Struggling to Make a Living

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Section-VIII : Laboratory Services

Section‐VIII Laboratory Services 8. Laboratory Services 8.1 Haemoglobin Test ‐ State level As can be seen from the graph, hemoglobin test is being carried out at almost every FRU studied However, 10 percent medical colleges do not provide the basic Hb test. Division wise‐ As the graph shows, 96 percent of the FRUs on an average are offering this service, with as many as 13 divisions having 100 percent FRUs contacted providing basic Hb test. Hemoglobin test is not available at District Women Hospital (Mau), District Women Hospital (Budaun), CHC Partawal (Maharajganj), CHC Kasia (Kushinagar), CHC Ghatampur (Kanpur Nagar) and CHC Dewa (Barabanki). 132 8.2 CBC Test ‐ State level Complete Blood Count (CBC) test is being offered at very few FRUs. While none of the sub‐divisional hospitals are having this facility, only 25 percent of the BMCs, 42 percent of the CHCs and less than half of the DWHs contacted are offering this facility. Division wise‐ As per the graph above, only 46 percent of the 206 FRUs studied across the state are offering CBC (Complete Blood Count) test service. None of the FRUs in Jhansi division is having this service. While 29 percent of the health facilities in Moradabad division are offering this service, most others are only a shade better. Mirzapur (83%) followed by Gorakhpur (73%) are having maximum FRUs with this facility. CBC test is not available at Veerangna Jhalkaribai Mahila Hosp Lucknow (Lucknow), Sub Divisional Hospital Sikandrabad, Bullandshahar, M.K.R. HOSPITAL (Kanpur Nagar), LBS Combined Hosp (Varanasi), -

A Study of Faizabad Division in Eastern Uttar Pradesh

Journal of Pharmacognosy and Phytochemistry 2018; SP2: 273-277 E-ISSN: 2278-4136 P-ISSN: 2349-8234 National Conference on Conservation Agriculture JPP 2018; SP2: 273-277 (ITM University, Gwalior on 22-23 February, 2018) Sandhya Verma N.D. University of Agriculture & Technology, Kmarganj, Developmental dynamics of blocks: A study of Faizabad, U.P, India Faizabad division in Eastern Uttar Pradesh BVS Sisodia N.D. University of Agriculture & Technology, Kmarganj, Sandhya Verma, BVS Sisodia, Manoj Kumar Sharma and Amar Singh Faizabad, U.P, India Abstract Manoj Kumar Sharma SKN College of Agriculture, Sri The development process of any system is dynamic in nature and depends on a large number of Karan Narendra Agriculture parameters. This study attempted to capture latest dynamics of development of blocks of Faizabad University, Jobner, Jaipur, division of Eastern Uttar Pradesh in respect of Agriculture and Infrastructure systems. Techniques Rajasthan, India adopted by Narain et al. have been used in addition to Principal Component and Factor Analysis. Ranking of the blocks in respect of performance in Agriculture, General Infrastructure and Industry have Amar Singh been obtained in this study. Ranking seems to very close to ground reality and provides useful ITM University, Gwalior, M.P, information for further planning and corrective measures for future development of blocks of Faizabad India division of Eastern Uttar Pradesh. Keywords: Developmental Indicator, composite index, Principal component analysis, Socioeconomic, Factor analysis Introduction Development is a dynamic concept and has a different meaning for different people. It is used in many disciplines at present. The notion of development in the context of regional development refers to a value positive concept which aims to enhance the levels of living of the people and general conditions of human welfare in a region. -

National Highways Authority of India

a - = ----- f- -~ - |l- National HighwaysAuthority of India (Ministry of Road Transport & Highways) New Delhi, India _, Public Disclosure Authorized Final Generic EMP: Lucknow- Ayodhya Stretch on NH-28 and Gorakhpur Bypass August, 2004 E895 Volume 4 Public Disclosure Authorized -F~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~-r Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized fl4V enmiltennt± ILArD f'~-em. .I,iuv*e D A 1 Iii 4~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~40 Shri V.K. Sharma General Manager DHV Consultants Social & Environmental Development Unit Branch Office National Highway Authority of India C-154, Greater Kailash-I Plot No. G 5 & G 6 New Delhio- 110 048 Sector - 10, Dwarka Telephone +91-11-646 643316455/5744 New Delhi Fax +91-11-622 6543 E-mail:[email protected] New Delhi, 10OhAugust 2004 Our Ref. MSP/NHAI/0408.094 Subject Submission of Final Report: Independent Review of EIA, EMIPand EA * Process Summary for Lucknow-Ayodhya section of NH-28 and Gorakhpur Bypass Project * Dear Sir, We are submitting the Final Report of Independent Review of EIA, EMP and EA Process Sumnmaryfor Lucknow Ayodhya section of NH-28 and Gorakhpur Bypass Project for your kind consideration. We hope you would appreciate our efforts in carrying out the assignment. Thanking you, Yours s iferely DHV C ultan M.S. Prakash (Dr. Team Leader l l I D:\UmangWH-28FiraReport August 10 doc\covoumglt doe DHVConsultants Is partof the DHVGroup. Laos, t .-. n rntarnalaHuncarv. Hona Kona. rIndia, Inronesi, Israel, Kenya. I(*$Ž4umg I - o-o- ....... 0. Q-io...,. GenericEnvironmental Management Plan for Lucknow- Ayodhyasection of | NH-28and Gorakhpurbypass I'1if-s a] an I 3Leiito]3 a ,"I .m.D3Vy3 II . -

ALLAHABAD Address: 38, M.G

CGST & CENTRAL EXCISE COMMISSIONERATE, ALLAHABAD Address: 38, M.G. Marg, Civil Lines, Allahabad-211 001 Phone: 0532-2407455 E mail:[email protected] Jurisdiction The territorial jurisdiction of CGST and Central Excise Commissionerate Allahabad, extends to Districts of Allahabad, Banda, Chitrakoot, Kaushambi, Jaunpur, SantRavidas Nagar, Pratapgarh, Raebareli, Fatehpur, Amethi, Faizabad, Ambedkarnagar, Basti &Sultanpurof the state of Uttar Pradesh. The CGST & Central Excise Commissionerate Allahabad comprises of following Divisions headed by Deputy/ Assistant Commissioners: 1. Division: Allahabad-I 2. Division: Allahabad-II 3. Division: Jaunpur 4. Division: Raebareli 5. Division: Faizabad Jurisdiction of Divisions & Ranges: NAME OF JURISDICTION NAME OF RANGE JURISDICTION OF RANGE DIVISION Naini-I/ Division Naini Industrial Area of Allahabad office District, Meja and Koraon tehsil. Entire portion of Naini and Karchhana Area covering Naini-II/Division Tehsil of Allahabad District, Rewa Road, Ranges Naini-I, office Ghoorpur, Iradatganj& Bara tehsil of Allahabad-I at Naini-II, Phulpur Allahabad District. Hdqrs Office and Districts Jhunsi, Sahson, Soraon, Hanumanganj, Phulpur/Division Banda and Saidabad, Handia, Phaphamau, Soraon, Office Chitrakoot Sewait, Mauaima, Phoolpur Banda/Banda Entire areas of District of Banda Chitrakoot/Chitrako Entire areas of District Chitrakoot. ot South part of Allahabad city lying south of Railway line uptoChauphatka and Area covering Range-I/Division Subedarganj, T.P. Nagar, Dhoomanganj, Ranges Range-I, Allahabad-II at office Dondipur, Lukerganj, Nakhaskohna& Range-II, Range- Hdqrs Office GTB Nagar, Kareli and Bamrauli and III, Range-IV and areas around GT Road. Kaushambidistrict Range-II/Division Areas of Katra, Colonelganj, Allenganj, office University Area, Mumfordganj, Tagoretown, Georgetown, Allahpur, Daraganj, Alopibagh. Areas of Chowk, Mutthiganj, Kydganj, Range-III/Division Bairahna, Rambagh, North Malaka, office South Malaka, BadshahiMandi, Unchamandi. -

Statistical Diary, Uttar Pradesh-2020 (English)

ST A TISTICAL DIAR STATISTICAL DIARY UTTAR PRADESH 2020 Y UTT AR PR ADESH 2020 Economic & Statistics Division Economic & Statistics Division State Planning Institute State Planning Institute Planning Department, Uttar Pradesh Planning Department, Uttar Pradesh website-http://updes.up.nic.in website-http://updes.up.nic.in STATISTICAL DIARY UTTAR PRADESH 2020 ECONOMICS AND STATISTICS DIVISION STATE PLANNING INSTITUTE PLANNING DEPARTMENT, UTTAR PRADESH http://updes.up.nic.in OFFICERS & STAFF ASSOCIATED WITH THE PUBLICATION 1. SHRI VIVEK Director Guidance and Supervision 1. SHRI VIKRAMADITYA PANDEY Jt. Director 2. DR(SMT) DIVYA SARIN MEHROTRA Jt. Director 3. SHRI JITENDRA YADAV Dy. Director 3. SMT POONAM Eco. & Stat. Officer 4. SHRI RAJBALI Addl. Stat. Officer (In-charge) Manuscript work 1. Dr. MANJU DIKSHIT Addl. Stat. Officer Scrutiny work 1. SHRI KAUSHLESH KR SHUKLA Addl. Stat. Officer Collection of Data from Local Departments 1. SMT REETA SHRIVASTAVA Addl. Stat. Officer 2. SHRI AWADESH BHARTI Addl. Stat. Officer 3. SHRI SATYENDRA PRASAD TIWARI Addl. Stat. Officer 4. SMT GEETANJALI Addl. Stat. Officer 5. SHRI KAUSHLESH KR SHUKLA Addl. Stat. Officer 6. SMT KIRAN KUMARI Addl. Stat. Officer 7. MS GAYTRI BALA GAUTAM Addl. Stat. Officer 8. SMT KIRAN GUPTA P. V. Operator Graph/Chart, Map & Cover Page Work 1. SHRI SHIV SHANKAR YADAV Chief Artist 2. SHRI RAJENDRA PRASAD MISHRA Senior Artist 3. SHRI SANJAY KUMAR Senior Artist Typing & Other Work 1. SMT NEELIMA TRIPATHI Junior Assistant 2. SMT MALTI Fourth Class CONTENTS S.No. Items Page 1. List of Chapters i 2. List of Tables ii-ix 3. Conversion Factors x 4. Map, Graph/Charts xi-xxiii 5. -

Barabanki Dealers Of

Dealers of Barabanki Sl.No TIN NO. UPTTNO FIRM - NAME FIRM-ADDRESS 1 09150600003 BB0010297 J.R.ORGAINIC INDUSTRIES LTD. DEWA ROAD BARABANKKI 2 09150600017 BB0019725 POINEER MEDICAL STORE BEGAM GANJ BARABANKI 3 09150600022 BB0027709 PAL CYCLE HOUSE LAIYA MANDI BARABANKI 4 09150600036 BB0029230 SAMSHUDIN SARRPHUDIN SADAR BAZAR BARABANKI 5 09150600041 BB0034599 TRILOCHAN NATH KESHAO KUMAR SAFDAR GANJ BARABANKI 6 09150600055 BB0016832 SHYAM BIHARI RAM SWROOP JAISWAL DHANOKHAR CHOURAHA BARABANKI 7 09150600060 BB0037812 MATA PRASAD BHURA MALL GALLA FATEHPUR BARABANKI 8 09150600069 BB0041040 GUPTA FERTILIZER FATEHPUR BARABANKI 9 09150600074 BB0041380 HARI TEE CO. MAIN ROAD BARABANKI 10 09150600088 BB0042964 UNITED DRUG AGENCIES MEENA MARKET BARABANKI 11 09150600093 BB0088502 LAXMI RICE MILL & ALLIED INDUSTRIES FAIZABAD ROAD BARABANKI 12 09150600102 BB0049211 RAM PRAKASH CONTRACTION TIKRA BADDUPUR BARABANKI 13 09150600116 BB0046957 KISAN COLD STORAGE PALHARI CHOURAHA BARABANKI 14 09150600121 BB0046900 BEAUTY PALACE GENERAL MERCHANT, 34 INDIRA MARKET BARABANKI 15 09150600135 BB0048714 FATEHPUR TRADING CO. FATEHPUR BARABANKI 16 09150600140 BB0030073 RINKU COAL DEPOT NAKA SATARAKH BARABANKI 17 09150600149 BB0509224 JAI SHIV BRICK FIELD MO.PUR KHALA BARABANKI 18 09150600154 BB0008710 VISHNU KUMAR AJAY KUMAR MAIN ROAD BARABANKI 19 09150600168 BB0050354 SRI DURGA RICE AND FLOUR MILL TIWARI GANJ H Q BARABANKI 20 09150600173 BB0053854 MAZHAR AZIZ CONTRACTOR SATRIKH BARABANKI 21 09150600187 BB0051660 MANISHA ENTERPRISES FATEHPUR BARABANKI 22 09150600192 -

List of Class Wise Ulbs of Uttar Pradesh

List of Class wise ULBs of Uttar Pradesh Classification Nos. Name of Town I Class 50 Moradabad, Meerut, Ghazia bad, Aligarh, Agra, Bareilly , Lucknow , Kanpur , Jhansi, Allahabad , (100,000 & above Population) Gorakhpur & Varanasi (all Nagar Nigam) Saharanpur, Muzaffarnagar, Sambhal, Chandausi, Rampur, Amroha, Hapur, Modinagar, Loni, Bulandshahr , Hathras, Mathura, Firozabad, Etah, Badaun, Pilibhit, Shahjahanpur, Lakhimpur, Sitapur, Hardoi , Unnao, Raebareli, Farrukkhabad, Etawah, Orai, Lalitpur, Banda, Fatehpur, Faizabad, Sultanpur, Bahraich, Gonda, Basti , Deoria, Maunath Bhanjan, Ballia, Jaunpur & Mirzapur (all Nagar Palika Parishad) II Class 56 Deoband, Gangoh, Shamli, Kairana, Khatauli, Kiratpur, Chandpur, Najibabad, Bijnor, Nagina, Sherkot, (50,000 - 99,999 Population) Hasanpur, Mawana, Baraut, Muradnagar, Pilkhuwa, Dadri, Sikandrabad, Jahangirabad, Khurja, Vrindavan, Sikohabad,Tundla, Kasganj, Mainpuri, Sahaswan, Ujhani, Beheri, Faridpur, Bisalpur, Tilhar, Gola Gokarannath, Laharpur, Shahabad, Gangaghat, Kannauj, Chhibramau, Auraiya, Konch, Jalaun, Mauranipur, Rath, Mahoba, Pratapgarh, Nawabganj, Tanda, Nanpara, Balrampur, Mubarakpur, Azamgarh, Ghazipur, Mughalsarai & Bhadohi (all Nagar Palika Parishad) Obra, Renukoot & Pipri (all Nagar Panchayat) III Class 167 Nakur, Kandhla, Afzalgarh, Seohara, Dhampur, Nehtaur, Noorpur, Thakurdwara, Bilari, Bahjoi, Tanda, Bilaspur, (20,000 - 49,999 Population) Suar, Milak, Bachhraon, Dhanaura, Sardhana, Bagpat, Garmukteshwer, Anupshahar, Gulathi, Siana, Dibai, Shikarpur, Atrauli, Khair, Sikandra -

Global Hand Washing Day 2018 State Report: Uttar Pradesh

Global Hand Washing Day 2018 State Report: Uttar Pradesh Global Hand Washing Day - 15th October 2018 State Report: Uttar Pradesh Global Hand washing Day is on October 15th. The day is marked by worldwide celebrations, events, and advocacy campaigns. This year in 2018, more than 11.6 million people promoted the simple, life- saving act of hand washing with soap on Global Hand washing Day across the state. The day was founded by the Global Hand washing Partnership in 2008 to help communities, advocates, and leaders spread the word about hand washing with soap. This year’s Global Hand washing Day theme, “Clean Hands – a recipe for health,” emphasizes the linkages between hand washing and food. Hand washing is an important part of keeping food safe, preventing diseases, and helping children grow strong. Yet, hand washing is not practiced as consistently or as thoroughly as it should be. Diarrheal disease limits the body’s ability to absorb nutrition from food and is a major cause of death in low resource settings. Hand washing with soap is an effective way to prevent these losses. Global Hand washing Day raises awareness of the importance of hand washing and encourages action to promote and sustain hand washing habits. Organizations and individuals can celebrate Global Hand washing Day by planning an event, participating in a digital campaign, or simply spreading the word about the importance of hand washing. UNICEF Support: Mobilised state and district team in planning & designing of Global Hand wash Day 2018 Facilitated rally, Soap bank and other events related to GHWD at District level. -

1001 Govt.Inter College Barabanki A

PAGE:- 1 BHS&IE, UP EXAM YEAR-2021 *** PROPOSED CENTRE ALLOTMENT REPORT (UPDATED BY DISTRICT COMMITTEE) *** DIST-CD & NAME:- 63 BARABANKI DATE:- 14/02/2021 CENT-CODE & NAME CENT-STATUS CEN-REMARKS EXAM SCH-STATUS SCHOOL CODE & NAME #SCHOOL-ALLOT SEX PART GROUP 1001 GOVT.INTER COLLEGE BARABANKI A HIGH BUM 1006 D A V HR SEC SCHOOL BARABANKI 62 M HIGH CUM 1008 ANAND BHAWAN HIGH SCHOOL BARABANKI 17 F HIGH CUM 1052 RAM SEWAK YADAV SMARAK INTER COLLEGE BAREL BARABANKI 72 M HIGH CRM 1064 S S INTER COLLEGE BHANAULI BARABANKI 66 M HIGH CRM 1069 SUBHASH ADARSH I C KURAULI BARABANKI 44 M HIGH CUF 1130 S B H S SCHOOL LAKHPERA BAGH BARABANKI 16 F HIGH CUM 1134 SCHOLARS PUBLIC INTER COLLEGE BARABANKI 7 F HIGH CUF 1169 JHABER BA PATEL B V INTER COLLEGE BARABANKI 21 F HIGH CRM 1183 BHAVI BHARAT SIKSHA NIKETAN IC BARABANKI 53 M HIGH CRM 1236 RAMLAKHAN RAMDAS H S S SALEMPUR DEWA BARABANKI 19 M HIGH ARM 1262 RAJKEEYA HIGH SCHOOL BADEL BANKI BARABANKI 26 M HIGH CRM 1297 NEW VIKAS U M V MAINAHAR BARABANKI 36 M 439 INTER ARM 1009 G INTER COLLEGE BARAULI JATA BARABANKI 29 M SCIENCE INTER CUM 1079 WARIS CHILDRENS ACADEMY I C BARABANKI 33 M SCIENCE INTER CUM 1122 SRI SAI INTER COLLEGE LAKHPERABAGH BARABANKI 181 M Ist - PART SCIENCE INTER CRM 1137 JYOTI SHIKSHA NIKETAN INTER COLLEGE BHATEHATA DEWA BARABANKI 78 M SCIENCE INTER CRM 1229 RAMBHEEKH RAJRANI S S I C MALOOKPURGADIYABARABANKI 155 M SCIENCE 476 CENTRE TOTAL >>>>>> 915 1002 GOVERNMENT GIRLS INTER COLLEGE, BARABANKI A HIGH AUF 1002 GOVERNMENT GIRLS INTER COLLEGE, BARABANKI 285 F HIGH CUM 1126 PUBLIC CITY -

Communal Roosting of Egyptian Vulture Neophron Percnopterus in Uttar Pradesh, India

Published online: November 24, 2020 ISSN : 0974-9411 (Print), 2231-5209 (Online) journals.ansfoundation.org Research Article Communal roosting of Egyptian vulture Neophron percnopterus in Uttar Pradesh, India Shivangi Mishra* Biodiversity & Wildlife Conservation Lab, Department of Zoology, University of Lucknow, Article Info Lucknow-226007 (Uttar Pradesh), India https://doi.org/10.31018/ Adesh Kumar jans.v12i4.2361 Biodiversity & Wildlife Conservation Lab, Department of Zoology, University of Lucknow, Received: August 24, 2020 Lucknow-226007 (Uttar Pradesh), India Revised: November 08, 2020 ENVIS-RP, Institute for Wildlife Sciences, ONGC Center for Advanced Studies, University of Accepted: November 18, 2020 Lucknow, Lucknow-226007 (Uttar Pradesh), India Ankit Sinha Biodiversity & Wildlife Conservation Lab, Department of Zoology, University of Lucknow, Lucknow-226007 (Uttar Pradesh), India Amita Kanaujia Biodiversity & Wildlife Conservation Lab, Department of Zoology, University of Lucknow, Lucknow-226007 (Uttar Pradesh), India & ENVIS-RP, Institute for Wildlife Sciences, ONGC Center for Advanced Studies, University of Lucknow, Lucknow-226007 ( Uttar Pradesh), India *Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] How to Cite Mishra S. et al. (2020). Communal roosting of Egyptian vulture Neophron percnopterus in Uttar Pradesh, India. Journal of Applied and Natural Science, 12(4):525 - 531. https://doi.org/10.31018/jans.v12i4.2361 Abstract The behaviour of birds to settle or rest at a place at specific times of day and night is called roosting. Some birds prefer solitary roosting while others roost communally. The Communal roosting behaviour of Egyptian vulture was studied in five districts (Sambhal, Lakhimpur Kheri, Aligarh, Bareilly and Faizabad) of Uttar Pradesh, India from January 2014- December 2017. Total count was conducted at roosting sites in all the seasons (summer, winter and monsoon). -

To Read/Download Judgement

WWW.LAWTREND.IN 1 AFR Court No. 13. Judgment reserved on 22.02.2021. Judgment delivered on 18.03.2021. Criminal Appeal No. 348 of 1984. The State of U.P. vs. Kalim Ullah & Ors. Hon'ble Ramesh Sinha, J. Hon'ble Rajeev Singh, J. (Per Ramesh Sinha, J. for the Bench.) 1. This criminal appeal has been filed by the State against the judgment and order dated 19.01.1984 passed by IInd Additional District & Sessions Judge, Barabanki by which the accused-respondents have been acquitted for the offence under sections 147, 148, 302, 149 I.P.C. in S.T. No. 410 of 1982. 2. Out of five accused persons three accused-respondents, i.e., respondent nos. 1, 2 and 5, namely, Rafiullah, Naimullah, Kalimullah have died during the pendency of the appeal and the appeal on their behalf has already been ordered to be abated by Co-ordinate Bench of this Court vide order dated 19.10.2020. Hence this Court proceed to hear the appeal with respect to accused-respondent nos. 3 and 4, namely, Habibullah and Mohammad Ansar only. 3. The brief facts of the case are that an F.I.R. was lodged by one Haji Fazal-ur-rahman at police station Zaidpur, District Barabanki stating that his brother Misbah-ur-rahman was Chairman of town area Zaidpur. He was having enmity with one Dr. Habiullah and Sajid Ali with respect to election of town WWW.LAWTREND.IN 2 area and also with one Naimullah with regard to auction of a house. Rafiullah and Ansar Ahmad also belong to his party. -

Prefrenceformat Upcircle190718.Pdf

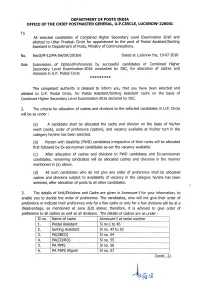

DEPARTMENT OF POSTS INDIA oFFICE OF THE CHIEF POSTMASTER GENERAL, U.P.CIRCLE, LUCKNOW-226OOL All selected candidates of Combined Higher Secondary Level Examination 2016 and allotted to Uttar Pradesh Circle for appointment to the post of Postal Assistant/Softing Assistant in Department of Posts, Ministry of Communications. No. RecttiM-12/PA-SA/DR/20L816 Dated at Lucknow the, 19-07-2018 Sub: Submission. of Option/Preferences by successful candidates of Combined Higher Secondary Level Examination-2016 conducted by SSC, for allocation of cadres and divisions in U.P. Postal Circle ********* The competent authority is pleased to inform you, that you have been selected and allotted to U.P. Postal Circle, for Postal Assistant/Sorting Assistant cadre on the basis of Combined Higher Secondary Level Examination-2016 declared by SSC. 2. The criteria for allocation of cadres and divisions to the selbcted candidates in U.P. Circle will be as under : (a) A candidate shall be allocated the cadre and division on the basis of his/her merit (rank), order of preference (option), and vacanry available at his/her turn in the category he/she has been selected. (b) Person with disability (PWD) candidates irrespective of their ranks will be allocated first followed by Ex-seruiceman candidates as per the vacancy available. (c) After allocation of cadres and divisions to PWD candidates and Ex-seruiceman candidates, remaining candidates will be allocated cadres and divisions in the manner mentioned in (a) above. (d) All such candidates who do not give any order of preference shall be allocated cadres and divisions subject to availability of vacanry in the category he/she has been selected, after allocation of posts to all other candidates.