Deep Brain Stimulation of the Subthalamic Nucleus in Obsessive

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NEWS RELEASE Grenoble, June 10, 2015

NEWS RELEASE Grenoble, June 10, 2015 Clinatec Chairman Alim-Louis Benabid Honored by International Neuromodulation Society ‘Giant of Neuromodulation Award’ Recognizes Benabid’s Pioneering Work In Treating Symptoms of Parkinson’s Disease, Essential Tremor and Dystonia The International Neuromodulation Society (INS) today presented its third annual “Giant of Neuromodulation Award” to Prof. Alim-Louis Benabid, board chairman of Clinatec – The Edmond J. Safra Biomedical Research Center in Grenoble, France. Meeting at its 12th World Congress in Montreal, the society recognized Benabid for clinical work in the 1980s that helped usher in the modern era of using deep brain stimulation (DBS) to manage motor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease, essential tremor and dystonia. Benabid, who co-founded Clinatec in 2006, is the first award recipient who is renowned for work in neuromodulation for movement disorder. Clinatec – The Edmond J. Safra Biomedical Research Center conducts research on the frontier of health care and micro- and nanoelectronics. Its teams of medical doctors, biologists, mathematicians, engineers and other specialists bring a unique, multidisciplinary approach to diagnosis and treatment of neurodegenerative diseases, cancer and motor disabilities, and development of innovative biomedical devices to improve patient lives. “Prof. Benabid’s pioneering role in developing deep brain stimulation for treating Parkinson’s disease and other neurological disorders demonstrates the potential benefits that can be achieved by applying advanced technologies to medicine,” said Marie-Noëlle Semeria, CEO of CEA-Leti, the French microelectronics research institute that helped launch Clinatec. “This vision drives the research at Clinatec, where clinicians work hand in hand with experts in advanced technologies to discover new treatments for some of humanity’s most serious diseases.” The Giant of Neuromodulation Award has been presented at biennial congresses of the nonprofit International Neuromodulation Society since 2011, reflecting the growth and maturity of the field. -

Grenoble Alpes University Hospital

GRENOBLE ALPES UNIVERSITY HOSPITAL Grenoble Alpes University Hospital CHUGA (CHU Grenoble Alpes) Grenoble Alpes University Hospital is the reference hospital in the alpine region. Population of the region : 2 million people Grenoble is located: • 1h from Lyon • 1h30 from Geneva • 3h from Paris • 4h from Milano 2 At the heart of a unique health ecosystem in France Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Grenoble Alpes Grenoble: a unique health ecosystem in the heart of the Alps 4 Grenoble: a unique health ecosystem in the heart of the Alps 5th most inventive city in the World (Forbes, July 2013) Strongest focus on research in France A UNIQUE ENVIRONMENT IN MEDICAL TECHNOLOGIES Computer- Clusters for assisted medical medical research interventions and innovation Medical software Silver economy expertise World firsts « made in Grenoble » : First neurosurgery robot First navigation of total knee surgery 5 A Hospital in partnership with a world-class University 2019 Shanghai ranking : French top 7 / World top 200 2019 Reuters’ ranking - Europe most innovative universities : # 33 • In 2016, Grenoble Alpes University was granted the IDEX Label - Excellence Initiatives – by an international jury. This label, granted to only 10 French Universities, aims to create world-class teaching and research centers of excellence. 2019: Grenoble in French top 5 of « Best city to study » • Medical and pharmacy schools : at the edge of innovation in education A culture of innovation in education : Problem-based education, tutoring, flipped education, digital -

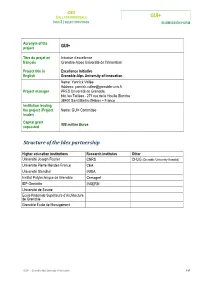

GUI+ Structure of the Idex Partnership

IDEX CALL FOR PROPOSALS GUI+ IDEX 2 | SELECTION PHASE SUBMISSION FORM Acronym of the project GUI+ Titre du projet en Initiative d’excellence français Grenoble-Alpes Université de l’Innovation Project title in Excellence Initiative English Grenoble-Alps University of Innovation Name: Yannick Vallée Address: [email protected] Project manager PRES Université de Grenoble bât. les Taillées - 271 rue de la Houille Blanche 38400 Saint Martin d'Hères – France Institution leading the project (Project Name: GUI+ Committee leader) Capital grant 908 million Euros requested Structure of the Idex partnership Higher education institutions Research institutes Other Université Joseph Fourier CNRS CHUG (Grenoble University Hospital) Université Pierre Mendes-France CEA Université Stendhal INRIA Institut Polytechnique de Grenoble Cemagref IEP Grenoble INSERM Université de Savoie Ecole Nationale Supérieure d’Architecture de Grenoble Grenoble École de Management GUI+ | Grenoble-Alps University of Innovation 1/87 IDEX CALL FOR PROPOSALS GUI+ IDEX 2 | SELECTION PHASE SUBMISSION FORM 1 CONTENTS 2 ADDITIONAL FILE: OPERATIONAL MEASURES ............................................................................ 3 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................... 12 4 DELTA DOCUMENT ................................................................................................................ 18 4.1 The legal status of the structure carrying the Idex ..................................................................18 -

REPORT2019-LETI-Web

TECHNOLOGY RESEARCH INSTITUTE 2019 SCIENTIFIC REPORT 2019 SCIENTIFIC REPORT TECHNOLOGY RESEARCH INSTITUTE LETI 2019 Scientific Report LETI 2019 Scientific Report “CREATIVITY Emmanuel IS INTELLIGENCE Sabonnadière HAVING FUN.” Chief Executive Officer Albert Einstein As one of France’s leading research institutes in the fields of micro and nanoelectronics, CEA-Leti actively supports society’s digital transition—in energy, the environment, and the future of medicine—driven Thomas Ernst by the French Alternative Energies and Atomic Energy VP for Science © Benjamin Zwarts © CEA-Leti Commission (CEA). and Technology he digital transition, which aligns closely with CEA-Leti’s Our last two programs are integrated LiDAR and 5G. They are With the digital revolution well underway, the core expertise, underpins advances in all of these fields, rooted in the cyber-physical systems domain, an area in which use of information technology is expanding faster Tand the institute is running a far-reaching program on we have a long history of early-stage research with our industrial than ever before in fields like transportation, embedded artificial intelligence that will accelerate/boost partners. These technologies are mature, and our R&D is tailored the digital transition. This program is foundational in that it to specific market applications. Here, we leverage the power of telecommunications, healthcare, and augmented will bring the groundbreaking semiconductor technologies our cleanrooms outfitted with the most advanced More-than- reality. The challenge now is to achieve much finer we have developed with our partners over the past several Moore production equipment and the passion for innovation integration. This means inventing new system and years to the forefront. -

IDEX Grenoble

APPEL A PROJETS IDEX GUI+ 2010 DOCUMENT B Phase de présélection Acronyme du projet GUI+ d’Idex Titre du projet en Initiative d’excellence français Grenoble Alpes Université de l’Innovation Excellence Initiative Project title in English Grenoble Alps University of Innovation Nom : Yannick Vallée Personne en charge de Coordonnées : [email protected] la coordination du PRES Université de Grenoble – projet bât. les Taillées - 271 rue de la Houille Blanche - 38400 Saint Martin d'Hères - France Institution portant le Nom : Comité GUI+ projet (le porteur) Dotation en capital 1,2 milliard d’euros demandée (a) Composition du groupement constituant l’Idex Etablissements Organismes de recherche Autres d’enseignement supérieur et de recherche Université Joseph Fourier CNRS CHU de Grenoble Université Pierre Mendes-France CEA Université Stendhal INRIA Institut Polytechnique de Grenoble Cemagref IEP Grenoble INSERM Université de Savoie Ecole Nationale Supérieure d’Architecture de Grenoble Grenoble École de Management 1/59 APPEL A PROJETS IDEX GUI+ 2010 DOCUMENT B Sommaire 1. AMBITION ET STRATEGIE DU PROJET ................................................................................... 3 2. STRUCTURE ET CARACTERISATION DE L’INITIATIVE D’EXCELLENCE ............................................... 6 2.1. Présentation du porteur du projet ........................................................................................... 6 2.2. Candidature aux actions du Programme « Investissements d’avenir » .............................................. 6 2.3. Périmètre d’excellence, environnement, perspectives et valeur ajoutée ............................................ 8 2.3.1 L’excellence en recherche : au service de la société 8 2.3.2 L’excellence en formation : des actions de formation en relation avec le périmètre d’excellence recherche 10 2.3.3 La valorisation 13 2.3.4 Partenaires 14 2.3.5 Positionnement européen et international 14 3. -

Leti Sensors Used in Future Bio-Artificial Liver

NEWSLETTER Top news Innovation Smart car windshields Leti sensors in full color EA-Leti researchers are working with Optys (a Nexter company) to improve smart car C windshield technology and get it ready for manufacturing. used in Smart windshields display information useful to drivers for an augmented-reality experience at the wheel. The helmet-based system in development includes both data acquisition and projection capabilities. Originally intended for military applications, the system could be of interest to the security, emergency response, and future construction markets. The researchers are currently working on an alternative to the monochromatic hologram system implemented for the research demonstrator that would enable full- color images and lower manufacturing costs. bio-artifi cial Contact: [email protected] Zero-energy elevators liver just over the horizon odimas, France’s leading elevator manufacturer, is The EU FP7 d-LIVER project aims to develop a bio- teaming up with Schneider Electric and Grenoble artifi cial liver (BAL) support system for patients S Institute of Technology to develop a smart-grid- connected elevator that is powered both by the grid and suffering from liver failure or awaiting a transplant. by alternative energy sources. The R&D is taking place The project, launched in 2011, brings together under the EU Arrowhead project. CEA-Leti is also involved in the project, supplying a a dozen partners, including CEA-Leti, which is virtual platform to coordinate communication between the elevator’s command-control system and a Schneider supplying sensors for the real-time monitoring of Electric energy optimization module. The system ammonium ions. -

2019 Scientific Report 2019 Scientific Report

TECHNOLOGY RESEARCH INSTITUTE 2019 SCIENTIFIC REPORT 2019 SCIENTIFIC REPORT TECHNOLOGY RESEARCH INSTITUTE LETI 2019 Scientific Report LETI 2019 Scientific Report “CREATIVITY Emmanuel IS INTELLIGENCE Sabonnadière HAVING FUN.” Chief Executive Officer Albert Einstein As one of France’s leading research institutes in the fields of micro and nanoelectronics, CEA-Leti actively supports society’s digital transition—in energy, the environment, and the future of medicine—driven Thomas Ernst by the French Alternative Energies and Atomic Energy VP for Science © Benjamin Zwarts © CEA-Leti Commission (CEA). and Technology he digital transition, which aligns closely with CEA-Leti’s Our last two programs are integrated LiDAR and 5G. They are With the digital revolution well underway, the core expertise, underpins advances in all of these fields, rooted in the cyber-physical systems domain, an area in which use of information technology is expanding faster Tand the institute is running a far-reaching program on we have a long history of early-stage research with our industrial than ever before in fields like transportation, embedded artificial intelligence that will accelerate/boost partners. These technologies are mature, and our R&D is tailored the digital transition. This program is foundational in that it to specific market applications. Here, we leverage the power of telecommunications, healthcare, and augmented will bring the groundbreaking semiconductor technologies our cleanrooms outfitted with the most advanced More-than- reality. The challenge now is to achieve much finer we have developed with our partners over the past several Moore production equipment and the passion for innovation integration. This means inventing new system and years to the forefront. -

An Exoskeleton Controlled by an Epidural Wireless Brain–Machine Interface in a Tetraplegic Patient: a Proof-Of-Concept Demonstration

Articles An exoskeleton controlled by an epidural wireless brain–machine interface in a tetraplegic patient: a proof-of-concept demonstration Alim Louis Benabid, Thomas Costecalde, Andrey Eliseyev, Guillaume Charvet, Alexandre Verney, Serpil Karakas, Michael Foerster, Aurélien Lambert, Boris Morinière, Neil Abroug, Marie-Caroline Schaeffer, Alexandre Moly, Fabien Sauter-Starace, David Ratel, Cecile Moro, Napoleon Torres-Martinez, Lilia Langar, Manuela Oddoux, Mircea Polosan, Stephane Pezzani, Vincent Auboiroux, Tetiana Aksenova, Corinne Mestais, Stephan Chabardes Summary Background Approximately 20% of traumatic cervical spinal cord injuries result in tetraplegia. Neuroprosthetics are Lancet Neurol 2019 being developed to manage this condition and thus improve the lives of patients. We aimed to test the feasibility of a Published Online semi-invasive technique that uses brain signals to drive an exoskeleton. October 3, 2019 https://doi.org/10.1016/ S1474-4422(19)30321-7 Methods We recruited two participants at Clinatec research centre, associated with Grenoble University Hospital, See Online/Comment Grenoble, France, into our ongoing clinical trial. Inclusion criteria were age 18–45 years, stability of neurological https://doi.org/10.1016/ deficits, a need for additional mobility expressed by the patient, ambulatory or hospitalised monitoring, registration S1474-4422(19)30352-7 in the French social security system, and signed informed consent. The exclusion criteria were previous brain CEA, LETI, Clinatec, University surgery, anticoagulant treatments, neuropsychological sequelae, depression, substance dependence or misuse, and of Grenoble, Grenoble, France contraindications to magnetoencephalography (MEG), EEG, or MRI. One participant was excluded because of a (Prof A L Benabid MD, T Costecalde PhD, A Eliseyev PhD, technical problem with the implants. -

Activités Scientifiques, Technologiques Et De

G R E N O B L E I NNOVATION FOR A D V A N C E D N E W T ECHNOLOGIES ACTIVITÉS SCIENTIFIQUES, T E C H N O L O G I Q U E S E T DE VALORISATION 2 GIANT campus d’innovation sur la Presqu’île de Grenoble GIANT aujourd’hui GIANT demain 6 000 chercheurs 10 000 chercheurs 5 000 emplois industriels 7 000 emplois industriels 5 000 étudiants 10 000 étudiants 300 habitants 10 000 habitants 5 000 publications scientifiques par an Investissement 1 300 M€ (2010-2016) 500 brevets prioritaires par an Budget annuel 800 M€ 3 TABLE DES MATIèRES INTRODUCTION 6 1 ACTIVITES SCIENTIFIQUES 9 1.1 CHEMINS DE LA CONNAISSANCE 12 1.1.1 Grands instruments, caractérisation et instrumentation ultime 12 Le Programme Millenium de l’ILL et l’Upgrade Programme de l’ESRF 14 Le Laboratoire National des Champs Magnétiques Intenses (LNCMI) 15 1.1.2 Physique des origines et des infinis 17 1.1.3 Théorie et modélisation 19 1.1.4 Le pôle cryogénique grenoblois 21 1.1.5 Matériaux et procédés 23 1.2 NANOSCIENCES 26 1.2.1 Chimie et électronique du futur 26 Plate-forme Technologique Amont 28 1.2.2 Nanoélectronique 29 Plate-forme Nanofab 31 1.2.3 Nanomagnétisme et électronique de spin 32 1.2.4 Photonique 34 1.3 ÉNERGIES 36 1.3.1 Nouvelles technologies de l’énergie 36 1.3.2 Nucléaire du futur 40 Plate-forme PEREN 41 1.4 SCIENCES DU VIVANT 42 1.4.1 Les protéines : acteurs majeurs du monde vivant 42 1.4.2 Une biologie structurale à dimension européenne 44 1.4.3 Protéines et métaux : recherches à l’interface biologie - chimie 46 1.4.4 Biologie des systèmes intégrés : la protéine dans son -

Grenoble Team Comes Close to Winning Igem

NEWSLETTER Event Innovation Silicon photonics: Leti creates Grenoble two 300-mm testers eti has made a major step forward in the field of optical and electro-optical measurements with L two new testers for photonic components on team comes 300-mm wafers. Until now, there was simply no tester available on the market for wafers of this diameter. Leti made the new devices by replacing the probes on two conventional testers with fiber optics. The probe close to holders are controlled step-by-step using motors and Leti algorithms that automatically align the probes to within a micron. The modified testers underwent several months of testing; the researchers using them are more winning than happy with their performance. Several years ago Leti made similar modifications to 200 mm testers, so the lab now boasts a truly exceptional range of photonic testers, with two 200-mm testers and iGEM two 300-mm testers that are available for use by other research centers. A team of Grenoble students participated in Contact: [email protected] MIT’s prestigious iGEM (International Genetically Engineered Machine) competition in Boston on A high-precision, three-axis November 5–7, 2011. The team didn’t bring home accelerometric signal a trophy this time, but the experience was a eti has designed an addressing electronic circuit memorable one. offering accuracy to within a thousandth of the L full dynamic scale. The circuit’s accuracy was measured in tests conducted by Thales Avionics. While he eleven-member team of mathematics and single-axis sensors commonly offer comparable degrees biology students had been working since of accuracy—especially in aerospace and defense January on a mercury biosensor concept inspired applications—this Leti-designed circuit marks the new T state of the art for three-dimensional signals. -

Grenoble Universite De L'innovation

Ministère de l’Enseignement Supérieur et de la Recherche « Opération Campus » GRENOBLE UNIVERSITE DE L’INNOVATION Note d’intention 29 avril 2008 Grenoble Université de l’Innovation Grenoble Université de l'Innovation Le PRES « Université de Grenoble » (Université Joseph Fourier, Université Pierre Mendès France, Université Stendhal, l’Institut Polytechnique de Grenoble, Institut d’Etudes Politiques) et un collège d’organismes (CEA, CNRS, INRIA, CHU, Cemagref, Grenoble Ecole de Management), avec le partenariat privilégié des grands instruments et laboratoires européens (ESRF, ILL, EMBL) et de l’INSERM, s’engagent à créer « Grenoble Université de l’Innovation » et à l’amener au meilleur niveau mondial. Ils s’appuient sur les atouts internationalement reconnus de l’« écosystème » d’innovation grenoblois, le soutien unanime de l’ensemble des collectivités territoriales, leur relation forte avec le milieu industriel. Ils représentent ensemble 56.000 étudiants, 12.500 chercheurs, enseignants-chercheurs et personnels, 440 brevets par an (au 3ème rang français après Peugeot et Renault), 130 entreprises créées en activité. Dans sa dimension scientifique et éducative comme dans sa dimension urbaine, leur projet est profondément structuré par une exigence de développement durable. Leur ambition est de faire entrer à échéance de dix ans cette nouvelle Université dans les cinquante premières du classement de Shanghai, d’accueillir 5.000 étudiants supplémentaires dont plus de 50% d’étrangers sur ses deux sites, d’attirer des chercheurs de renommée internationale, d’installer des antennes des meilleures universités mondiales à Grenoble et de renforcer sa présence sur les campus étrangers. C’est aussi de construire une université ouverte sur la ville, ayant choisi ses créneaux d’excellence dans un champ éducatif complet et attentive à l’accueil et à l’épanouissement des étudiants comme à leur accès à l’emploi. -

Développement D'interfaces Cerveau Machine Visant À Compenser Les

Développement d’interfaces cerveau machine visant à compenser les déficits moteurs chez des patients tétraplégiques. Etudes expérimentales précliniques Thomas Costecalde To cite this version: Thomas Costecalde. Développement d’interfaces cerveau machine visant à compenser les déficits moteurs chez des patients tétraplégiques. Etudes expérimentales précliniques. Médecine humaine et pathologie. Université de Grenoble, 2012. Français. NNT : 2012GRENS038. tel-00870755 HAL Id: tel-00870755 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-00870755 Submitted on 8 Oct 2013 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. THÈSE Pour obtenir le grade de DOCTEUR DE L’UNIVERSITÉ DE GRENOBLE Spécialité : Biotechnologie, instrumentation, signal et imagerie pour la biologie, la médecine et l’environnement Arrêté ministériel : 7 août 2006 Présentée par Thomas COSTECALDE Thèse dirigée par Stéphan Chabardès préparée au sein du Laboratoire CEA-Leti-Clinatec dans l'École Doctorale « Ingénierie pour la Santé, la Cognition et l’Environnement » Développement d’interfaces cerveau machine