Oregon State Bar Association

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Charitable Company Match List

The Aloha Lacrosse Club is an IRS 501(c)3 non-profit organization. This means that your financial or property donation is 100% tax deductible! There are also many companies in the Beaverton/Portland area that will match an employee's contribution. Please check with your HR department regarding your companies policy to matching your donations! Local Companies that Match Employee's Charitable Contributions Abbott Laboratories GlaxoSmithKline Foundation Paccess Supply Chain Solutions ABR, Inc. GlobalGiving Pacific Power Foundation ACE Foundation Matching Gift Program Global Standards, LLC Piper Jaffary Foundation Ada County Association of Realtors Foundation Portland General Electric ADP Hanna Andersson Portland Trail Blazers Aetna Hewlett-Packard Pepsi Bottling Group Alaska Airlines H. J. Heinz/Ore-Ida Company Foundation PPG Industries Foundation Albertson’s, Inc. Hunter-Davisson, Inc. Allendale Insurance Home Depot Matching Gifts Quest Diagnostics Allstate Houghton Mifflin Matching Gifts Qwest Communications Foundation Altria Employee Involvement Program HSBC Bank USA, N.A. Amgen Regence BlueCross BlueShield of Oregon American Express Intermountain Gas Industries Foundation Rejuvenation, Inc American Honda Motor Company, Inc. Intel REI Ameriprise IBM International Foundation Matching Grants Rockwell Collins Corporation Ames Planning Associates, Inc. Insurance Services Office, Inc. Aon Foundation Matching Gift Program SAP Apple John Hancock Financial Services Sara Lee Foundation Applied Materials Johnson & Johnson Family of Companies S.D. Deacon Corp. Ares Operations, LLC Johnson Controls Foundation Shell Oil Company Arkema Group Starbucks Coffee AT&T Foundation Matching Gifts Center Key Bank Synopsys Autodesk, Inc Kaiser Permanente Matching Gifts Saint-Gobain Corporation Foundation Kaplan, Inc. SBC Foundation Bank of America KPMG Sprint Foundation Bank Of The West SRG Partnership Becker Capital Management Laika Standard Insurance Bechtel Legacy Health System Stockamp & Associates Benjamin Moore & Co. -

Ferroelectric Hysteresis Measurement & Analysis

NPL Report CMMT(A) 152 Ferroelectric Hysteresis Measurement & Analysis M. Stewart & M. G. Cain National Physical Laboratory D. A. Hall University of Manchester May 1999 Ferroelectric Hysteresis Measurement & Analysis M. Stewart & M. G. Cain Centre for Materials Measurement and Technology National Physical Laboratory Teddington, Middlesex, TW11 0LW, UK. D. A. Hall Manchester Materials Science Centre University of Manchester and UMIST Manchester, M1 7HS, UK. Summary It has become increasingly important to characterise the performance of piezoelectric materials under conditions relevant to their application. Piezoelectric materials are being operated at ever increasing stresses, either for high power acoustic generation or high load/stress actuation, for example. Thus, measurements of properties such as, permittivity (capacitance), dielectric loss, and piezoelectric displacement at high driving voltages are required, which can be used either in device design or materials processing to enable the production of an enhanced, more competitive product. Techniques used to measure these properties have been developed during the DTI funded CAM7 programme and this report aims to enable a user to set up one of these facilities, namely a polarisation hysteresis loop measurement system. The report describes the technique, some example hardware implementations, and the software algorithms used to perform the measurements. A version of the software is included which, although does not allow control of experimental equipment, does include all the analysis features and will allow analysis of data captured independently. ã Crown copyright 1999 Reproduced by permission of the Controller of HMSO ISSN 1368-6550 May 1999 National Physical Laboratory Teddington, Middlesex, United Kingdom, TW11 0LW Extracts from this report may be reproduced provided the source is acknowledged. -

2010 Alumni and Business Partner Awards

2010 ALUMNI AND BUSINESS PARTNER AWARDS THURSDAY, MAY 6, 2010 THE GOVERNOR HOTEL — PORTLAND Hit the ground running. Intensive. Innovative. Integrated. Whether you are a continuing student or working professional, Oregon State University’s Master of Business Administration prepares you for the challenges of today’s global marketplace. Through experiential learning, you’ll cultivate an entrepreneurial mindset that emphasizes social responsibility, sustainability, and ethics. Complete your degree in as little as nine months. Evening classes available. Global Top 100 www.bus.oregonstate.edu 2 OSU College of Business 2010 Alumni and Business Partner Awards A word from OSU President Ed Ray By Edward J. Ray, President Brown, who retired from a tre- the many reasons why the college that emphasize experiential learn- Oregon State University mendously successful career as a continues to grow in size, impact ing and for students who graduate PricewaterhouseCoopers partner and reputation. Enrollment last prepared to make a difference, Oregon State University has and now teaches at OSU as an fall included 2,327 undergraduate the college is now on the cusp of always been a place with a pur- Executive in Residence—embody and graduate students, compared a bold and exciting new era. As pose—that of making a measure- the very best of Oregon State. Their to 1,775 just ten years ago. Like state and business leaders look able difference in the lives and professional contributions and the rest of our university, the col- with growing consistency to our communities -

Companies with Matching Gift Programs

Companies with Matching Gift Programs Many companies encourage charitable giving by matching gifts made by their employees. As a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization, CHCA is eligible for matching gifts. Below is a list of companies that have matching gift programs. Even if a company is not listed, they may still have a matching gift program. In addition, not all companies match PK-12 schools. To find out if your company matches gifts made to CHCA, please contact your HR representative. If you need additional assistance, please e-mail Paige Tomlin at [email protected]. A AK Steel 3Com Corporation Albemarle Corp. 3M Company Alco Standard AlliedSignal Inc. Alexander and Baldwin Inc. Allstate Alexander Hamilton Life Abacus Capital Investments Alexander Haas Martin and Partners Abbott Laboratories Al Neyer Altera Corp. Contributions Allegro Microsystems Inc. Accenture Alliance Bernstein Access Fund Alliance Capital Management L.P. ACE INA Foundation Alliance Coal LLC Adams Harkness and Hill Inc. Alliant Techsystems Altria Group Allegiance Corp. and Baxter International Adaptec Foundation Allendale Insurance Foundation AMBAC Indemnity American Natl Bank & Trust ADC Telecommunications American Intl Group, Inc. AMD Corporate Giving American Standard Found Adobe Systems Inc. Amgen Inc. ADP Foundation AMN Healthcare Services American Express Co. AmSouth BanCorp. A & E Television Networks American Stock Exchange AEGON TRANSAMERICA Ameriprise Financial AEP Ameritech Corp. AES Corporation AMETEK / Sealtron A.E. Staley Manufacturing Co. AMSTED Industries Inc. American Fidelity Corp. Amylin Pharmaceuticals Aetna Foundation, Inc. Anadarko Petroleum Corp. American General Corp. Analytics Operations Engineering AG Communications Systems Analog Devices Inc. American Honda Motor Co. Avon Products Foundation, Inc. -

Service Manual TDS 520B, 540B, 620B, TDS 644B, TDS 680B, TDS 684B, TDS 724A, TDS 744A, & TDS 784A Digitizing Oscilloscope 07

Service Manual TDS 520B, 540B, 620B, TDS 644B, TDS 680B, TDS 684B, TDS 724A, TDS 744A, & TDS 784A Digitizing Oscilloscope 070-9386-03 Warning The servicing instructions are for use by qualified personnel only. To avoid personal injury, do not perform any servicing unless you are qualified to do so. Refer to the Safety Summary prior to performing service. Copyright E Tektronix, Inc. All rights reserved. Tektronix products are covered by U.S. and foreign patents, issued and pending. Information in this publication supercedes that in all previously published material. Specifications and price change privileges reserved. Printed in the U.S.A. Tektronix, Inc., P.O. Box 1000, Wilsonville, OR 97070–1000 TEKTRONIX and TEK are registered trademarks of Tektronix, Inc. WARRANTY Tektronix warrants that this product will be free from defects in materials and workmanship for a period of three (3) years from the date of shipment. If any such product proves defective during this warranty period, Tektronix, at its option, either will repair the defective product without charge for parts and labor, or will provide a replacement in exchange for the defective product. In order to obtain service under this warranty, Customer must notify Tektronix of the defect before the expiration of the warranty period and make suitable arrangements for the performance of service. Customer shall be responsible for packaging and shipping the defective product to the service center designated by Tektronix, with shipping charges prepaid. Tektronix shall pay for the return of the product to Customer if the shipment is to a location within the country in which the Tektronix service center is located. -

Vanport Society

DONOR HONOR ROLL 2014-2015 | Recognizes gifts received between July 1, 2014 through June 30, 2015. Earle Chiles William Michael Foster Family Phil Bogue VANPORT Sue Cooley Friends from Indonesia Duncan and Cindy Campbell Jeannine Cowles Gerding Edlen Development Norm and Rickie Daniels SOCIETY Michael DeShane ◊ and Keren Brown Wilson ◊ John and Betty Gray Geography Fund of the Laura and Doug Eyer Mark and Ann Edlen Oregon Community Foundation Les and Nancy Fahey Diana Gerding Conrad N. Hilton Foundation Tom and Marilyn Fink The Vanport Society recognizes Terry Harrington Howard Hughes Medical Institute Bill and Jane Furman donors whose lifetime giving to Al and Nancy Jubitz Intel Corporation/Intel Foundation Jack and Deane Garrison Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Portland State University is Irving Levin and Stephanie Fowler Bob Gleason ◊ • W.M. Keck Foundation $100,000 or more. With deep Lawrence Levy and Pamela Lindholm- Levy Dan and Karen Halloran W. K. Kellogg Foundation gratitude, we honor all members Jack and Lynn Loacker Debra C. Harris ◊ The Lemelson Foundation of the Vanport Society. Lorry Lokey Art and Sandy James Bob and Sharon Miller LTX-Credence Phil and Penny Knight Rick and Erika Miller Maybelle Clark Macdonald Fund Davis and Judy Moriuchi Gordon and Betty Moore Mentor Graphics Corporation/Mentor Graphics Bob Rawson Foundation FREMONT MEMBERS Robert and Jane Morrow Julie and William Reiersgaard Meyer Memorial Trust $10 MILLION AND ABOVE Martha and John O’Malley Dick Solomon and Alyce Flitcraft M. J. Murdock Charitable Trust Jim and Shirley Rippey Spike Wadsworth and Sherry Sheng INDIVIDUALS Oracle America, Inc. John Salmon and Marcia Schulmerich Fariborz and Azam Maseeh The Oregon Community Foundation CORPORATIONS, FOUNDATIONS, Allen Ray Sandstrom ORGANIZATIONS The Pew Charitable Trusts CORPORATIONS, FOUNDATIONS, Arlene Schnitzer Anonymous ORGANIZATIONS Portland General Electric Company/PGE Jordan Schnitzer Foundation The Autzen Foundation Massiah Foundation, Inc. -

Company Match List 2020

Employer Matching Company List 3Com Corporation Alco Standard Fdn. 3M Company AlCOA Foundation Abacus Capital Investments Alexander and Baldwin Inc. Abbot Laboratories Alexander and Baldwin Foundation Alexander Haas Martin and Partners Alexander Hamilton Life Accenture Foundation, Inc. Allegro Microsystems Inc. Access Fund Allegiance Corp. and Baxter International Allendale Insurance Foundation Allendale Mutual Insurance Co. AllianceBernstein ACE INA Foundation Alliance Capital Management L.P. Alliance Coal LLC Adams Harkness and Hill Inc. Alliant Techsystems Adaptec Foundation AlliedSignal Inc. ADC Foundation Allstate Foundation, The Allstate Giving Campaign ADC Telecommunications Altera Corp. Contributions Program Adobe Systems Inc. Altria Employee Involvement ADP Foundation Programs A & E Television Networks Altria Group AMBAC Indemnity Corporation AEGON TRANSAMERICA AMD Corporate Giving Program AEP American Express Co AES Corporation American Fidelity Corp. A.E. Staley Manufacturing Co. American General Corp. Aetna Foundation, Inc. American Honda Motor Co. Inc. AG Communications Systems American National Bank and Trust Co. of Chicago Agilent Technologies American Standard Foundation Aid Association for Lutherans American Stock Exchange AIG Matching Grants Program Air Liquide America Corporation Aileen S. Andrew Foundation Air Products and Chemicals Inc. Albemarle Corp. AIM Foundation Ameriprise Financial Ameritech Corp. Amgen Center American Inter Group Amgen Foundation Amgen Inc. Employer Matching Company List American International Group, Inc. Aspect Telecommunications Associates Corp. of North America AMSTED Industries Inc. Astra Merck Inc. AMN Healthcare Services, Inc. AstraZeneca Pharmaceutical LP Atapco Amylin Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Corp. Giving ATK Foundation Program Anadarko Petroleum Corp. Analog Devices Atlantic Data Services Inc. Analytics Operations Engineering Analog Devices Atochem North America Foundation ATOFINA Inc. Chemicals, Inc. Anchor/Russell Capital Advisors Inc. -

Instruction Manual TMS 109A Socket 7 Microprocessor Support 071-0497-01

Instruction Manual TMS 109A Socket 7 Microprocessor Support 071-0497-01 Warning The servicing instructions are for use by qualified personnel only. To avoid personal injury, do not perform any servicing unless you are qualified to do so. Refer to all safety summaries prior to performing service. Copyright E Tektronix, Inc. All rights reserved. Licensed software products are owned by Tektronix or its suppliers and are protected by United States copyright laws and international treaty provisions. Use, duplication, or disclosure by the Government is subject to restrictions as set forth in subparagraph (c)(1)(ii) of the Rights in Technical Data and Computer Software clause at DFARS 252.227-7013, or subparagraphs (c)(1) and (2) of the Commercial Computer Software – Restricted Rights clause at FAR 52.227-19, as applicable. Tektronix products are covered by U.S. and foreign patents, issued and pending. Information in this publication supercedes that in all previously published material. Specifications and price change privileges reserved. Printed in the U.S.A. Tektronix, Inc., P.O. Box 1000, Wilsonville, OR 97070–1000 TEKTRONIX and TEK are registered trademarks of Tektronix, Inc. SOFTWARE WARRANTY Tektronix warrants that the media on which this software product is furnished and the encoding of the programs on the media will be free from defects in materials and workmanship for a period of three (3) months from the date of shipment. If a medium or encoding proves defective during the warranty period, Tektronix will provide a replacement in exchange for the defective medium. Except as to the media on which this software product is furnished, this software product is provided “as is” without warranty of any kind, either express or implied. -

Pulse I-V Characterization of Non-Volatile Memory Technologies –– APPLICATION NOTE Pulse I-V Characterization of Non-Volatile Memory Technologies APPLICATION NOTE

Pulse I-V Characterization of Non-Volatile Memory Technologies –– APPLICATION NOTE Pulse I-V Characterization of Non-Volatile Memory Technologies APPLICATION NOTE Introduction the NVM projects, tests, and parameters for testing floating gate flash, phase-change cell, ferro-electric cell devices, and Until recently, floating gate (FG) NAND flash memory resistive memory. technology has successfully met the growing requirement for non-volatile memory (NVM) for digital cameras, MP3 players and smartphones. However, there is increasing concern in Brief History of NVM the consumer electronics industry that floating gate NVM may Scientists around the world are investigating NVM alternatives not be able to continue providing higher storage capacities at that can replace FG NAND technology, including phase- the ever-lower cost-per-bit requirements that drive the NVM change memory (PCM/PRAM), charge trap flash (CTF/ market [1]. The potential for the floating gate approach to “hit SONOS), resistive memory (ReRAM), ferro-electric memory the wall” means that research into alternative technologies (FeRAM), and magnetoresistive memory (MRAM) (Figure 1). has become increasingly critical. These device technologies have been studied for years, and each is currently available in the market in some form. This wide-ranging research into an expanding number of materials and technologies requires an electrical test system Other NVM technologies, including spin-transfer torque with wide dynamic range and flexible parameter control. (STT) MRAM, floating body (FBRAM), and various types of This application note provides a brief history of NVM, an carbon-nanotube-based memory (CNT RAM), are being overview of the test parameters required for electrical actively researched to determine their suitability for memory characterization of NVM materials and devices, and an product applications. -

Employer Matching Company List 2020

A 3Com Corporation Alco Standard Fdn. 3M Company AlCOA Foundation Abacus Capital Investments Alexander and Baldwin Inc. Abbot Laboratories Alexander and Baldwin Foundation Accenture Foundation, Inc. Allegro Microsystems Inc. Access Fund Allegiance Corp. and Baxter International Alliance ACE INA Foundation Alliance Capital Management L.P. Alliance Coal LLC Allendale Insurance Foundation Allendale Mutual Insurance Co. Adams Harkness and Hill Inc. Alliant Techsystems Adaptec Foundation AlliedSignal Inc. ADC Foundation Allstate Foundation, The Allstate Giving Campaign ADC Telecommunications Altera Corp. Contributions Program Adobe Systems Inc. Altria Employee Involvement ADP Foundation Programs A & E Television Networks Altria Group AMBAC Indemnity Corporation AEGON TRANSAMERICA AMD Corporate Giving Program AEP American Express Co AES Corporation American Fidelity Corp. A.E. Staley Manufacturing Co. American General Corp. Aetna Foundation, Inc. American Honda Motor Co. Inc. AG Communications Systems American National Bank and Trust Co. of Chicago Agilent Technologies American Standard Foundation Aid Association for Lutherans American Stock Exchange AIG Matching Grants Program Air Liquide America Corporation Aileen S. Andrew Foundation Air Products and Chemicals Inc. Albemarle Corp. AIM Foundation Ameriprise Financial Ameritech Corp. Amgen Center American Inter Group Amgen Foundation Amgen Inc. American International Group, Inc. Aspect Telecommunications Associates Corp. of North America AMSTED Industries Inc. Astra Merck Inc. AMN Healthcare Services, Inc. AstraZeneca Pharmaceutical LP Atapco Amylin Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Corp. Giving Program ATK Foundation Analog Devices Atlantic Data Services Inc. Analytics Operations Engineering Analog Devices Inc. Atochem North America Foundation ATOFINA Chemicals, Inc. Anchor/Russell Capital Advisors Inc. Andersons Inc. ATO FINA Pharmaceutical Foundation AT &T Andrea Frankel Allen Charities Anheuser-Busch Foundation AT&T Communications Systems AT&T Foundation AOL Time Warner Foundation Autodesk Inc. -

Instruction Manual TSG 120 YC / NTSC Signal Generator S/N B020765 and Above 070-8003-02

Instruction Manual TSG 120 YC / NTSC Signal Generator S/N B020765 and Above 070-8003-02 Copyright © Tektronix, Inc. All rights reserved. Tektronix products are covered by U.S. and foreign patents, issued and pending. Information in this publication supercedes that in all previously published material. Specifications and price change privileges reserved. Printed in the U.S.A. Tektronix, Inc., P.O. Box 1000, Wilsonville, OR 97070–1000 TEKTRONIX and TEK are registered trademarks of Tektronix, Inc. WARRANTY Tektronix warrants that the products that it manufactures and sells will be free from defects in materials and workmanship for a period of one (1) year from the date of shipment. If a product proves defective during this warranty period, Tektronix, at its option, either will repair the defective product without charge for parts and labor, or will provide a replacement in exchange for the defective product. In order to obtain service under this warranty, Customer must notify Tektronix of the defect before the expiration of the warranty period and make suitable arrangements for the performance of service. Customer shall be responsible for packaging and shipping the defective product to the service center designated by Tektronix, with shipping charges prepaid. Tektronix shall pay for the return of the product to Customer if the shipment is to a location within the country in which the Tektronix service center is located. Customer shall be responsible for paying all shipping charges, duties, taxes, and any other charges for products returned to any other locations. This warranty shall not apply to any defect, failure or damage caused by improper use or improper or inadequate maintenance and care. -

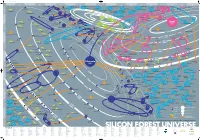

Silicon Forest Universe

15239 Poster 9/16/02 1:03 PM Page 1 AB CDE FGH I JKL M N O P Q R S Pearlsoft COMSAT General Integrated Systems Ashwood Group '85 Qualis Design fka CPU International Nel-Tech Development '98 Qsent '01 Briefsmart.com '00 Relyent TrueDisk Trivium Systems '80 '74 '99 '90 Gearbeat '81 Relational Systems Galois 3DLand Teradyne in 2001 '85 '00 '98 Solution Logic SwiftView Imagenation '89 Metro One IronSpire '84 Smart Mediary Systems Connections 13 Telecommunications WireX GenRad in 1996 '00 CyberOptics E-Core Salu Logiplex '79 MyHealthBank Semiconductor Cotelligent Technologies Fujitsu America Barco Metheus '77 '99 Group Knowledge fka United Data Biotronik Timlick & Associates in 1999 Gadget Labs Adaptive Solutions Wave International Processing Cascade Laser '98 Webridge Axis Clinical Software Mitron Basicon '91 GemStone fka Servio Logic Source Services '83 Integra Telecom Accredo FaxBack Polyserve Metheus Intersolv Babcock & Jenkins Electro '79 Informedics Scientific Sliceware Graphic Software Systems Industries IBM 12 in 1999 Atlas Telecom 1944 Sequent Computer ProSight Credence in 2001 19 ADC Kentrox '78 Oracle '69 Merant Datricon 60s Informix Systems FEI Sage Software fka Polytron MKTX 197 Mikros Nike 0s Etec Systems '63 19 Sentrol in 1995 Intel 80s SEH America Teseda Oregon Graduate Institute Flight Dynamics 1976 '97 1990 Purchasing Solutions Fluence ~ Relcom Vidco Mushroom Resources Cunningham & Cunningham '99 Myteam.com Praegitzer Industries Integrated Measurement Systems Zicon Digital World Lucy.Com Nonbox in 2001 ATEQ 11 Software Access