Year VII Volume 10/2020 the Roaring (20)20

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Coining of Words in Manipuri

International Journal of Latest Research in Humanities and Social Science (IJLRHSS) Volume 02 - Issue 12, 2019 www.ijlrhss.com || PP. 93-99 Coining of Words in Manipuri Mayengbam Bidyarani Devi, Ph.D. Senior Fellow, ICSSR Department of Linguistics, Manipur University, Canchipur, Manipur, India Abstract: The present paper contributes to the study of Coining of words in Manipuri, a Tibeto-Burman language. Coining of words in Manipuri is the creation or invention of new words or phrases in which they are formed for a new semantic representation. This creation of new words helps a language to develop new technologies. Manipuri has a good numbers of coined words in their lexicon. Most of the coined words seem to have been created to fill a lexical gap for new objects that were introduced to Manipuri speakers. Coining of words is mostly found in local daily newspapers, journals, literature, media and day today conversation. The best way to coin a new word in Manipuri is to describe an object or a phenomenon. New coin words which are predominantly reflect the social, political, economical and cultural changes. Most of coined words in Manipuri are in the field of literature and conversations. Many of the coined words exist for a long time while some of them survive only for a short period. Coining of words will enrich the lexical development in Manipuri. Keywords: Coining, social, cultural, vocabulary and lexical 1. Introduction Neologisms are newly coined terms, words, or phrases that may be commonly used in everyday life but have yet to be formally accepted as constituting mainstream language. -

Statewide Events Bring in Over $120K to HIV/AIDS

VOL.1839 FREE MICHIGAN’S LGBT NEWS SOURCE SINCE 1993 PRIDESOURCE.COM SEPT. 30, 2010 Michigan Walks! Statewide events bring in over $120K to HIV/AIDS ADAM LEVINE KALEIDOSCOPE COX: PRO PROP. 8 Maroon 5 frontman Ruth Ellis event AG adds Michigan to talks new album honors youth, dance anti-gay marriage brief Sept. 30, 2010 Vol. 1839 • Issue 681 Publishers Susan Horowitz Jan Stevenson EDITORIAL Editor in Chief Susan Horowitz Entertainment Editor Chris Azzopardi Associate News Editor Jessica Carreras 12 17 21 33 Arts & Theater Editor Donald V. Calamia 12 Obama heckled at Contributing Writers News Life Charles Alexander, Paul Berg, fundraiser – again Wayne Besen, D.A. Blackburn, HIV, gay rights advocates cite ‘broken Dave Brousseau, Michelle E. Brown, 5 Between Ourselves 17 All Over Adam Levine John Corvino, Jack Fertig, Emily Brown promises’ at N.Y. event Maroon 5 frontman on new album, bedroom Joan Hilty, Lucy Hough, Lisa Keen, Jim Larkin, Anthony Paull, behavior and being so cool with the queers Crystal Proxmire, Bob Roehr, 6 Michigan Walks! 13 Judge orders lesbian Gregg Shapiro, Jody Valley, Detroit chapter of statewide HIV/AIDS services reinstated to Air Force D’Anne Witkowski, Imani Williams 20 Hear Me Out Rex Wockner, Dan Woog fundraisers sees 450 attendees, $28K raised Senate filibuster of DADT repeal combats with KT Tunstall roars back with “Tiger Suit.” Plus: two pro-gay court rulings Maroon 5 stays safe with latest Contributing Photographers Andrew Potter 6 44 percent of gay, bisexual Emily Locklear men with HIV don’t know it 13 “Don’t -

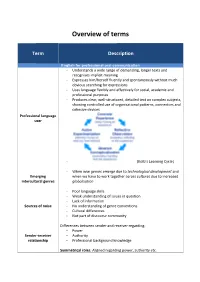

Overview of Terms

Overview of terms Term Description English for professional oral communication - Understands a wide range of demanding, longer texts and recognises implicit meaning - Expresses him/herself fluently and spontaneously without much obvious searching for expressions - Uses language flexibly and effectively for social, academic and professional purposes - Produces clear, well-structured, detailed text on complex subjects, showing controlled use of organisational patterns, connectors and cohesive devices Professional language user - (Kolb’s Learning Cycle) - When new genres emerge due to technological development and Emerging when we have to work together across cultures due to increased intercultural genres globalisation - Poor language skills - Weak understanding of issues in question - Lack of information Sources of noise - No understanding of genre conventions - Cultural differences - Not part of discourse community Differences between sender and receiver regarding: • Power Sender-receiver • Authority relationship • Professional background knowledge Symmetrical roles: Aligned regarding power, authority etc. Asymmetrical roles: Not aligned Static relationship status or dynamic relationship status Oral communicative competence Understanding, explaining and using language correctly (:grammar, Linguistic vocabulary, intonation) Correctness and oral fluency are not tested in this competence exam! Understanding, explaining and using language in a context (:use of speech Discourse and text acts, genre conventions, fillers and gambits, cohesion -

Die Entwicklung Der Item-Tänze Im Bollywood-Kino

DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit „Die Entwicklung der Item-Tänze im Bollywood-Kino im Hinblick auf die Rolle der Frau“ verfasst von Miriam Rubey angestrebter akademischer Grad Magistra der Philosophie (Mag.phil.) Wien, 2015 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 317 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Diplomstudium Theater-, Film- und Medienwissenschaft Betreuerin: Univ.-Prof. Mag. Dr. Annette Storr Inhaltsverzeichnis Inhaltsverzeichnis .................................................................................................... 2 1 Einleitung und Fragestellung ........................................................................... 4 2 Einführung in die Bollywood Item-Songs von 1993-2014 .............................. 7 3 Die Bedeutung des Tanzes im Hindifilm ........................................................12 3.1 Verkörperungen/Ausführungsformen im Bollywoodtanz ......................................... 19 3.2 Der indische Tanz: von Klassik bis Moderne .......................................................... 23 3.3 Die Rolle der Tänzerin in Indien ............................................................................. 29 3.4 Die Rezeption von Bollywoodfilmen und deren Tänzen .......................................... 32 4 Sexualität in den Bollywoodfilmen .................................................................35 4.1 Die Rolle der Kamera im Item-Tanz und wie diese die Frau inszeniert ................... 37 4.2 Der „male-gaze“ .................................................................................................... -

CMS.603 / CMS.995 American Soap Operas Spring 2008

MIT OpenCourseWare http://ocw.mit.edu CMS.603 / CMS.995 American Soap Operas Spring 2008 For information about citing these materials or our Terms of Use, visit: http://ocw.mit.edu/terms. SOAP OPERAS AND TEEN DRAMAS KATHARINE CHU 1. Introduction Since soap operas peaked in popularity in the eighties, there has been a steady decline in ratings. While there are many reasons and possibilities as to why soap operas have dramatically dropped in popularity and while many scholars attribute soap opera decline in the mid-nineties to the OJ Simpson trial, soap operas ratings took another hit in the late nineties (Ford, As the World Turns in a Convergence Culture, 43). There are many possibilities for this decline; for the purposes for this paper, I would like to closely examine one of the reasons that may have caused the decline of the U.S. soap opera is the rise of the teen drama. Soaps have often had an unproportionally large teenage fan base. In the mid-1990s over 17% of soap fans were between 18-24 years olds, even though this demographic is only around 13% of the general population (Liccardo, Who Really Watches the Daytime Soap? ). According to books like Harrington and Bielby’s Soap Fans, when soap opera fans are asked when they started watching soap operas, many of them responded that they became hooked as teenagers and have been following characters ever since on their favorite soaps (10). This did not resonate with me because, as a teenager in the late nineties, I did not watch soap operas, nor did any of my friends. -

CMS.603 American Soap Operas

MIT OpenCourseWare http://ocw.mit.edu CMS.603 American Soap Operas Spring 2008 For information about citing these materials or our Terms of Use, visit: http://ocw.mit.edu/terms. As the World Turns in a Convergence Culture by Samuel Earl Ford B.A. English, Mass Communication, News/Editorial Journalism, Communication Studies Western Kentucky University, 2005 SUBMITTED TO THE PROGRAM IN COMPARATIVE MEDIA STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN COMPARATIVE MEDIA STUDIES AT THE MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY JUNE 2007 2007 Samuel Earl Ford. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Signature of Author: ____________________________________________________________ Program in Comparative Media Studies 11 May 2007 Certified by: ___________________________________________________________________ William Charles Uricchio Professor of Comparative Media Studies Co-Director, Comparative Media Studies Thesis Supervisor Accepted by: __________________________________________________________________ Henry Jenkins Peter de Florez Professor of Humanities Professor of Comparative Media Studies and Literature Co-Director, Comparative Media Studies 1 As the World Turns in a Convergence Culture by Samuel Earl Ford Submitted to the Program in Comparative Media Studies on May 11, 2007, in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Comparative Media Studies ABSTRACT The American daytime serial drama is among the oldest television genres and remains a vital part of the television lineup for ABC and CBS as what this thesis calls an immersive story world. However, many within the television industry are now predicting that the genre will fade into obscurity after two decades of declining ratings. -

Worst Words of the Decade Longlist 22 December 2020.Docx

Media release 22 December 2020 “Alternative facts” named Worst Words of the Decade Plain English Foundation has voted alternative facts as its worst word or phrase of the decade. The now infamous phrase from the Trump administration stood out in a post-truth period when global politics took an Orwellian turn. “Politicians are known for obfuscation, but ‘alternative facts’ was particularly worrying,” said the Foundation’s Executive Director, Dr Neil James. “It suggests our elected leaders can be right even when they are factually wrong. That sets a dangerous precedent for democracy.” Since 2010, Plain English Foundation has curated an annual list of the worst words and phrases to highlight the importance of clear public language. Political spin had a constant presence on these lists, from freedom gas and efficiency dividend to efforting outreach and high value targeting. Corporate doublespeak was equally hard to avoid. Orica and Volkswagen took Worst Words titles when they tried to paper over pollution. Orica referred to chemical leaks as fugitive emissions while Volkswagen hid behind possible emissions non-compliance when it cheated on environmental tests. The notable corporate trend of the decade was the way corporations spoke about job cuts when they had to fire staff. Instead, thousands of workers were demised or disestablished or subjected to repositioning actions. One was even offered external career development opportunities. Business was also represented each year by new buzzwords. Although none of these took the top prize, jargon such as thought shower, collabition, frictionless and strategic staircase was a constant on our worst words lists. The decade also spawned an impressive collection of Frankenwords, as brands vied to attract consumer attention. -

Magazine Media

DECEMBER ISSUE: FILM M M MediaMagazine eediadia agazine Menglish and media centre issue 26 | decemberM 2008 GGloballobal ffilmilm ccollaborationollaboration SStarstars WWaltzaltz wwithith BBashirashir NNoiroir & tthehe ccityity SShockinghocking ccinemainema english and media centre andmedia english SShanehane MMeadowseadows | issue 26 | december 2008 26|december | issue MM MM MediaMagazine is published by the English and article ‘Enter the Dragon’ is an essential and fact- Media Centre, a non-profit making organisation. packed read – look no further for an introduction The Centre publishes a wide range of classroom editorial to the cinema industries of South-East Asia. materials and runs courses for teachers. If Welcome back to MediaMag and our special All that should keep you busy over the you’re studying English at A Level, look out for Film issue – and if you’re wondering why we’re Christmas holidays ... But if you’ve got time on emagazine, also published by the Centre. not imbued with the seasonal festive spirit it’s your hands (ha!) sneak a visit to our amazing new feature: MediaMagClips, where you can The English and Media Centre because we’re bulging at the seams with cinema- view video soundbites on key concepts from 18 Compton Terrace related goodies. the great and the good in Media Studies (www. London N1 2UN Star studies and issues of representation mediamagazine.org.uk). Telephone: 020 7359 8080 are two of the major debates running through Fax: 020 7354 0133 this edition. Elaine Homer’s excellent overview Email for subscription enquiries: of critical approaches to the phenomenon of Next up: MediaMag 27 – [email protected] stardom should be a gift for Film students. -

Elana Levine 1 Curriculum Vitae Elana Levine [email protected]

Elana Levine 1 Curriculum Vitae Elana Levine [email protected] Media, Cinema, and Digital Studies Department of English University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Curtin Hall 483 Milwaukee, WI 53211 Education Ph.D., Communication Arts, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 2002 M.A., Communication Arts, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 1997 B.A., Telecommunications and English, Indiana University, 1992 Academic Positions Professor, Department of English, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2019-present; Department of Journalism, Advertising, and Media Studies, 2016-2019 Associate Professor, Department of Journalism, Advertising, and Media Studies (formerly Journalism and Mass Communication), University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2008-2016 Assistant Professor, Department of Journalism and Mass Communication, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2002-2008 Research Books Her Stories: Daytime Soap Opera and US Television History, Durham: Duke University Press, 2020 Cupcakes, Pinterest, Ladyporn: Feminized Popular Culture in the Early 21st Century, editor. Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2015 Legitimating Television: Media Convergence and Cultural Status, with Michael Z. Newman. New York: Routledge, 2012 Undead TV: Essays on Buffy the Vampire Slayer, co-editor with Lisa Parks. Durham: Duke University Press, 2007 Wallowing in Sex: The New Sexual Culture of 1970s American Television. Durham: Duke University Press, 2007 Elana Levine 2 Articles in Refereed Journals “Love in the Afternoon: The Supercouples of 1980s Daytime Soap Opera,” Critical Studies in -

Questions 5.29.16

Small Group Questions May 29 | Selectivity Getting Started: The Warm Up (10 min.) Biblical Passage: Proverbs 27:17 “As iron sharpens iron, so one man sharpens another.” Suppor;ng Scriptures: John 13:34 … “A new command” 2 Corinthians 6:14-16, 7:1 ... “be careful with your matchups” Luke 8:5-8 … “sow on good soil” Proverbs 17:17...”a friend loves at all ;mes” Proverbs 18:24 ... “an enduring friendship” The Big Idea: There are NO neutral rela;onships. Each one, whether personal, professional, casual or in;mate, influences your life. They either dull you or make you sharper. They have the capacity to make your life beIer or to usher you into a miserable existence. The Warm Up Ques;ons: 1. Have some fun picking “supercouple” nicknames for those in your group. 2. Share your longest running friendship and why it stands the test of ;me. 3. What’s your best quality as a friend? Resetting: Rethinking the Message (15 min.) Your heard about the “Law of Selec;vity” as it relates to choosing friends. 1. Two types of love, Agapao and Agape, were highlighted so discuss the meaning of each. a. Agapao: To receive people with hospitality… to greet them well. (humanitarian) Small Group Questions May 29 | Selectivity b. Agape: Sacrificial love…. Without expec;ng anything in return. (Divine) 2. Do you find it hard to dis;nguish between the two when selec;ng friends? 3. Discuss how well, or how poorly, do you discern the character of others? Dig-In: Beyond the Message (20 min.) Suppor@ng Passages: Read Jeremiah 29:11 within the context of how friends can influence the purpose God has laid before you: Jodie men;oned 5 valuable traits that characterize friends that can help you carry out your God given purpose: 1. -

You Are Being Lied To

1 This anthology © 2001 The Disinformation Company Ltd. All of the articles in this book are © 1992-2000 by their respective authors and/or original publishers, except as specified herein, and we note and thank them for their kind permission. Published by The Disinformation Company Ltd., a member of the Razorfish Subnetwork 419 Lafayette Street, 4th Floor New York, NY10003 Tel: 212.473.1125 Fax: 212.634.4316 www.disinfo.com Editor: Russ Kick Design and Production: Tomo Makiura and Paul Pollard First Printing March 2001 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a database or other retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, by any means now existing or later discovered, including without limitation mechanical, electronic, photographic or other- wise, without the express prior written permission of the publisher. Library of Congress Card Number: 00-109281 ISBN 0-9664100-7-6 Printed in Hong Kong by Oceanic Graphic Printing Distributed by Consortium Book Sales and Distribution 1045 Westgate Drive, Suite 90 St. Paul, MN 55114 Toll Free: 800.283.3572 Tel: 651.221.9035 Fax: 651.221.0124 www.cbsd.com Disinformation is a registered trademark of The Disinformation Company Ltd. The opinions and statements made in this book are those of the authors concerned. The Disinformation Company Ltd. has not verified and neither confirms nor denies any of the foregoing. The reader is encouraged to keep an open mind and to independently judge for him- or herself whether or not he or she is being lied to. The Disinform a tion Guide to Media Distorti o n , Hi s t o r i c a l Whi t e washes and Cultural Myths Edited by Russ Kick ACKNOWLEDGMENTS To Anne Marie, who restored my faith in the truth. -

1 Soap Operas and the History of Fan Discussion Sam Ford This Essay

Soap Operas and the History of Fan Discussion Sam Ford This essay examines the ways in which fans have found ways to express themselves and form communities surrounding soap opera texts, starting with one-on-one localized discussions with fans and through more proactive responses such as fan mail and fan clubs. The study also focuses on the lack of coverage on soaps and room for publishing the voices of soap opera fans in the popular press and how the soap opera press eventually filled that niche. It concludes with an in-depth look at online fan communities surrounding soap operas and how they have been and might be understood, encouraging an emphasis on valuing the vernacular theory of the fan community and paying more attention to the various ways that online fans interact with the text and one another. Soap Opera and Fan Discussion Soaps do not exist in a vacuum, and the show’s daily texts can only be completely understood in the context of the community of fans surrounding them. Instead of imagining the audience as a passive sea of eyeballs measured through impressions, this approach views soap operas as the central piece and catalyst for a social network of fans. Acting as dynamic social texts, soap operas are created as much by the audience that debates, critiques, and interprets them than through the production team itself.1 This collective attribution of meaning has been proven to be a strong motivation for viewing the show, whether those discussions take place in conversations between families while the show is on, post-“story” phone calls among friends and relatives, or else at the workplace or on soaps discussion boards.