R E V I E W Issue 7W 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2021 Anthology

CREATING SPACES 2021 A collection of the winning writings of the 2021 writing competition entitled Creating Spaces: Giving Voice to the Youth of Minnesota Cover Art: Ethan & Kitty Digital Photography by Sirrina Martinez, SMSU alumna Cover Layout: Marcy Olson Assistant Director of Communications & Marketing Southwest Minnesota State University COPYRIGHT © 2021 Creating Spaces: Giving Voice to the Youth of Minnesota is a joint project of Southwest Minnesota State University’s Creative Writing Program and SWWC Service Cooperative. Copyright reverts to authors upon publication. Note to Readers: Some of the works in Creating Spaces may not be appropriate for a younger reading audience. CONTENTS GRADES 3 & 4 Poetry Emma Fosso The Snow on the Trees 11 Norah Siebert A Scribble 12 Teo Winger Juggling 13 Fiction Brekyn Klarenbeek Katy the Super Horse 17 Ryker Gehrke The Journey of Color 20 Penni Moore Friends Forever 35 GRADES 5 & 6 Poetry Royalle Siedschlag Night to Day 39 Addy Dierks When the Sun Hides 40 Madison Gehrke Always a Kid 41 Fiction Lindsey Setrum The Secret Trail 45 Lindsey Setrum The Journey of the Wild 47 Ava Lepp A Change of Heart 52 Nonfiction Addy Dierks Thee Day 59 Brystol Teune My Washington, DC Trip 61 Alexander Betz My Last Week Fishing with my Great Grandpa 65 GRADES 7 & 8 Poetry Brennen Thooft Hoot 69 Kelsey Hinkeldey Discombobulating 70 Madeline Prentice Six-Word Story 71 Fiction Evie Simpson A Dozen Roses 75 Keira DeBoer Life before Death 85 Claire Safranski Asylum 92 Nonfiction Mazzi Moore One Moment Can Pave Your Future -

HEADLINE NEWS • 3/23/07 • PAGE 2 of 2

DISTAFF BC DRAWS 7 HEADLINE p. 2 NEWS For information about TDN, DELIVERED EACH NIGHT BY FAX AND FREE BY E-MAIL TO SUBSCRIBERS OF call 732-747-8060. www.thoroughbreddailynews.com FRIDAY, MARCH 23, 2007 BAILEY & NBC RECEIVE SPORTS EMMY NOMS ‘GOLD’ READY FOR FLORIDA DERBY Former jockey and ESPN horse racing analyst Jerry Adore the Gold (Formal Gold), last seen finishing a Bailey as well as NBC each received nominations for the good fourth behind Scat Daddy (Johannesburg) in the 28th annual Sports Emmy Mar. 3 GII Fountain of Youth S., Awards, it was announced yes- will take on that foe again in the terday. Bailey was nominated in Mar. 31 GI Florida Derby. AEv- the category of Outstanding erything is good,@ trainer Michael Sports Personality-Sports Event Gorham said. AWe just need to Analyst, while NBC was nomi- improve a length. Hopefully that nated for its coverage of the race helped him. He keeps get- ting a little fitter and that race 2006 GI Preakness S. in the Out- Adore The Gold helped. He's training good and standing Live Sports Special cat- Equi-Photo egory. AI=m flat- coming into tered to be this race really good. Having a race at nominated,@ “I look forward to a mile-and-an-eighth already should help as well.@ Adore the Gold, winner said Bailey. AIt=s receiving the TDN a tribute to the of the 1 1/16-mile Dover S. at Dela- Jerry Bailey every night. It has ware as a juvenile, notched Horsephotos people I work become the gold with, particu- Gulfstream=s 6 1/2-furlong GII Swale standard for learning larly Randy Moss, Chris Fowler, Kenny S. -

Futurism-Anthology.Pdf

FUTURISM FUTURISM AN ANTHOLOGY Edited by Lawrence Rainey Christine Poggi Laura Wittman Yale University Press New Haven & London Disclaimer: Some images in the printed version of this book are not available for inclusion in the eBook. Published with assistance from the Kingsley Trust Association Publication Fund established by the Scroll and Key Society of Yale College. Frontispiece on page ii is a detail of fig. 35. Copyright © 2009 by Yale University. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers. Designed by Nancy Ovedovitz and set in Scala type by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Printed in the United States of America by Sheridan Books. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Futurism : an anthology / edited by Lawrence Rainey, Christine Poggi, and Laura Wittman. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-300-08875-5 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Futurism (Art) 2. Futurism (Literary movement) 3. Arts, Modern—20th century. I. Rainey, Lawrence S. II. Poggi, Christine, 1953– III. Wittman, Laura. NX456.5.F8F87 2009 700'.4114—dc22 2009007811 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48–1992 (Permanence of Paper). 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 CONTENTS Acknowledgments xiii Introduction: F. T. Marinetti and the Development of Futurism Lawrence Rainey 1 Part One Manifestos and Theoretical Writings Introduction to Part One Lawrence Rainey 43 The Founding and Manifesto of Futurism (1909) F. -

Turf-Times Der Deutsche Newsletter Für Vollblutzucht & Rennsport Mit Dem Galopp-Portal Unter

Ausgabe 269 • 36 Seiten Freitag, 14. Juni 2013 powered by TURF-TIMES www.bbag-sales.de Der deutsche Newsletter für Vollblutzucht & Rennsport mit dem Galopp-Portal unter www.turf-times.de AUFGALOPP Probably läuft im Derby „Next stop German Derby“ lautete die Nachricht, die Die Bilder, die wir in den vergangenen Tagen in uns Trainer Rune Haugen am Mittwoch aus Norwe- den Medien gesehen haben, werden so schnell nicht gen bezüglich des von ihm betreuten Probably (Da- vergessen werden. Überschwemmte Landschaften, nehill Dancer) übermittelte. Damit wird das Sparda Menschen, die ihr Hab und Gut verloren haben, die 144. Deutsche Derby in jedem Fall international. Im vor den Trümmern ihrer Existenz stehen. Der Ga- vergangenen Jahr wurde der Hengst noch von David lopprennsport hat in der tagesaktuellen Berichter- Wachman für die Besitzergemeinschaft Tabor/Mag- stattung naturgemäß überhaupt keine Rolle gespielt, nier/Smith trainiert, gewann die Railway Stakes (Gr. auch wenn es zwei Rennbahnen betroffen hat, Halle II), war u.a. Dritter in den Beresford Stakes (Gr. II) und Magdeburg, nicht zum ersten Mal. Ausgerech- und Vierter in den National Stakes (Gr. I) in aller- net. Bahnen, die ohnehin nicht gerade mit Reichtum dings stets kleinen Feldern, über Winter wurde er an gesegnet sind, deren Überleben in der Vergangenheit den Stall NOR verkauft. Beim Jahresdebut belegte des Öfteren am seidenen Faden gehangen hat, denen er sieben Längen hinter Nicolosio (Peintre Celebre) schon mehrfach die Existenzberechtigung abgespro- Rang zwei im Derby-Trial in Hannover. Am Dienstag chen wurde, weil sie wirtschaftlich angeblich nicht gewann er im schwedischen Jägersro ein übersichtlich tragfähig sind. Doch wo in diesen Tagen trotzdem besetztes 2400-m-Rennen als 11:10-Favorit mit 22 Menschen arbeiten und alles erdenklich mögliche Längen Vorsprung. -

|What to Expect from L'elisir D'amore

| WHAT TO EXPECT FROM L’ELISIR D’AMORE AN ANCIENT LEGEND, A POTION OF QUESTIONABLE ORIGIN, AND THE WORK: a single tear: sometimes that’s all you need to live happily ever after. When L’ELISIR D’AMORE Gaetano Donizetti and Felice Romani—among the most famous Italian An opera in two acts, sung in Italian composers and librettists of their day, respectively—joined forces in 1832 Music by Gaetano Donizetti to adapt a French comic opera for the Italian stage, the result was nothing Libretto by Felice Romani short of magical. An effervescent mixture of tender young love, unforget- Based on the opera Le Philtre table characters, and some of the most delightful music ever written, L’Eli s ir (The Potion) by Eugène Scribe and d’Amore (The Elixir of Love) quickly became the most popular opera in Italy. Daniel-François-Esprit Auber Donizetti’s comic masterpiece arrived at the Metropolitan Opera in 1904, First performed May 12, 1832, at the and many of the world’s most famous musicians have since brought the opera Teatro alla Cannobiana, Milan, Italy to life on the Met’s stage. Today, Bartlett Sher’s vibrant production conjures the rustic Italian countryside within the opulence of the opera house, while PRODUCTION Catherine Zuber’s colorful costumes add a dash of zesty wit. Toss in a feisty Domingo Hindoyan, Conductor female lead, an earnest and lovesick young man, a military braggart, and an Bartlett Sher, Production ebullient charlatan, and the result is a delectable concoction of plot twists, Michael Yeargan, Set Designer sparkling humor, and exhilarating music that will make you laugh, cheer, Catherine Zuber, Costume Designer and maybe even fall in love. -

Tdn America Today the Week in Review: Zed Run Spending Spree Goes on T

MONDAY, MAY 24, 2021 BREEDING & SELLING THE TRAINER LIZ MERRYMAN HAS HIGH HOPES FOR HOMEBRED FILLY by Katie Ritz MILLION-DOLLAR RACEHORSE It=s a rare feat to get to the winner=s circle on one of the THAT DOESN'T EXIST biggest weekends in racing with a horse bred, owned and trained by the same connection, but Elizabeth Merryman did just that when her speedy filly Caravel (Mizzen Mast) gave a gutsy performance at Pimlico to take The Very One S. by a nose on Preakness weekend. Many would consider the juggling act between the foaling barn and the training center to be an impossibility, but Liz Merryman says, for her, it=s the best way to produce a racehorse. AI love working with a horse that has no mystery to what happened before I got them,@ she said. AYou know everything about them, you know why they do what they do and it=s really rewarding. It=s my favorite way to train a horse.@ Did last Friday=s victory mark Caravel as the most successful homebred Merryman has brought up? ADefinitely,@ the Fair Hill-based trainer said. Cont. p5 Zed Run photo IN TDN EUROPE TODAY The Week in Review, by T.D. Thornton BALLYDOYLE EXACTA IN IRISH 1000 GUINEAS There's an adage in poker playing that says if you take a look Empress Josephine (Ire) (Galileo {Ire}) nosed out Aidan O’Brien around the card table and can't tell who the sucker in the game stablemate Joan of Arc (Ire) (Galileo {Ire}) in the G1 Tattersalls Irish is, it's you. -

Billesdon Brook in Guineas Shock

MONDAY, 7 MAY, 2018 that her success in the Prestige at Goodwood in late August was BILLESDON BROOK IN her big moment. Along the way, she had come off second best to the smart fillies Madeline (Ire) (Kodiac {GB}) and Nyaleti (Ire) GUINEAS SHOCK (Arch) at Goodwood and Salisbury but on the Polytrack she showed what she could do on a sound surface when registering a six-length success in a novice contest at Kempton in July. Third in the Listed Star S. at Sandown before capturing a nursery at Glorious Goodwood over the same trip as the Prestige, she went from there to the G2 May Hill S. at Doncaster in September but was only fifth to Laurens on good-to-soft ground. Still some way off looking a Guineas heroine when fourth on her comeback behind Soliloquy (GB) (Dubawi {Ire}) in the G3 Nell Gwyn S. here Apr. 18, she even occupied third rank of her stable=s contenders which included her relative and fellow Stowell Hill homebred Anna Nerium (GB) (Dubawi {Ire}). Cont. p2 IN TDN AMERICA TODAY Billesdon Brook wins the 1000 Guineas at odds of 66-1 | Racing Post ‘PHENOMENAL’ JUSTIFY EYES MIDDLE JEWEL GI Kentucky Derby hero Justify (Scat Daddy) emerged from his authoritative victory in the slop with excellent energy Sunday morning and trainer Bob Baffert indicated the colt will be Not even considered the number one filly from Richard pointed to a start in the May 19 GI Preakness S. at Pimlico. Click Hannon=s stable, last year=s G3 Prestige S. -

HOWARD GOODALL CHORAL MUSIC AVAILABLE from FABER MUSIC LTD BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES CONTENTS Howard Goodall Is One of Britain’S Most Distinguished and Versatile Composers

for CONCERT · STAGE · WORLD · DANCE HOWARD GOODALL CHORAL MUSIC AVAILABLE FROM FABER MUSIC LTD BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES CONTENTS Howard Goodall is one of Britain’s most distinguished and versatile composers. Almost everyone knows at least one of Howard's popular TV themes for __LIST OF WORKS: Blackadder, Mr Bean, Red Dwarf, The Catherine Tate Show, Q.I. or The Vicar of Dibley. Film scores Chorus & Orchestra __3 include the BAFTA-nominated The Gathering Storm, Bean: The Ultimate Disaster __4 Upper Voices Movie, Bernard and the Genie, Blackadder Back & Forth and Mr Bean’s Holiday. __8 Mixed Voices In the theatre his many musicals, from The Hired Man (1984) to Two Cities (2006) __10 Male Voices have been performed throughout the English-speaking world, including London’s West End and Off-Broadway, and won many international awards, including Ivor Novello __10 As Presenter and TMA Awards for Best Musical. In 2009 his A Winter’s Tale will be seen around the __10 Selected Discography country performed by Youth Music Theatre: UK, The Dreaming will be produced by National Youth Music Theatre, and in 2010 Love Story will have its professional première. __11 Reviews He is a prodigious writer of choral music, his settings of Psalm 23 and Love Divine are CONTACTS amongst the most performed of all sacred music, his works have been commissioned to mark several national ceremonies and memorials, and he has contributed songs to USA/CANADA: several platinum-selling CDs. Autumn 2008 saw the début UK tour of his (Sales/Marketing) Eternal Faber Music Inc Light: A Requiem by the Rambert Dance Company, a choral-orchestral ballet & concert 16320 Roscoe Boulevard work commissioned by London Musici, simultaneously released on an EMI Classics CD Van Nuys CA 91406 featuring the Choir of Christ Church Cathedral Oxford, Alfie Boe and Natasha Marsh, USA conducted by Stephen Darlington, for which Howard won the 2009 Classical Brit Tel:+1818 891 5999 ex.237 [email protected] Award for ‘Composer of the Year’. -

Palmarès Cecil

Sir Henry Richard-Amherst CECIL Victoires de Groupes 1 (les vainqueurs) Prix Hippodrome Pays Année Cheval Jockey Propriétaire Sussex Stakes Goodwood GB 1997 Ali-Royal Kieren-Francis Fallon Greenbay Stables Ltd Moulin de Longchamp Longchamp FRA 1992 All At Sea Patrick Eddery Khalid Abdullah 2e Oaks Epsom GB 1992 All At Sea Patrick Eddery Khalid Abdullah Irish Oaks Curragh IRE 1989 Alydaress Michael J. Kinane Cheik Ahmed Al Maktoum Trophy (Observer Gold Cup) (2 ans) Doncaster GB 1969 Approval Duncan Keith Sir Humphrey de Trafford Gold Cup Royal Ascot GB 1982 Ardross Lester Piggott C.A.B. St George 2e Arc de Triomphe Longchamp FRA 1982 Ardross Lester Piggott C.A.B. St George Gold Cup Royal Ascot GB 1981 Ardross Lester Piggott C.A.B. St George Royal-Oak Longchamp FRA 1981 Ardross (5 ans) Lester Piggott C.A.B. St George Trophy (Racing Post) (2 ans) Doncaster GB 1992 Armiger Patrick Eddery Khalid Abdullah Trophy (Racing Post) (2 ans) Doncaster GB 1989 Be My Chief Steve Cauthen Peter Burrell Grand Prix de Paris Longchamp FRA 2000 Beat Hollow Thomas-Richard Quinn Khalid Abdullah 3e Derby St. Epsom GB 2000 Beat Hollow Thomas-Richard Quinn Khalid Abdullah King George VI & Queen Elizabeth St. Ascot GB 1990 Belmez Michael J. Kinane Cheik Moh. Al Maktoum 3e Irish Derby St. Curragh IRE 1990 Belmez Steve Cauthen Cheik Moh. Al Maktoum Lockinge Stakes (Gr.II) Newbury GB 1981 Belmont Bay Lester Piggott Daniel Wildenstein Sussex Stakes Goodwood GB 1975 Bolkonski Gianfranco Dettori Carlo d'Alessio St James's Palace St. (Gr.II) Royal Ascot GB 1975 Bolkonski Gianfranco Dettori Carlo d'Alessio 2000 Guinées Newmarket GB 1975 Bolkonski Gianfranco Dettori Carlo d'Alessio 2e Irish Derby St. -

2008 File1lined.Vp

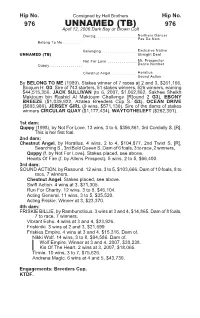

Hip No. Consigned by Hall Brothers Hip No. 976 UNNAMED (TB) 976 April 12, 2006 Dark Bay or Brown Colt Danzig .....................Northern Dancer Pas De Nom Belong To Me .......... Belonging ..................Exclusive Native UNNAMED (TB) Straight Deal Not For Love ...............Mr. Prospector Quppy................. Dance Number Chestnut Angel .............Horatius Sound Action By BELONG TO ME (1989). Stakes winner of 7 races at 2 and 3, $261,166, Boojum H. G3. Sire of 743 starters, 51 stakes winners, 526 winners, earning $44,515,356, JACK SULLIVAN (to 6, 2007, $1,062,862, Sakhee Sheikh Maktoum bin Rashid Al Maktoum Challenge [R]ound 2 G3), EBONY BREEZE ($1,039,922, Azalea Breeders Cup S. G3), OCEAN DRIVE ($803,986), JERSEY GIRL (9 wins, $571,136). Sire of the dams of stakes winners CIRCULAR QUAY ($1,177,434), WAYTOTHELEFT ($262,391). 1st dam: Quppy (1998), by Not For Love. 13 wins, 3 to 6, $356,861, 3rd Cordially S. [R]. This is her first foal. 2nd dam: Chestnut Angel, by Horatius. 4 wins, 2 to 4, $104,877, 2nd Twixt S. [R], Searching S., 3rd Bold Queen S. Dam of 6 foals, 3 to race, 2 winners, Quppy (f. by Not For Love). Stakes placed, see above. Hearts Of Fire (f. by Allens Prospect). 5 wins, 2 to 5, $66,400. 3rd dam: SOUND ACTION, by Resound. 12 wins, 3 to 5, $103,666. Dam of 10 foals, 8 to race, 7 winners, Chestnut Angel. Stakes placed, see above. Swift Action. 4 wins at 3, $71,305. Run For Charity. 12 wins, 3 to 8, $46,104. -

On Conducting by Richard Wagner (Translated by Edward Dannreuther)

On Conducting by Richard Wagner (translated by Edward Dannreuther) TABLE OF CONTENTS POEM FRONTISPIECE TRANSLATOR'S NOTE ON CONDUCTING APPENDIX A APPENDIX B APPENDIX C APPENDIX D POEM FRONTISPIECE (1869). MOTTO NACH GOETHE: "Fliegenschnauz' und Muckennas' Mit euren Anverwandten, Frosch im Laub und Grill' im Gras, Ihr seid mir Musikanten!" * * * * * * * * "Flysnout and Midgenose, With all your kindred, too, Treefrog and Meadow-grig. True musicians, YOU!" (After GOETHE). [The lines travestied are taken from "Oberon und Titanias goldene Hochzeit." Intermezzo, Walpurgisnacht.--Faust I.] TRANSLATOR'S NOTE. Wagner's Ueber das Dirigiren was published simultaneously in the "Neue Zeitschrift fur Musik" and the "New-Yorker Musik-zeitung," 1869. It was immediately issued in book form, Leipzig, 1869, and is now incorporated in the author's collected writings, Vol. VIII. p. 325-410. ("Gesammelte Schriften und Dichtungen von Richard Wagner," ten volumes, Leipzig, 1871-1883.) For various reasons, chiefly personal, the book met with much opposition in Germany, but it was extensively read, and has done a great deal of good. It is unique in the literature of music: a treatise on style in the execution of classical music, written by a great practical master of the grand style. Certain asperities which pervade it from beginning to end could not well be omitted in the translation; care has, however, been taken not to exaggerate them. To elucidate some points in the text sundry extracts from other writings of Wagner have been appended. The footnotes, throughout, are the translator's. ON CONDUCTING The following pages are intended to form a record of my experience in a department of music which has hitherto been left to professional routine and amateur criticism. -

Ptacy B Allada O Eugeniuszu Ludzie Dokumentalna Rudniku I

Ptacy i ludzie Ballada Ballada dokumentalna o Eugeniuszu Rudniku Bolesław Błaszczyk i inni Rudniku Ballada o Eugeniuszu dokumentalna Ptacy Ptacy i ludzie Bolesław Błaszczyk i inni Ptacy i ludzie Ballada Ballada dokumentalna o Eugeniuszu Rudniku Warszawa-Łódź 2020 BIBLIOTEKA SEPR Seria pod redakcją Michała Mendyka i Agnieszki Pindery Ptacy i ludzie. Ballada dokumentalna o Eugeniuszu Rudniku Redakcja: Agnieszka Hatowska, Małgorzata Poździk Korekta: Agnieszka Hatowska Współpraca: Katarzyna Radomska Projekt graficzny, skład i łamanie: Magda Burdzyńska Fotografia na okładce: Andrzej Zborski © Muzeum Sztuki Nowoczesnej w Warszawie © Autorzy i autorki © Fundacja Automatophone (Bôłt Publishing) © Muzeum Sztuki w Łodzi © Wydawnictwo Krytyki Politycznej Dofinansowano ze środków Ministra Kultury i Dziedzictwa Narodowego pochodzących z Funduszu Promocji Kultury, uzyskanych z dopłat ustanowionych w grach objętych monopolem państwa, zgodnie z art. 80 ust. 1 ustawy z dnia 19 listopada 2009 r. o grach hazardowych, w ramach programu „Muzyczny ślad” realizowanego przez Instytut Muzyki i Tańca ISBN Muzeum Sztuki w Łodzi 978-83-66696-03-7 ISBN Krytyka Polityczna 978-83-66586-44-4 Spis treści Od wydawcy Michał Mendyk i Agnieszka Pindera 9 Polak melduje z kosmosu Szkic do biografii Eugeniusza Rudnika Bolesław Błaszczyk 15 Peregrynacje Pana Podchorążego A pośrodku ryczy lew Z Eugeniuszem Rudnikiem rozmawia Zuzanna Solakiewicz 175 I to jest poezja, jakiej potrzebuję. Rudnik w laboratorium słowa Bolesław Błaszczyk 197 Spis treści Spis Szkice do portretu mistrza Ręce garncarza Daniel Muzyczuk i Agnieszka Pindera 233 Reżyseria: Eugeniusz Rudnik Jan Topolski 251 To nie jest Śpiewnik domowy Eugeniusza Rudnika Michał Mendyk 265 Eugeniusz Rudnik. Kalendarium twórczości i realizacji Bolesław Błaszczyk 317 Bibliografia 351 Indeks 359 Od wydawcy OD WYDAWCY MICHAŁ MENDYK i AGNIESZKA PINDERA Ptacy i ludzie.