'No Longer Slaves, but Beloved Brothers and Sisters'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

"Man-Patron" Relationship in Contemporary Northeast Brazil" (1972)

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 1972 Continuity of a traditional social pattern: the "man- patron" relationship in contemporary northeast Brazil Patricia Ellen Thorpe Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, Nature and Society Relations Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Thorpe, Patricia Ellen, "Continuity of a traditional social pattern: the "man-patron" relationship in contemporary northeast Brazil" (1972). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 958. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.958 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. AN A3ST?~CT OF THE THESIS OF Patricia Ellen Thorpe for the Master of Arts in Anthropology presented October 24, 1972. Title: Continuity of A Traditional Social Pattern: The "Man-Patronlt Relationship in Contemporary Northeast Brazil .. APPROVED BY MEMBERS OF THE THESIS COMMITTEE: zr~COb Fried, Chairman Daniel/Scheans Tom Ne\-nnan Northeast Brazil is a region characterized by economic poverty and human misery. Poor ecological conditions con tribute to the nature of the dilemma, but another factor in the apparent cultural stagnation of the Northeast, may be the persistence of values and social practices traditiona.lly alig!1ed with the colonial sugar plantation system. Thus, this thesis represents e~ examination of the continuity of a given pattern, the man/patron relationship. -

Zallen Gsas.Harvard 0084L 11460.Pdf (8.379Mb)

American Lucifers: Makers and Masters of the Means of Light, 1750-1900 The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Zallen, Jeremy Benjamin. 2014. American Lucifers: Makers and Masters of the Means of Light, 1750-1900. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:12274111 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA American Lucifers: Makers and Masters of the Means of Light, 1750-1900 A dissertation presented by Jeremy Benjamin Zallen to The Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of History Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts April 2014 ©2014—Jeremy Benjamin Zallen All rights reserved. American Lucifers: Makers and Masters of the Means of Light, 1750-1900 Abstract This dissertation examines the social history of Atlantic and American free and unfree labor by focusing on the production and consumption of the means of light from the colonial period to the end of the nineteenth century. Drawing from archives across the country, I reconstruct the ground-level experiences and struggles of the living (and dying) bringers of lights—those American lucifers—and the worlds they made in the process. I begin by arguing that colonial American deep-sea whaling voyages triggered an Atlantic street lighting revolution radiating from London, while a New England run candles-for-slave(ry) trade helped illuminate and circulate processes caught up in colonial transatlantic sugar slavery. -

Central African Identities and Religiosity in Colonial Minas Gerais 2012

Kalle Kananoja Central African Identities and Religiosity in Colonial Minas and Religiosity Identities African in Colonial Gerais Central Kalle Kananoja Central African Identities and Religiosity in Colonial Minas Gerais 2012 Åbo Akademi University | ISBN 978-952-93-0489-9 Central African Identities and Religiosity in Colonial Minas Gerais Kalle Kananoja Åbo Akademi University / 2012 © Kalle Kananoja Author’s address: Department of History Åbo Akademi University Fabriksgatan 2 FI-20500 Åbo Finland e-mail: [email protected] ISBN 978-952-93-0489-9 (paperback) ISBN 978-952-93-0490-5 (PDF) Printed by Uniprint, Turku Table of Contents Maps ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� i Acknowledgments ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������iii 1 Introduction ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 1 1.1 Main Issues and Aims of the Study ....................................................... 1 1.2 Overview of the Literature �������������������������������������������������������������������� 4 1.2.1 The Slave Trade between Angola and Brazil and its Cultural Implications ......................................................... 4 1.2.2 Africans and Their Descendants in Mineiro Society ..................... 8 1.3 African Identities in Colonial Brazil.....................................................11 1.4 Creolization and Syncretism in the Southern Atlantic -

Please Let Our Elder Team, Staff Team, and Prayer Team Know How We Can Be Praying with You and for You This Week

Please let our Elder Team, Staff Team, and Prayer Team know how we can be praying with you and for you this week: 300 east main street | johnson city, tn 37601 | 423-302-0346 | redeemercommunity.com WELCOME TO THE REDEEMER COMMUNITY REDEEMER STAFF TEAM CONNECT CARD Look around you this morning, and you'll find a sea of others who are here because they Steven Blackburn | Community Life Pastor January 26, 2020 too have found they're in need of more than our world or our culture can offer. So welcome, [email protected] whether you are a first or second-time guest, you attend our gatherings regularly, or you Chris Eger | Executive Director & Worship Pastor call Redeemer your people. We hope you'll witness God among us this morning through [email protected] singing and praying, studying scripture and sharing communion, or just through all these Jim Fickley | Equipping Pastor fellow ragamuffins who came, too. Settle in, get some coffee, and extend a hand of kindness [email protected] to someone around you as together we all settle into the Redeemer fold this morning! Jeff Martin | Lead Pastor [email protected] OUR MISSION Leya Martinez | Executive Assistant & Event Host Our mission is to enjoy Christ, love His friends, and engage our world. We do this first by [email protected] applying the Gospel of Jesus to our everyday lives. We are also focused on carrying out this Blake Sanders | Student Minister ____________________ Special Events Special Team Prayer Communion & Coffee ____________________ mission locally and globally. Check out who we’re working alongside on page 7. -

Großbritannien 1994

Kieler Beiträge zur Filmmusikforschung, 5.3, 2010 // 407 COME HELL OR HIGH WATER Großbritannien 1994 R: Hugh Symonds. P: Heinz Henn, Lana Topham. K: David Amphlett. S: Niven Howie. T: Chris McDermott. Beteiligte Bands: Deep Purple. DVD-/Video-Vertrieb: BMG Video. Video-Auslieferung: Oktober 1994 (Großbritannien). DVD-Auslieferung: 29.05.2001 (Großbritannien). 124min, 1,33:1, Farbe, Dolby Digital 2.0 Stereo/Dolby Digital 5.1. „Es würde mehr Spaß machen, mit Saddam Hussein auf der Bühne zu stehen als mit Ian Gillan,“ erklärte Ritchie Blackmore nach seinem zweiten und endgültigen Abschied von Deep Purple im Jahr 1993 [1]. Die Spannungen zwischen dem Sänger Gillan und dem Gitarristen Blackmore sorgten immer wieder für Probleme in der Band, förderten gleichzeitig aber auch die Kreativität der Mark II genannten Besetzung Ian Gillan (Gesang), Ritchie Blackmore (Gitarre), Jon Lord (Orgel/Keyboard), Roger Glover (Bass) und Ian Paice (Schlagzeug), die von 1969 bis 1973, 1984 bis 1989 sowie 1992 bis 1993 gemeinsam aktiv war. Insgesamt existierten von der Bandgründung im Jahr 1968 bis heute zehn verschiedene Line-Ups, betitelt mit Mark I bis Mark X. Der größte Erfolg war dabei, gemessen an Platten- und Ticketverkäufen, stets Mark II beschieden. Auch die großen Hits der Band wie Highway Star, Perfect Strangers oder das weltbekannte Smoke On The Water stammen von dieser Besetzung, in anderen Konstellationen war die Gruppe verhältnismäßig unproduktiv. Die Rivalitäten zwischen Gillan und Blackmore führten immer wieder dazu, dass einer von beiden Deep Purple verließ – in der Regel der Sänger Gillan (so geschehen 1973 und 1989), den Blackmore – er war Gründungsmitglied der Formation – weniger als vollwertiges Bandmitglied, sondern vielmehr als bezahlten Sänger betrachtete, den man nach Belieben ersetzen konnte. -

History in the Making 2013

HISTORY IN THE MAKING California State University, San Bernardino Journal of History Volume Six 2013 Alpha Delta Nu Chapter, Phi Alpha Theta National History Honor Society History in the Making is an annual publication of the California State University, San Bernardino (CSUSB) Alpha Delta Nu Chapter of the Phi Alpha Theta National History Honor Society, and is sponsored by the History Department and the Instructionally Related Programs at CSUSB. Issues are published at the end of the spring quarter of each academic year. Phi Alpha Theta’s mission is to promote the study of history through the encouragement of research, good teaching, publication and the exchange of learning and ideas among historians. The organization seeks to bring students, teachers and writers of history together for intellectual and social exchanges, which promote and assist historical research and publication by our members in a variety of ways. Copyright © 2013 Alpha Delta Nu, California State University, San Bernardino. Original cover art by Caitlin Barber, Copyright © 2013 History in the Making History in the Making Table of Contents Introduction _________________________________________ v Acknowledgements ____________________________________ ix Editorial Staff ________________________________________ xi Articles A Historiography of Fascism by Glenn-Iain Steinbeck ________________________________ 1 Black Stand-Up Comedy of the 1960s by Claudia Mariscal __________________________________ 27 Shared Spaces, Separate Lives: Community Formation in the California Citrus Industry during the Great Depression by David Shanta _____________________________________ 57 California and Unfree Labor: Assessing the Intent of the 1850 “An Act for the Government and Protection of Indians” by Aaron Beitzel ____________________________________ 101 Imagining Margaret Garner: The Tragic Life of an American Woman by Cecelia M. -

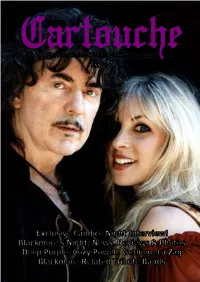

Cartouche Issue 1

The Free Online Ritchie Blackmore Fanzine Editorial Contents Pages Hello Blackmore fans, Blackmore’s Night News Roundup……….. 3, 4 Blackmore’s Night Tour Dates……………. 5 Our idea is to produce a free Ritchie Blackmore Shadow of the Moon – First Impressions…. 6 fanzine, which involves putting the resultant Club de Official de BN Fans en Espana…… 7 JPEG fanzine pages onto certain fan forum boards, so Blackmore’s Night Polish Street Team……. 8 that fans can read them and /or copy the pages to their An Interview with Candice Night…………. 9 – 15 own computers and thus print out the pages at home. 10 Years of Blackmore’s Night……………. 16 We thus present to you, a trial issue to see if the idea Blackmore’s Night: A Personal Perspective. 17, 18 works. Blackmore’s Night: 1999 – 2008………….. 19 Blackmore’s Night is running out of Ideas? 20 Thank you so much, to the fans that have contributed to 10 Anni di Blackmore’s Night…………….. 21 this project already and also especially, to Candice “Paris Moon” Reviewed…………………… 22 Night who gave us some brilliant and comprehensive A Trip to Paris……………………………... 23 interview answers! “The Next Stage” Reviewed………………. 25 2007 UK Tour Diary………………………. 26 – 34 Editor: Mike Garrett Morning Star - BN Tribute Band ………… 36, 37 [email protected] An Interview with LA ZAG……………… 38, 39 “Still I’m Sad” – A Tribute to Cozy Powell. 40 – 43 Deputy Editor: Kevin Dixon What if RJD had joined Deep Purple?…….. 44 [email protected] “Ritchie Blackmore’s Rainbow” retrospect.. 45, 46 Deep Purple – Is the colour fading?………. -

Cape Verde Islands, C. 1500–1879

TRANSFORMATION OF “OLD” SLAVERY INTO ATLANTIC SLAVERY: CAPE VERDE ISLANDS, C. 1500–1879 By Lumumba Hamilcar Shabaka A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of History- Doctor of Philosophy 2013 ABSTRACT TRANSFORMATION OF “OLD” SLAVERY INTO ATLANTIC SLAVERY: CAPE VERDE ISLANDS, C. 1500–1879 By Lumumba Hamilcar Shabaka This dissertation explores how the Atlantic slave trade integrated the Cape Verde archipelago into the cultural, economic, and political milieu of Upper Guinea Coast between 1500 and 1879. The archipelago is about 300 miles off the coast of Senegal, West Africa. The Portuguese colonized the “uninhabited” archipelago in 1460 and soon began trading with the mainland for slaves and black African slaves became the majority, resulting in the first racialized Atlantic slave society. Despite cultural changes, I argue that cultural practices by the lower classes, both slaves and freed slaves, were quintessentially “Guinean.” Regional fashion and dress developed between the archipelago and mainland with adorning and social use of panu (cotton cloth). In particular, I argue Afro-feminine aesthetics developed in the islands by freed black women that had counterparts in the mainland, rather than mere creolization. Moreover, the study explores the social instability in the islands that led to the exile of liberated slaves, slaves, and the poor, the majority of whom were of African descent as part of the Portuguese efforts to organize the Atlantic slave trade in the Upper th Guinea Coast. With the abolition of slavery in Cape Verde in the 19 century, Portugal used freed slaves and the poor as foot soldiers and a labor force to consolidate “Portuguese Guinea.” Many freed slaves resisted this mandatory service. -

Devotional Series: the Value of Family Family— a Divine Appointment by Leanna Simpson, Agape Executive Director

Devotional Series: The Value of Family Family— a Divine Appointment By Leanna Simpson, Agape Executive Director I SAMUEL 1:10A “And Hannah made this vow: “O Lord of Heaven’s Armies, if you will look upon my sorrow and answer my prayer and give me a son, then I will give him back to you. He will be yours for his entire lifetime...” When I think about God’s orchestration and making of a family, I think of this passage. There are so many truths and weighted complexities that come from this story of Hannah, who is praying and pleading for a child. First, she is acknowledging that only God can choose to give each of us the gift of a child and He ordains it. Whether we have carried this child or taken them in as our own, they were created by God and we have been commissioned with their rearing. Second, a child is not our possession but a gift that should be stewarded and guided as a gift on “loan” from God for a season. Every child we are given was uniquely placed and designed to be a part of our family. There are no mistakes or coincidences with God. Thirdly, a child is neither created or designed by us and their future should not be either. It is a great burden to steward a child. As they are a creation by the Divine Creator, it is with great gravity that we should forever and always understand that we must “give them back to God” and raise them up to know what is righteous and true through the grid of the Scriptures. -

Praise & Worship

PRAISE & WORSHIP Cathedral of Mary of the Assumption, Saginaw, MI • August 13, 2021 • 6 PM Good Good Father Holy Spirit To tell You there's no better place V1) I've heard a thousand stories V1) There's nothing worth more that will For me than in Your arms Of what they think You’re like ever come close; No thing can compare, To tell You I'm sorry But I've heard the tender whisper You're our living hope: Your Presence or running in circles Of love in the dead of night For placing my focus on the waves You tell me that You’re pleased Verse 2) I've tasted and seen of the not on Your face And that I'm never alone sweetest of loves You're the only one who brings me Where my heart becomes free, and my peace (repeat) (repeat from top, then:) Chorus) You're a Good, Good Father shame is undone: in Your Presence Lord In the storm, In the storm It's who You are, It's who You are It's who You are, and I'm loved by You Chor) Holy Spirit, You are welcome here CCLI Song # 5910881 Will Reagan © 2008 Capitol CMG Genesis Come flood this place and fill the (Admin. by Capitol CMG Publishing) United Pursuit Music (Admin. by It's who I am, It's who I am, It's who I am Capitol CMG Publishing) For use solely with the SongSelect® Terms atmosphere; Your glory, God, is what of Use. All rights reserved. -

SECOND SUNDAY in LENT February 28, 2021 - 10:30 AM

SECOND SUNDAY IN LENT February 28, 2021 - 10:30 AM Pre-Service “The Blood of Jesus Speaks for Me” “The Lion and the Lamb” WELCOME & GREETING OPENING SONG “The Blood of Jesus Speaks for Me” Vs.1 The blood of Jesus speaks for me Bridge Worthy is the Lamb Lamb for sinners slain Be still my soul redeeming love Jesus Lord of all glory to His name Out of the dust of Calvary Heaven crying out let the earth proclaim Is rising to the throne above Power in the blood glory to His name There is no vengeance in His cry (Repeat) While it is finished fills the sky Jesus Forgiveness is the final plea Vs.4 Oh let my soul arise and sing The blood of Jesus speaks for me My confidence is not in vain Vs.2 My heart can barely take it in The One who fights for me is King He pardons all my guilty stains His oath His covenant remain Surrender all my shame to Him No condemnation now I dread He breaks the curse of ev'ry chain Eternal hope is mine instead My sin is great but greater still His Word will stand I stand redeemed The boundless grace His heart reveals The blood of Jesus speaks for me A mercy deeper than the sea The blood of Jesus speaks for me Ending Amazing love how can it be The blood of Jesus speaks for me Vs.3 When my accuser makes the claim For me That I should die for my offense For me I point him to that rugged frame Where I found life at Christ's expense See from His hands His feet His side The fountain flowing deep and wide Oh hear it shout the victory The blood of Jesus speaks for me CCLI Song # 7057451, David Moffitt | Travis Cottrell, © Great Revelation Music (Admin.