 Mr Ray Hunt 24 Mosman Municipal Council 25 Councillor Murray Elliott, Redland Shire Council 26 Riddoch Ward Community Consultative Committee 27 Guyra Shire Council 28 Gundagai Shire Council 29 Ms Judith Melville 30 Narrandera Shire Council 31 Horsham Rural City Council 32 Mr E. S. Cossart 33 Shire of Gnowangerup 34 Armidale Dumaresq Council 35 Country Public Libraries Association of New South Wales 36 City of Glen Eira 37 District Council of Ceduna (Supplementary) 38 Mr Geoffrey Burke 39 Corowa Shire Council 40 Hay Shire Council 41 District Council of Tumby Bay APPENDIX A: LIST OF SUBMISSIONS AND EXHIBITS 149 42 Dalby Town Council 43 District Council of Karoonda East Murray 44 Moonee Valley City Council 45 City of Cockburn 46 Northern Rivers Regional Organisations of Councils 47 Brisbane City Council 48 City of Perth 49 Shire of Chapman Valley 50 Tiwi Islands Local Government 51 Murray Shire Council 52 The Nicol Group 53 Greater Shepparton City Council 54 Manningham City Council 55 Pittwater Council 56 The Tweed Group 57 Nambucca Shire Council 58 Shire of Gingin 59 Shire of Laverton Council 60 Berrigan Shire Council 61 Bathurst City Council 62 Richmond-Tweed Regional Library 63 Surf Coast Shire Council 64 Shire of Campaspe 65 Scarborough & Districts Progress Association Inc. -

Government Gazette

6591 Government Gazette OF THE STATE OF NEW SOUTH WALES Number 111 Friday, 18 November 2011 Published under authority by Government Advertising LEGISLATION Online notification of the making of statutory instruments Week beginning 7 November 2011 THE following instruments were officially notified on the NSW legislation website(www.legislation.nsw.gov.au) on the dates indicated: Regulations and other statutory instruments Pawnbrokers and Second-hand Dealers Amendment (Licence Exemptions) Regulation 2011 (2011-584) — published LW 11 November 2011 Water Management (Application of Act to Certain Water Sources) Proclamation (No 2) 2011 (2011-576) — published LW 11 November 2011 Water Management (General) Amendment (Water Sharing Plans) Regulation (No 2) 2011 (2011-577) — published LW 11 November 2011 Water Sharing Plan for the Intersecting Streams Unregulated and Alluvial Water Sources 2011 (2011-573) — published LW 11 November 2011 Water Sharing Plan for the NSW Great Artesian Basin Groundwater Sources Amendment Order 2011 (2011-574) — published LW 11 November 2011 Water Sharing Plan for the NSW Great Artesian Basin Shallow Groundwater Sources 2011 (2011-575) — published LW 11 November 2011 Environmental Planning Instruments Bellingen Local Environmental Plan 2010 (Amendment No 1) (2011-578) — published LW 11 November 2011 Cessnock Local Environmental Plan 1989 (Amendment No 126) (2011-585) — published LW 11 November 2011 Culcairn Local Environmental Plan 1998 (Amendment No 3) (2011-579) — published LW 11 November 2011 Dubbo Local Environmental -

Macquarie Community Profile: Irrigation Region

Macquarie community profile Irrigation region Key issues for the region 1. Region’s population: The Macquarie irrigation region comprises an area of some 13,000km2 in central west New South Wales covering three council areas,- Dubbo City and the shires of Narromine and Warren. The area has a total population of 47,000 people, of whom 37,000 live in the City of Dubbo. Outside Dubbo, the region is highly reliant on agriculture for employment and wealth creation, with most employment in the irrigation districts especially in cotton. The region is also a centre for cereal cropping and is famous for its Merino studs. Agriculture supports a wide range of services in the public and private sectors. 2. Water entitlements • Surface Water Long-term Cap — The Water Sharing Plan for the Macquarie and Cudgegong Regulated Rivers Water Source took effect on 1 July 2004. This limits average annual extractions to 391,900 ML. • Water entitlements for the Macquarie region are as follows: High Security (15,038 ML); General Security (611,271 ML); Environmental Water Allowance (160,000 ML); Supplementary Water (48,505 ML); Domestic and Stock water (4,826 ML); Local Water Utility (16,205 ML); Groundwater entitlements (65,524 ML). These figures refer solely to the entitlements available from the Macquarie River serviced out of Burrendong Dam. They ignore entitlements available from the Cudgegong supplied out of Lake Windamere. 3. Major enterprises — Cotton has been a major employer across the region since the 1980s, both in primary production and in processing, with five gins located at strategic points across the region. -

Dubbo City Holiday Park

1 2 3 4 5 VANDALISM COST REPORT FOR JUNE 2017 Division – 2010/2011 2011/2012 2012/2013 2013/2014 2014/2015 2015/2016 2016/2017 vandalism costs Parks and $37,048.90 $26,742.68 $49,120.65 $84,396.83 $46,972.98 $46,388.97 $44,899.77 Landcare Technical $30,077.95 $23,522.30 $15,495.97 $14,318.54 $14,596.59 $15,930.62 $13,624.97 Services Corporate $6,757.00 $8,156.10 $3,342.27 $617.50 $983.16 $1,563.64 NIL Development Community $4,536.01 $7,957.00 $1,889.63 $1,262 $786.82 $216.62 $2,300.59 Services Organisational N/A N/A N/A N/A N/A N/A N/A Services Environmental N/A $1,091.91 $600 $1,694 $801 $2,000 $1,010 Services Wellington N/A N/A N/A N/A N/A N/A $19,362.55 Total $78,419.86 $67,469.99 $70,448.52 $102,288.87 $64,140.55 $66,099.85 $81,197.88 Rewards Nil Nil Nil 1 ($2,500) Nil Nil Nil approved 6 7 DUBBO REGIONAL COUNCIL SUMMARISED STATEMENT OF RESTRICTED ASSETS AS AT 30 JUNE 2017 PURPOSE OF INTERNALLY RESTRICTED ASSET FUNCTION BALANCE TRANSFERS TRANSFERS BALANCE AS AT TO FROM AS AT 01/07/2016 2016/2017 2016/2017 30/06/2017 General Footpaths & Cycleways 1.07 456,208 327,226 216,589 566,845 Traffic Management 1.10 71,461 54,339 0 125,800 Street Lighting 1.11 427,025 34,436 0 461,461 Road Network - State Roads 1.201 774,229 538,119 0 1,312,348 Road Network - Urban Roads 1.202 1,425,193 5,016,104 1,010,177 5,431,120 Road Network - Rural Roads 1.203 4,117,213 1,819,424 1,358,778 4,577,859 Other Waste Management Services 2.07 3,718,052 64,426 20,300 3,762,178 Stormwater 4.01 13,553 0 0 13,553 Fire Services 4.02 531,992 1,350 51,685 481,657 Emergency -

Local Government (Council Amalgamations) Proclamation 2016 Under the Local Government Act 1993

New South Wales Local Government (Council Amalgamations) Proclamation 2016 under the Local Government Act 1993 DAVID HURLEY, Governor I, General The Honourable David Hurley AC DSC (Ret’d), Governor of New South Wales, with the advice of the Executive Council, and in pursuance of Part 1 of Chapter 9 of the Local Government Act 1993, make the following Proclamation. Signed and sealed at Sydney, this 12th day of May 2016. By His Excellency’s Command, PAUL TOOLE, MP Minister for Local Government GOD SAVE THE QUEEN! Explanatory note The object of this Proclamation is to constitute and amalgamate various local government areas and to make consequential savings and transitional provisions. Published LW 12 May 2016 at 12.10 pm (2016 No 242) Local Government (Council Amalgamations) Proclamation 2016 [NSW] Contents Contents Page Part 1 General 1 Name of Proclamation 4 2 Commencement 4 3 Definitions 4 4 Amalgamated areas 5 5 Matters or things to be determined by Minister 5 6 References to former areas and councils 6 7 Powers under Act 6 8 County councils 6 9 Planning panels 6 Part 2 Operations of councils Division 1 Preliminary 10 Definitions 7 Division 2 Governance 11 First election 7 12 Administrators for new councils 7 13 Vacation of office by Administrators 8 14 Interim general managers and deputy general managers 8 15 Election of mayor following first election 9 Division 3 Council activities 16 Obligations of new councils 9 17 Activities of former councils 9 18 Delegations 9 19 Codes, plans, strategies and policies 9 20 Code of conduct 9 21