Petitioners, V. Respondents. ___

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ARNOLD MITTELMAN Producer/Director 799 Crandon

ARNOLD MITTELMAN Producer/Director 799 Crandon Boulevard, #505 Key Biscayne, FL 33149 [email protected] ARNOLD MITTELMAN is a producer and director with 40 years of theatrical achievement that has resulted in the creation and production of more than 300 artistically diverse plays, musicals and special events. Prior to coming to the world famous Coconut Grove Playhouse in 1985, Mr. Mittelman directed and produced Alone Together at Broadway's Music Box Theatre. Succeeding the esteemed actor José Ferrer as the Producing Artistic Director of Coconut Grove Playhouse, he continued to bring national and international focus to this renowned theater. Mr. Mittelman helped create more than 200 plays, musicals, educational and special events on two stages during his 21-year tenure at the Playhouse. These plays and musicals were highlighted by 28 World or American premieres. This body of work includes three Pulitzer Prize-winning playwrights directing their own work for the first time in a major theatrical production: Edward Albee - Seascape; David Auburn - Proof; and Nilo Cruz - Anna In the Tropics. Musical legends Cy Coleman, Charles Strouse, Jerry Herman, Jimmy Buffett, John Kander and Fred Ebb were in residence at the Playhouse to develop world premiere productions. The Coconut Grove Playhouse has also been honored by the participation of librettist/writers Herman Wouk, Alfred Uhry, Jerome Weidman and Terrence McNally. Too numerous to mention are the world famous stars and Tony award-winning directors, designers and choreographers who have worked with Mr. Mittelman. Forty Playhouse productions, featuring some of the industry's greatest theatrical talents and innovative partnerships between the not-for-profit and for-profit sectors, have transferred directly to Broadway, off-Broadway, toured, or gone on to other national and international venues (see below). -

Undergraduate Play Reading List

UND E R G R A DU A T E PL A Y R E A DIN G L ISTS ± MSU D EPT. O F T H E A T R E (Approved 2/2010) List I ± plays with which theatre major M E DI E V A L students should be familiar when they Everyman enter MSU Second 6KHSKHUGV¶ Play Hansberry, Lorraine A Raisin in the Sun R E N A ISSA N C E Ibsen, Henrik Calderón, Pedro $'ROO¶V+RXVH Life is a Dream Miller, Arthur de Vega, Lope Death of a Salesman Fuenteovejuna Shakespeare Goldoni, Carlo Macbeth The Servant of Two Masters Romeo & Juliet Marlowe, Christopher A Midsummer Night's Dream Dr. Faustus (1604) Hamlet Shakespeare Sophocles Julius Caesar Oedipus Rex The Merchant of Venice Wilder, Thorton Othello Our Town Williams, Tennessee R EST O R A T I O N & N E O-C L ASSI C A L The Glass Menagerie T H E A T R E Behn, Aphra The Rover List II ± Plays with which Theatre Major Congreve, Richard Students should be Familiar by The Way of the World G raduation Goldsmith, Oliver She Stoops to Conquer Moliere C L ASSI C A L T H E A T R E Tartuffe Aeschylus The Misanthrope Agamemnon Sheridan, Richard Aristophanes The Rivals Lysistrata Euripides NIN E T E E N T H C E N T UR Y Medea Ibsen, Henrik Seneca Hedda Gabler Thyestes Jarry, Alfred Sophocles Ubu Roi Antigone Strindberg, August Miss Julie NIN E T E E N T H C E N T UR Y (C O N T.) Sartre, Jean Shaw, George Bernard No Exit Pygmalion Major Barbara 20T H C E N T UR Y ± M ID C E N T UR Y 0UV:DUUHQ¶V3rofession Albee, Edward Stone, John Augustus The Zoo Story Metamora :KR¶V$IUDLGRI9LUJLQLD:RROI" Beckett, Samuel E A R L Y 20T H C E N T UR Y Waiting for Godot Glaspell, Susan Endgame The Verge Genet Jean The Verge Treadwell, Sophie The Maids Machinal Ionesco, Eugene Chekhov, Anton The Bald Soprano The Cherry Orchard Miller, Arthur Coward, Noel The Crucible Blithe Spirit All My Sons Feydeau, Georges Williams, Tennessee A Flea in her Ear A Streetcar Named Desire Synge, J.M. -

Michael Schweikardt Design

Michael Schweikardt Scenic Designer United Scenic Artists Local 829 624 Galen Drive State College, PA 16803 917.674.4146 [email protected] www.msportfolio.com Curriculum Vitae Education Degrees MFA Scenic Design, The Pennsylvania State University, School of Theatre, University Park, 2020. Monograph: On the Ontology and Afterlife of the Scenic Model Committee: Daniel Robinson; Milagros Ponce de Leon; Laura Robinson; Charlene Gross; Richard St. Clair Studied under: Dr. Jeanmarie Higgins; Sebastian Trainor; Dr. Susan Russell; Dr. William Doan; Rick Lombardo BFA Scenic and Costume Design, Rutgers University, Mason Gross School of the Arts, New Brunswick, NJ, 1993. Studied under: John Jensen; R. Michael Miller; Desmond Heeley; David Murin; Vickie Esposito Academic Appointments Graduate Assistant, The Pennsylvania State University, State College, PA School of Theatre, 2017-present Adjunct Professor, Bennington College, Bennington, VT School of Theatre, 2014 Publications and Academic Presentations Book Chapters “Deep Thought: Teaching Critical Theory to Designers” with Dr. Jeanmarie Higgins in Teaching Critical Performance Theory in Today’s Theatre Classroom, Studio, and Communities. Ed. Jeanmarie Higgins. London: Routledge, 2020. Journal Issues Schweikardt, Michael and Jeanmarie Higgins. “Dramaturgies of Home in On- and Off- Stage Spaces.” Etudes: An Online Theatre and Performance Studies Journal for Emerging Scholars. 5:1 (2019). Peer-Reviewed Journal Publications Schweikardt, Michael. “Deep When: A Basic Philosophy for Addressing Holidays in Historical Dramas.” Text and Presentation, 2019 (2020): 63-77. Other Publications Co-Editor, Design, The Theatre Times, 2017-present. “I Can’t Hear You in the Dark: How Scenic Designer Sean Fanning Negotiates the Deaf and Hearing Worlds”, 2019. “Designing for Site-Specific Theatre: An Interview with Designer Susan Tsu on her Costumes for King Lear at Quantum Theatre”, 2019. -

Angela Anna Giron MFA (602) 380-5117 [email protected]

Angela Anna Giron MFA (602) 380-5117 [email protected] EDUCATION: Arizona State University Katherine K. Herberger College of Fine Arts Tempe, AZ Masters of Fine Arts: Theatre – Performance May, 2005 Arizona State University Tempe AZ Bachelor of Arts - Cum Laude - Theatre May, 2002 TEACHING & ADMINISTRATION: ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY Tempe Campus Program Director 2020 Assistant Program Director: 2016 - 2019 Interim Director: Fall 2018 Assistant Clinical Professor & Founding Faculty – Master of Liberal Studies Program (MLSt) - Current Courses: Graduate Seminars – Film Analysis & Cultural Taboo/Texts/Visual Texts, Reality TV, Food Film & Culture, Critical Issues in the Humanities, Crimes and Punishments (Texts & Visual Texts), 1950s – A Decade of Denial, 1960s – A Decade of Turmoil, 1970s – A Decade of Upheaval & Transformation, Film Philosophy, Practicum Faculty Associate – School of Theatre and Film- Herberger Institute of Design and the Arts Courses: Classical Poetic Drama – Performance, Acting 101, Acting 202 Polytechnic Campus Faculty Associate – School of Letters and Sciences Theatre, Communication & Film Studies Courses: Introduction to Film Studies, Studies in International Films, Great Directors, Introduction to Oral Interpretation Former Courses taught: Introduction to Theatre, Introduction to Acting ESTRELLA MOUNTAIN COMMUNITY COLLEGE Fall 2005 - 2012 Faculty Associate – Arts, Communication and Languages: Courses: Cultural Viewpoints in the Arts, Women and Society, The Art of Storytelling, Contemporary Cinema, Introduction to -

CURRICULUM GUIDE for THA 50 – Introduction to Theatre Arts

CURRICULUM GUIDE for THA 50 – Introduction to Theatre Arts Department of Communications & Performing Arts Submitted: Fall 2014; Revised: Fall 2020 Textbook (adopted as of Spring 2018): Theatrical Worlds (Beta Version) Edited by Charlie Mitchell Publisher: University Press of Florida, © 2014 https://ufdc.ufl.edu/AA00021870/00001 NOTE: As this is a “guide”, the sample units, overall topics and progression are a guideline as to what should be covered throughout this introductory survey course. That said, your course should not look dramatically different than what is outlined below and the information herein should be explored in some manner. The plays listed at the end are available through the CUNY Library system. A valid login is required to access these e-versions. Course Description: This survey course is designed to provide students with a thorough understanding and greater appreciation of the theatrical form. Readings and lectures will focus on the relationship between theatrical theory and practice, the various creative/production roles essential to theatre, as well as major artists and movements throughout theatrical history. Students will analyze major works of dramatic literature to offer context for course content, as well as attend a live theatrical performance on campus. Course Objectives: CUNY Flexible Core Learning Outcomes • Gather, interpret, and assess information from a variety of sources and points of view. • Evaluate evidence and arguments critically or analytically. • Produce well-reasoned written or oral arguments using evidence to support conclusions. Revised Course Specific Objectives Theatrical Theories & Terminology: Identify and apply the fundamental concepts, theories and roles associated with modern theatrical practice and professional theatrical production (i.e. -

Anna in the Tropics by Nilo Cruz

Anna in the Tropics By Nilo Cruz Director's Concept Ofeila says to Marela, “That’s why the writer describes love as a thief. The thief is the mysterious fever that poets have been studying for years.” For me the play is all about the love for something (change, companionship, art, work, etc.) that humanity struggles for, and that ultimately is that “stolen” aspect of who and what we are as individuals. It is Cruz’s words, characters, and the relationship that these characters have with the story Anna Karenina that is the catalyst for their love. It is a political love, a self-love, a love of someone else, and a love for change that drives these characters to create their own endings. Cruz remarked in one of his interviews that, “Cuba has changed tremendously. I have changed, too. I guess sometimes I fear what the impact of going back would be on me.” This is a perfect example of each character in the play. Conceptually, change is ultimately the downfall or co-requisite to the love that these characters emote internally and externally. It becomes the underlying motivation for the story (i.e. the introduction of the cigar roller versus the work of the individual, the fact that “lectores” were removed from factories in 1931, and Conchita’s need to be loved physically versus watching her husband have what she does not). In evoking the lost Cuban-American world of Ybor, Florida cigar factory in the late 1920’s, I want to create a production that is as “novela-like” as the emotions and tribulations as its characters. -

Anna in the Tropics

Presents ANNA IN THE TROPICS by Nilo Cruz Directed by Jon Lawrence Rivera Featuring Christopher Cedeño • Presciliana Esparolini • Antonio Jaramillo* Javi Mulero* • Byron Quiros* • Jill Remez* Jade Santana • Steve Wilcox • Jennifer Zorbalas Scenic Design Costume Design Lighting Design Christopher Scott Murillo Mylette Nora Matt Richter Sound Design Properties Dialect Coach Tim Labor Bruce Dickinson & Ina Shumaker Tuffet Schmelzle Scenic Construction Rehearsal Stage Manager Assoc Lighting Design Jan Munroe Therese Olson Kaitlin Chang Associate Producer Production Stage Manager Publicist Beth Robbins Benjamin Scuglia Lucy Pollak Produced by Martha Demson Roger Berlind, Daryl Roth, Ray Larsen, in association with Robert Bartner presented the New York premiere of Anna in the Tropics at the Royale Theatre. Anna in the Tropics was originally commissioned and produced by New Theatre, Coral Gables, FL, Rafael de Acha, Artistic Director; Eileen Suarez, Managing Director, through a residency grant from Theatre Communications Group and the National Endowment for the Arts. It was subsequently produced by South Coast Repertory, Costa Mesa, CA, David Emmes, Producing Artistic Director; Paula Tomei, Managing Director, and at the McCarter Theatre Center, Princeton, NJ, Emily Mann, Artistic Director; Jeffrey Woodward, Managing Director. The McCarter Theatre Center production transferred to Broadway. *Member, Actors’ Equity Association, the Union of Professional Actors and Anna in the Tropics is supported, in part, Stage Managers in the United States. by the Los Angeles County Board of This production is presented under the Supervisors through the LA County Arts auspices of the Actors’ Equity Los Commission. Angeles Membership Company Rule. The Scenic Designer is a member of United Scenic Artists, a national theatrical labor union. -

By Jane Austen Kyle Donnelly

48th Season • 455th Production SEGERSTROM STAGE / SEPTEMBER 9 - OCTOBER 9, 2011 Marc Masterson Paula Tomei ARTiSTiC DiRECTOR MAnAGinG DiRECTOR David Emmes & Martin Benson FOUNDING ARTiSTiC DiRECTORS presents Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen Adapted for the stage by Joseph Hanreddy and J.R. Sullivan Kate Edmunds Paloma H. Young Lap Chi Chu SCEniC DESiGn COSTUME DESiGn LiGHTinG DESiGn Michael Roth Sylvia C. Turner Adam Flemming ORiGinAL MUSiC/MUSiC DiRECTiOn CHOREOGRAPHER ASST. SCEniC DESiGn/ PROjECTiOn COORDinATOR Ursula Meyer & Eva Barnes Joshua Marchesi Jamie A. Tucker* DiALECT COACHES PRODUCTiOn MAnAGER STAGE MAnAGER Directed by Kyle Donnelly Tom and Marilyn Sutton & Jean and Tim Weiss Honorary Producers Corporate Producer Pride and Prejudice • SOUTH COAST REPERTORY • P1 CAST OF CHARACTERS (in order of appearance) The Girl ............................................................................................ Claire Kaplan* Lady Lucas/Mrs. Gardiner ..................................................................... Eva Barnes* Mrs. Bennet ............................................................................................. Jane Carr* Mr. Bennet ...................................................................................... Randy Oglesby* Catherine (Kitty) Bennet ............................................................. Elizabeth Nolan* Lydia Bennet ........................................................................................ Amalia Fite* Elizabeth Bennet ................................................................................ -

Is a Graduate of the Crane School of Music (Voice/Patricia Misslin)

CATS JOHN ANTHONY LOPEZ (Old Deuteronomy) is a graduate of the Crane School of Music (voice/Patricia Misslin). Regional Credits include: Beauty and the Beast (Beast), South Pacific (Emile), Jane Eyre (Rochester), La Traviata (Alfredo), The Magic Flute (Tamino). NYC/Metro Credits include: Fiddler on the Roof/VLOG NYC (Tevye), The Seed of Abraham FringeNYC (Joshua), The Man in the Iron Mask/WVMTF (Aramis), 7:32 the musical/reading (Charles Collins), Into the Woods/NJ (Baker). Love and thanks to his son, Corey, who keeps him afloat. Thanks Kiddo. johnanthonylopez.com DAVID RAIMO* (Munkustrap) honored to be playing the role of Munkustrap with the WPPAC family. Originally from Duluth, MN, David headed south to attend college at Oklahoma City University where he earned his B.F.A. in Musical Theater. After graduating in '07, David has performed on four Broadway National Tours including: Chicago (Fred Casely/Billy Flynn), CATS (Munkustrap), Joseph ...Dreamcoat (Simeon), and Mamma Mia! (Sky). Other favorite credits: Guys and Dolls (Ensemble) at the Hollywood Bowl, the world premiere of Life Could Be A Dream (Skip) and Damn Yankees (Joe Hardy). David would like to thanks his family and friends for their endless support. www.davidraimo.com DEVON YATES* (Grizabella) is thrilled to be making her WPPAC debut with CATS, and is proud to be walking in the footsteps her mother did as Grizabella a few years ago! A native to the small town of Edinboro, PA, she is a 2010 Music Theatre graduate of Baldwin-Wallace College Conservatory of Music, and now currently resides in NYC. Some of her past Regional credits include: Lippa's Wild Party(Queenie), Parade(Lucille Frank), Evita(Eva Peron), the non-union premiere of ALW's Phantom of the Opera(Carlotta Guidicelli), the regional premiere of BKLYN: the Musical(Faith), and Chess(Florence). -

Drama Winners the First 50 Years: 1917-1966 Pulitzer Drama Checklist 1966 No Award Given 1965 the Subject Was Roses by Frank D

The Pulitzer Prizes Drama Winners The First 50 Years: 1917-1966 Pulitzer Drama Checklist 1966 No award given 1965 The Subject Was Roses by Frank D. Gilroy 1964 No award given 1963 No award given 1962 How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying by Loesser and Burrows 1961 All the Way Home by Tad Mosel 1960 Fiorello! by Weidman, Abbott, Bock, and Harnick 1959 J.B. by Archibald MacLeish 1958 Look Homeward, Angel by Ketti Frings 1957 Long Day’s Journey Into Night by Eugene O’Neill 1956 The Diary of Anne Frank by Albert Hackett and Frances Goodrich 1955 Cat on a Hot Tin Roof by Tennessee Williams 1954 The Teahouse of the August Moon by John Patrick 1953 Picnic by William Inge 1952 The Shrike by Joseph Kramm 1951 No award given 1950 South Pacific by Richard Rodgers, Oscar Hammerstein II and Joshua Logan 1949 Death of a Salesman by Arthur Miller 1948 A Streetcar Named Desire by Tennessee Williams 1947 No award given 1946 State of the Union by Russel Crouse and Howard Lindsay 1945 Harvey by Mary Coyle Chase 1944 No award given 1943 The Skin of Our Teeth by Thornton Wilder 1942 No award given 1941 There Shall Be No Night by Robert E. Sherwood 1940 The Time of Your Life by William Saroyan 1939 Abe Lincoln in Illinois by Robert E. Sherwood 1938 Our Town by Thornton Wilder 1937 You Can’t Take It With You by Moss Hart and George S. Kaufman 1936 Idiot’s Delight by Robert E. Sherwood 1935 The Old Maid by Zoë Akins 1934 Men in White by Sidney Kingsley 1933 Both Your Houses by Maxwell Anderson 1932 Of Thee I Sing by George S. -

Download 2012–2013 Catalogue of New Plays

Cover Spread 1213.ai 7/24/2012 12:18:11 PM Inside Cover Spread 1213.ai 7/24/2012 12:14:50 PM NEW CATALOGUE 12-13.qxd 7/25/2012 10:25 AM Page 1 Catalogue of New Plays 2012–2013 © 2012 Dramatists Play Service, Inc. Dramatists Play Service, Inc. A Letter from the President Fall 2012 Dear Subscriber, This year we are pleased to add over 85 works to our Catalogue, including both full length and short plays, from our new and established authors. We were particularly fortunate with nominations and awards that our authors won this year. Quiara Alegría Hudes won the Pulitzer Prize with WATER BY THE SPOONFUL, and the two runners-up were John Robin Baitz’s OTHER DESERT CITIES and Stephen Karam’s SONS OF THE PROPHET. The Play Service also represents three of the four 2012 Tony nominees for Best Play, including the winner, Bruce Norris’ CLYBOURNE PARK, Jon Robin Baitz’s OTHER DESERT CITIES and David Ives’ VENUS IN FUR. All four of the Tony nominations for Best Revival are represented by the Play Service: DEATH OF A SALESMAN (the winner), THE BEST MAN, MASTER CLASS and WIT. Other new titles include Rajiv Joseph’s BENGAL TIGER AT THE BAGHDAD ZOO, David Henry Hwang’s CHINGLISH, Katori Hall’s THE MOUNTAINTOP, Nina Raines’ TRIBES and Paul Weitz’s LONELY, I’M NOT. Newcomers to our Catalogue include Simon Levy, whose masterful adaptation of THE GREAT GATSBY is the only stage version to be authorized by the Fitzgerald Estate; Erika Sheffer, with her vivid portrait of an immigrant family in RUSSIAN TRANSPORT; Sarah Treem, with her absorbing and thought-provoking THE HOW AND THE WHY; and Tarell Alvin McCraney, with the three plays of his critically acclaimed BROTHER/SISTER TRILOGY. -

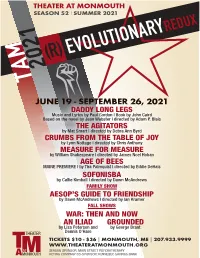

2021 Program Book

THEATER AT MONMOUTH SEASON 52 I SUMMER 2021 EDUX IONARYR EVOLUT M (R) 2021 TA JUNE 19 - SEPTEMBER 26, 2021 DADDY LONG LEGS Music and Lyrics by Paul Gordon I Book by John Caird Based on the novel by Jean Webster I directed by Adam P. Blais THE AGITATORS by Mat Smart I directed by Debra Ann Byrd CRUMBS FROM THE TABLE OF JOY by Lynn Nottage I directed by Chris Anthony MEASURE FOR MEASURE by William Shakespeare I directed by James Noel Hoban AGE OF BEES MAINE PREMIERE I by Tira Palmquist I directed by Eddie DeHais SOFONISBA by Callie Kimball I directed by Dawn McAndrews FAMILY SHOW AESOP’S GUIDE TO FRIENDSHIP by Dawn McAndrews I directed by Ian Kramer FALL SHOWS WAR: THEN AND NOW AN ILIAD GROUNDED by Lisa Peterson and by George Brant THEATER Dennis O’Hare TICKETS $10 - $36 | MONMOUTH, ME | 207.933.9999 T WWW.THEATERATMONMOUTH.ORG MAT SEASON SPONSOR: MAIN STREET PSYCHOTHERAPY AMONMOUTH ACTING COMPANY CO-SPONSOR: KENNEBEC SAVINGS BANK W e are proud to support the Theater at M onm outh Enjoy the show ! Augusta (207) 622-5801 Farmingdale (207) 588-5801 • Freeport (207) 865-1550 Winthrop (207) 377-5801 • Waterville (207) 872-5563 www.KennebecSavings.Bank Maine’s Black Business Directory BOM Podcast BIPOC Mutual Aid Business Incubator Marketing and blackownedmaine.com Advertising @blackownedmaine E business cards | posters L B presentation folders newsletters | reports IA L labels | booklets | envelopes postcards | banners | menus RE • rack cards | brochures | forms promotional items | lawn signs ST laminating | letterhead | foam core A F tabs | scanning | post it note pads £Ç7iÃÌwi`-ÌÀiiÌ • *ÀÌ>`] ä{£äÓ booklets | calendars | invitations L 207.775.2444 manuals | handouts | binding A orders @xcopy.com C direct mailings | legal briefs | blueprints WWW.XCOPY.COM O AND MORE! L 4 | THEATER AT MONMOUTH SEASON 52 REVOLUTIONARY REDUX TABLE OF CONTENTS DADDY LONG LEGS Music and Lyrics by Paul Gordon Book by John Caird About Theater at Monmouth 6 Based on the novel by Jean Webster | directed by Adam P.