6 Osteoporosis and Fractures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pneumorrhachis of Thoracic Spine After Gunshot Wound Farooq Azam Rathore1, Zaheer Ahmad Gill2 and Malik Muhammad Amjad Yasin3

CASE REPORT Pneumorrhachis of Thoracic Spine After Gunshot Wound Farooq Azam Rathore1, Zaheer Ahmad Gill2 and Malik Muhammad Amjad Yasin3 ABSTRACT Air in the spinal canal (Pneumorrhachis) is a rare complication of traumatic spinal injuries reported at various levels of the spinal canal. Pneumorrhachis resolves spontaneously most of the times. Rarely, it may cause cord compression. It is important to rule out potentially serious causes like basilar skull fracture, injury to lungs, mediastinum, mastoid air cells, frontal sinuses or intestine. We present a case of pneumorrhachis in a young soldier who sustained gunshot wound in neck, resulting in spinal cord injury, He was managed conservatively and pneumorrhachis resolved spontaneously without complications. Pathogenesis along with review of relevant literature is presented. Key words: Pneumorrhachis. Air. Spinal canal. Spinal cord injury. Gunshot wound. Pakistan. INTRODUCTION evacuated to a tertiary care hospital by road. Upon Air in the spinal canal is called pneumorrhachis. It is also arrival, he had stable vital signs with a Glasgow Coma described as aerorachia, intraspinal pneumocele, Scale score of 15 and could recount the events leading pneumosaccus or pneumomyelogram.1 It is a rare but to his injury. There were no complaints of dysphagia or documented complication of many traumatic (pneumo- respiratory difficulty at presentation and during his stay thorax, spinal fracture, basilar skull fracture) and non- at the rehabilitation department. traumatic events (vertebral metastases, spontaneous X-rays of the thoracic spine revealed comminuted pneumomediastinum).2-6 fracture of the first dorsal vertebra (DV1), while X-ray Presence of air in spinal canal itself is harmless and chest was negative for pneumothorax or mediastinal absorbs spontaneously in due course of time, yet some widening (Figure 1). -

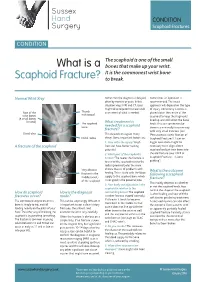

What Is a Scaphoid Fracture?

Sussex Hand CONDITION Surgery Scaphoid Fractures CONDITION The scaphoid is one of the small What is a bones that make up your wrist. It is the commonest wrist bone Scaphoid Fracture? to break. Normal Wrist Xray Sometimes the diagnosis is delayed, Sometimes an operation is often by months or years. In this recommended. The exact situation xrays, MRI and CT scans approach will depend on the type might all be required to make a full of injury. Commonly a screw is Rest of the Thumb assessment of what is needed. placed down the centre of the metacarpal wrist bones scaphoid to keep the fragments (8 small bones lined up and still whilst the bone in total) The scaphoid What treatment is heals. This can sometimes be bone needed for a scaphoid done in a minimally invasive way fracture? with very small incisions (see Distal ulna This depends on a great many ‘Percutaneous screw fixation of Distal radius things. Some important factors are: Scaphoid Fractures’). Later on 1. How old is the injury? Fresh bigger operations might be A fracture of the scaphoid fractures have better healing necessary to re-align a bent potential scaphoid and put new bone into 2. Which part of the scaphoid is the old fracture (see ‘ORIF of broken? The nearer the fracture is Scaphoid Fractures +/-bone to end of the scaphoid next to the grafting’). radius (proximal pole) the more Very obvious chance there is of problems with What is the outcome fracture in the healing. This is to do with the blood following a scaphoid middle (waist) supply to the scaphoid bone which fracture? of the scaphoid is not good in the proximal pole. -

Neurologic Deterioration Secondary to Unrecognized Spinal Instability Following Trauma–A Multicenter Study

SPINE Volume 31, Number 4, pp 451–458 ©2006, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Inc. Neurologic Deterioration Secondary to Unrecognized Spinal Instability Following Trauma–A Multicenter Study Allan D. Levi, MD, PhD,* R. John Hurlbert, MD, PhD,† Paul Anderson, MD,‡ Michael Fehlings, MD, PhD,§ Raj Rampersaud, MD,§ Eric M. Massicotte, MD,§ John C. France, MD, Jean Charles Le Huec, MD, PhD,¶ Rune Hedlund, MD,** and Paul Arnold, MD†† Study Design. A retrospective study was undertaken their neurologic injury. The most common reason for the that evaluated the medical records and imaging studies of missed injury was insufficient imaging studies (58.3%), a subset of patients with spinal injury from large level I while only 33.3% were a result of misread radiographs or trauma centers. 8.3% poor quality radiographs. The incidence of missed Objective. To characterize patients with spinal injuries injuries resulting in neurologic injury in patients with who had neurologic deterioration due to unrecognized spine fractures or strains was 0.21%, and the incidence as instability. a percentage of all trauma patients evaluated was 0.025%. Summary of Background Data. Controversy exists re- Conclusions. This multicenter study establishes that garding the most appropriate imaging studies required to missed spinal injuries resulting in a neurologic deficit “clear” the spine in patients suspected of having a spinal continue to occur in major trauma centers despite the column injury. Although most bony and/or ligamentous presence of experienced personnel and sophisticated im- spine injuries are detected early, an occasional patient aging techniques. Older age, high impact accidents, and has an occult injury, which is not detected, and a poten- patients with insufficient imaging are at highest risk. -

EM Cases Digest Vol. 1 MSK & Trauma

THE MAGAZINE SERIES FOR ENHANCED EM LEARNING Vol. 1: MSK & Trauma Copyright © 2015 by Medicine Cases Emergency Medicine Cases by Medicine Cases is copyrighted as “All Rights Reserved”. This eBook is Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 3.0 Unsupported License. Upon written request, however, we may be able to share our content with you for free in exchange for analytic data. For permission requests, write to the publisher, addressed “Attention: Permissions Coordinator,” at the address below. Medicine Cases 216 Balmoral Ave Toronto, ON, M4V 1J9 www.emergencymedicinecases.com This book has been authored with care to reflect generally accepted practices. As medicine is a rapidly changing field, new diagnostic and treatment modalities are likely to arise. It is the responsibility of the treating physician, relying on his/her experience and the knowledge of the patient, to determine the best management plan for each patient. The author(s) and publisher of this book are not responsible for errors or omissions or for any consequences from the application of the information in this book and disclaim any liability in connection with the use of this information. This book makes no guarantee with respect to the completeness or accuracy of the contents within. OUR THANKS TO... EDITORS IN CHIEF Anton Helman Taryn Lloyd PRODUCTION EDITOR Michelle Yee PRODUCTION MANAGER Garron Helman CHAPTER EDITORS Niran Argintaru Michael Misch PODCAST SUMMARY EDITORS Lucas Chartier Keerat Grewal Claire Heslop Michael Kilian PODCAST GUEST EXPERTS Andrew Arcand Natalie Mamen Brian Steinhart Mike Brzozowski Hossein Mehdian Arun Sayal Ivy Cheng Sanjay Mehta Laura Tate Walter Himmel Jonathan Pirie Rahim Valani Dave MacKinnon Jennifer Riley University of Toronto, Faculty of Medicine EM Cases is a venture of the Schwartz/ Reisman Emergency Medicine Institute. -

Osteoporosis and Vertebral Compression (Spinal) Fractures Fact Sheet

Osteoporosis and Vertebral Compression (Spinal) Fractures Fact Sheet About Osteoporosis • Osteoporosis is estimated to affect 200 million women worldwide.1 • Worldwide, osteoporosis causes more than nine million fractures annually, resulting in an osteoporotic fracture every three seconds.1 • A recent report issued by the Surgeon General noted that by 2020, one in two Americans over age 50 will be at risk for fractures from osteoporosis and low bone mass.2 • Although prevalent, 75 percent of women and 90 percent of men with a high likelihood of developing osteoporosis are not investigated. 3 • Up to 80 percent who have already had at least one osteoporotic fracture are neither identified nor treated.3 • Overall, 61 percent of osteoporotic fractures occur in women, with a female-to-male ratio of 1.6.4 • A prior fracture is associated with an 86 percent increased risk of any fracture.5 • In 2005, osteoporosis-related fractures cost the U.S. health care system about $17 billion per year.6 • Osteoporosis takes a huge personal and economic toll. In Europe, the disability due to osteoporosis is greater than that caused by cancers (with the exception of lung cancer) and is comparable to or greater than that lost to a variety of chronic non- communicable diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and ischemic heart disease.4 PMD009493-1.0 About Vertebral Compression (Spinal) Fractures • Osteoporosis causes more than 700,000 spinal fractures each year in the U.S. – more than twice the annual number of hip fractures1 – accounting for more than 100,000 hospital admissions and resulting in close to $1.5 billion in annual costs.8 • Vertebral fractures are the most common osteoporotic fracture, yet approximately two-thirds are undiagnosed and untreated. -

Long-Term Posttraumatic Survival of Spinal Fracture Patients in Northern Finland

SPINE Volume 43, Number 23, pp 1657–1663 ß 2018 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved. EPIDEMIOLOGY Long-term Posttraumatic Survival of Spinal Fracture Patients in Northern Finland Ville Niemi-Nikkola, BM,Ã,y Nelli Saijets, BM,Ã,y Henriikka Ylipoussu, BM,Ã,y Pietari Kinnunen, MD, PhD,z Juha Pesa¨la¨,MD,z Pirkka Ma¨kela¨,MD,z Markku Alen, MD, PhD,Ã,§ Mauri Kallinen, MD, PhD,Ã,§ and Aki Vainionpa¨a¨, MD, PhDÃ,§,{ age groups of 50 to 64 years and over 65 years, the most Study Design. A retrospective epidemiological study. important risk factors for death were males with hazard ratios of Objective. To reveal the long-term survival and causes of death 3.0 and 1.6, respectively, and low fall as trauma mechanism after traumatic spinal fracture (TSF) and to determine the with hazard ratios of 9.4 and 10.2, respectively. possible factors predicting death. Conclusion. Traumatic spinal fractures are associated with Summary of Background Data. Increased mortality follow- increased mortality compared with the general population, high ing osteoporotic spinal fracture has been represented in several mortality focusing especially on older people and men. The studies. Earlier studies concerning mortality after TSF have increase seems to be comparable to the increase following hip focused on specific types of fractures, or else only the mortality fracture. Patients who sustain spinal fracture due to falling need of the acute phases has been documented. In-hospital mortality special attention in care, due to the observation that low fall as has varied between 0.1% and 4.1%. -

Scaphoid Fracture PA Radiograph

30 y/o male with acute left wrist pain Student Name….None was listed Atul Kumar, MD, MS PA Radiograph Non Contrast Coronal CT ? Scaphoid Fracture PA radiograph Distal pole Scaphoid fracture Proximal pole • PA x-ray showing transverse scaphoid fracture. Non Contrast Coronal CT Capitate Trapezoid Hamate Trapezium Triquetrum Lunate Scaphoid fracture Scaphoid Fracture • Mechanism: direct axial compression or with hyperextension (fall onto an outstretched hand). • Symptoms: pain localized at the radial aspect of wrist often associated with swelling and reduced grip strength. – Pain in anatomic snuffbox suspicious for waist fracture, which is the most common type. • Because scaphoid fractures are often radiologically occult, any tenderness in the anatomic snuffbox should be treated as a scaphoid fracture. • Scaphoid blood supply (palmar carpal branch of the radial artery) runs from the distal to the proximal pole. Transverse fracture of the proximal pole can lead to osteonecrosis and nonunion due to disruption of blood flow. http://epmonthly.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/OrthoB.png Scaphoid Fracture • Differential diagnosis: distal radius fracture, wrist sprain, and other carpal injuries other than scaphoid. • In suspected scaphoid fractures, plain radiographs (including PA, true lateral, oblique, and scaphoid views) are ordered as the first diagnostic step. • However, the false negative rate for radiographs taken immediately after injury up to 20-54%. • Definitive diagnosis can be made by MRI or CT scan. They have a comparable diagnostic accuracy and do not result in overtreatments. Avascular necrosis/Nonunion Scaphoid view radiograph (A) and CT scan (B) showing nonunion (arrow) and avascular necrosis (asterisk) and the Terry Thomas sign – scapholunate ligament injury (arrowhead). -

Spinal Fractures.Pdf

Spinal Fractures Overview Spinal fractures are different than a broken arm or leg. A fracture or dislocation of a vertebra can cause bone fragments to pinch and damage the spinal nerves or spinal cord. Most spinal fractures occur from car accidents, falls, gunshot, or sports. Injuries can range from relatively mild ligament and muscle strains, to fractures and dislocations of the bony vertebrae, to debilitating spinal cord damage. Depending on how severe your injury is, you may experience pain, difficulty walking, or be unable to move your arms or legs (paralysis). Many fractures heal with conservative treatment; however severe fractures may require surgery to realign the bones. Spinal column and spinal cord To understand spinal fractures, it is helpful to understand how your spine works (see Anatomy of the Spine). Your spine is made of 33 bones called vertebrae that provide the main support for your body, allowing you to stand upright, bend, and Figure 1. Vertebrae have 3 main parts. The body is a twist. In the middle of each vertebra is a hollow weight-bearing surface and an attachment for the disc. The vertebral arch forms the spinal canal through which space called the spinal canal, which provides a the spinal cord runs. The processes arise from the protective space for the spinal cord (Fig. 1). The vertebral arch to form the facet joints and processes for spinal cord serves as an information super-highway, muscle attachment. relaying messages between the brain and the body. Spinal nerves branch off the spinal cord, pass between the vertebrae, to innervate all parts of your body. -

Wrist Injury Article 12-19-16

ARTICLE: Wrist Injuries This week we are going to talk about 3 unusual wrist injuries all of which can cause considerable problems and the potential complications of each. The first is a TFCC injury. The TFCC or triangular fibrocartilage is a small meniscus or pad on the ulnar side of the wrist (pinky side) which can become torn during a fall on an outstretched hand and can cause clicking, popping and pain on this side of the wrist. The TFCC is sometimes difficult to detect and often misdiagnosed as a wrist sprain but is rather different than a sprained wrist in that it is not an injury of ligament but is an injury of cartilage. The injury can be spotted with a shear test and is properly diagnosed with an arthrogram. The second unusual injury to the wrist is the scaphoid fracture. The scaphoid fracture of the wrist is a bone injury which occurs when the scaphoid bone on the radial side of the wrist (thumb side) is broken at it’s waist (center) injuring the blood supply to the proximal pole of the scaphoid. This injury results in avascular necrosis or bone death of the scaphoid. Also occurring after a fall on an outstretched hand the scaphoid fracture is often misdiagnosed as a wrist sprain but is more correctly described as a fracture. The hallmark symptom of a scaphoid fracture is it’s failure to heal and persistent pain on the radial side of the wrist. The scaphoid fracture is often missed on the initial x-ray as the bone has not had time yet to die off and is often seen on a second film. -

Your Wrist Bones

www.healthinfo.org.nz Your wrist bones Your wrist is made up of eight small bones (called the carpal bones). Each carpal bone has a specific name, shown in the image on the right. The carpal bones connect with the two long bones in your forearm (the radius and ulna). Your wrist moves where they connect. This makes your wrist a very complex structure, as there are many different joints within it. If any one of your carpal bones breaks, it can change position slightly, causing pain and problems with movement. Occasionally it can also lead to arthritis. Causes of a broken wrist A broken wrist usually happens from falling on to an outstretched hand. Serious accidents, such as car accidents, motorcycle accidents, or falls from a ladder cause more serious breaks. Weak bones (for example, in someone with osteoporosis) tend to break more easily. If you break your wrist without significant force, your doctor may recommend checking if you have osteoporosis. If you meet the criteria, they may send you for a bone density scan. Any one of the 10 bones in your wrist can break, but the most common bone to break is the radius, in your forearm. This is called a distal radius fracture. Another common wrist fracture is a scaphoid fracture, which is a break in one of your small carpal bones. This can be difficult to diagnose, and there is a risk a scaphoid fracture might not heal. Your wrist can break in many different ways, and some breaks are worse than others. How bad a break it is depends on how many pieces a bone breaks into, whether they are stable or move around a lot, and whether the broken ends of the bone are still in the right place. -

Fractures of the Thoracic and Lumbar Spine - Orthoinfo - AAOS 15/09/12 9:10 AM

Fractures of the Thoracic and Lumbar Spine - OrthoInfo - AAOS 15/09/12 9:10 AM Copyright 2010 American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons Fractures of the Thoracic and Lumbar Spine A spinal fracture is a serious injury. The most common fractures of the spine occur in the thoracic (midback) and lumbar spine (lower back) or at the connection of the two (thoracolumbar junction). These fractures are typically caused by high-velocity accidents, such as a car crash or fall from height. Men experience fractures of the thoracic or lumbar spine four times more often than women. Seniors are also at risk for these fractures, due to weakened bone from osteoporosis. Because of the energy required to cause these spinal fractures, patients often have additional injuries that require treatment. The spinal cord may be injured, depending on the severity of the spinal fracture. Understanding how your spine works will help you to understand spinal fractures. Learn more about your spine: Spine Basics (topic.cfm?topic=A00575) Cause Fractures of the thoracic and lumbar spine are usually caused by high-energy trauma, such as: Car crash Fall from height Sports accident Violent act, such as a gunshot wound Spinal fractures are not always caused by trauma. For example, people with osteoporosis, tumors, or other underlying conditions that weaken bone can fracture a vertebra during normal, daily activities. Types of Spinal Fractures There are different types of spinal fractures. Doctors classify fractures of the thoracic and lumbar spine based upon pattern of injury and whether there is a spinal cord injury. Classifying the fracture patterns can help to determine the proper treatment. -

ICD-10-CM TRAINING November 26, 2013

ICD-10-CM TRAINING November 26, 2013 Injuries, Poisonings, and Certain Consequences of External Causes of Morbidity Linda Dawson, RHIT AHIMA ICD-10-CM/PCS Trainer Seventh Character The biggest change in injury/poisoning coding: The 7th character requirement for each applicable code. Most categories have three 7th character values A – Initial encounter –Patient receiving active treatment for the condition. Surgical treatment, ER, evaluation and treatment by a new physician (Consultant) D- Subsequent encounter - Encounters after the patient has received active treatment. Routine care during the healing or recovery phase. Cast change or removal. Removal of internal or external fixator, medication adjustment, other aftercare follow-up visits following treatment of the injury or condition. S- Sequela - Complications of conditions that arise as a direct result of a conditions, such as scar formations after a burn. The scars are a sequelae of the burn. Initial encounter Patient seen in the Emergency room for initial visit of sprain deltoid ligament R. ankle S93.421A Patient seen by an orthopedic physician in consultation, 2 days after the initial injury for evaluation and care of sprain S93.421A Subsequent encounters : Do not use aftercare codes Injuries or poisonings where 7th characters are provided to identify subsequent care. Subsequent care of injury – Code the acute injury code 7th character “D” for subsequent encounter T23.161D Burn of back of R. hand First degree- visit for dressing change Seventh Character When using the 7th character of “S” use the injury code that precipitated the injury and code for the sequelae. The “S” is added only to the injury code.