NORMAL STUDENTS EXCEPTIONAL DOUGHBOYS THESIS Presented

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

March 2014 Library Enews

March 2014 Vol. 2, No. 5 MESSAGE FROM Hey Undergrads! Don’t Let Citations Get Away From You OUR DIRECTOR Step Up Your Research Research Consultations, A Good Strategy Access Services Interlibrary Loan for Materials We Don’t Have Research Consultation Service— Learning Commons Beyond the Reference Desk New Collaboration Zone Offers Group Space THE REFERENCE DESK is a fixture in libraries where professional librarians and Collections Spotlight other library staff provide help in finding information. As the Internet and avail- Gartner Research Database: Emerging Technology ability of online resources has increased, library reference assistance has expanded to include Ask a Librarian services, adding online chat, e-mail, phone, and text options, Meet Our Staff as well as access to a librarian through online course sites like TRACS. Lisa Ancelet, Head Research, Instruction & Academic libraries also offer research consultation services, a one-to-one Outreach Librarian appointment with a librarian for extensive, in-depth research assistance. What can you expect from a research consultation? News from the North • Assistance in selecting the best resources for your research paper/project We’re Here for ALL Texas State Students • Help with developing research strategies • Strategies for searching specific databases Specialized Collections: Student Feature • Help searching the web for relevant and reliable information My True Loves—Music, Audiobooks, Movies • Explanations on how to gain access to material held in other libraries To have a productive consultation, you should have a research topic for which Special Events you need assistance. You will have the opportunity to discuss your topic in-depth Alkek Film Series Screens Two Free Films with a librarian, who will offer advice on what library resources will aid your research. -

Jerry Patterson, Commissioner Texas General Land Office General Land Office Texas STATE AGENCY PROPERTY RECOMMENDED TRANSACTIONS

STATE AGENCY PROPERTY RECOMMENDED TRANSACTIONS Report to the Governor October 2009 Jerry Patterson, Commissioner Texas General Land Office General Land Office Texas STATE AGENCY PROPERTY RECOMMENDED TRANSACTIONS REPORT TO THE GOVERNOR OCTOBER 2009 TEXAS GENERAL LAND OFFICE JERRY PATTERSON, COMMISSIONER INTRODUCTION SB 1262 Summary Texas Natural Resources Code, Chapter 31, Subchapter E, [Senate Bill 1262, 74th Texas Legislature, 1995] amended two years of previous law related to the reporting and disposition of state agency land. The amendments established a more streamlined process for disposing of unused or underused agency land by defining a reporting and review sequence between the Land Commissioner and the Governor. Under this process, the Asset Management Division of the General Land Office provides the Governor with a list of state agency properties that have been identified as unused or underused and a set of recommended real estate transactions. The Governor has 90 days to approve or disapprove the recommendations, after which time the Land Commissioner is authorized to conduct the approved transactions. The statute freezes the ability of land-owning state agencies to change the use or dispose of properties that have recommended transactions, from the time the list is provided to the Governor to a date two years after the recommendation is approved by the Governor. Agencies have the opportunity to submit to the Governor development plans for the future use of the property within 60 days of the listing date, for the purpose of providing information on which to base a decision regarding the recommendations. The General Land Office may deduct expenses from transaction proceeds. -

2017 Central Texas Runners Guide: Information About Races and Running Clubs in Central Texas Running Clubs Running Clubs Are a Great Way to Stay Motivated to Run

APRIL-JUNE EDITION 2017 Central Texas Runners Guide: Information About Races and Running Clubs in Central Texas Running Clubs Running clubs are a great way to stay motivated to run. Maybe you desire the kind of accountability and camaraderie that can only be found in a group setting, or you are looking for guidance on taking your running to the next level. Maybe you are new to Austin or the running scene in general and just don’t know where to start. Whatever your running goals may be, joining a local running club will help you get there faster and you’re sure to meet some new friends along the way. Visit the club’s website for membership, meeting and event details. Please note: some links may be case sensitive. Austin Beer Run Club Leander Spartans Youth Club Tejas Trails austinbeerrun.club leanderspartans.net tejastrails.com Austin FIT New Braunfels Running Club Texas Iron/Multisport Training austinfit.com uruntexas.com texasiron.net New Braunfels: (830) 626-8786 (512) 731-4766 Austin Front Runners http://goo.gl/vdT3q1 No Excuses Running Texas Thunder Youth Club noexcusesrunning.com texasthundertrackclub.com Austin Runners Club Leander/Cedar Park: (512) 970-6793 austinrunners.org Rogue Running roguerunning.com Trailhead Running Brunch Running Austin: (512) 373-8704 trailheadrunning.com brunchrunning.com/austin Cedar Park: (512) 777-4467 (512) 585-5034 Core Running Company Round Rock Stars Track Club Tri Zones Training corerunningcompany.com Youth track and field program trizones.com San Marcos: (512) 353-2673 goo.gl/dzxRQR Tough Cookies -

Hand to Hand Combat

*FM 21-150 i FM 21-150 ii FM 21-150 iii FM 21-150 Preface This field manual contains information and guidance pertaining to rifle-bayonet fighting and hand-to-hand combat. The hand-to-hand combat portion of this manual is divided into basic and advanced training. The techniques are applied as intuitive patterns of natural movement but are initially studied according to range. Therefore, the basic principles for fighting in each range are discussed. However, for ease of learning they are studied in reverse order as they would be encountered in a combat engagement. This manual serves as a guide for instructors, trainers, and soldiers in the art of instinctive rifle-bayonet fighting. The proponent for this publication is the United States Army Infantry School. Comments and recommendations must be submitted on DA Form 2028 (Recommended Changes to Publications and Blank Forms) directly to Commandant, United States Army Infantry School, ATTN: ATSH-RB, Fort Benning, GA, 31905-5430. Unless this publication states otherwise, masculine nouns and pronouns do not refer exclusively to men. iv CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION Hand-to-hand combat is an engagement between two or more persons in an empty-handed struggle or with handheld weapons such as knives, sticks, and rifles with bayonets. These fighting arts are essential military skills. Projectile weapons may be lost or broken, or they may fail to fire. When friendly and enemy forces become so intermingled that firearms and grenades are not practical, hand-to-hand combat skills become vital assets. 1-1. PURPOSE OF COMBATIVES TRAINING Today’s battlefield scenarios may require silent elimination of the enemy. -

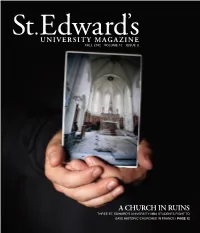

St. Edward's University Magazine Fall 2012 Issue

’’ StSt..EdwardEdwardUNIVERSITYUNIVERSITY MAGAZINEMAGAZINEss SUMMERFALL 20201121 VOLUME 112 ISSUEISSUE 23 A CHurcH IN RUINS THree ST. EDWarD’S UNIVERSITY MBA STUDENts FIGHT TO save HISTORIC CHurCHes IN FraNCE | PAGE 12 79951 St Eds.indd 1 9/13/12 12:02 PM 12 FOR WHOM 18 MESSAGE IN 20 SEE HOW THEY RUN THE BELLS TOLL A BOTTLE Fueled by individual hopes and dreams Some 1,700 historic French churches Four MBA students are helping a fourth- plus a sense of service, four alumni are in danger of being torn down. Three generation French winemaker bring her share why they set out on the rocky MBA students have joined the fight to family’s label to Texas. road of campaigning for political office. save them. L etter FROM THE EDitor The Catholic church I attend has been under construction for most of the The questions this debate stirs are many, and the passion it ignites summer. There’s going to be new tile, new pews, an elevator, a few new is fierce. And in the middle of it all are three St. Edward’s University MBA stained-glass windows and a bunch of other stuff that all costs a lot of students who spent a good part of the summer working on a business plan to money. This church is 30 years old, and it’s the third or fourth church the save these churches, among others. As they developed their plan, they had parish has had in its 200-year history. to think about all the people who would be impacted and take into account Contrast my present church with the Cathedral of the Assumption in culture, history, politics, emotions and the proverbial “right thing to do.” the tiny German village of Wolframs-Eschenbach. -

A Sharp Little Affair: the Archeology of Big Hole Battlefield

A Sharp Little Affair: The Archeology of the Big Hole Battlefield By Douglas D. Scott With Special Sections by Melissa A. Connor Dick Harmon Lester Ross REPRINTS IN ANTHROPOLOGY VOLUME 45 1994 Published by J & L Reprint Company 410 Wedgewood Drive Lincoln, Nebraska 68510 Revised for PDF publication June 2009 Acknowledgments First and foremost we wish to acknowledge and thank Hank Williams, Jr. for his interest and financial support. The National Park Service seldom has the luxury of conducting an archeological research project that is not tied to some development project or some overriding management action. Mr. William's support allowed us to pursue this investigation for the benefit of the park without being tied to a specific management requirement. His support did allow us to accomplish several management goals that otherwise would have waited their turn in the priority system. This project has had more than its fair share of those who have given their time, resources, and knowledge without thought of compensation. Specifically Irwin and Riva Lee are to be commended for their willingness to ramrod the metal detecting crew. They volunteered for the duration for which we are truly grateful. Aubrey Haines visited us during the field investigations and generously shared his vast knowledge of the Big Hole battle history with us. His willingness to loan material and respond to our questions is truly appreciated. Former Unit Manager Jock Whitworth and his entire staff provided much support and aid during the investigations. Jock and his staff allowed us to invade the park and their good-natured acceptance of our disruption to the daily schedule is acknowledged with gratitude. -

Groundwater Availability of the Barton Springs Segment of the Edwards Aquifer, Texas: Numerical Simulations Through 2050

GROUNDWATER AVAILABILITY OF THE BARTON SPRINGS SEGMENT OF THE EDWARDS AQUIFER, TEXAS: NUMERICAL SIMULATIONS THROUGH 2050 by Bridget R. Scanlon, Robert E. Mace*, Brian Smith**, Susan Hovorka, Alan R. Dutton, and Robert Reedy prepared for Lower Colorado River Authority under contract number UTA99-0 Bureau of Economic Geology Scott W. Tinker, Director The University of Texas at Austin *Texas Water Development Board, Austin **Barton Springs Edwards Aquifer Conservation District, Austin October 2001 GROUNDWATER AVAILABILITY OF THE BARTON SPRINGS SEGMENT OF THE EDWARDS AQUIFER, TEXAS: NUMERICAL SIMULATIONS THROUGH 2050 by Bridget R. Scanlon, Robert E. Mace*1, Brian Smith**, Susan Hovorka, Alan R. Dutton, and Robert Reedy prepared for Lower Colorado River Authority under contract number UTA99-0 Bureau of Economic Geology Scott W. Tinker, Director The University of Texas at Austin *Texas Water Development Board, Austin **Barton Springs Edwards Aquifer Conservation District, Austin October 2001 1 This study was initiated while Dr. Mace was an employee at the Bureau of Economic Geology and his involvement primarily included initial model development and calibration. CONTENTS ABSTRACT .......................................................................................................................................1 INTRODUCTION..............................................................................................................................1 STUDY AREA...................................................................................................................................3 -

The Royal Engineers Journal

THE ROYAL ENGINEERS JOURNAL. Vol. III. No. 2. FEBRUARY, 1906. CONTENTS. 1. Royal Engineer Duties n the Future. PAGo. By Bt. Col. E. R. KENYON, R.E. 2. Organisatton of oyal Engineer 81 Capt. Units for Employment with C. DE W. CROOKSHANK, R.E. Cavalry. By (With Photo) ... 3. Entrenching under Fire. 84 By Bt. Lt.-Col. G. M. HEATH, D.s.o., Photos) ... ... ... ... R.E. (With 4. Some Notes on the Modern Coast Fortress. 91 By Col. T. RYDER MAIN, C.B., The MechanalC Conveyance R.E. 93 of Order. By Major L.J. DOPPING-HEPENsTAL 6 The Engineers of the German R E. Army. By Col. J. A. FERRIER, D.S.., R.E... 7. Transcripts:-Hutted 105 Hospitals in War. (With Plate) Some Work by the Electrical 124 Engineers, R.E. (V.) .. 8. Review:--The Battle ... 138 oe Wavre and Grouchy' Re treat. (Col. By W. Hyde Kelly, R.E. E. M. Lloyd, late R.E.) 9. Notices of Magazines .. 141 10. Correspondence:-The '43 Prevention of Dampness due to Condensation By Major in Magazines. T. E. NAIS, R.E. ... 11. Reeent PnbRcllinan ... 155 ....JV"O ... ... .. ... ... '57 INSTITUTION OF RE OFFICE COPY PRICE, DO NOT REMOVE SOME PUBLICATIONS BY THE ROYAL ENGINEERS INSTITUTE. NET PBICE TO NON- TITLE AND AUTHOR. MEMBERS. s. d. 1902 5 0 Edition ........... 3x.............. 5" B.E. Field Service pocket-Book. 2nd an Account of the Drainage and The Destruction of Mosquitos, being this object during 1902 and 1903 at other works carried out with 2 6 Hodder, R.E ...... ...............1904 St. Lucia, West Indies, by Major W. -

1892-1929 General

HEADING RELATED YEAR EVENT VOL PAGE ABOUKIR BAY Details of HM connections 1928/112 112 ABOUKIR BAY Action of 12th March Vol 1/112 112 ABUKLEA AND ABUKRU RM with Guards Camel Regiment Vol 1/73 73 ACCIDENTS Marine killed by falling on bayonet, Chatham, 1860 1911/141 141 RMB1 marker killed by Volunteer on Plumstead ACCIDENTS Common, 1861 191286, 107 85, 107 ACCIDENTS Flying, Captain RISK, RMLI 1913/91 91 ACCIDENTS Stokes Mortar Bomb Explosion, Deal, 1918 1918/98 98 ACRE, SORTIE FROM (1799) Death of Major Oldfield Vol 1/111 111 ACRE, SORTIE FROM (1799) Turkish Medal awarded to C/Sgt W Healey 1901/122 122 ACRE, SORTIE FROM (1799) Ball at Plymouth in 1804 to commemorate 1905/126 126 ACRE, SORTIE FROM (1799) Death of a Veteran 1907/83 83 ACRE, SORTIE FROM (1799) Correspondence 1928/119 119 ACRE, SORTIE FROM (1799) Correspondence 1929/177 177 ACRE, SORTIE FROM (1799) 1930/336 336 ACRE, SORTIE FROM (1799) Syllabus for Examination, RMLI, 1893 Vol 1/193 193 ACRE, SORTIE FROM (1799) of Auxiliary forces to be Captains with more than 3 years Vol 3/73 73 ACTON, MIDDLESEX Ex RM as Mayor, 1923 1923/178 178 ADEN HMS Effingham in 1927 1928/32 32 See also COMMANDANT GENERAL AND GENERAL ADJUTANT GENERAL OFFICER COMMANDING of the Channel Fleet, 1800 1905/87 87 ADJUTANT GENERAL Change of title from DAGRM to ACRM, 1914 1914/33 33 ADJUTANT GENERAL Appointment of Brigadier General Mercer, 1916 1916/77 77 ADJUTANTS "An Unbroken Line" - eight RMA Adjutants, 1914 1914/60, 61 60, 61 ADMIRAL'S REGIMENT First Colonels - Correspondence from Lt. -

Albert B. Alkek Library 1

Albert B. Alkek Library 1 ALBERT B. ALKEK LIBRARY Alkek Library www.library.txstate.edu (http://www.library.txstate.edu) T: 512.245.2686 F: 512.245.0392 The Alkek Library contains more than 1.5 million print materials, including books, documents, theses/dissertations, and other resources. The library provides access to 600,000 ebooks, 500+ databases, more than 180,000 audiovisual materials, and more than 700,000 microform materials. Special holdings of the Library include the Wittliff Collections (comprised of the Southwestern Writers Collection and the Southwestern and Mexican Photography Collection,) and the University Archives. The Library is also a selective depository for federal government documents. As a member of the Texas Digital Library, the Library’s Digital Collections (http://digital.library.txstate.edu/ ) provides access to unique Texas State collections, including scholarship authored by university faculty, students, and staff and selected materials from The Wittliff Collections and the University Archives. The Library's online catalog (http://catalog.library.txstate.edu ) provides information on the Library’s holdings. Wireless access to the university network is available within the Library. Laptop computers may be checked-out for building use. The Learning Commons provides workstations, laser printers, scanners, video conferencing and video- editing equipment, presentation and GIS technology support, an Open Theater workshop space and adaptive equipment for individuals with disabilities. The Library maintains cooperative borrowing agreements with other libraries in the region. Through TexShare, a statewide resource sharing program, students and faculty may borrow materials held by most public and private university libraries in the state. Materials may be transferred, by request, to the Texas State University Library in Round Rock.. -

Quiet Study Floor

Call Number Map 5th Floor Group Study Restrooms Quiet Study Floor A B D G → GV HD HN Oversize A - HN HX J J D E F GV→HD Group Study Elevators University Archives th 6 Floor Group Study Restrooms Quiet Study Floor K L ML PR PS Q QH Oversize K - T ML N P PR→PS QH R Group Study Elevators R → S → T th Group Study 7 Floor Restrooms Z - Z ← V ← U ← T T Oversize The Wittliff Collections Group Study Elevators Directory Albert B. Alkek Library Texas State University http://www.library.txstate.edu First Floor (basement level): Room 100 Instructional Technology offices and classrooms ……………….…………………………..…….………..245-2319 Student lounge and open computers, Library rooms 101/105/106 Second Floor (main entrance): Circulation / Reserve Desk …..………………………………….……………….....……………………..………….……………….245-3681 Fax machine, Interlibrary Loan pick up, Color printing pick up, Lost & Found, Security Guard Research & Information Desk …..………………………………….………………...…………………………….……..………… 245-2686 Computers, Printers, Café, Open Theater, Collaboration Rooms Associate Vice‐President, University Library, Room 204 ....……………………...…………….....…………........... 245-2133 Third Floor: Periodicals / Media Desk………………………....……………………….…………………….…….................................... 245-3894 Current and bound periodicals (1960‐current), Popular Reading Collection, Microfilm/microfiche, DVDs, CDs, Language Learning CDs, Models, Kits, Graphic Novels, Secured Collection, Juvenile Collection, TCMC Collection (K‐12 Textbooks, Scholastic Guided Reading), Testing Collection, Reference Collection, Career -

NPRC) VIP List, 2009

Description of document: National Archives National Personnel Records Center (NPRC) VIP list, 2009 Requested date: December 2007 Released date: March 2008 Posted date: 04-January-2010 Source of document: National Personnel Records Center Military Personnel Records 9700 Page Avenue St. Louis, MO 63132-5100 Note: NPRC staff has compiled a list of prominent persons whose military records files they hold. They call this their VIP Listing. You can ask for a copy of any of these files simply by submitting a Freedom of Information Act request to the address above. The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website.