T+ 3 "4 Table Ofcontents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MISP) of Reproductive Health Services for Internally Displaced Persons in Kathmandu and Sindhupalchowk Districts, Nepal

Women’s Refugee Commission Research. Rethink. Resolve. Evaluation of the Minimum Initial Services Package (MISP) of Reproductive Health Services for Internally Displaced Persons in Kathmandu and Sindhupalchowk Districts, Nepal Literature Review Focus Group Discussions Key Informant Interviews Health Facility Assessments May 2016 Research. Rethink. Resolve. The Women’s Refugee Commission improves the lives and protects the rights of women, children, and youth displaced by conflict and crisis. We research their needs, identify solutions, and advocate for programs and policies to strengthen their resilience and drive change in humanitarian practice. Acknowledgments This evaluation could not have been undertaken without the support of the Family Health Division (FHD), Department of Health Services (DoHS) Nepal the United Nations Population Fund Nepal (UNFPA), International Planned Parenthood Foun- dation (IPPF), and the Family Planning Association of Nepal (FPAN). We greatly appreciate the time taken by Dr. Shilu Aryal, FHD and Dr. Shilu Adhikari UNFPA in particular for supporting the Internal Review Board submission to the Nepal Research Council; hosting the Nepal RH sub-cluster MISP evaluation debriefing and support throughout the evaluation. We also deeply appreciate the time of Mr. Hari Kari UNFPA for scheduling and accompanying the evaluation team on key informant interviews; Dr. Nirmal Rimal, UNFPA for scheduling health facility assessments, and the overall support of UNFPA Country Director, Ms. Giulia Vallese. We also thank the IPPF for supporting administration and logistics for the evaluation including Ms. Nimisha Goswami and Mr. Rajrattan Lokhande, and at FPAN Mr. Subhash Shreshtha and Mr. Prabin Khadka. Thanks to Research Input and Development Action (RIDA) for conducting the focus group discussions; and FPAN for coordinating, scheduling, logistics, and overseeing recruitment of participants. -

Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal

SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics Acknowledgements The completion of both this and the earlier feasibility report follows extensive consultation with the National Planning Commission, Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS), World Food Programme (WFP), UNICEF, World Bank, and New ERA, together with members of the Statistics and Evidence for Policy, Planning and Results (SEPPR) working group from the International Development Partners Group (IDPG) and made up of people from Asian Development Bank (ADB), Department for International Development (DFID), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), UNICEF and United States Agency for International Development (USAID), WFP, and the World Bank. WFP, UNICEF and the World Bank commissioned this research. The statistical analysis has been undertaken by Professor Stephen Haslett, Systemetrics Research Associates and Institute of Fundamental Sciences, Massey University, New Zealand and Associate Prof Geoffrey Jones, Dr. Maris Isidro and Alison Sefton of the Institute of Fundamental Sciences - Statistics, Massey University, New Zealand. We gratefully acknowledge the considerable assistance provided at all stages by the Central Bureau of Statistics. Special thanks to Bikash Bista, Rudra Suwal, Dilli Raj Joshi, Devendra Karanjit, Bed Dhakal, Lok Khatri and Pushpa Raj Paudel. See Appendix E for the full list of people consulted. First published: December 2014 Design and processed by: Print Communication, 4241355 ISBN: 978-9937-3000-976 Suggested citation: Haslett, S., Jones, G., Isidro, M., and Sefton, A. (2014) Small Area Estimation of Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal, Central Bureau of Statistics, National Planning Commissions Secretariat, World Food Programme, UNICEF and World Bank, Kathmandu, Nepal, December 2014. -

The Project on Rehabilitation and Recovery from Nepal Earthquake

Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) The Project on Rehabilitation and Recovery from Nepal Earthquake Inception Report (Draft) July 2015 ORIENTAL CONSULTANTS GLOBAL CO., LTD. Pacific Consultants Co., Ltd. MOHRI, ARCHITECT & ASSOCIATES, INC CTI Engineering International Co., Ltd. PASCO CORPORATION Location Map of Project Area Nepal Kathmandu Valley Kathmandu District Kathmandu Bhaktapur District Kirtipur Bhaktapu r Madhyapur Thimi Lalitpur Kathmandu Valley district line City line Lalitpur District Village line Table of contents Location Map of Study page 1. Overview of the Project ................................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Background of the Project ........................................................................................................................................ 1 1.2 Purpose and Scope of the Project ............................................................................................................................. 1 1.3 Outputs of the Project ............................................................................................................................................... 2 1.4 Project counterpart organizations ............................................................................................................................. 3 1.5 Target area of the Project ......................................................................................................................................... -

49215-001: Earthquake Emergency Assistance Project

Environmental Assessment Document Initial Environmental Examination Loan: 3260 July 2017 Earthquake Emergency Assistance Project: Panchkhal-Melamchi Road Project Main report-I Prepared by the Government of Nepal The Environmental Assessment is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Government of Nepal Ministry of Physical Infrastructure and Transport Department of Roads Project Directorate (ADB) Earthquake Emergency Assistance Project (EEAP) (ADB LOAN No. 3260-NEP) INITIAL ENVIRONMENTAL EXAMINATION OF PANCHKHAL - MELAMCHI ROAD JUNE 2017 Prepared by MMM Group Limited Canada in association with ITECO Nepal (P) Ltd, Total Management Services Nepal and Material Test Pvt Ltd. for Department of Roads, Ministry of Physical Infrastructure and Transport for the Asian Development Bank. Earthquake Emergency Assistance Project (EEAP) ABBREVIATIONS AADT Average Annual Daily Traffic AC Asphalt Concrete ADB Asian Development Bank ADT Average Daily Traffic AP Affected People BOD Biological Oxygen Demand CBOs Community Based Organization CBS Central Bureau of Statistics CFUG Community Forest User Group CITIES Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species CO Carbon Monoxide COI Corridor of Impact DBST Double Bituminous Surface Treatment DDC District Development Committee DFID Department for International Development, UK DG Diesel Generating DHM Department of Hydrology and Metrology DNPWC Department of National -

Annual Progress Report 2018/19

ANNUAL PROGRESS REPORT 2018/19 Campaign for Human Rights and Social Transformation (CAHURAST), Nepal 1 CONTENTS 1. Introduction – About CAHURAST 3 2. Projects in 2018/19 4 3. Highlights and Achievements of 2018/19 9 4. Monitoring in Glance 14 5. Our priorities for 2019/20 15 6. CAHURAST’s publication 2018/19 16 7. Human Resources in 2018/19 18 2 INTEGRITY About CAHURAST TEAM WORK CAHURAST is one of the leading human INNOVATION AND CREATIVITY rights NGO established on 29 th Kartik, 2063 with the motto to work for human rights and to protect all the rights with the special focus on ORGANIZATIONAL EQUITY AND SOCIAL JUSTICE Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. It has VALUES AND GUIDING consultative status with the Economic and PRINCIPLES Social Council of the United Nations CARE FOR ENVIRONMENT (ECOSOC). In 2018/19, our work was guided by our strategic CAHURAST’s priority areas plab for 2017-2021 Priority Area I: Democracy, Humab rights abd Visiob Peace A holistically transformed Nepali society where Goal: To contribute in promoting ESC rights, mitigating ethnic and social conflicts and promoting people live in peace and harmony with each other peace in Nepal and enjoying human rights and peace Priority Area II : Research, Advocacy abd Mission Kbowledge Mabagemebt • Facilitating empowerment process of the poor Goal: To provide resources and knowledge on the and marginalized communities for empowering issues of ESC rights and influence p olicy for themselves through education, empowerment promoting ESC rights of marginalized groups and engagement -

2015 Nepal Earthquake Response Project Putting Older People First

2015 Nepal Earthquake Response Project PUTTING OLDER PEOPLE FIRST A Special newsletter produced by HelpAge to mark the first four months of the April 2015 Earthquake CONTENTS Message from the Regional Director Editorial 1. HelpAge International in Nepal - 2015 Nepal Earthquake 1-4 Response Project (i) Unconditional Cash Transfers (UCTs) (ii) Health Interventions (iii) Inclusion- Protection Programme 2. Confidence Re-Born 5 3. Reflections from the Field 6 4. Humanitarian stakeholders working for Older People and 7-8 Persons with Disabilities in earthquake-affected districts 5. A Special Appeal to Humanitarian Agencies 9-11 Message from the Regional Director It is my great pleasure to contribute a few words to this HelpAge International Nepal e-newsletter being published to mark the four-month anniversary of the earthquake of 25 April, 2015, focusing on ‘Putting Older People First in a Humanitarian Response’. Of the eight million people in the 14 most earthquake-affected districts1, an estimated 650,000 are Older People over 60 years of age2, and are among the most at risk population in immediate need of humanitarian assistance. When factoring-in long-standing social, cultural and gender inequalities, the level of vulnerability is even higher among the 163,043 earthquake-affected older women3. In response to the earthquake, HelpAge, in collaboration with the government and in partnership with local NGOs, is implementing cash transfers, transitional shelter, health and inclusion-protection activities targeting affected Older People and their families. Furthermore, an Age and Disability Task Force-Nepal (ADTF-N)4 has been formed to highlight the specific needs and vulnerabilities of Older People and Persons with Disabilities and to put them at the centre of the earthquake recovery, rehabilitation and reconstruction efforts. -

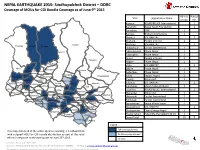

NEPAL EARTHQUAKE 2015: Sindhupalchok District – DDRC Coverage of Mous for CGI Bundle Coverage As of June 9Th 2015

NEPAL EARTHQUAKE 2015: Sindhupalchok District – DDRC Coverage of MOUs for CGI Bundle Coverage as of June 9th 2015 All HHs Partial VDC Organization Name of VDC HH Atarpur ASSAB/RELIEF International 1 Baramchi Nepal Youth Foundation 1 Barhabise IOM 1 Baruwa Global Communities 1 Bhimtar UN-HABITAT 1 Bhotang People in Need 1 Gumba Bhotsipa UN-HABITAT 1 Helambu Baruwa Bhotang Duwachaur Caritas Switzerland 1 Golche Fulpingdanda Phase Nepal 1 Fulpingkot Phase Nepal 1 Gunsa People in Need 1 Tatopani Hagam Phase Nepal 1 Thapalkot Irkhu UN-HABITAT 1 Ichok Kiul Ghunsakot Jalbire Phase Nepal 1 Ghuyang (Thanpalchap) Listokot Banskharka Kadambas Phase Nepal 1 Pangtang Palchok Mahangkal Bhotenamlang Phulpingkatti Kalika Impact Nepal 1 Kiwool Action Aid 1 Dubachaur Lagarche Baramchae Dhuyang Talamarang Kubinde UN-HABITAT 1 Thakani Jyamire Selang Hagam Marming Melamchi Sinpal Kavre Gati Kunchowk Micah Network Nepal 1 Sindhukot Syaule Jalbire Haibung ShikharpurNawalpur Batase Lisankhu ASSAB/RELIEF International 1 Bansbari Maneswar Barhabise Karthali Bhotechaur Phulpingkot Mahankal Action Aid 1 Bandegaun KunchokPipaldanda Ramche Ghorthali ChautaraKubhinde Mangkha Melamchi Caritas Switzerland 1 PhataksilaSipapokharae Gunsakun Sanusirubari Phulchodanda Tekanpur Chokati Palchowk Caritas Switzerland 1 Irkhu Pangretar BhimtarBhotsipa Piskar Sanosirubari Peace Winds Japan 1 Kadambas Thumpakhar Thulo Sirubari Pedku Yamuna Danda Tauthali Sipapokhare UN-HABITAT 1 SunkhaniThulo Pakhar Thulopakhar Clean Energy Nepal 1 Sangachok Kalika Jethal Thokarpa Attarpur Thulosirubari Help-hilfe the Selbsthilfe CV 1 Grand Total 19 8 Lisangkhu Thulo Dhading Legend Full coverage planned This map details all of the active agencies working in Sindhupalchok with a signed MOU for CGI bundle distribution as part of the relief Partial coverage planned th efforts in response to the earthquake on April 25 2015. -

Melamchi Municipality, Nepal Situation Analysis for Green Municipal Development

Melamchi Municipality, Nepal Situation Analysis for Green Municipal Development May 2018 1 a Global Green Growth Institute May 2018 Global Green Growth Institute Jeongdong Building 19F 21-15 Jeongdong-gil Jung-gu, Seoul 04518 Republic of Korea Recommended citation: GGGI (2018). Melamchi Municipality, Nepal: Situation Analysis for Green Municipal Development. Seoul: Global Green Growth Institute. This report is one of a set of seven situation analyses of the Nepalese municipalities of Belkotgadhi, Dakshinkali, Mahalaxmi, Melamchi, Namobuddha, Palungtar and Thaha. All seven reports are available at www.gggi.org/country/nepal/ The Global Green Growth Institute does not make any warranty, either express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or any third party’s use or the results of such use of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed of the information contained herein or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. The views and opinions of the authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the Global Green Growth Institute. Design and printing by Pentagram, Nepal. Cover photo of Melamchi by Robic Upadhayay. Melamchi Municipality, Nepal Situation Analysis for Green Municipal Development May 2018 Acknowledgements This situational analysis and accompanying report were who provided detailed technical support during the prepared by the Global Green Growth Institute (GGGI) in preparation of the seven reports. GGGI would also Nepal under its Green Municipal Development Program. like to thank the municipal leaders, in particular the GGGI and the program team would like to express their mayors and chief administrative officers (CAOs) of gratitude to the Ministry of Forests and Environment each of the municipalities of Belkotgadhi, Dakshinkali, (MoFE), and in particular to Dr. -

Assessment of Water Resources Management & Freshwater

Philanthropy Support Services, Inc. Assessment Bringing skills, experience, contacts and passion to the worlds of global philanthropy and international development of Water Resources Management & Freshwater Biodiversity in Nepal Final Report George F. Taylor II, Mark R. Weinhold, Susan B. Adams, Nawa Raj Khatiwada, Tara Nidhi Bhattarai and Sona Shakya Prepared for USAID/Nepal by: United States Forest Service International Programs Office, Philanthropy Support Services (PSS) Inc. and Nepal Development Research Institute (NDRI) September 15, 2014 Disclaimer: The views expressed in this document are the views of the authors. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government ! ! ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Assessment Team wishes to acknowledge the support of: ! The dynamic USAID Environment Team and its supporters across the USAID Mission and beyond, particularly Bronwyn Llewellyn and Shanker Khagi who provided exemplary support to all phases of the Assessment process. ! USAID/Nepal senior staff, including Director Beth Dunford and SEED Acting Director Don Clark for allowing Bronwyn, Shanker and SEED Summer Intern Madeline Carwile to accompany the Assessment Team on its full five day field trip. Seeing what we saw together, and having a chance to discuss it as we travelled from site to site and during morning and evening meals, provided a very important shared foundation for the Assessment exercise. ! NDRI, including the proactive support of Executive Director Jaya Gurung and the superb logistical support from Sona Shakya. ! The United States Forest Service International Programs Office staff, particularly Sasha Gottlieb, Cynthia Mackie and David Carlisle, without whom none of this would have happened. -

N E P a L Kathmandu ! CEN\TRAL

86°0'0"E o LANGTANG Helicopter LZ Highway Int. Boundary Accessibility Source Primary road District bound. Within walking 5 distance from road L !f UNHAS Sec. road VDC boundary 1 Within walking !f USMC A 0 distance from 4X4 road R a s u w a f 2 ! NPL Military No road access P e Data Sources: WFP, LC, UNGIWG, Survey Department of Nepal, Date Created: 04 June 2015 Prepared by: LogCluster GeoNames, © OpenStreetMap contributors, E Assessments, UNHAS, USMC, NPL Military, ICIMOD n Contact: [email protected] Map Reference: The boundaries and names and the designations used on this map do u Website: www.logcluster.org NPL_OP_sindupalchokAccessMap_A3L not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. N J - FAR-WESTERN C H I N A MID-WESTERN p Helambu WESTERN a Pop: 2748 N E P A L Kathmandu ! CEN\TRAL M I N D I A EASTERN Gumba s Pop: s Baruwa Bhotang 3677 e Pop: 1962 Pop: 2767 0 2.5 5 10 c Melamchi Ghyang Tembathau c Tembathau Max Heli: Mi-8 f Kilometers f Sunchaur Max Heli: ? f! ± ! A ! f Tarkeghang ! Golche f N Tarkeygyang f f ! " 0 k Ghangkharka ! ' ! 0 f ° Max Heli: 8 ! 2 o Mi-8 Simbakharka h f Tatopani Golche ! G318 c f Pop: 7259 N u w a k o t Bothang Pop: 3870 ! Kamsking l Gumba Beilgaur f 3 f f! Gumba f 0 a !! ! H Singarche Baouara Bhotang Max Heli: ? !f Kodari p ! !f Max Heli:T ?hap!alkot NanLkihdairkLaidrLi arke Pop: 2824 f u Max Heli: ? !f ! f Bolde Kutumsang Rewar ! C H I N A h ! Ichok Kiul Max Heli: Mi-8 f Sanjagaun f Pop: 3161 Chibihang ! f Lissti Rasithau Pop: 5773 f ! f d Max Heli: ? ! f ! Ghunsakot f ! ! Pop: 2038 -

Community Resilience Capacity

COMMUNITY RESILIENCE CAPACITY A STUDY ON NEPAL’S 2015 EARTHQUAKES AND AFTERMATH Central Department of Anthropology Tribhuvan University Kirtipur, Kathmandu, Nepal COMMUNITY RESILIENCE CAPACITY B A STUDY ON NEPAL’S 2015 EARTHQUAKES AND AFTERMATH COMMUNITY RESILIENCE CAPACITY A STUDY ON NEPAL’S 2015 EARTHQUAKES AND AFTERMATH Mukta S. Tamang In collaboration with Dhanendra V. Shakya, Meeta S. Pradhan, Yogendra B. Gurung, Balkrishna Mabuhang SOSIN Research Team PROJECT COORDINATOR Dr. Dambar Chemjong RESEARCH DIRECTOR Dr. Mukta S. Tamang TEAM LEADERS Dr. Yogendra B Gurung Dr. Binod Pokharel Dr. Meeta S. Pradhan Dr. Mukta S. Tamang TEAM MEMBERS Dr. Dhanendra V. Shakya Dr. Meeta S. Pradhan Dr. Yogendra B. Gurung Mr. Balkrishna Mabuhang Mr. Mohan Khajum ADVISORS/REVIEWERS Dr. Manju Thapa Tuladhar Mr. Prakash Gnyawali I COMMUNITY RESILIENCE CAPACITY A Study on Nepal’s 2015 Earthquakes and Aftermath Copyright @ 2020 Central Department of Anthropology Tribhuvan University This study is made possible by the support of the American People through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents of this report are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government or Tribhuvan University. Published by Central Department of Anthropology (CDA) Tribhuvan University (TU), Kirtipur, Kathmandu, Nepal Tel: + 977- 01-4334832 Email: [email protected] Website: www.anthropologytu.edu.np First Published: October 2020 300 Copies Cataloguing in Publication Data Tamang, Mukta S. Community resilience capacity: a study on Nepal’s 2015 earthquakes and aftermath/ Mukta S.Tamang …[ et al. ] Kirtipur : Central Department of Anthropology, Tribhuvan University, 2020. -

RS Sindhupalchwok.Pdf

g]kfn ;/sf/ ;+3Lo dfldnf tyf :yfgLo ljsf; dGqfno s]Gb|Lo cfof]hgf sfof{Gjog OsfO{ e"sDkLo cfjf; k'glg{df{0f cfof]hgf Hjfun, nlntk'/ l;Gw'kfNrf]s k'gM;j]{If0f ug'{kg]{ nfeu|fxL ljj/0f . S.N G_ID RV/RS Grievant Name District VDC/MUN (P) Ward(P) Tole GP/NP WARD Slip No Remarks 1 249093 RS Surya Bdr. Shrestha Sindhupalchowk Attarpur 1 Lisankhu Pakhar 4 401862 2 249218 RS Hom Bdr.Joshi Sindhupalchowk Attarpur 9 Lisankhu Pakhar 4 3 253782 RS Shiva Lal Shrestha Sindhupalchowk Badegaun 1 Indrawati 6 360056 4 253781 RS Datte Shrestha Sindhupalchowk Badegaun 1 Indrawati 6 5 253784 RS Raju Shahi Thakuri Sindhupalchowk Badegaun 1 Indrawati 6 6 253783 RS Harisharan Shahi Sindhupalchowk Badegaun 1 Indrawati 6 7 253687 RS Ram Babu Koirala Sindhupalchowk Badegaun 2 Indrawati 6 8 253806 RS Dipak Shrestha Sindhupalchowk Badegaun 3 Indrawati 6 9 253818 RS Govinda Prasad Poudel Sindhupalchowk Badegaun 3 Indrawati 6 10 253681 RS Dipak Raj Bhattarai Sindhupalchowk Badegaun 3 Indrawati 6 11 253808 RS Radhika Devi Neupane Sindhupalchowk Badegaun 3 Indrawati 6 12 253683 RS Madhab Bahadur Khatri Sindhupalchowk Badegaun 3 Indrawati 6 13 253820 RS Jagendra Prasad Bhetuwal Sindhupalchowk Badegaun 3 Indrawati 6 14 253706 RS Padam Hari Sanjel Sindhupalchowk Badegaun 3 Indrawati 6 15 253804 RS Lila Bikram Thapa Sindhupalchowk Badegaun 3 Indrawati 6 16 253676 RS Purna Prasad Bhattarai Sindhupalchowk Badegaun 3 Indrawati 6 17 253689 RS Bhairab Prasad Dahal Sindhupalchowk Badegaun 3 Indrawati 6 18 253682 RS Jit Bahadur B.K. Sindhupalchowk Badegaun 3 Indrawati 6 19 253813