CYNIPID-INDUCED GALLS and CALIFORNIA OAKS by K.N

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Survey of Aphid Parasitoids and Hyperparasitoids (Hymenoptera) on Six Crops in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq

JHR 81: 9–21 (2021) doi: 10.3897/jhr.81.59784 RESEARCH ARTICLE https://jhr.pensoft.net A survey of aphid parasitoids and hyperparasitoids (Hymenoptera) on six crops in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq Srwa K. Bandyan1,2, Ralph S. Peters3, Nawzad B. Kadir2, Mar Ferrer-Suay4, Wolfgang H. Kirchner1 1 Ruhr University, Faculty of Biology and Biotechnology, Universitätsstraße 150, 44801, Bochum, Germany 2 Salahaddin University, Faculty of Agriculture, Department of Plant Protection, Karkuk street-Ronaki 235 n323, Erbil, Kurdistan Region, Iraq 3 Centre of Taxonomy and Evolutionary Research, Arthropoda Depart- ment, Zoological Research Museum Alexander Koenig, Arthropoda Department, 53113, Bonn, Germany 4 Universitat de Barcelona, Facultat de Biologia, Departament de Biologia Animal, Avda. Diagonal 645, 08028, Barcelona, Spain Corresponding author: Srwa K. Bandyan ([email protected]) Academic editor: J. Fernandez-Triana | Received 18 October 2020 | Accepted 27 January 2021 | Published 25 February 2021 http://zoobank.org/284290E0-6229-4F44-982B-4CC0E643B44A Citation: Bandyan SK, Peters RS, Kadir NB, Ferrer-Suay M, Kirchner WH (2021) A survey of aphid parasitoids and hyperparasitoids (Hymenoptera) on six crops in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq. Journal of Hymenoptera Research 81: 9–21. https://doi.org/10.3897/jhr.81.59784 Abstract In this study, we surveyed aphids and associated parasitoid wasps from six important crop species (wheat, sweet pepper, eggplant, broad bean, watermelon and sorghum), collected at 12 locations in the Kurdistan region of Iraq. A total of eight species of aphids were recorded which were parasitised by eleven species of primary parasitoids belonging to the families Braconidae and Aphelinidae. In addition, four species of hyperparasitoids (in families Encyrtidae, Figitidae, Pteromalidae and Signiphoridae) were recorded. -

Jppr 44(4).Vp

PARASITOIDS OF APHIDOPHAGOUS SYRPHIDAE OCCURRING IN CABBAGE APHID (BREVICORYNE BRASSICAE L.) COLONIES ON CABBAGE VEGETABLES Beata Jankowska Agricultural University, Department of Plant Protection Al. 29 Listopada 54, 31-425 Kraków, Poland e-mail: [email protected] Accepted: November29, 2004 Abstract: In 1993–1995 from the cabbage aphid colonies, fed on nine different va- rieties of Brassica oleracea L. syrphid larvae and pupae were collected. The remaining emerged adults of Syrphidae were classified to eight species. The parasitization var- ied within the years of observation and oscillated from 14,4% to 46,4%. Four para- sitic Hymenoptera: Diplazon laetatorius (F.), Diplazon sp., Pachyneuron grande (Thoms.), and Syrphophagus aeruginosus (Dalm.) were reared. The parasitoids identified belong to the following three families Ichneumonidae, Pteromalidae, and Encyrtidae. The larg- est group of reared parasitoids belonged to the family Ichneumonidae of which the most frequent was Diplazon laetatorius (F.). It occurred in each year of observations. The parasitization by D. laetatorius reached 21,7%. Key words : Syrphidae, syrphid parasitoids, Brevicoryne brassicae INTRODUCTION Syrphidae are one of the most important factors decreasing the number of cab- bage aphid Brevicoryne brassicae L. – a main pest of cabbage vegetables (Wnuk 1971; Wnuk and Fusch 1977; Wnuk and Wojciechowicz 1993). Aphidophagous Syrphidae are attacked by a wide range parasitic Hymenoptera, common being Ichneumonidae, Pteromalidae, Megasplidae, Encyrtidae and Figitidae (Scott 1939; Evenhuis 1966; Dusek et al. 1979; Rotheray 1979; 1981a; b; 1984; Kartasheva and Dereza 1981; Pek 1982; Fitton and Rotheray 1982; Radeva 1983; Dean 1983; Thirion 1987; Fitton and Boston 1988). They reduce the number of syrphids and negatively affect their func- tion in the control of aphid populations. -

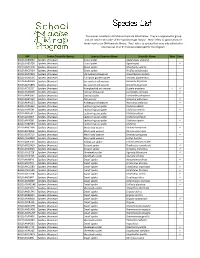

Species List

The species collected in your Malaise trap are listed below. They are organized by group and are listed in the order of the 'Species Image Library'. ‘New’ refers to species that are brand new to our DNA barcode library. 'Rare' refers to species that were only collected in your trap out of all 59 that were deployed for the program. BIN Group (scientific name) Species Common Name Scientific Name New Rare BOLD:AAD1746 Spiders (Araneae) Dwarf spider Erigone aletris BOLD:AAD1498 Spiders (Araneae) Dwarf spider Grammonota angusta BOLD:AAP4796 Spiders (Araneae) Dwarf spider Spirembolus mundus BOLD:AAB0863 Spiders (Araneae) Thinlegged wolf spider Pardosa BOLD:AAB2768 Spiders (Araneae) Running crab spider Philodromus BOLD:ACJ7625 Mites (Arachnida) Mite Ameroseiidae BOLD:AAZ5638 Mites (Arachnida) Phytoseiid mite Phytoseiidae BOLD:AAF9236 Mites (Arachnida) Whirligig mite Anystidae BOLD:ABW5642 Mites (Arachnida) Whirligig mite Anystidae BOLD:AAP7016 Beetles (Coleoptera) Striped flea beetle Phyllotreta striolata BOLD:ABX3225 Beetles (Coleoptera) Flea beetle Psylliodes cucullata BOLD:AAA8933 Beetles (Coleoptera) Seven-spotted lady beetle Coccinella septempunctata BOLD:ACA3993 Beetles (Coleoptera) Snout beetle Dorytomus inaequalis BOLD:AAN9744 Beetles (Coleoptera) Alfalfa weevil Hypera postica BOLD:ACL4042 Beetles (Coleoptera) Weevil Curculionidae BOLD:ABA9093 Beetles (Coleoptera) Minute brown scavenger beetle Corticaria BOLD:ACD4236 Beetles (Coleoptera) Minute brown scavenger beetle Corticarina BOLD:AAH0256 Beetles (Coleoptera) Minute brown scavenger -

Phylogeny and Geological History of the Cynipoid Wasps (Hymenoptera: Cynipoidea) Zhiwei Liu Eastern Illinois University, [email protected]

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Faculty Research & Creative Activity Biological Sciences January 2007 Phylogeny and Geological History of the Cynipoid Wasps (Hymenoptera: Cynipoidea) Zhiwei Liu Eastern Illinois University, [email protected] Michael S. Engel University of Kansas, Lawrence David A. Grimaldi American Museum of Natural History Follow this and additional works at: http://thekeep.eiu.edu/bio_fac Part of the Biology Commons Recommended Citation Liu, Zhiwei; Engel, Michael S.; and Grimaldi, David A., "Phylogeny and Geological History of the Cynipoid Wasps (Hymenoptera: Cynipoidea)" (2007). Faculty Research & Creative Activity. 197. http://thekeep.eiu.edu/bio_fac/197 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Biological Sciences at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Research & Creative Activity by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PUBLISHED BY THE AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY CENTRAL PARK WEST AT 79TH STREET, NEW YORK, NY 10024 Number 3583, 48 pp., 27 figures, 4 tables September 6, 2007 Phylogeny and Geological History of the Cynipoid Wasps (Hymenoptera: Cynipoidea) ZHIWEI LIU,1 MICHAEL S. ENGEL,2 AND DAVID A. GRIMALDI3 CONTENTS Abstract . ........................................................... 1 Introduction . ....................................................... 2 Systematic Paleontology . ............................................... 3 Superfamily Cynipoidea Latreille . ....................................... 3 -

Hymenoptera: Cynipoidea: Figitidae) of Anthomyiid fl Ies in Conifer Cones

EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF ENTOMOLOGYENTOMOLOGY ISSN (online): 1802-8829 Eur. J. Entomol. 115: 104–111, 2018 http://www.eje.cz doi: 10.14411/eje.2018.008 ORIGINAL ARTICLE The identity of fi gitid parasitoids (Hymenoptera: Cynipoidea: Figitidae) of anthomyiid fl ies in conifer cones MATTIAS FORSHAGE 1 and GÖRAN NORDLANDER 2 1 Swedish Museum of Natural History, Box 50007, 104 05 Stockholm, Sweden; e-mail: [email protected] 2 Department of Ecology, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Box 7044, 750 07 Uppsala, Sweden; e-mail: [email protected] Key words. Hymenoptera, Cynipoidea, Figitidae, Amphithectus, Seitneria, Diptera, Anthomyiidae, Strobilomyia, parasitoid, conifer cones, cone insects, seed orchard, Larix, Picea, taxonomy, new synonymy, new combination Abstract. Larvae of Strobilomyia fl ies (Diptera: Anthomyiidae) are serious pests in conifer-seed orchards because they feed on the seed inside the cones. Figitid parasitoids (Hymenoptera: Cynipoidea) of Strobilomyia larvae in conifer cones are commonly reported but under various generic names. It is argued here that, across the entire Holarctic region, these fi gitids belong to Am- phithectus and perhaps also to Sarothrus (Figitinae), but not to Melanips (Aspicerinae), contrary to some reports. We conclude that the identity of the commonly found fi gitid associated with conifer cones (Larix and Picea) in Europe and Asia is Amphithectus austriacus (Tavares, 1928) comb. n. This is most likely considering the original description and the host association, although the type specimen of Seitneria austriaca Tavares, 1928 is lost. This species name takes priority over the recently described Amphi- thectus coriaceus Paretas-Martinez & Pujade-Villar, 2013. Seitneria Tavares, 1928 becomes a new junior synonym of Amphithec- tus Hartig, 1840, and Amphithectus coriaceus Paretas-Martinez & Pujade-Villar, 2013 becomes a new synonym of Amphithectus austriacus (Tavares, 1928) comb. -

Diptera: Tephritidae and Lonchaeidae

Parasitoid diversity (Hymenoptera: Braconidae and Figitidae) on frugivorous larvae (Diptera: Tephritidae and Lonchaeidae) at Adolpho Ducke Forest Reserve, Central Amazon Region, Manaus, Brazil Costa, SGM.a*, Querino, RB.b*, Ronchi-Teles, B.a*, Penteado-Dias, AMM.c* and Zucchi, RA.d* aCoordenação de Pesquisas em Entomologia, Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas da Amazônia – INPA, Av. André Araújo, 2936, Petrópolis, CP 478, CEP 69011-970, Manaus, AM, Brazil bEmbrapa Roraima, BR 174, Km 8, Distrito Industrial, CEP 69301-970, Boa Vista, RR, Brazil c Departamento de Ecologia e Biologia Evolutiva, Universidade Federal de São Carlos – UFSCar, CP 676, CEP 13565-905, São Carlos, SP, Brazil dEscola Superior de Agricultura “Luiz de Queiroz” – ESALQ, Universidade de São Paulo – USP, Av. Pádua Dias, 11, CEP 13418-900, Piracicaba, SP, Brazil *e-mail: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Received June 25, 2007 – Accepted November 29, 2007 – Distributed May 31, 2009 (With 2 figures) Abstract This study aimed to identify parasitoid species of frugivorous larvae and to describe the tritrophic interactions involv- ing wild fruits, frugivorous insects and their natural enemies at Adolpho Ducke Forest Reserve (RFAD) (Manaus, AM, Brazil). Collections were performed in four 1 km2 quadrants in the corners of the RFAD. The wild fruits were collected inside the forest in access trails leading to each collection area and in trails that surrounded the quadrants, up to five metres from the trail on each side. The fruits were placed in plastic containers covered with thin fabric, with a vermiculite layer on the base to allow the emergence of flies or parasitoids. -

Evolution of the Insects

CY501-C11[407-467].qxd 3/2/05 12:56 PM Page 407 quark11 Quark11:Desktop Folder:CY501-Grimaldi:Quark_files: But, for the point of wisdom, I would choose to Know the mind that stirs Between the wings of Bees and building wasps. –George Eliot, The Spanish Gypsy 11HHymenoptera:ymenoptera: Ants, Bees, and Ants,Other Wasps Bees, and The order Hymenoptera comprises one of the four “hyperdi- various times between the Late Permian and Early Triassic. verse” insectO lineages;ther the others – Diptera, Lepidoptera, Wasps and, Thus, unlike some of the basal holometabolan orders, the of course, Coleoptera – are also holometabolous. Among Hymenoptera have a relatively recent origin, first appearing holometabolans, Hymenoptera is perhaps the most difficult in the Late Triassic. Since the Triassic, the Hymenoptera have to place in a phylogenetic framework, excepting the enig- truly come into their own, having radiated extensively in the matic twisted-wings, order Strepsiptera. Hymenoptera are Jurassic, again in the Cretaceous, and again (within certain morphologically isolated among orders of Holometabola, family-level lineages) during the Tertiary. The hymenopteran consisting of a complex mixture of primitive traits and bauplan, in both structure and function, has been tremen- numerous autapomorphies, leaving little evidence to which dously successful. group they are most closely related. Present evidence indi- While the beetles today boast the largest number of cates that the Holometabola can be organized into two major species among all orders, Hymenoptera may eventually rival lineages: the Coleoptera ϩ Neuropterida and the Panorpida. or even surpass the diversity of coleopterans (Kristensen, It is to the Panorpida that the Hymenoptera appear to be 1999a; Grissell, 1999). -

Superfamily Cynipoidea Family Cynipidae Latreille, 1802

Title Checklist of British and Irish Hymenoptera - Cynipoidea Authors Forshage, M; Bowdrey, J; Broad, G; Spooner, B; van Veen, F Date Submitted 2018-06 Superfamily Cynipoidea The family and subfamily level classification follow Ronquist (1999). Authorship is as follows: Cynipidae – J.P. Bowdrey & B.M. Spooner Figitidae – M. Forshage, G.R. Broad & F. Van Veen Ibaliidae – G.R. Broad Synonymy for Cynipidae is mainly restricted to the better known names and all those that have appeared in the British literature. For additional synonymy see Melika (2006). It should be born in mind that future molecular studies may change our understanding of some species concepts and their alternating generations. Distribution data for Cynpidae are mainly derived by JPB from published sources, but thanks are due to the following for supplying additional data: Janet Boyd, Records Data Manager, British Plant Gall Society; Adrian Fowles, Countryside Council for Wales; Kate Hawkins, Manx Natural Heritage; David Notton, Natural History Museum, London; Mark Pavett, National Museum of Wales; (all pers. comm.). Family Cynipidae Latreille, 18021 Tribe AULACIDEINI Nieves-Aldrey, 19942 AULACIDEA Ashmead, 1897 PSEUDAULAX Ashmead, 1903 follioti Barbotin, 1972 E added by Bowdrey (1994). hieracii (Linnaeus, 1758, Cynips) E S W hieracii (Bouché, 1834, Cynips) sabaudi Hartig, 1840, Aylax graminis Cameron, 1875, Aulax artemisiae (Thomson, 1877, Aulax) crassinervis (Thomson, 1877, Aulax) foveigera (Thomson, 1877, Aulax) nibletti Quinlan & Askew, 1969 S pilosellae (Kieffer, 1901, -

Register Anonymus

© Biologiezentrum Linz/Austria; download unter www.biologiezentrum.at Register Aufgenommen wurden nur im Text (ohne Literaturzitate) vorkommende Stichwörter. Fett gesetzte Ziffern ver- weisen auf eine Abbildung und/oder einen thematischen Schwerpunkt. f. – Seite und folgende, ff. – Seite und zwei folgende Seiten. Index der Krankheiten und krankheitsrelevanter (nosologischer, infektiologischer und epidemiologischer) Stichwörter. 861 Index der Trivialnamen . 867 Index der Viren. 872 Index der wissenschaftlichen Gattungsnamen und der Namen höherer Kategorien (Bakterien, Protozoen, Pilze, Metazoen, Pflanzen) . 873 Liste der Bi- und Trinomina. 883 Index der Krankheiten und krankheitsrelevanter (nosologischer, infektiologischer und epidemiologischer) Stichwörter Abgeschlagenheit 491, 515, 525, 531, 551, Amöbenruhr (Amöbose) 22 572, 588, 728 562, 576, 582, 585, 631, 728 Anämie 129, 202, 264, 334, 388, 448, 497, Arabisches Hämorrhagisches Fieber 478-481 Abort 253f., 545f., 548, 596ff., 603, 608, 819 590, 651, 657, 675f., 687 Araneismus 323 Abszess(bildung) 133, 183, 220, 229, 615, Anaphylaktischer Schock 238, 307, 358, 382, Arbovirus-Infektion 25f., 457-465, 478, 504, 766, 788f., 798 384, 388f., 393ff., 397, 400, 402, 405f. 512, 515, 521, 531, 556 Acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans 105, Anaphylaxie 230, 263, 383, 388, 390, 395, Arrhythmie 536, 657 607, 614, 617f., 620, 622 398, 400, 403, 406 Arthralgie 102, 251, 464, 496, 516ff., 520, Adenolymphadenitis (ADL) 769 Anaplasmose 587, 589-591 582, 770f., 798 Adiadochokinese 541 Aneurysma 668 Arthritis -

New Records of Leptopilina, Ganaspis, and Asobara Species Associated with Drosophila Suzukii in North America, Including Detections of L

JHR 78: 1–17 (2020) Parasitoids of Drosophila suzukii in British Columbia 1 doi: 10.3897/jhr.78.55026 RESEARCH ARTICLE http://jhr.pensoft.net New records of Leptopilina, Ganaspis, and Asobara species associated with Drosophila suzukii in North America, including detections of L. japonica and G. brasiliensis Paul K. Abram1,2,3, Audrey E. McPherson2, Robert Kula4, Tracy Hueppelsheuser5, Jason Thiessen1, Steve J. Perlman2, Caitlin I. Curtis2, Jessica L. Fraser2, Jordan Tam3, Juli Carrillo3, Michael Gates4, Sonja Scheffer5, Matthew Lewis5, Matthew Buffington5 1 Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, Agassiz Research and Development Centre, Agassiz, British Columbia, Canada 2 University of Victoria, Department of Biology, Victoria, British Columbia, Canada 3 The University of British Columbia, Faculty of Land and Food Systems, Vancouver, British Columbia, Unceded xʷməθkʷəy̓ əm Musqueam Territory, Canada 4 Systematic Entomology Laboratory, USDA-ARS, c/o National Museum of Na- tural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., USA 5 British Columbia Ministry of Agriculture, Plant Health Unit, Abbotsford, British Columbia, Canada Corresponding author: Paul K. Abram ([email protected]) Academic editor: Gavin Broad | Received 2 June 2020 | Accepted 24 July 2020 | Published 31 August 2020 http://zoobank.org/45F6DB8A-F429-4E2F-B863-D1A9049710AA Citation: Abram PK, McPherson AE, Kula R, Hueppelsheuser T, Thiessen J, Perlman SJ, Curtis CI, Fraser JL, Tam J, Carrillo J, Gates M, Scheffer S, Lewis M, Buffington M (2020) New records Leptopilinaof , Ganaspis, and Asobara species associated with Drosophila suzukii in North America, including detections of L. japonica and G. brasiliensis. Journal of Hymenoptera Research 78: 1–17. https://doi.org/10.3897/jhr.78.55026 Abstract We report the presence of two Asian species of larval parasitoids of spotted wing Drosophila, Drosophila suzukii (Matsumura) (Diptera: Drosophilidae), in northwestern North America. -

ISH and That Revising (Half) the Nematinae (Tenthredinidae) of The

Hamuli The Newsletter of the International Society of Hymenopterists volume 4, issue 2 20 August 2013 In this issue... Revising Nematinae (STING) 1 ISH and that (Heraty) 1 Webmaster update (Seltmann) 6 News from the Albany Museum (Gess) 7 Challenges of large-scale taxonomy (Whitfield) 8 Hymenoptera Emporium (Sharkey) 9 Rearing Eois in Panama (Parks) 10 Relying on catalogues (Broad) 11 Wasps on the phone (Broad) 12 Hidden terrors (Heraty et al.) 14 Orasema: facts and request (Heraty) 15 Tiny hymys (Sharkey) 16 Fig. 1 Tenthredo arctica (Thomson, 1870) Abisko: Mt. Njullá above Neotropical hym course (Sharkey) 17 treeline (Sweden: Norrbottens Län); 900 m. 05.07.2012 I Encontro Internacional Sobre Vespas (Carpenter) 17 Small trick for lighting (Mikó) 18 Revising (half) the Nematinae What is fluorescing? (Mikó & Deans) 19 Hymenoptera at the Frost (Deans) 22 (Tenthredinidae) of the West Postgraduate corner (Kittel) 24 Palaearctic Paper wasps get official respect (Starr) 24 By: STI Nematinae Group (STING): Andrew D. Liston, Marko Membership information 25 Prous, Stephan M. Blank, Andreas Taeger, Senckenberg Deutsches Entomologisches Institut, Müncheberg, Germany; Erik Heibo, Lierskogen, Norway; Hege Vårdal, Swedish Mu- seum of Natural History, Stockholm, Sweden. ISH and That The Swedish Taxonomy Initiative (STI) has set the goal By: John Heraty, University of California, Riverside, USA of documenting all the estimated 60,000 multicellular species in Sweden (Miller, 2005). One of the STI projects Since I began in this field, there were three things that which recently received funding from the Swedish govern- vastly changed how all of us (behaviorists and systematics) ment is “The Swedish Nematinae (Hymenoptera, Tenth- operate. -

Species List

The species collected in all Malaise traps are listed below. They are organized by group and are listed in the order of the 'Species Image Library'. 'New' refers to species that are brand new to our DNA barcode library. 'Rare' refers to species that were only collected in one trap out of all 64 that were deployed for the program. BIN Group (Scientific Name) Species Common Name Scientific Name New Rare BOLD:AAB0090 Spiders (Araneae) Grass spider Agelenopsis utahana BOLD:AAB5726 Spiders (Araneae) Grass spider Agelenopsis BOLD:AAP2428 Spiders (Araneae) Ghost spider Anyphaena aperta BOLD:AAC6924 Spiders (Araneae) Ghost spider Wulfila saltabundus BOLD:AAD7855 Spiders (Araneae) Starbellied orbweaver Acanthepeira stellata BOLD:AAA4125 Spiders (Araneae) European garden spider Araneus diadematus BOLD:AAA8399 Spiders (Araneae) Six-spotted orb weaver Araniella displicata BOLD:AAN4894 Spiders (Araneae) Six-spotted orb weaver Araniella displicata BOLD:ACY1317 Spiders (Araneae) Humpbacked orb weaver Eustala anastera BOLD:AAA8999 Spiders (Araneae) Furrow orbweaver Larinioides cornutus BOLD:AAA3681 Spiders (Araneae) Furrow spider Larinioides patagiatus BOLD:AAB7330 Spiders (Araneae) Orb weaver Mangora gibberosa BOLD:AAA4123 Spiders (Araneae) Arabesque orbweaver Neoscona arabesca BOLD:AAD1564 Spiders (Araneae) Leafcurling sac spider Clubiona abboti BOLD:AAP3591 Spiders (Araneae) Leafcurling sac spider Clubiona moesta BOLD:AAD5417 Spiders (Araneae) Leafcurling sac spider Clubiona obesa BOLD:AAI4087 Spiders (Araneae) Leafcurling sac spider Clubiona