Review of Raffaelli Et Al. Lexicalization Patterns in Color Naming A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

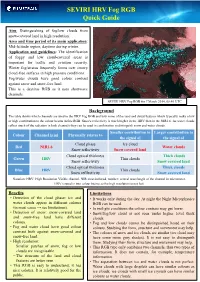

SEVIRI HRV Fog RGB Quick Guide

SEVIRI HRV Fog RGB Quick Guide Aim: Distinguishing of fog/low clouds from snow-covered land in high resolution. Area and time period of its main application: Mid-latitude region, daytime during winter. Application and guidelines: The identification of foggy and low cloud-covered areas is important for traffic and aviation security. Winter fog/stratus frequently forms over snowy cloud-free surfaces in high pressure conditions. Fog/water clouds have good colour contrast against snow and snow-free land. This is a daytime RGB as it uses shortwave channels. SEVIRI HRV Fog RGB for 7 March 2014, 08:40 UTC Background The table shows which channels are used in the HRV Fog RGB and lists some of the land and cloud features which typically make a low or high contribution to the colour beams in this RGB. Snow's reflectivity is much higher in the HRV than in the NIR1.6. As water clouds reflect much of the radiation in both channels they can be used in combination to distinguish snow and water clouds. Smaller contribution to Larger contribution to Colour Channel [µm] Physically relates to the signal of the signal of Cloud phase Ice cloud Red NIR1.6 Water clouds Snow reflectivity Snow covered land Cloud optical thickness Thick clouds Green HRV Thin clouds Snow reflectivity Snow covered land Cloud optical thickness Thick clouds Blue HRV Thin clouds Snow refllectivity Snow covered land Notation: HRV: High Resolution Visible channel, NIR: near-infrared, number: central wavelength of the channel in micrometer. HRV is used in two colour beams so the high resolution is not lost. -

Social and Cultural Transformations in the Context of Modern Globalism”

The European Proceedings of Social & Behavioural Sciences EpSBS Future Academy ISSN: 2357-1330 https://dx.doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2019.03.02.235 SCTCMG 2018 International Scientific Conference “Social and Cultural Transformations in the Context of Modern Globalism” СOLOUR NAMING IN OSSETIAN LANGUAGE: LINGUOCULTURAL ASPECT Rita Tsopanova (a), Larisa Gatsalova (b)*, Angela Kudzoeva (с), Aza Gazdarova (d), Ida Khozieva (е) *Corresponding author (a) North Ossetian State University, 44-46 Vatutina Str., Vladikavkaz, Russia, (b) North Ossetian State University named after K. L. Khetagurov, Vladikavkaz Scientific Center RAS, 10 Mira, Ave., Vladikavkaz, Russia, (c) North Ossetian State University, 44-46 Vatutina Str., Vladikavkaz, Russia, (d) North Ossetian State University, 44-46 Vatutina Str., Vladikavkaz, Russia, (e) North Ossetian State University, 44-46 Vatutina Str., Vladikavkaz, Russia, Abstract The paper explores core and peripheral color lexicon and shades in Ossetian language. Derived, complex words and analytical structures transmit shades of colors. Four colors have the highest use frequency in Ossetian language: black, white, red and blue. Black and white colors have the greatest semantic and stylistic meaning in the speech of Ossetian linguistic culture. These colors are precisely the part of mental language formations. An important role in color features of objective world is played by yellow and gold that is close to it. Blue, green and gray are named by one color. Color words have connotative meanings, express the peculiarities in people mentality and participate in symbol formation and stereotypes. Individual author’s development of color vocabulary enriches visual and expressive possibilities in Ossetian language. This study gives an idea of color picture of the world in the minds of the Ossetians. -

The War and Fashion

F a s h i o n , S o c i e t y , a n d t h e First World War i ii Fashion, Society, and the First World War International Perspectives E d i t e d b y M a u d e B a s s - K r u e g e r , H a y l e y E d w a r d s - D u j a r d i n , a n d S o p h i e K u r k d j i a n iii BLOOMSBURY VISUAL ARTS Bloomsbury Publishing Plc 50 Bedford Square, London, WC1B 3DP, UK 1385 Broadway, New York, NY 10018, USA 29 Earlsfort Terrace, Dublin 2, Ireland BLOOMSBURY, BLOOMSBURY VISUAL ARTS and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published in Great Britain 2021 Selection, editorial matter, Introduction © Maude Bass-Krueger, Hayley Edwards-Dujardin, and Sophie Kurkdjian, 2021 Individual chapters © their Authors, 2021 Maude Bass-Krueger, Hayley Edwards-Dujardin, and Sophie Kurkdjian have asserted their right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identifi ed as Editors of this work. For legal purposes the Acknowledgments on p. xiii constitute an extension of this copyright page. Cover design by Adriana Brioso Cover image: Two women wearing a Poiret military coat, c.1915. Postcard from authors’ personal collection. This work is published subject to a Creative Commons Attribution Non-commercial No Derivatives Licence. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher Bloomsbury Publishing Plc does not have any control over, or responsibility for, any third- party websites referred to or in this book. -

Graphics Standards Guide Primary Logo

GRAPHICS STANDARDS GUIDE PRIMARY LOGO This City of Hays logo should never be re-created or re-typeset. To maintain consistency, a cohesive balance, and a strong visual identity, the City of Hays logo should only be used from existing digital files. CLEAR ZONE The City of Hays logo should always have an area of open space or “clear zone” around it. No other graphic elements should fall within this area around the logo. Where the “X” is equal to the height of the capital (H) in the word “Hays”, leave at least X amount of clearance on all sides of the logo. MINIMUM SIZES The City of Hays logo should always be used at an appropriate size to make sure it is legible. When the primary logo is used, it should be no smaller 1.0625 than 1.0625” at its widest point. COLOR PALETTE This City of Hays logo is composed of 2 colors with a tint of 25% through the abstract (h) logo. Four-color process printing is the preferred option for printing. When the logo is used on the web or on screen, the RGB format should be used. Four-color process, Pantone and RGB formulas are listed below. MAIN BRAND COLORS 4-COLOR PROCESS (CMYK) SPOT COLOR (PANTONE) RGB & HEX VALUE (WEB) C 0 PMS 7406 R 241 M 13 G 196 Y 100 B 0 25% tint 25% tint 25% tint K 1 HEX #F1C400 Yellow Yellow Yellow C 63 PMS BLACK 7 R 61 M 60 G 57 Y 64 B 53 K 65 HEX #3D3935 Black 7 Black 7 Black 7 LOGO FONT Gotham Book and Gotham Black are the two fonts for the City of Hays text of the logo. -

13 Shades of Black PR

Black Wednesday Social Co. Launches 13 Shades of Black Series FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: May 3, 2016 (CHARLOTTE, NORTH CAROLINA) – Charlotte-based Black Wednesday Social Co. to release a new 13- week series, “13 Shades of Black,” on Wednesday, May 4th, 2016. The series will feature local fashion makers, designers and artists as styled in the color black. Black Wednesday Social Co. is a boutique marketing company based in Charlotte, North Carolina that specializes in showcasing the human element. Through its brand personification services, BW custom builds marketing strategies that are tailored to fit your needs, with the goal of helping you share the living, breathing human passion behind exactly what it is that gets you up in the morning (besides coffee). Because yes, Black Wednesday is a big fan of coffee: but an even bigger fan of the conversations that happen over a cup of coffee. So, what’s your next conversation? Black Wednesday whole-heartedly believes in building community through social media and designed the series to do such. The first BW series, “#cyoWedventure,” was a weekly meet up series launched in December of 2015. Every Monday a theme was announced and BW followers voted on their favorite places followed by a Wednesday meet up at the winning spot. The second series, “13 Shades of Black” features Charlotte fashion influencers and how they would style themselves in Black Wednesday’s favorite color; photos were taken by local fashion photographer, Katherine Kirchner. Over 13 Wednesdays, each of the involved will be revealed over the @bwsocialco social media and blog channels. -

Spring Wines

Written by Doug Werner & Kenneth Go Produced by Green’s Discount Beverages Spring 2017 Greenville (864) 297-6353 Myrtle Beach (843) 448-1623 Columbia (803) 744-0570 Columbia (803) 799-9499 445 Congaree Rd 2850 N. Kings Hwy. 4012B Fernandina Rd. 400 Assembly St. Greenville, SC 29607 Myrtle Beach, SC 29577 Columbia, SC 29212 Columbia, SC 29201 Jessica Gulotta (Wine Consultant) Erin Hester (Sales Associate) Kurt Huffstetler (Wine Consultant) Kat Kaster (Wine Consultant) Elaine Dillard (Sales Associate) Jordan Jones (Sales Associate) SPRING WINES The Tasting Team Has Spent The Last Couple Of Months Searching For Special Wines For Your Spring Time Enjoyment. We Have Found Selections From All Over The World, In Red And White And Rose. Wines From Australia, France, Italy, New Zealand, Spain, And The Good Old Usa Are Listed Below. How About A Crisp Vouvray From Loire Valley Or Sauignon Blanc From New Zealand? Amaze Your Friends With A Dry Rose. There Are So Many Styles Of Wine Out There It Seems A Shame To Concentrate On One Or Two Types, No Matter How Delicious They Are. RED WINES Pepperjack Barossa Red Blend Peter Lehmann Clancy’s Barossa 2013 Red Blend 2014 Green’s Cash Sale Price: $14.99 Green’s Cash Sale Price: $10.99 *National Average Retail Price: $18.00 *National Average Retail Price: $15.00 “This wine has lots of upfront fruit while having a “Supple and appealing, with juicy wild berry soft round structure and a slight hint of oak. The and cherry flavors at the core. Cedar, spice and aromas and flavor show fresh berries, plums and white pepper notes linger in the background. -

Looking at Skin Color with Books and Activities

Looking at Skin Color with Books and Activities All the Colors of the Earth. Sheila Hamanaka. Celebrate the colors of children and the colors of love--not black or white or yellow or red, but roaring brown, whispering gold, tinkling pink, and more. All the Colors We Are/Todos los colores de nuestra piel: The Story of How We Get Our Skin Color/La historia de por qué tenemos diferentes colores de piel. Katie Kissinger. Offers children a simple, scientifically accurate explanation about how our skin color is determined by our ancestors, the sun, and melanin. The colorful photographs capture the beautiful variety of skin tones. Activity ideas are included. 20th Anniversary Edition. Chocolate Me! Taye Diggs. Teased for looking different than the other kids—his skin is darker, his hair curlier—he tells his mother he wishes he could be more like everyone else. And she helps him to see how beautiful he really, truly is. The Colors of Us. Karen Katz. A positive and affirming look at skin color, from an artist’s perspective. Seven-year-old Lena wants to use brown paint for her skin in a picture of herself. But when she and her mother walk through the neighborhood, Lena learns that brown comes in many different shades. M is for Melanin. Tiffany Rose. (Toddler – K) Each letter of the alphabet contains affirming, Black-positive messages, from A is for Afro and F is for Fresh to P is for Pride and W is for Worthy. Teaches children their ABCs while encouraging them to love the skin they're in. -

K9YA Telegraph Robert F

K9YA Telegraph Robert F. Heytow Memorial Radio Club Volume 17, Issue 10 October 2020 Andy Hardy’s QSP “W8XZR” Relays Judge Hardy’s Traffic Philip Cala-Lazar, K9PL Place Art work Here he K9YA Facebook page Bringham[?] Canada”); manual receiver/transmitter T(https://www.facebook. switching; plentiful ID’ing from both operators; and com/k9ya.telegraph) recently the casual use of ham radio jargon including “73,” linked an oft viewed but little “Old Man,” “QSL card” and “DX.” researched film clip from the 1938 MGM movie, Love For an instant, in a medium shot, a number of QSL Finds Andy Hardy. In that cards displayed on the wall behind the operating desk https://vimeo.com/248714142 clip Andy Hardy’s (Mickey are clearly visible ( ); freezing the frame they are the cards of W6DTA, Rooney) father, Judge Hardy W6ESD, W6NYD, W6OWM and K6PAS. Philip Cala-Lazar, K9PL (Lewis Stone), wants to send a message (from Carvel, Editor in an unnamed Midwestern state) to Extracted from the spring 1939 edi- his wife, Emily (Fay Holden). Trouble Mike Dinelli, N9BOR tion of the Radio Amateur Call Book: Layout is Mrs. Hardy is caring for her mother, W6DTA, Albert W. Brunner, 940 who recently suffered a stroke, at a Cedar St., San Carlos, Calif.; W6ESD, Jeff Murray, K1NSS Staff Cartoonist farm in rural Ontario, Canada where A.G. Neumann, 1228 Rimpau Blvd., there’s no telephone and telegrams “plentiful ID’ing” Los Angeles, Calif.; W6NYD, [Lt.] unnerve his wife. Andy suggests that A.W. Greenlee,* 621 I Ave., Coronado, 12-year-old amateur radio operator Calif.; W6OWM, Leo G. -

"Fifty Shades of Black": the Black Racial Identity Development Of

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 4-15-2018 "Fifty Shades of Black": The lB ack Racial Identity Development of Black Members of White Greek Letter Organizations in the South Danielle Ford Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Educational Leadership Commons, Higher Education Commons, and the Higher Education Administration Commons Recommended Citation Ford, Danielle, ""Fifty Shades of Black": The lB ack Racial Identity Development of Black Members of White Greek Letter Organizations in the South" (2018). LSU Master's Theses. 4697. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/4697 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “FIFTY SHADES OF BLACK”: THE BLACK RACIAL IDENTITY DEVELOPMENT OF BLACK MEMBERS OF WHITE GREEK LETTER ORGANIZATIONS IN THE SOUTH A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The School of Education by Danielle Ford B.S. Louisiana State University, 2012 May 2018 Don’t Quit When things go wrong as they sometimes will, When the road you're trudging seems all up hill, When the funds are low and the debts are high And you want to smile, but you have to sigh, When care is pressing you down a bit, Rest if you must, but don't you quit. -

Central Tech Style and Branding Guide

OUR BRAND LOGO & TAGLINE “Logos” are the representative symbols of an organization. All promotional materials must include the Central Tech logo on the front cover in a prominent size. Whenever possible, the logo should be reproduced as shown in three colors: Central Tech blue, green and orange. It may also be printed all black or reverse (white). Central Tech’s tagline is Elevate Educate Empower. The tagline should be used as a complete line, not broken up and/or separated and remain in the orignal order. In certain situations, elements within the logo, such as the swoosh and the 3E tagline may be removed if objects or text will become illegible once printed. If design issues require a different layout, it must be approved by the marketing department. Anakeim Display is the font used to create the “Central Tech” logo using a modified “e”. Myriad Pro is used to create the 3E tagline. LOGO TREATMENTS - WITH APPROVAL FROM MARKETING DEPARTMENT • Departments - The tagline may be replaced with departmental names. • Apparel - Monograms may appear in blue, black, reverse (white) or shades of black (gray). • Hats are the exception - logo may appear in orange or neon orange on neon mesh or camo. Truck Driver Training • Different formats of the logo for varied print purposes can be obtained from the marketing office. IMPROPER LOGO USE Always use the official logo. Do not attempt to: • Recreate, alter, distort, stretch, compress, crop, angle/rotate, or pixelate the logo, • Place the logo over a texture, pattern, or photograph with a confusing background, • Reduce the logo smaller than 1/4” in height, • Use the official logo in a sentence instead of the words “Central Tech”. -

Spring 2014 Issue of Sagatagan Seasons

AGATAGAN A Vision of Color Tanner Rayman ‘16 S birch tree stands before me. The crisp, rippling expanse of stunning deep-water blues and A flaking bark is an opaque white and stands shallow turquoises. Instead, it is a blackened glass in stark contrast to the rest of the matted browns surface that seems to gladly reflect any light away and greys of the forest. Where the knobs of long from it. E abandoned branches protrude we see glimpses of The human eye is especially adapted to the rich brown core that we know resides under interpret the varying sensations experienced the startling exterior. Further up, the crown of the during times of both high and low-light. In tree explodes into a firework pattern of pearled high-light, such as the careful observation of a branches and green leaves that continually alter birch tree in the daylight, our eye relies on cone their shade and tone in the fluttering wind. cells to sense and compile the information in the A Light illuminates the birch tree’s exterior and environment and send it to the brain. Cone cells the complex gathering of tissues that make up the are also responsible for nearly all of our color tree become distinguishable to the human eye. As vision. We have three different types of cone cells light encounters the tree certain wavelengths of that are most sensitive to red, green, and blue light are absorbed. A deeply green leaf absorbs all light wavelengths. Our eyes sense a mix of these of the wavelengths except those representing the primary colors from the environment and the various shades of green. -

Pigmentocracy

Pigmentocracy Trudier Harris J. Carlyle Sitterson Professor of English, Emerita University of North Carolina National Humanities Center Fellow ©National Humanities Center Definition and Background In the past couple of decades, the word pigmentocracy has come into common usage to refer to the distinctions that people of African descent in America make in their various skin tones, which range from the darkest shades of black to paleness that approximates whiteness. More specifically, the “ocracy” in pigmentocracy carries with it notions of hierarchical value that viewers place on such skin tones. Lighter skin tones are therefore valued more than darker skin tones. Such preferences have social, economic, and political implications, as persons of lighter skin tones historically were frequently—and stereotypically—viewed as being more intelligent, talented, and socially graceful than their darker skinned black counterparts. Blacker blacks were viewed as unattractive, indeed ugly, and generally considered of lesser value. Europeans standards of beauty thus dominated an African people for most of their history in America. Although the word pigmentocracy may have come into widespread usage fairly recently, the concept extends throughout the history of Africans on American soil. During slavery, black people who were fathered by their white masters often gained privileges based on their lighter coloring. Indeed, one reported pattern is that blacks of lighter skin were reputedly selected to work in the Big Houses of plantation masters while blacks of darker hues were routinely sent to the fields. Moreover, one of the origins of the Dozens, the ritual game of insult in African American culture, is reputed to have developed as a result of slurs darker skinned blacks who worked in the fields hurled at lighter skinned blacks because their mothers had given birth to children sired by white masters.